Battle of the Talking Tees

AT LARGE

YOU CAN LEARN A LOT FROM TEE shirts. There is, of course, the message itself, which sometimes is worthy of contemplation (“He who dies with the most toys wins the game”), sometimes of amusement (“If you don’t ride a [fill in the name of your favorite bike], you ain’t [fill in the appropriate biological waste product]”), and sometimes only of puzzlement. Into the latter category fell the sudden spate of Harvard tee shirts that erupted on the middle-aged bodies of the guys who frequent the oxymoronically labeled health club to which I trudge three times a week.

What puzzled me was not that these guys had gone to Harvard, but that, 20 years or more after doing so, they felt compelled to broadcast the fact at a place where sweat is supposed to be the only currency of value. And soonthere appeared new shirts with other colleges and universities advertised: Brown, Princeton, Yale, the whole Ivy League.

Naturally, there was only one appropriate response,and it wouldnot be an ad for my alma mater, the University of California. No, it had to be special. It had to be about bikes.

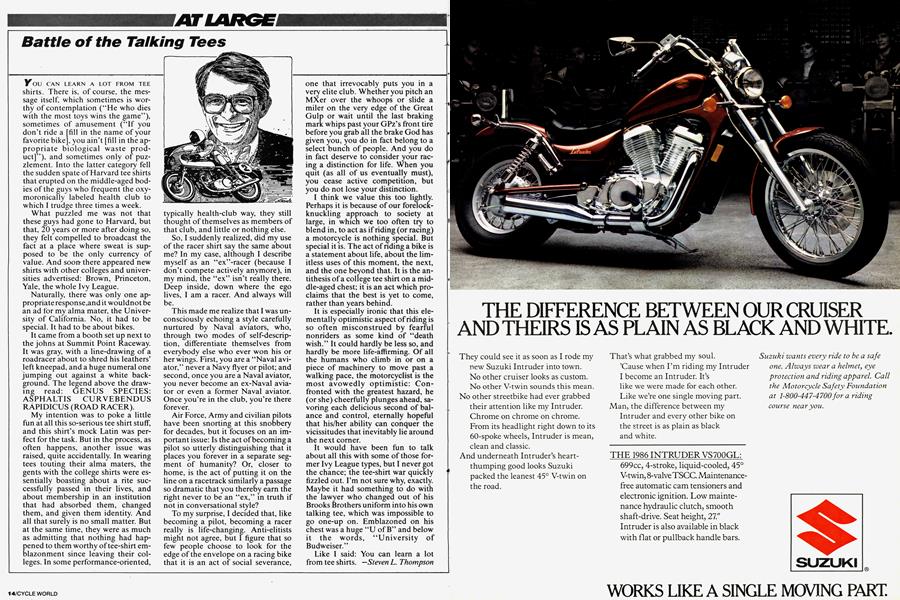

It came from a booth set up next to the johns at Summit Point Raceway. It was gray, with a line-drawing of a roadracer about to shred his leathers’ left kneepad, and a huge numeral one jumping out against a white background. The legend above the drawing read: GENUS SPECIES:

ASPHALTIS CURVEBENDUS RÁPIDICUS (ROAD RACER).

My intention was to poke a little fun at all this so-serious tee shirt stuff, and this shirt’s mock Latin was perfect for the task. But in the process, as often happens, another issue was raised, quite accidentally. In wearing tees touting their alma maters, the gents with the college shirts were essentially boasting about a rite successfully passed in their lives, and about membership in an institution that had absorbed them, changed them, and given them identity. And all that surely is no small matter. But at the same time, they were as much as admitting that nothing had happened to them worthy of tee-shirt emblazonment since leaving their colleges. In some performance-oriented, typically health-club way, they still thought of themselves as members of that club, and little or nothing else.

So, I suddenly realized, did my use of the racer shirt say the same about me? In my case, although I describe myself as an “ex”-racer (because I don’t compete actively anymore), in my mind, the “ex” isn’t really there. Deep inside, down where the ego lives, I am a racer. And always will be.

This made me realize that I was unconsciously echoing a style carefully nurtured by Naval aviators, who, through two modes of self-description, differentiate themselves from everybody else who ever won his or her wings. First, you are a “Naval aviator,” never a Navy flyer or pilot; and second, once you are a Naval aviator, you never become an ex-Naval aviator or even a former Naval aviator. Once you’re in the club, you’re there forever.

