600 SUPERSPORT

RACE WATCH

Call it the Supersupport class

DAIN GINGERELLI

RON LAWSON

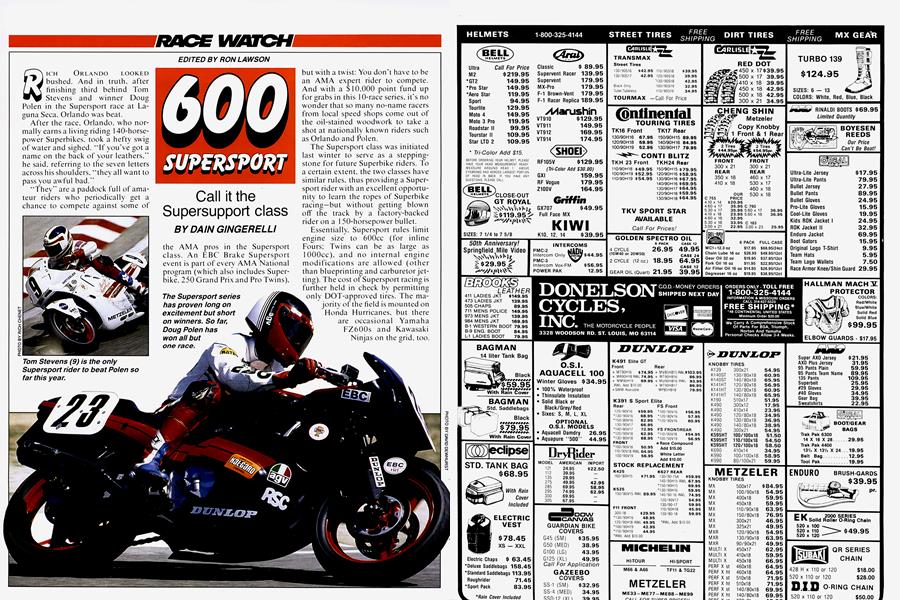

RICH ORLANDO LOOKED bushed. And in truth, after finishing third behind Tom Stevens and winner Doug Polen in the Supersport race at Laguna Seca, Orlando was beat.

After the race, Orlando, who normally earns a living riding 140-horsepower Superbikes, took a hefty swig of water and sighed. “If you've got a name on the back of your leathers,” he said, referring to the seven letters across his shoulders, “they all want to pass you awful bad.”

“They” are a paddock full of amateur riders who periodically get a chance to compete against some of

the AMA pros in the Supersupport class. An EBC Brake Supersport event is part of every AMA National program (which also includes Superbike. 250 Grand Prix and Pro Tw ins).

but with a twist: You don't have to be an AMA expert rider to compete. And with a $10.000 point fund up for grabs in this 10-race series, it's no wonder that so many no-name racers from local speed shops come out of the oil-stained woodwork to take a shot at nationally known riders such as Orlando and Polen.

The Supersport class was initiated last winter to serve as a steppingstone for future Superbike riders. To a certain extent, the two classes have similar rules, thus providing a Supersport rider with an excellent opportunity to learn the ropes of Superbike racing—but without getting blown off the track by a factory-backed rider on a 1 50-horsepower bullet.

Essentially, Supersport rules limit engine size to 600cc (for inline Fours; Twins can be as large as lOOOcc). and no internal engine modifications are allowed (other than blueprinting and carburetor jetting). The cost of Supersport racing is further held in check by permitting only DOT-approved tires. The majority of the field is mounted on Honda Hurricanes, but there are occasional Yamaha FZ600s and Kawasaki Ninjas on the grid, too. As a box-stock-based class, the Supersport Series promotes close competition—with the exception of one rider (whose initials are Doug Polen). Even polished pros such as Orlando, who had to fight and claw his way to third at Laguna Seca, will attest to the competitive nature of the class. As he said after the race, “It got hectic out there, with everybody slamming into one another and getting crazy.”

The Laguna Supersport race especially made the no-names go crazy. Laguna Seca is the roadrace of the year, because all the industry’s movers and shakers are on the sidelines, basking in the Monterey sun while watching the action on the track— and searching for future stars. It was at Laguna where Lreddie Spencer permanently etched his name in the sport eight years ago by winning the Superbike race for Kawasaki; and it was at the Monterey, California, track where a young, unseasoned Kevin Schwantz got his start with Yoshimura-Suzuki a couple of years ago. And it was at Laguna Seca where

several dozen West Coast hopefuls set up camp this year, preparing for the Supersport race on Saturday.

Unfortunately for the Golden State no-names, a certain “name” rider from Texas—Polen—entered his Honda Hurricane in the same race. It was the same Darth Vader-black bike on which he had won four of the five previous EBC races. Obviously, earning a name would be a tough assignment for local riders at Laguna Seca this year.

One of those local “shoes” was Richard Moore, riding for Dennis Smith’s Torrance, California-based Vance & Hines speed shop. Having won a bundle of trophies (not to mention a pile of dollars that Honda has paid to winning Hurricanemounted riders in club racing) at Willow Springs races this year, Moore and his black Hurricane set his sights on Polen.

But Moore and Smith were still recuperating from a bad experience with Polen the previous week during a club race at Willow, where Moore played second-fiddle to the intruder

from Texas. Thursday’s unofficial practice at Laguna Seca only confirmed Smith's worst fears. And by late Thursday afternoon, Smith forecast a good race, “If Polen doesn’t walk away with it.”

