Back to the Future

Before there was Duolever, there was Norman Hossack

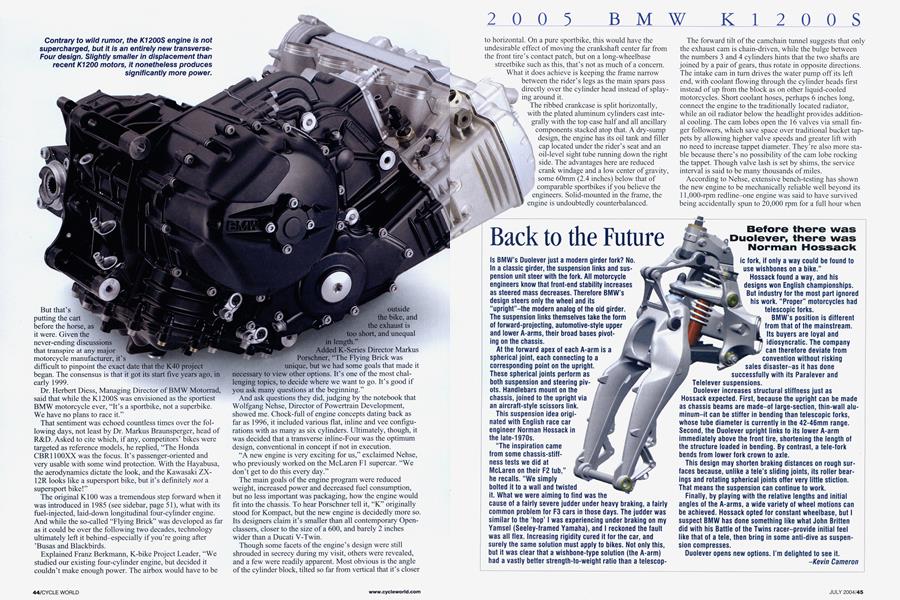

Is BMW’s Duolever just a modern girder fork? No.

In a classic girder, the suspension links and suspension unit steer with the fork. All motorcycle engineers know that front-end stability increases as steered mass decreases. Therefore BMW’s design steers only the wheel and its “upright”—the modern analog of the old girder.

The suspension links themselves take the form of forward-projecting, automotive-style upper and lower A-arms, their broad bases pivoting on the chassis.

At the forward apex of each A-arm is a spherical joint, each connecting to a corresponding point on the upright These spherical joints perform as both suspension and steering pivots. Handlebars mount on the chassis, joined to the upright via an aircraft-style scissors link.

This suspension idea originated with English race car engineer Norman Hossack in the late-1970s.

“The inspiration came from some chassis-stiffness tests we did at McLaren on their F2 tub,” he recalls. “We simply bolted it to a wall and twisted it. What we were aiming to find was the cause of a fairly severe judder under heavy braking, a fairly common problem for F3 cars in those days. The judder was similar to the ‘hop’ I was experiencing under braking on my Yamsel (Seeley-framed Yamaha), and I reckoned the fault was all flex. Increasing rigidity cured it for the car, and surely the same solution must apply to bikes. Not only this, but it was clear that a wishbone-type solution (the A-arm) had a vastly better strength-to-weight ratio than a telescopic fork, if only a way could be found to use wishbones on a bike.”

Hossack found a way, and his designs won English championships. But industry for the most part ignored his work. “Proper” motorcycles had telescopic forks.

BMW’s position is different from that of the mainstream. Its buyers are loyal and idiosyncratic. The company can therefore deviate from convention without risking sales disaster-as it has done successfully with its Paralever and Telelever suspensions.

Duolever increases structural stiffness just as Hossack expected. First, because the upright can be made as chassis beams are made-of large-section, thin-wall aluminum—it can be stiffer in bending than telescopic forks, whose tube diameter is currently in the 42-46mm range. Second, the Duolever upright links to its lower A-arm immediately above the front tire, shortening the length of the structure loaded in bending. By contrast, a tele-fork bends from lower fork crown to axle.

This design may shorten braking distances on rough surfaces because, unlike a tele’s sliding joints, its roller bearings and rotating spherical joints offer very little stiction. That means the suspension can continue to work.

Finally, by playing with the relative lengths and initial angles of the A-arms, a wide variety of wheel motions can be achieved. Hossack opted for constant wheelbase, but I suspect BMW has done something like what John Britten did with his Battle of the Twins racer-provide initial feel like that of a tele, then bring in some anti-dive as suspension compresses.

Duolever opens new options. I’m delighted to see it.

Kevin Cameron