RANDY GREEN, SPEEDWAY STAR

RACE WATCH

RON LAWSON

America’s unknown hero

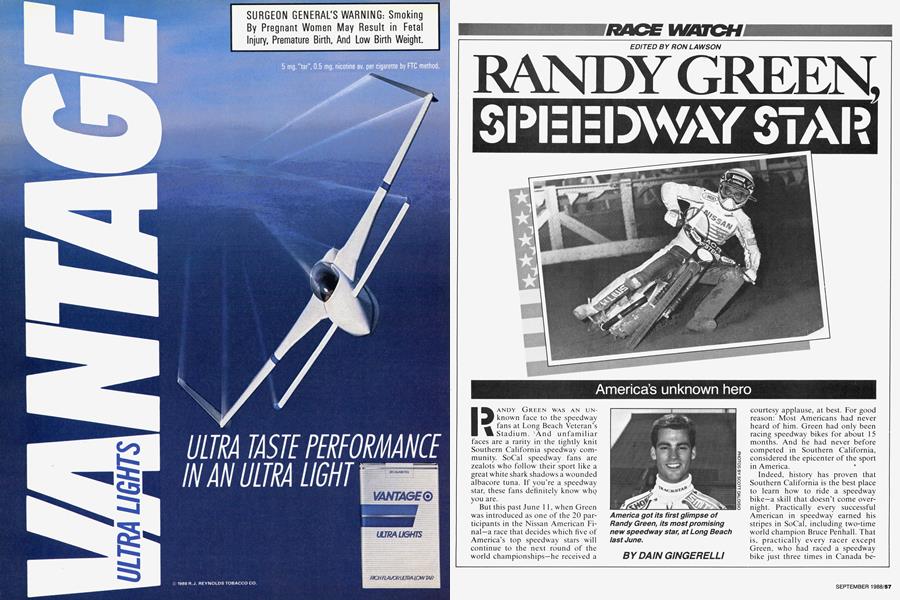

RANDY GREEN WAS AN UNknown face to the speedway fans at Long Beach Veteran’s Stadium. And unfamiliar faces are a rarity in the tightly knit Southern California speedway community. SoCal speedway fans are zealots who follow their sport like a great white shark shadows a wounded albacore tuna. If you’re a speedway star, these fans definitely know whQ you are.

But this past June 1 1, when Green was introduced as one of the 20 participants in the Nissan American Final—a race that decides which five of America’s top speedway stars will continue to the next round of the world championships—he received a courtesy applause, at best. For good reason: Most Americans had never heard of him. Green had only been racing speedway bikes for about 1 5 months. And he had never before competed in Southern California, considered the epicenter of the sport in America.

DAIN GINGERELLI

Indeed, history has proven that Southern California is the best place to learn how to ride a speedway bike—a skill that doesn’t come overnight. Practically every successful American in speedway earned his stripes in SoCal, including two-time world champion Bruce Penhall. That is, practically every racer except Green, who had raced a speedway bike just three times in Canada before going to England to race in British League competition.

Green was an experienced AMA Expert dirt-tracker before turning to speedway in 1986. Only a month after his first speedway race, he tried out for a spot on a British League team. The Hackney Kestrals hired him that same day, and he soon found himself in his first league race. A Cinderella story, to be sure; you just don’t waltz over to England and start racing in British League. That’s like going directly from high-school football to a starting spot on the Los Angeles Raiders.

But Green had a clear understanding of racing. He first started competing on mini-bikes when he was just five years old, and became an AMA Expert by age 17. He almost won his first-ever Camel Pro Series race, the Houston short-track National, where he maintained nearly a straightaway lead for most of the event over twotime National Champion Randy Goss and short-track specialist Terry Poovey. But with just five laps to go, Green began to fade, and Poovey and Goss eventually overtook the plebe racer from Washington. Green hung on for third.

Of that race in 1983, Green shrugs, saying, “I just rookied out. Everybody on the circuit knows about that race.” Three years later he won the AMA’s West Coast Regional Championship, but the Houston race still hung like a dark cloud. So did the gloomy future of AMA flat-tracking. Even at 22 years of age, Green knew that only a handful of riders were able to earn a decent living on the Camel Pro circuit.