As it was, Polen was circulating the 1.9-mile course with lap times just two seconds shy of his Superbike times. Of Polen, Smith said, “He’s worth another 10 horsepower just by being on the bike.” Another competitor complained that it would take lap times of 1:12 to win the Supersport race. He was almost right. On his way to the win, Polen dipped into the 1:11 bracket. By comparison, the fastest Superbike times hovered in the 1:08 range.

Whether or not Polen’s right wrist is worth an additional 10 horsepower is pure speculation on Smith’s part. But he does know the numbers that Moore’s Vance & Hines 600 generates on the dyno. “Eighty-four,” boasts his tuner, Bill Loster. Impressive figures, until Loster laments, “But we hear through the grapevine that Polen's bike has 89.” Another source suggests 92, which, using Smith’s formula, translates into Polen having more than 100 horsepower during the race.

Talking with Polen, though, you get the impression that his bike is just another Hurricane 600—a bike that any no-name can buy at the shop, and after giving it a little pre-race prep, chase the checkered flag. “I haven’t touched that engine since Daytona,” he claims. Maybe so, but he didn’t mention anything about the work habits of his brothers, James and Greg, who oversee the maintenance and tuning.

Polen may have stretched the truth about his bike being your average, run-of-the-mill Hurricane, too. Fact is, Honda loaned him the bike for the year. And according to sources within Honda’s Gardena, California, complex, Polen’s 598cc (the .020inch legal overbore notwithstanding) ball of fire isn’t exactly like what rolls off the showroom floor. The Gardena contact says the bike is Supersport-legal, but isn’t representative of a typical dealer-ready Hon-

da Hurricane.

Beyond several internal legal tweaks, Polen’s Hurricane differs from others at the exhaust pipe. The pipe is registered as an HRC (Honda Racing Center) system, and is within the required 1 15-decibel limit. In reality, according to Polen, the system is nothing more than a stock Hurricane pipe with the flat disc-baffle removed. “It gives better mid-range power,” he claims, “and takes nothing away from the top.”

Despite Polen’s candor, people in the Laguna Seca paddock wanted a look-see inside his engine. And he was more than happy to oblige—after the race. The same race in which he had to start from the back of the grid because an ignition wire had come loose during his qualifying heat, forcing him to DNF on the first lap. But after dusting the competition in the Main, winning by nearly 15 seconds, he said in the press room, “They want to see everything in that engine. Roger (Edmonston, AMA’s roadrace manager) has been getting all kinds of calls, so they’ve decided to tear it all

the way down here.”

The eternal optimist, Polen looked on the brighter side of the mandatory teardown. “Have at it,” he said, “It’ll give me a chance to freshen it up.” After all, an engine can get mighty tired after winning five of six races.

Polen won the post-race teardown, too, and the world was once again made safe. But not for the no-names, led by young Tom Stevens, of Florida. For a rookie racer (on the National cicuit, that is), Stevens has had what could be considered a successful year. He’s the only rider to defeat Polen so far this year (winning at Road Atlanta), and was second-fastest all weekend at Laguna Seca. And he’s hungry. Hungry enough that Team Suzuki has signed him to ride their championship GSX-R1100 in the WERA Endurance Series the remainder of the season.

But it’s in the Supersport series where Stevens wants to concentrate his efforts. “I’m learning the tracks for next year,” he insists. Okay, but for what next year? “Superbike. I’ll have ridden all the National tracks in Supersport, so when I ride Superbike next year. I’ll know when to turn left and right.”

Considering that the AMA is discussing downsizing America’s premier roadrace class from the current 750cc limit to 600cc, Stevens’ roadracing career could parallel Superbike’s future. While such a rule wouldn't be instituted until 1990, Superbike riders could make good

use of the EBC Series to acquaint themselves with the smaller bikes.

It’s time, then, that the AMA and American roadrace fans took a closer look at the small-bore classes—especially since Superbike racing so far this year has been anything but super. The highlight for the thundering Superbikes this year has been the dubious ability to transform expensive race gas into cheap noise. On the

other hand, the less costly 600s have been responsible for some very exciting, high-class racing. And it’s time the AMA and fans realize that.

So when the AMA circus comes to town, don’t be surprised if the crowds shy away from the big top. After all, *the best show is in the support classes, particularly the 600 Supersport race. And it’s getting better.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialOh, Why, Tell Me Why

October 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeSherlock And the Golden Hour

October 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1987 -

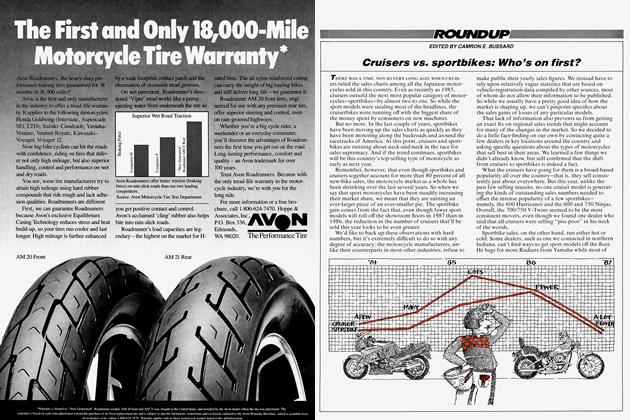

Roundup

RoundupCruisers Vs. Sportbikes: Who's On First?

October 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Sdr Rocket

October 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia's Expansion Plans

October 1987 By Alan Cathcart