THE FASTEST DAY

SPECIAL FEATURE

PAUL DEAN

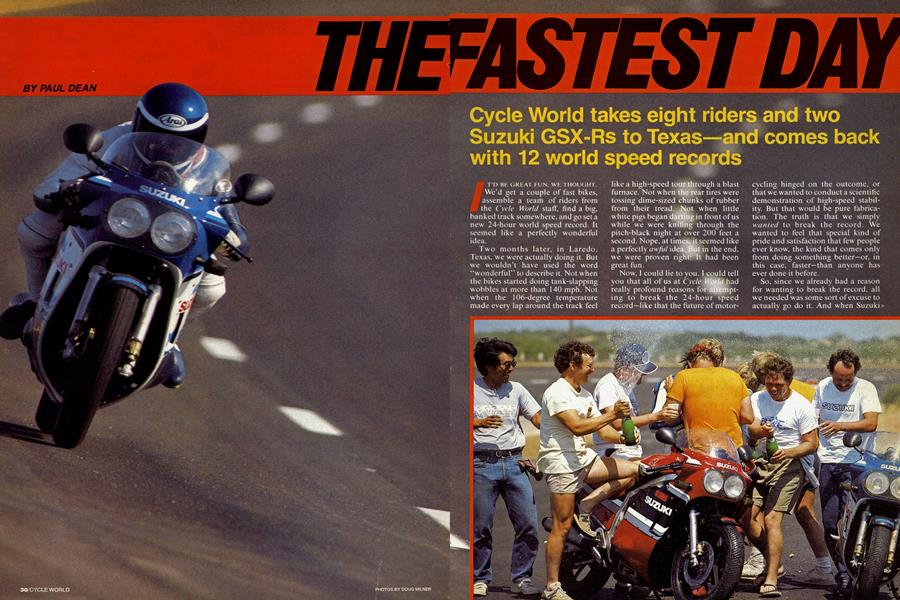

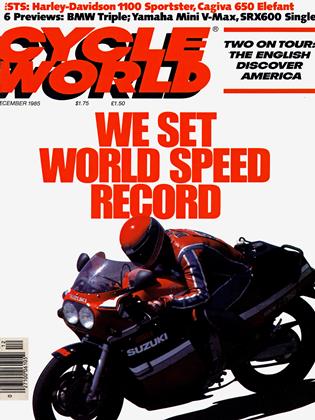

Cycle World takes eight riders and two Suzuki GSX-Rs to Texas—and comes back with 12 world speed records

IT'D BE GREAT FUN. WE THOUGHT. We’d get a couple of fast bikes, assemble a team of riders from the Cycle World staff, find a big, banked track somewhere, and go set a new 24-hour world speed record. It seemed like a perfectly wonderful idea.

Two months later, in Laredo. Texas, we were actually doing it. But we wouldn’t have used the word “wonderful” to describe it. Not when the bikes started doing tank-slapping wobbles at more than 140 mph. Not when the 106-degree temperature made every lap around the track feel like a high-speed tour through a blast furnace. Not when the rear tires were tossing dime-sized chunks of rubber from their tread. Not when little white pigs began darting in front of us while we were knifing through the pitch-black night at over 200 feet a second. Nope, at times, it seemed like a perfectly aw ful idea. But in the end. we were proven right: It had been great fun.

Now, I could lie to you. I could tell you that all of us at Cycle World had really profound reasons for aWempting to break the 24-hour speed record—like that the future of motorcycling hinged on the outcome, or that we wanted to conduct a scientific demonstration of high-speed stability. But that would be pure fabrication. The truth is that we simply wanted to break the record. We wanted to feel that special kind of pride and satisfaction that few people ever know, the kind that comes only from doing something better—or, in this case, faster—than anyone has ever done it before.

So, since we already had a reason for wanting to break the record, all we needed was some sort of excuse to actually go do it. And when Suzuki: announced that the GSX-R750, the revolutionary bike that had wowed the industry in Europe, Japan and Australia this year, would be available in this country in 1986, we didn’t have just any old excuse; we had the perfect excuse.

See, Mr. Estuo Yokouchi and his team of engineers at Suzuki performed some impressive magic with the GSX-R750. They did the undoable and built a motorcycle that had at least 20 percent more horsepower than anything else in its class, yet weighed at least 20 percent less. Obviously, this resulted in a power-toweight ratio that let the GSX-R rewrite the book on 750-class performance; but the fact that Yokouchi & Co. had burned the engineering candle at both ends, so to speak, raised some serious doubts about the bike’s durability. Riders in the markets where the GSX-R was being sold began wondering if maybe it were a nickel rocket, a bike that would briefly light up the sky with its blazing performance and then fade into a smoking pile of rubble before the nubs had worn off the tires.

A serious question, to be sure. And the knowledge that this bike would soon start appearing in American dealerships prompted us to provide an answer. But, we wondered, how could we find that answer? A normal road test wouldn’t involve enough mileage to say much about the bike’s endurance, and a long-term test would require the passage of too much time. What was needed was a quick test of endurance, something that would let us press the bike to its limits of durability in the shortest possible time, something that would allow us to reach a meaningful conclusion about the GSX-R’s staying power . . . something, not coincidentally, like an all-out assault on the world 24-hour speed record for 750class motorcycles. If we succeeded, we’d have plenty to talk about. If we failed, the subject matter would be different, but we’d still have something to talk about.

Besides, the existing 750-class record didn’t seem as though it would be all that difficult to surpass. It had been set in 1977 by a Kawasaki KZ650 that averaged 117.149 mph around Daytona Speedway for the 24-hour period. We figured that with the aid of the GSX-R’s 140-plus-mph top speed, we’d be able to break the record by a sizable margin, even if we didn’t run flat-out for 24 hours.

To improve our chances for success, we decided to use two bikes and conduct two simultaneous record attempts, just as Kawasaki had done. There would, however, be a few significant differences between our record run and Kawasaki’s. For starters, we would use bone-stock motorcycles, whereas the KZ650s that set the record in 1977 had been heavily hot-rodded to boost their performance. I know; I was a rider on one of the two teams that participated in that attempt. Those bikes were perfectly legal, however, even though they were by no means stock. The sanctioning body for motorcycle world records, the FIM (Federation Internationale d’Motocycliste), permits engine and chassis modifications of virtually any kind in record runs. The only requirements are that the vehicle have two (or, in the case of a sidecar rig, three) wheels and an engine that does not displace more than the class limit. The FIM’s rationale is simple: The more a motorcycle, particularly its engine, is modified for added speed, the less reliable it is likely to be.

Another key difference between our attempt and Kawasaki’s would be that we, as independent entities with no ties to the manufacturer, would control matters from beginning to end, whereas Kawasaki was in charge of its own 1977 event. We were attempting, you see, to make a statement about the reliability of production-line motorcycles, so we had to have complete control over all the proceedings. Otherwise, certifying that the bikes were Stockers would be difficult if not impossible (see Editorial, pg. 5).

In addition, all of the riders would be members of the Cycle World staff in one way or another; we wanted this truly to be our record, not that of a collection of hired racers. So the team would consist of Managing Editor Ron Lawson, Feature Editor David Edwards, Senior Editor Ron Griewe, Associate Editor Camron Bussard, East Coast Editor Steve Thompson, Advertising Director Larry Little, and, of course, me. Technical Editor Steve Anderson could not participate because he was in Germany covering the introduction of BMW’s new K75 Triple; so to round out the eight-rider team we chose Doug Toland, an accomplished local roadracer who often appears in the pages of Cycle World, dragging his knee through a corner on a test bike. And we agreed that all eight team members would ride both of the bikes so that everyone would own a piece of the record (if we got it), no matter which bike succeeded.

We also decided to use a location other than Daytona for our record run, and finally settled on Uniroyal Tire Company’s high-speed test track at its Laredo Proving Grounds in Laredo, Texas. We picked this facility because it seemed the ideal place for a record attempt. The track is a perfect circle exactly five miles in length and four lanes (52 feet) wide, and it had been the recipient of a $2.2-million resurfacing just weeks before our record attempt. The track also has parabolic banking that, in a car, allows a driver to circulate at about 140 mph in the upper lane with his hands oft of the steering wheel. On the GSX-Rs, we could run in the 135-to140-mph range and have that same kind ot neutral steering at the top of the second-highest lane.

This meant we could keep the bike more or less perpendicular to the track at all times, a point that was of no small importance. Tire life, particularly at the rear, can be amazingly short at the kinds of steady speeds we would be attaining; and we knew the record would be tough to beat if the bikes spent much of their time in the pits undergoing wheel changes. So by practically eliminating the lateral scuffing that a tire suffers when leaning around corners, we hoped to minimize the number of tire changes that would be required.

In fact, we decided to try to eliminate tire changes altogether by replacing the original-equipment Bridgestone tires with Metzelers that had been designed for greater longevity. The stock tires are excellent for the GSX-R’s intended sport usage, but they weren’t designed for long life at world-record speeds. So when Metzeler learned of our record attempt and offered to put its endurance-racing expertise to good use, we agreed to let the factory in Germany build us a small batch of long-mileage tires. The tires incorporated the MBS (Metzeler Belted System) belted construction featured in the company’s new line of touring tires, but with the familiar ME99 rear/ ME33 front sport-series tread pattern and the fairly hard compound used in Metzeler’s sport-touring tires.

Our justification for this switch was simple: We were going to be testing motorcycles, not tires, and using more-durable rubber would simply allow us to keep the bikes out on the track more of the time. After all, if the GSX-Rs were going to break, they wouldn’t do it in the pits.

For the same reasons, we also increased the fuel capacity of the GSXRs. The bikes we used were Australian-spec models that normally have five-gallon tanks, but the factory had fitted them with the 5.8-gallon tanks that will be standard on U.S. models. Still, the tremendous fuel consumption up around 140 mph (about 15 mpg) meant that we would only be able to go about 80 miles, or less than 35 minutes, on a tank of gas. So at the last minute, we equipped each bike with a nifty, 3.7-gallon auxiliary gas tank that had been hand-fabricated by Suzuki in Japan to resemble a rather large, roadrace-style seatback. We figured that with an overall capacity of 9.5 gallons, the bikes should be able to go almost a full hour, or about 140 miles, between refuelings.

We figured wrong. And we weren't very far into the record attempt when we began to understand just how wrong. Under the supervision of offi cial FIM steward Jack Dolan and his assistant, AMA timekeeper Gary Cagle, we sent the first rider, Camron Bussard, out onto the track on the red GSX-R precisely at noon on Wednesday. He was followed exactly one minute later by Ron Lawson on the blue GSX-R. Bussard, however, had difficulty with the extreme heat and the 140-mph wind's never-end ing attempt to strangle him with his helmet strap. and he pulled back into the pits after only about 35 minutes on the track. We're lucky he did. During the refueling, we noticed that the main tank was just about dry, but that the auxiliary tank was still full to the brim. Obviously, something had prevented the tail tank from draining. We made a quick check of the tank's venting system and its other plumb ing before the next rider-which was me-was sent out to take his turn on the red bike.

As a precautionary measure, Law son was signaled in early just in case the blue bike had a similar problem.

It did. And after a brief, unsuccessful attempt to find the cause, the pit crew decided to put the next rider, Larry Little, on the bike and send it back out while everyone else scratched their heads and tried to figure out why the tail tanks weren't draining.

It quickly became an exercise in futility. We tried everything we could think of over the next hour or so, but to no avail. What's more, the riders began reporting that the bikes would start wobbling about halfway through each session out on the track. Apparently, the wobbling was being caused by a rearward shift of the weight bias as the main tank drained and the tail tank stayed full. And the really bad news was that the wobbles were continually growing worse.

Just past the three-hour mark, the problem began resolving itself. First, the tail tank on the red GSX-R split a seam and began dumping fuel all over the rear of the bike. Fortunately, the rider, Ron Lawson, was able to get back into the pits without incident. We quickly yanked the tank off and sent the bike back onto the track with Larry Little aboard, and the wobbling promptly stopped altogether. Shortly thereafter, David Edwards, who had been out on the blue GSX-R only about 20 minutes, pulled in and, with the look of a man who had just seen God, proclaimed that the bike had begun wobbling so violently that he could no longer control it. So off came its tail tank, too: and, like the red bike, when it went back on the track, the wobbling ceased. Not only that, both bikes started turning the fastest laps they had posted up to that point.

Surprisingly, despite all the time that had been wasted in the pits due to tail-tank troubles, we had successfully captured the two-hour record on the blue GSX-R, and the three-hour record on the red GSX-R (see “For The Record,” pg. 39 ). We knew from the outset that the one-hour record of 150.542 mph (set by Gene Romero on a Yamaha TZ750 roadracer in 1974) was out of reach, simply because a stock GSX-R won't go quite that fast. But we calculated that if no other major problems arose in the 20plus hours ahead of us, and if we rode flat-out and wide-open, we’d be able to demolish all of the remaining hourly records.

The bikes didn’t seem to mind in the least, for they whooshed around the track hour after hour at absurdly high rpm without missing so much as a beat. At the slowest point of each lap, which occurred as the bikes hit a headwind that prevailed during the entire 24 hours, they never dropped below 10,000 rpm; and at the fastest, which happened as the bikes would catch that same wind when heading in the other direction, they often would exceed their 1 1,000-rpm redline by as much as 400 rpm.

