TDC

Counting sheep

Kevin Cameron

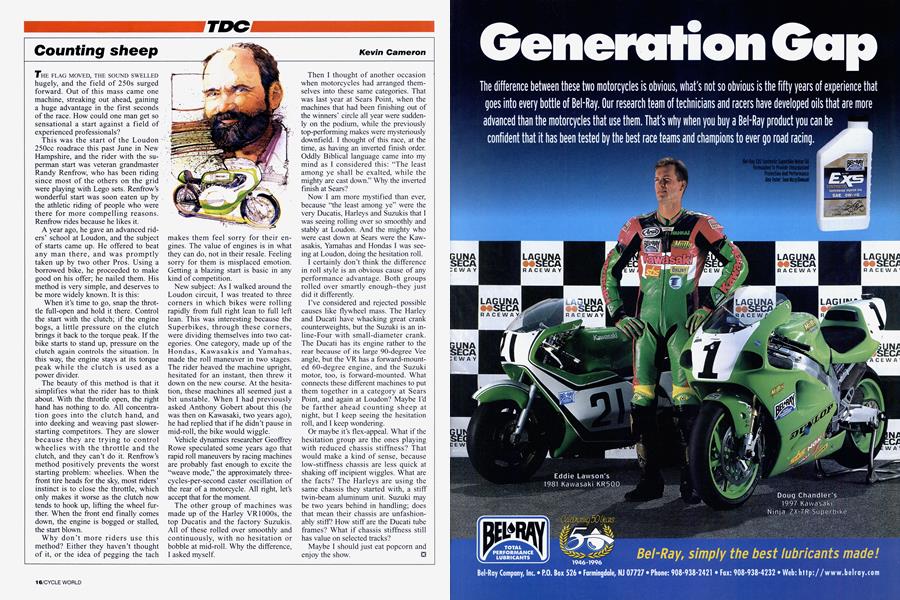

THE FLAG MOVED, THE SOUND SWELLED hugely, and the field of 250s surged forward. Out of this mass came one machine, streaking out ahead, gaining a huge advantage in the first seconds of the race. How could one man get so sensational a start against a field of experienced professionals?

This was the start of the Loudon 250cc roadrace this past June in New Hampshire, and the rider with the superman start was veteran grandmaster Randy Renfrow, who has been riding since most of the others on the grid were playing with Lego sets. Renfrew’s wonderful start was soon eaten up by the athletic riding of people who were there for more compelling reasons. Renfrow rides because he likes it.

A year ago, he gave an advanced riders’ school at Loudon, and the subject of starts came up. He offered to beat any man there, and was promptly taken up by two other Pros. Using a borrowed bike, he proceeded to make good on his offer; he nailed them. His method is very simple, and deserves to be more widely known. It is this:

When it’s time to go, snap the throttle full-open and hold it there. Control the start with the clutch; if the engine bogs, a little pressure on the clutch brings it back to the torque peak. If the bike starts to stand up, pressure on the clutch again controls the situation. In this way, the engine stays at its torque peak while the clutch is used as a power divider.

The beauty of this method is that it simplifies what the rider has to think about. With the throttle open, the right hand has nothing to do. All concentration goes into the clutch hand, and into deeking and weaving past slowerstarting competitors. They are slower because they are trying to control wheelies with the throttle and the clutch, and they can’t do it. Renfrew’s method positively prevents the worst starting problem: wheelies. When the front tire heads for the sky, most riders’ instinct is to close the throttle, which only makes it worse as the clutch now tends to hook up, lifting the wheel further. When the front end finally comes down, the engine is bogged or stalled, the start blown.

Why don’t more riders use this method? Either they haven’t thought of it, or the idea of pegging the tach makes them feel sorry for their engines. The value of engines is in what they can do, not in their resale. Feeling sorry for them is misplaced emotion. Getting a blazing start is basic in any kind of competition.

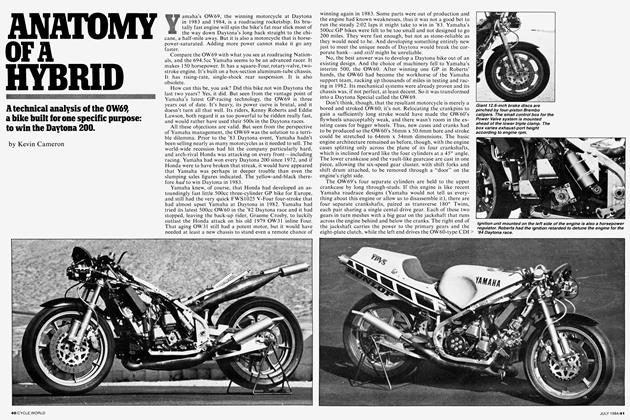

New subject: As I walked around the Loudon circuit, I was treated to three corners in which bikes were rolling rapidly from full right lean to full left lean. This was interesting because the Superbikes, through these corners, were dividing themselves into two categories. One category, made up of the Hondas, Kawasakis and Yamahas, made the roll maneuver in two stages. The rider heaved the machine upright, hesitated for an instant, then threw it down on the new course. At the hesitation, these machines all seemed just a bit unstable. When I had previously asked Anthony Gobert about this (he was then on Kawasaki, two years ago), he had replied that if he didn’t pause in mid-roll, the bike would wiggle.

Vehicle dynamics researcher Geoffrey Rowe speculated some years ago that rapid roll maneuvers by racing machines are probably fast enough to excite the “weave mode,” the approximately threecycles-per-second caster oscillation of the rear of a motorcycle. All right, let’s accept that for the moment.

The other group of machines was made up of the Harley VR 1000s, the top Ducatis and the factory Suzukis. All of these rolled over smoothly and continuously, with no hesitation or bobble at mid-roll. Why the difference, I asked myself.

Then I thought of another occasion when motorcycles had arranged themselves into these same categories. That was last year at Sears Point, when the machines that had been finishing out of the winners’ circle all year were suddenly on the podium, while the previously top-performing makes were mysteriously downfield. I thought of this race, at the time, as having an inverted finish order. Oddly Biblical language came into my mind as I considered this: “The least among ye shall be exalted, while the mighty are cast down.” Why the inverted finish at Sears?

Now I am more mystified than ever, because “the least among ye” were the very Ducatis, Harleys and Suzukis that I was seeing rolling over so smoothly and stably at Loudon. And the mighty who were cast down at Sears were the Kawasakis, Yamahas and Hondas I was seeing at Loudon, doing the hesitation roll.

I certainly don’t think the difference in roll style is an obvious cause of any performance advantage. Both groups rolled over smartly enough-they just did it differently.

I’ve considered and rejected possible causes like flywheel mass. The Harley and Ducati have whacking great crank counterweights, but the Suzuki is an inline-Four with small-diameter crank. The Ducati has its engine rather to the rear because of its large 90-degree Vee angle, but the VR has a forward-mounted 60-degree engine, and the Suzuki motor, too, is forward-mounted. What connects these different machines to put them together in a category at Sears Point, and again at Loudon? Maybe I’d be farther ahead counting sheep at night, but I keep seeing the hesitation roll, and I keep wondering.

Or maybe it’s flex-appeal. What if the hesitation group are the ones playing with reduced chassis stiffness? That would make a kind of sense, because low-stiffness chassis are less quick at shaking off incipient wiggles. What are the facts? The Harleys are using the same chassis they started with, a stiff twin-beam aluminum unit. Suzuki may be two years behind in handling; does that mean their chassis are unfashionably stiff? How stiff are the Ducati tube frames? What if chassis stiffness still has value on selected tracks?

Maybe I should just eat popcorn and enjoy the show. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue