Sherlock and the golden hour

AT LARGE

WHEN YOU LOOK AT A WRECKED motorcycle, what do you see? Most of us just see a mess. Twisted pipes, broken levers, bent pegs, tweaked handlebars, bashed tanks, ragged fiberglass. So much junk whose only story is one of misfortune.

Not so Jim Adams, 34-year-old former flat-track racer, motocrosser and trials rider from Webster, Pennsylvania. Adams believes that a wrecked bike can mean the difference between life and death, at least if the person viewing it is in the lifeor-death business—which Adams is in. As Jim Adams, paramedic. And paramedic instructor.

According to Adams, although the Emergency Medical Services community in America is doing a fine job, there are some gaps in the curriculum of the Emergency Medical Technicians who come to our aid when we go down on road or track. That’s where the wrecked bikes and the golden hour come in.

When you crash, your golden hour begins. According to statistics, that’s the hour you have in which to be given correct first aid. have your major traumas diagnosed and be taken to a trauma center for treatment. Obviously, it’s important that as few as possible of your golden minutes be wasted. Hence Jim Adams' course called, “Motorcycle Trauma—Mechanisms of Injury.”

Before listening to Adams, I had never thought about the specific training given to paramedics concerning motorcycle accidents. I assumed—wrongly, according to him— that because motorcycle crashes were quite common occurrences, the catalog of bike-related injuries and their causes would be well-established in the Emergency Medical Services world. But his experience, beginning in 1978, was that such was not the case. He found that his colleagues who were not riders themselves tended to approach each accident as a unique event, and were therefore using up more time than was necessary simply to establish what might be wrong with the victim. So he set about correcting that. And since 1981, Adams has been teaching his course to paramedics and doctors, to date having registered more than

7300 students.

Along the way, he developed a method of damage evaluation he calls the “primary survey,” along with a new helmet-removal technique and some strong opinions about what the EMS community and the motorcycle world can do to stretch the golden hour we all hope we won’t need.

Sherlock Holmes would approve of Adams’ survey, since it involves the same combination of observation and deduction that made the fictional sleuth so famous. Using his own Honda Ascot, Adams teaches his students first to understand the bike’s systems and components—of which most students, he says, have no previous knowledge.

This allows them to understand the second phase, which occurs at the accident site: observation of the dynamics of the accident. He teaches the EMTs how to use “the walk from the ambulance to the victim” to evaluate what happened. He shows them the kinds of accidents bikes have, and how they occur.

Then comes the most critical part: the examination of the bike itself, even before the victim. “The crashed bike can almost always tell you what happened to the rider,” claims Adams. and he begins detailing the evidence. from bent handlebars (broken femurs) to bashed gas tanks (broken pelvis), snapped levers (broken wrists), bent pegs (broken ankles) and so on, piece by piece. “The object is to allow the EMT to look at the bike on the way to the victim and

have some idea what to look for to save time,” he concludes.

Adams believes he is alone in teaching the peculiarities of motorcycle accidents and traumas to the EMS world. This means his courses are “sold” by word of mouth, and, inevitably, that his ideas sometimes clash with current doctrine.

The matter of helmet removal is one such idea. Adams says that the “approved” method requires one person to steady the head and helmet of the victim with a “bridge” of hands on the chest and back. He argues that this can actually aggravate affairs if the EMTs are hurried, since the chest-bracing hand can inadvertently block the victim’s airway. He advocates a side-bridge instead.

Adams also believes that all of the helmet manufacturers ought to provide clavicle cutouts on their fullface helmets and give their purchasers standard-format stickers on which the buyer would note his name, social security number, blood type, allergies and medical problems. Street riders should be as earnest in using these stickers as racers are, he says, and also ought to acquaint themselves with the ABCs of first aid, as well as how to remove—correctly—a crash victim’s helmet.

As to what else riders can do, Adams notes that, since his experience and the research he’s read tells him that the majority of street riders who crash badly enough to need him are neophytes, and since drugs and alcohol seem overwhelmingly involved in their crashes, the obvious things are: Don’t drink and ride, and work hard at learning how to be a better rider. Asked how a novice can do that, he grins and says, “Go trials riding.”

I figured he wanted novices to do trials for the finesse. Wrong again. He wants people to ride trials to learn how and when to get off. “When I ride eight hours of trials,” he says, “I fall down a hundred times, and I learn something each time.”

If Jim Adams weren’t a two-time AMA District 5 trials champion as well as a respected teacher and paramedic, his words might be lightly taken. But he is, so they shouldn't be. By neophytes or anyone else.

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialOh, Why, Tell Me Why

October 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1987 -

Roundup

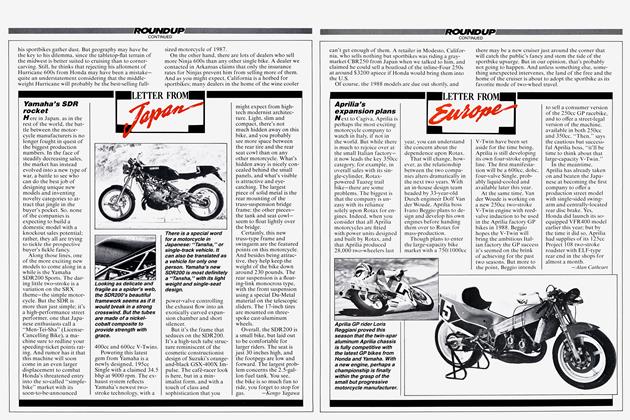

RoundupCruisers Vs. Sportbikes: Who's On First?

October 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Sdr Rocket

October 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia's Expansion Plans

October 1987 By Alan Cathcart -

Rounup

RounupFlying M Ranch

October 1987 By Ron Lawson