But we figured we’d eventually need the cushion being built-up by that flat-out riding. For one thing, not having the auxiliary fuel tanks meant that we'd need to make quite a few more pit stops than originally planned. Moreover, the 130-degree track-surface temperature during the day was playing havoc with tire life, and it was becoming increasingly clear that we would not be able to go the distance on one set of tires per bike. Gary Gallagher, the Metzeler representative on hand for the entire event, had been measuring tire wear at each pit stop, and he estimated that the first set of rear tires would not last more than 10 hours.

He was right. Just before 10 p.m., he announced that the rear tires were shot, so we called the bikes in, one at a time, for new rear rubber. Three Suzuki representatives (T. Shimizu, one of the factory engineers who designed the GSX-R engine; Aki Goto, Manager of U.S. Suzuki’s Product Development department; and Shoji Tanaka, Product Development Supervisor) who had come along only to “observe” said they were very familiar with the GSX-R’s rear-wheel arrangement and asked if they could perform the wheel changes. We agreed—and it proved to be one of the best decisions we made during the entire attempt. The trio swapped the wheels so quickly and efficiently that they seemed like the Japanese equivalents of the Wood Brothers, the acknowledged speed kings of stock-carracing pit stops.

As we sent the bikes back onto the track with new tires, things were looking pretty rosy. We had shattered all the hourly records from two to nine hours, and the bikes were still running perfectly. All of us riders had settled into a nice, fast rhythm on the track, and we had learned how to cope with the effects of sitting for more than a half-hour atop a motorcycle that is punching a 145-mph hole in the wind. Everyone came up with his own chin-strap fix in an attempt to relieve the aching jawbone caused by the air trying to wrench his helmet off his head; and each rider developed a style of racer-tuck that allowed him to stay scrunched-up in that position every second he was on the track. And with the comparatively cooler temperatures that would prevail between 10 p.m. and noon the next day, we hoped to finish the attempt with no further changes.

Wrong again. For reasons that are not yet completely clear, even to Metzeler, the new rear tires began tossing chunks of rubber from their center tread area. We weren’t aware of this problem until the red GSX-R came in for its first scheduled pit stop after the tire change, but the rider, Bussard, said the bike had felt squirrelly in the rear. At first we figured that it was a fluke, that we had just gotten a bad tire; so the three Suzuki executives carried out another lightning-fast wheel change, and we sent the red bike back onto the track.

Whatever it was, it apparently was no fluke; just minutes later, the blue bike came in with the same problem. After yet another speedy tire change, we sent it back onto the circuit, only to have the red bike come in a few laps later with a chunked rear tire, followed a few minutes after that by the blue bike with the same problem. The three Japanese again dutifully performed their wheel-changing miracles, but afterward, as we watched the blue bike accelerate off into the night, a sinking feeling began to creep in. We realized that if this continued, we would have to abort the attempt, if for no other reason than we were running out of tires.

Due to the fact that there had been no tire problems during the blistering-hot daylight hours, our best guess was that the lower ambient and track temperatures were somehow to blame. Maybe, we supposed, the cool rear tires were being heated up too quickly just in the center section, thus causing a rapid local expansion of the tread that was making the rubber first split and then chunk. We decided to try warming up the new tires more gradually by touring the track at a greatly reduced pace—say, about 80 to 100 mph—for the first few laps before returning to top speed.

It worked; and the rest of the night and into the morning, the tires gave no more problems. The bikes ran flawlessly as we surpassed the records for 10, 11 and 12 hours. The only adventures were provided by a few small, white boars, called javelinas, that insisted on dashing out in front of the bikes in the middle of the night. They weren’t very big, but the thought of centerpunching one at those speeds was terrifying.

Daybreak marked the departure of the dancing pigs but the return of tire problems. At around 6 a.m., as I climbed off the red GSX-R after a routine session on the track, Gallagher’s voice suddenly broke the morning silence. “Oh, no\ More chunking,’’ he exclaimed as he stared in disbelief at the rear tire. Worse yet, we had no more rear Metzelers. But without the slightest hesitation, Gallagher grabbed a rear wheel fitted with a stock Bridgestone rear tire and rolled it over to Shimizu, Tanaka and Goto. "It's not a Metzeler, " said Gallagher, "but at this point, the record is more important than the brand of tire we use." I thought it was the classiest, most unselfish act of the entire record attempt.