Air Force, Army and civilian pilots have been snorting at this snobbery for decades, but it focuses on an important issue: Is the act of becoming a pilot so utterly distinguishing that it places you forever in a separate segment of humanity? Or, closer to home, is the act of putting it on the line on a racetrack similarly a passage so dramatic that you thereby earn the right never to be an “ex,” in truth if not in conversational style?

To my surprise, I decided that, like becoming a pilot, becoming a racer really is life-changing. Anti-elitists might not agree, but I figure that so few people choose to look for the edge of the envelope on a racing bike that it is an act of social severance, one that irrevocably puts you in a very elite club. Whether you pitch an MXer over the whoops or slide a miler on the very edge of the Great Gulp or wait until the last braking mark whips past your GPz’s front tire before you grab all the brake God has given you, you do in fact belong to a select bunch of people. And you do in fact deserve to consider your racing a distinction for life. When you quit (as all of us eventually must), you cease active competition, but you do not lose your distinction.

I think we value this too lightly. Perhaps it is because of our forelockknuckling approach to society at large, in which we too often try to blend in, to act as if riding (or racing) a motorcycle is nothing special. But special it is. The act of riding a bike is a statement about life, about the limitless uses of this moment, the next, and the one beyond that. It is the antithesis of a college tee shirt on a middle-aged chest; it is an act which proclaims that the best is yet to come, rather than years behind.

It is especially ironic that this elementally optimistic aspect of riding is so often misconstrued by fearful nonriders as some kind of “death wish.” It could hardly be less so, and hardly be more life-affirming. Of all the humans who climb in or on a piece of machinery to move past a walking pace, the motorcyclist is the most avowedly optimistic: Confronted with the greatest hazard, he (or she) cheerfully plunges ahead, savoring each delicious second of balance and control, eternally hopeful that his/her ability can conquer the vicissitudes that inevitably lie around the next corner.

It would have been fun to talk about all this with some of those former Ivy League types, but I never got the chance; the tee-shirt war quickly fizzled out. I’m not sure why, exactly. Maybe it had something to do with the lawyer who changed out of his Brooks Brothers uniform into his own talking tee, which was impossible to go one-up on. Emblazoned on his chest was a huge “U of B” and below it the words, “University of Budweiser.”

Like I said: You can learn a lot from tee shirts. —Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

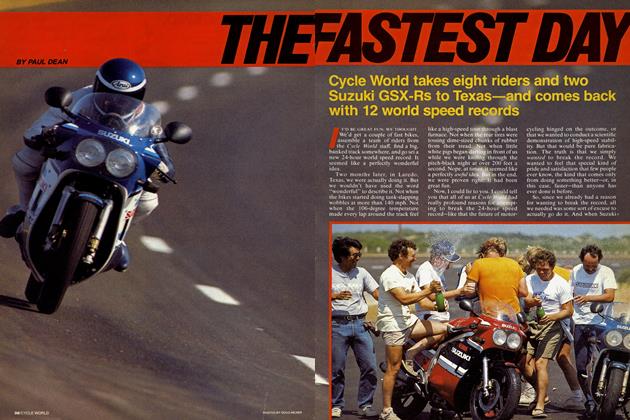

EditorialThe Making of A Record

DECEMBER 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Walkman Cometh

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

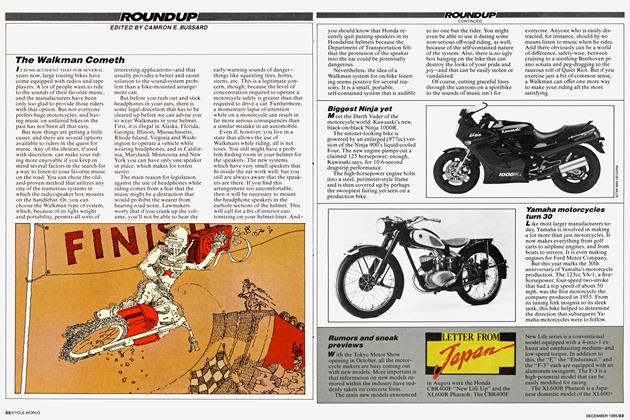

RoundupLetter From Japan

DECEMBER 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

DECEMBER 1985 By Alan Cathcart -

Special Feature

Special FeatureThe Fastest Day

DECEMBER 1985 By Paul Dean