UP FRONT

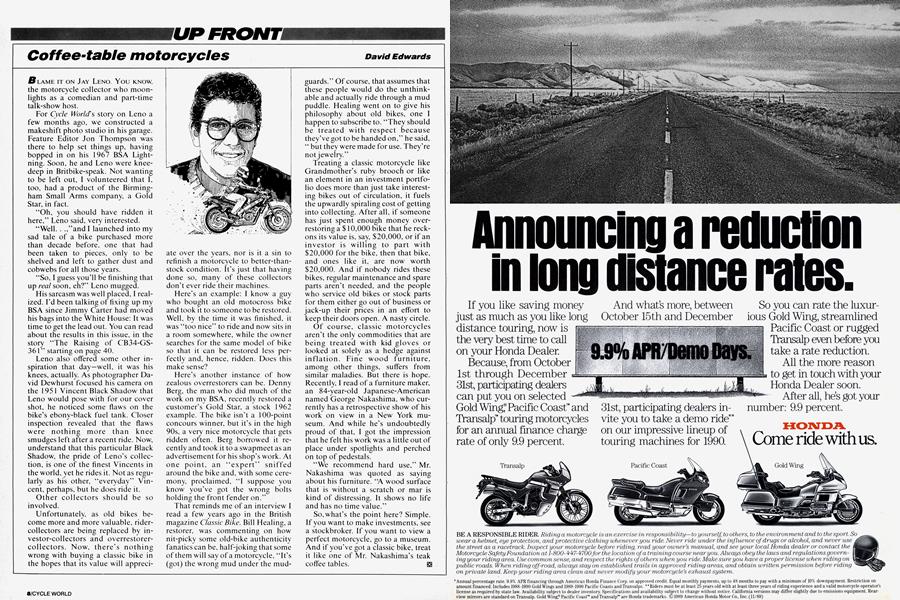

Coffee-table motorcycles

David Edwards

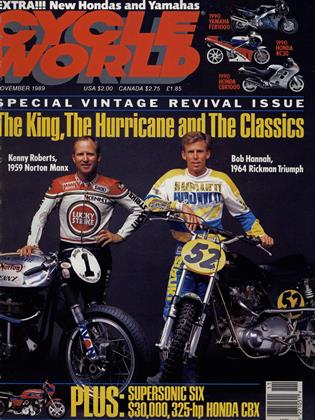

BLAME IT ON JAY LENO. YOU KNOW, the motorcycle collector who moon-lights as a comedian and part-time talk-show host.

For Cycle World's story on Leno a few months ago, we constructed a makeshift photo studio in his garage. Feature Editor Jon Thompson was there to help set things up, having bopped in on his 1967 BSA Lightning. Soon, he and Leno were knee-deep in Britbike-speak. Not wanting to be left out, I volunteered that I, too, had a product of the Birmingham Small Arms company, a Gold Star, in fact.

“Oh, you should have ridden it here,” Leno said, very interested.

“Well. . .,”and I launched into my sad tale of a bike purchased more than decade before, one that had been taken to pieces, only to be shelved and left to gather dust and cobwebs for all those years.

“So, I guess you’ll be finishing that up real soon, eh?” Leno mugged.

His sarcasm was well placed, I realized. Ed been talking of fixing up my BSA since Jimmy Carter had moved his bags into the White House: It was time to get the lead out. You can read about the results in this issue, in the story “The Raising of CB34-GS36 1 ” starting on page 40.

Leno also offered some other inspiration that day—well, it was his knees, actually. As photographer David Dewhurst focused his camera on the 1951 Vincent Black Shadow that Leno would pose with for our cover shot, he noticed some flaws on the bike’s ebony-black fuel tank. Closer inspection revealed that the flaws were nothing more than knee smudges left after a recent ride. Now, understand that this particular Black Shadow, the pride of Leno’s collection, is one of the finest Vincents in the world, yet he rides it. Not as regularly as his other, “everyday” Vincent, perhaps, but he does ride it.

Other collectors should be so involved.

Unfortunately, as old bikes become more and more valuable, ridercollectors are being replaced by investor-collectors and overrestorercollectors. Now, there’s nothing wrong with buying a classic bike in the hopes that its value will appreciate over the years, nor is it a sin to refinish a motorcycle to better-thanstock condition. It’s just that having done so, many of these collectors don't ever ride their machines.

Here’s an example: I know a guy who bought an old motocross bike and took it to someone to be restored. Well, by the time it was finished, it was “too nice” to ride and now sits in a room somewhere, while the owner searches for the same model of bike so that it can be restored less perfectly and, hence, ridden. Does this make sense?

Here's another instance of how zealous overrestorers can be. Denny Berg, the man who did much of the work on my BSA, recently restored a customer’s Gold Star, a stock 1962 example. The bike isn’t a 100-point concours winner, but it’s in the high 90s, a very nice motorcycle that gets ridden often. Berg borrowed it recently and took it to a swapmeet as an advertisement for his shop's work. At one point, an “expert” sniffed around the bike and, with some ceremony, proclaimed, “I suppose you know you’ve got the wrong bolts holding the front fender on.”

