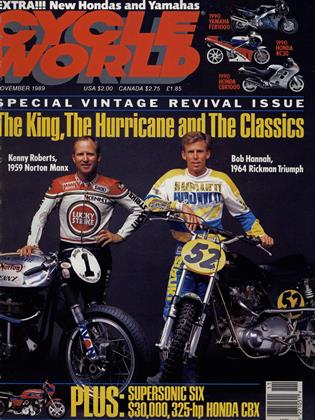

FULL CIRCLE

There’s nothing like riding with an old friend. Just ask Bob Hannah.

RON LAWSON

THE YEAR WAS 1965 AND THE LOCATION WAS THE harsh desert surrounding Lancaster, California. The scene wasn’t very unusual: A father and his 8-year-old son were together with a few friends in the rocky wilderness, all winding down after a good ride. The youngster had parked his Honda 50, and as his dad got off a specially prepared Triumph 650, he turned to the boy and asked casually, “Like to try it?”

That night, the boy’s brief Triumph ride was probably one of those incidents that went unmentioned at the dinner table, a subject better left undiscussed in front of Mom. But when the 8-year-old rode the Triumph that day, he had adapted to it with amazing speed and a surprising lack of effort. As it turned out, that one ride quite probably changed the course of racing history. You see, the father’s name was Bill Hannah, and that was the first time his son Bob had ridden a full-size motorcycle.

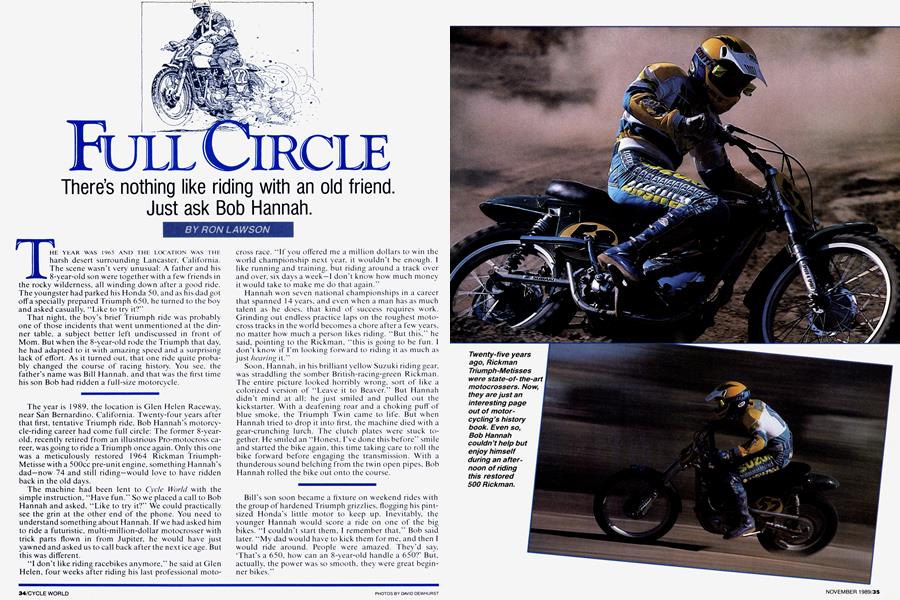

The year is 1989, the location is Glen Helen Raceway, near San Bernardino, California. Twenty-four years after that first, tentative Triumph ride. Bob Hannah’s motorcycle-riding career had come full circle: The former 8-yearold, recently retired from an illustrious Pro-motocross career, was going to ride a Triumph once again. Only this one was a meticulously restored 1964 Rickman TriumphMetisse with a 500cc pre-unit engine, something Hannah's dad—now 74 and still riding—would love to have ridden back in the old days.

The machine had been lent to Cycle World with the simple instruction, “Have fun.” So we placed a call to Bob Hannah and asked, “Like to try it?” We could practically see the grin at the other end of the phone. You need to understand something about Hannah. If we had asked him to ride a futuristic, multi-million-dollar motocrosser with trick parts flown in from Jupiter, he would have just yawned and asked us to call back after the next ice age. But this was different.

“I don’t like riding racebikes anymore,” he said at Glen Helen, four weeks after riding his last professional moto-

cross race. “If you offered me a million dollars to win the world championship next year, it wouldn't be enough. I like running and training, but riding around a track over and over, six days a week —I don't know how much money it would take to make me do that again.”

Hannah won seven national championships in a career that spanned 14 years, and even when a man has as much talent as he does, that kind of success requires work. Grinding out endless practice laps on the roughest motocross tracks in the world becomes a chore after a few years, no matter how much a person likes riding. “But this,” he said, pointing to the Rickman, “this is going to be fun. I don’t know if I'm looking forward to riding it as much as just hearing it.”