So he looked for greener pastures, and ultimately decided that speedway was the answer. After all, several American racers were making good money racing in British League. At the urging of two friends, Led Smezek and Yogi Sylvert, he tried speedway for the first time at a local Canadian race. He won all three races he entered that night.

“It’s pretty amateurish up there,” Green admits, “not as competitive as in Southern California.” Even so, his performance was proof enough for Smezek and Sylvert, who called in a few favors from friends in England. By the end of the year. Green had an audition with the Hackney Kestrals, a team in search of an American

rider.

“The timing was right,” recalls Green. “Hackney was moving up from the National League—which has only British riders—to the British League. They wanted an American rider, and I was their man.”

Green’s task was not made any easier by the short time he had in which to learn the technique of riding speedway bikes, machines like no other motorcycles on earth. They have an extremely steep steeringhead angle that helps them broadslide controllably, but only if the rider barrels into the turn with the throttle wide open; turn off the gas, and the bike will stand up and head straight for the wall.

The equation gets even more lopsided when you consider power-toweight ratios. A typical speedway bike weighs less than a 125cc motocrosser, yet its 500cc single-cylinder four-stroke engine cranks out about 65 horsepower. Further testing a rider’s manhood is the fact that speedway bikes don't have brakes. To slow down, you either pitch the bike sideways at full-throttle, or fall over.

It’s no wonder, then, that young American riders train for years on the Southern California bull-ring arenas to earn a slot on a British League team. Says Green, “I knew going in it would be very hard. I know you’re normally supposed to pay your dues in California first. I didn't.”

Green soon learned just how hard it would be. After seven race meets, he carried only a 5.36-point average (of a possible 1 2). That was not good enough, and Hackney management removed him from the starting lineup. As Green puts it, “I was basically dismissed.”

Green was at a crossroads. According to British law, foreign riders in British League must file for employment status and maintain at least a six-point average in league racing, or be expelled from the country. But league officials successfully bargained with the British government to allow Green another chance. After he got the okay, the Bradford Coalite Dukes picked him up as the second Yank on the squad behind Ron Pfetzing (another ex-flat-tracker).

Resolved to succeed. Green trained and practiced with purpose last winter. He entered the 1987 season a more polished speedway racer,

and as of the American Final in June. carried a 6.5-point average in league CO fl1 Pet it ion.

Furthermore, he had been the sixth-and final-qualifier at the the long-track qualifying event in West (Jermanv only a few weeks before. His sixth-place finish in that meet transferred him to the next elimina tion round toward the long-track world championship. (Long-track racing is held on 1 000-meter tracks. while speedway is on 400-meter tracks.)

Certainly, Green's U.S. mile and half-mile experience played a major role in his long-track success. But for the American Final, run on the com pact 440-yard oval at Long Beach, Green would have to rely on his schooling over the previous 1 5 months. At stake was one of five transfer spots to the Inter-Continen tal Final in Coventry. England. on July 10. Ultimately, the riders who survive this and a third elimination round are eligible for the World Fi nal, to he held this \`ear in Vojens. Denmark. on Se~temher 3.

There was nothing impressive about Green's first heat at Long Beach. A poor start left him scrunched in the middle of the fIve hike pack. and he crashed in Turn One. While the rest of the field headed onto the back stretch. Green dusted decomposed granite off his leathers and hike. Rcsuh: Last place. no points. and a few headaches for his long-time friend and mechanic. Carl Blornfeldt.

In his next heat. Green settled down to finish second. earnin2 his first three points of' the evening. Fol lOwirl2 two third-place finishes. Green finally won his fifth and final four-lap heat. His 11 points were not enough to transfer him to the (`oven try race, hut he had gotten valuable exposure to Southern California st'~le speedway.

Green headed back to En~land with more confIdence, having finally met the Southern California riders Ofl their home turf and proven himself. At last he had earned his stripes, paid his dues. And at next year's Ameri can Final, maybe there'll he a few more hands clapping when Randy Green is introduced. That would he only fitting for the man who could he the United States' next speedway world champion.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Racer's Hedge

September 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeSunday Rider: No Apologies

September 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsChain Tension

September 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupCounter-Intuitive

September 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

September 1988 By Alan Cathcart