That reminds me of an interview I read a few years ago in the British magazine Classic Bike. Bill Healing, a restorer, was commenting on how nit-picky some old-bike authenticity fanatics can be, half-joking that some of them will say of a motorcycle, “It’s (got) the wrong mud under the mudguards.” Of course, that assumes that these people would do the unthinkable and actually ride through a mud puddle. Healing went on to give his philosophy about old bikes, one I happen to subscribe to. “They should be treated with respect because they’ve got to be handed on,” he said, “ but they were made for use. They’re not jewelry.”

Treating a classic motorcycle like Grandmother’s ruby brooch or like an element in an investment portfolio does more than just take interesting bikes out of circulation, it fuels the upwardly spiraling cost of getting into collecting. After all, if someone has just spent enough money overrestoring a $ 10,000 bike that he reckons its value is, say, $20,000, or if an investor is willing to part with $20,000 for the bike, then that bike, and ones like it, are now worth $20,000. And if nobody rides these bikes, regular maintenance and spare parts aren’t needed, and the people who service old bikes or stock parts for them either go out of business or jack-up their prices in an effort to keep their doors open. A nasty circle.

Of course, classic motorcycles aren’t the only commodities that are being treated with kid gloves or looked at solely as a hedge against inflation. Fine wood furniture, among other things, suffers from similar maladies. But there is hope. Recently, I read of a furniture maker, an 84-year-old Japanese-American named George Nakashima, who currently has a retrospective show of his work on view in a New York museum. And while he’s undoubtedly proud of that, I got the impression that he felt his work was a little out of place under spotlights and perched on top of pedestals.

“We recommend hard use,” Mr. Nakashima was quoted as saying about his furniture. “A wood surface that is without a scratch or mar is kind of distressing. It shows no life and has no time value.”

So,what’s the point here? Simple. If you want to make investments, see a stockbroker. If you want to view a perfect motorcycle, go to a museum. And if you’ve got a classic bike, treat it like one of Mr. Nakashima’s teak coffee tables.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

November 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

November 1989 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

November 1989 -

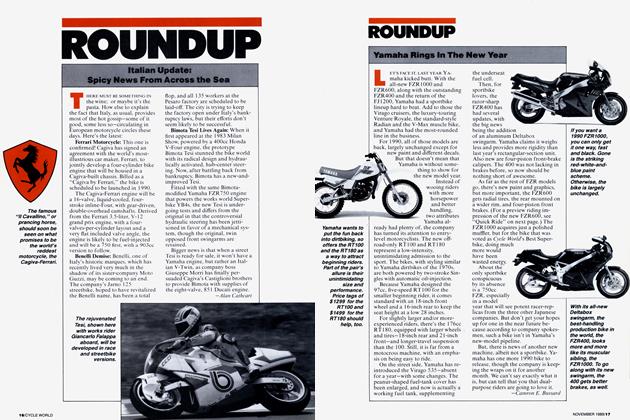

Roundup

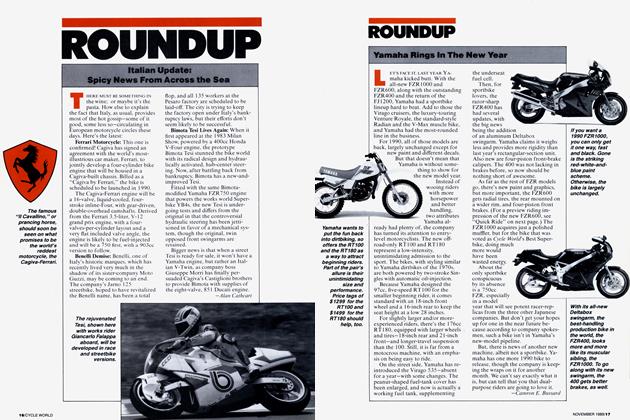

RoundupItalian Update: Spicy News From Across the Sea

November 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

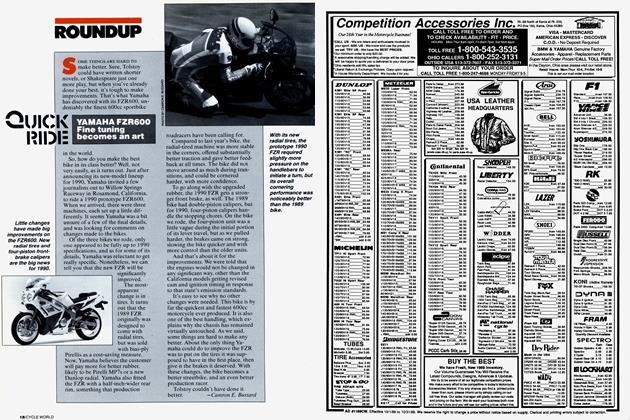

RoundupYamaha Rings In the New Year

November 1989 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

November 1989 By Camron E. Bussard