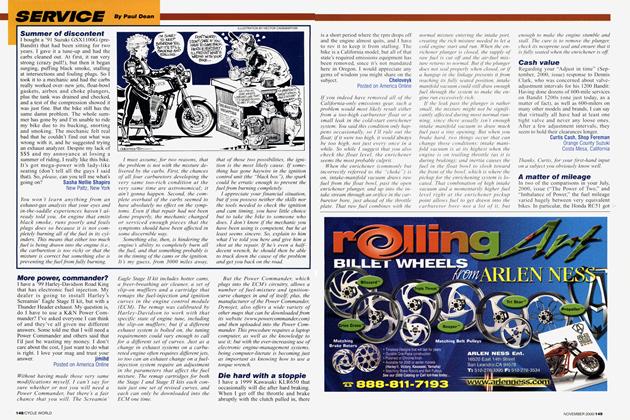

So, after what we prayed would be the final tire change, we settled back and nervously waited for either bike to complete its 568th lap of Laredo's five-mile track. Because when that milestone was passed, which we esti mated would be just after 10 o'clock in the morning, the 24-hour record would be ours. In 1977, the record setting Kawasaki had traveled 28 11.6 miles in 24 hours; and as long as we bettered that distance by at least one percent, or a total of 2839.7 miles, Cycle World would own the record, even if we stopped right at that point. At 10:14 a.m., as everyone in volved in the attempt ran out on the track and jumped up and down like a bunch ofjubilant racers who had just clinched a world championship, Ron Lawson rocketed past the start/finish line on the blue GSX-R to complete lap 568. We had done it! The 24hour world speed record was ours.

We continued with both bikes, naturally, just to see how far we could escalate the record. But our troubles were not yet at an end. As Steve Thompson took over the blue GSX-R from Little with just about an hour to go, Gallagher noticed the early stages of chunking on the rear tire. So, as we had done with the red GSX-R a few hours earlier, we in stalled the bike's original Bridgestone rear tire. But before the final rider, Doug Toland, would zoom past the start-finish line for the last time at one minute past noon, even that Bridgestone would be showing signs of splitting and chunking.

But by then, it didn't matter. We already had what we had come to get. And despite the plethora of pit stops, our average sneed for 24 hours was right on-target. We had hoped to exceed Kawasaki’s mark of 1 1 7.149 by at least 10 mph, and the blue GSXR’s average speed was 128.303 mph. The red bike was just a tiny fraction behind with a 128.059-mph average.

All these records are, of course, subject to final FIM approval, which should have occurred by the time you read this. But it was only after the attempt was over and I was checking through the FIM record book that I made a thrilling discovery: Our average speed for 24 hours was a record not just for 750-class motorcycles, but for all motorcycles. Indeed, no one, on any kind of a motorcycle of any size or configuration, had ever gone faster for longer. We had set an absolute world record.

For that accomplishment, we have received congratulations from motorcycle people all around the world. And we’re grateful for their acknowledgement and their kind words. But the real heroes, the members of the team that actually deserve the most credit, are the motorcycles. They had the tough job: They had to run wideopen and at redline for 24 hours and more than 3000 miles; all we had to do was sit on them and hold their throttles open. What’s more amazing is that the only things that kept both bikes from having a much higher average speed, possibly as high as 135 mph, were the tires and the auxiliary gas tanks—neither of which was part of the stock motorcycles. If you’re looking for a testimony to the durability of the GSX-R750, that’s certainly a mighty fine one.

But ifit still isn’t enough, consider this; As the blue GSX-R screamed past the start/finish line on its very last lap, I commented to our group of tired but happy record-setters that the bike would only have to go another 662 miles, or about five hours, to beat the 48-hour world speed record. Thirteen weary bodies stared back at me in disbelief, not knowing whether to laugh or to find the nearest tree and string me up from it.

Anyway, it was a moot point: Uniroyal wasn't ready for any more of our 145-mph carryings-on, for we had reserved the track only for this particular 24-hour period; the tires weren’t ready, either, and we were altogether out of fresh rear rubber; and the riders and support personnel, all of whom had paced themselves for a 24-hour attempt, were ready only for bed. But the motorcycles, those magnificent GSX-R750s, were ready. They were running every bit as well as, if not better than, they had been in the very beginning. And I, for one, wouldn’t have hesitated for a moment to keep them out on the track and let them run, flat-out and wideopen, for another 24 hours.

Now, that would have been a perfectly wonderful idea . . . wouldn’t it?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Making of A Record

DECEMBER 1985 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeBattle of the Talking Tees

DECEMBER 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Walkman Cometh

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

DECEMBER 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

DECEMBER 1985 By Alan Cathcart