Soon, Hannah, in his brilliant yellow Suzuki riding gear, was straddling the somber British-racing-green Rickman. The entire picture looked horribly wrong, sort of like a colorized version of “Leave it to Beaver.” But Hannah didn’t mind at all: he just smiled and pulled out the kickstarter. With a deafening roar and a choking puff of blue smoke, the Triumph Twin came to life. But when Hannah tried to drop it into first, the machine died with a gear-crunching lurch. The clutch plates were stuck together. He smiled an “Honest, I’ve done this before” smile and started the bike again, this time taking care to roll the bike forward before engaging the transmission. With a thunderous sound belching from the twin open pipes. Bob Hannah rolled the bike out onto the course.

Bill's son soon became a fixture on weekend rides with the group of hardened Triumph grizzlies, flogging his pintsized Honda’s little motor to keep up. Inevitably, the younger Hannah would score a ride on one of the big bikes. “I couldn’t start them. I remember that,” Bob said later. “My dad would have to kick them for me, and then I would ride around. People were amazed. They’d say, ‘That’s a 650, how can an 8-year-old handle a 650?' But, actually, the power was so smooth, they were great beginner bikes.”

The Triumph rides whetted Hannah’s appetite for larger motorcycles. The little Honda gave way to a Hodaka 90, then to a Hodaka 100 and eventually to a Yamaha AT 1. No matter what Hannah started a desert outing on, though, a Triumph ride usually highlighted the agenda.

After experimenting with a few turns on Glen Helen’s sun-baked ATV course, Hannah came back with an uncertain look on his face. He was having a difficult time aligning this particular Triumph with the one in his memories. “I forgot how doggy these things ran. It doesn’t really have a powerband, you rev it and it just makes more noise.” He shook his head. “It really gives you respect for the guys who rode these things. I could show you some hills they climbed that most guys wouldn’t go up today,” he said. He looked down at his left leg, which was covered in oil from the Triumph’s leaky rockerarm covers, and said, “My dad’s did this, too, but he fixed it somehow.” He searched his memory for a few moments and started the bike again.

At one point in the day, Matt Hilgenberg, the Rickman’s owner, showed up just to watch. Hannah, who had been getting looser and looser on the machine, suddenly looked like a kid whose parents just found him on the couch with the baby sitter. After all, when someone owns a bike as nicely restored as the Rickman, you would expect him to cringe every time the bike revved past 1000 rpm. But Hilgenberg isn’t like that. He built the bike to be ridden and raced, and he seemed to like the idea that Hannah was extracting the most from the machine. The exchange between Hannah and Hilgenberg was interesting.

Hannah: “How high do you normally rev this thing?”

Hilgenberg: “It depends on how high the guy on the one next to you is revving his. Whatever it takes to beat him to the next turn.”

Hannah: “It works really good in rough terrain, but it’s a shame to beat it up.”

Hilgenberg: “No, go ahead. You can actually clear some double jumps on it.”

Hannah: “Maybe you can clear double jumps onit.

Hilgenberg: “It jumps just fine. It just doesn’t land too good.”

Hannah quickly realized that he was on a racebike. This was no museum piece that he had to baby around the course. Before long, he was slamming the bike through turns and screaming the engine as high as it would go, all while Hilgenberg watched and smiled. It was clear that Hannah, too, was having fun.

“It would take about two days to really learn how to ride it,” Hannah said after a session of third-gear, feetup slides that would make Scott Parker jealous. “You just have to think about two seconds ahead and get on the gas early. It handles better in a slide than it does going straight. It feels weird—sometimes I couldn’t tell if it was tracking straight or if the front end was going away. But it never did anything bad all day.”

The bike and the rider had finally come to terms. Hannah looked at the machine with rediscovered respect as it was being loaded into the back of Hilgenberg’s van. “They could learn something from this bike today. I’d like to take it to Suzuki and tell them to make their tank this narrow,” he said, looking at the Rickman’s skinny fuel tank.

Hannah climbed out of his bright yellow riding gear as the dull green, and now oil-splattered, Triumph was hauled away. He smiled and spoke slowly. “I’d much rather ride that than my racebike,” he said. “It sounds better.”

And then he was quiet for a minute or so. “I just wish my dad was here.”

Hannah didn’t ride with his dad’s group as much when he got older. There were lighter, faster machines to be ridden, and soon Bob had a CZ, on which he was instantly proficient. “I never even started racing until I was almost 18. I bought a 1975 Husky 250 and won my first race,” Hannah recalled. A little over one year later, he won the I25cc national championship for Yamaha. To the rest of the world at the time, it seemed like the teenager had come out of nowhere, complete with the talent to be a champion. But Bill Hannah and a certain handful of Triumph riders knew that Bob’s ability was no miracle. It was the result of all those weekends in the desert and a father who didn’t mind giving his son a little freedom.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

November 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

November 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

November 1989 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

November 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Update: Spicy News From Across the Sea

November 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha Rings In the New Year

November 1989 By Camron E. Bussard