Counter-intuitive

ROUNDUP

STEVE ANDERSON

CHANCES ARE YOU REALLY DON’T KNOW HOW TO RIDE A motorcycle. We’re not trying to be insulting, but the truth is that very few motorcyclists are aware of many of the control operations they perform when riding. But for the most part, this doesn’t matter; if your body knows how to operate a motorcycle (and if you ride, it certainly does), then a complete understanding of what you are doing on a bike is no more vital to you than a complete understanding of the physics of walking.

Until an emergency arises.

We were recently reminded of this when our Editor became an in-depth observer of the aftermath of a motorcycle-involved accident. The details aren’t terribly important—the accident began when a truck made a left turn in front of a motorcycle—except that the crash could have been avoided. Instead, the reflexive action of the motorcyclist made the situation far worse, for he actually turned into the side of the truck after it had already crossed in front of him, and he was severely injured as a result.

According to Harry Hurt’s oft-quoted study of motorcycle crashes, this accident followed a common pattern: a rider steering into an obstacle he was trying to avoid.

Behind the pattern is a reason: the way motorcycles turn. Above walking speeds, the only way to initiate anything but the most gradual of turns is by countersteering—that is, by steering the front wheel left to turn right, or right to go left. The whole idea might seem bizarre and unnatural, particularly to car drivers,

but it’s how bikes turn.

To understand countersteering, let’s look at a righthand turn in detail. To start that turn, you first steer the handlebars not to the right but very slightly to the left (which is why it is called countersteering). Often, this is done by leaning your body slightly to the right, which tends to make you press forward on the right handgrip. (That’s one reason many riders mistakenly think that body lean initiates turns, instead of countersteering.) As the front wheel aims to the left, it does two things. It steers to the left, which causes the bike to fall to the right; and since the spinning front wheel acts as a gyroscope, the steering of the wheel to the left causes a gyroscopically induced reaction that additionally causes the bike to lean right. Then, as the bike approaches the desired lean angle, you have to turn the handlebars back to the right to prevent the bike from falling over completely. And once the right-hand turn reaches a steady state, the front wheel will be turned in very slightly to the right.

These handlebar movements are so small that most people don’t know they’re making them. But whether or not you’re consciously aware of countersteering makes no difference: It’s not an option. It’s a must, for you can’t ride a motorcycle without it.

Unfortunately, in panic situations, this steering behavior can easily work against you. In an adrenaline-pumping emergency, it’s easy to fall back on automobileconditioned reflexes and do what seems the natural thing: turn the handlebars away from what you want to avoid. But that only causes a bike to lean and steer toward what you want to avoid, a situation that could leave you in a world of hurt.

The alternative is to be conscious of countersteering, and work to make it part of your reflexes. First, if you have any doubts that motorcycles indeed do steer in this way, you need to convince yourself otherwise. To do so, try riding on a straight, empty section of road with your left hand held behind your back. Hold your body perfectly still and observe how the bike reacts even to small movements of the handlebars.

Second, practice conscious countersteering. Again, on a straight, empty road, practice dodging potholes or oil stains, pushing forward on the right handgrip to turn right, on the left to go left.

When you feel comfortable with that, notice what countersteering does in a long, constant-radius turn. This is an important observation, since you also change your lean angle with countersteering, even when you're already in a corner. By turning the bars slightly to the outside of a turn, you lean over farther, tightening your line. Having that information programmed into your reflexes could prevent a crash if you enter a decreasingradius corner going too fast.

There’s one last secret about countersteering: Consciously doing it makes motorcycle riding more fun.

With your mind and body working together when riding, you’ll feel so much more in control that you’ll wonder why this isn’t a mandatory part of rider training.

Ánd that’s a good question in itself.

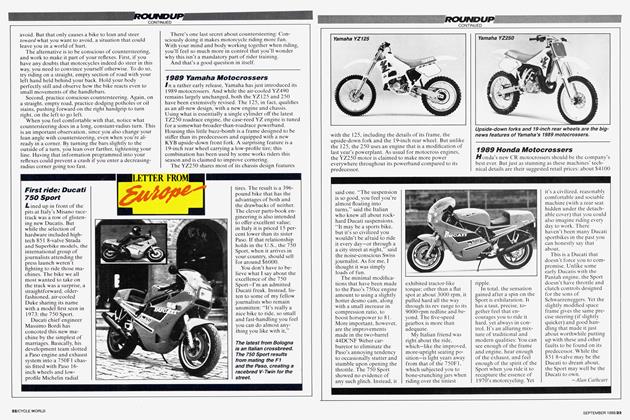

1989 Yamaha Motocrossers

In a rather early release, Yamaha has just introduced its 1989 motocrossers. And while the air-cooled YZ490 remains largely unchanged, both the YZ125 and 250 have been extensively revised. The 125, in fact, qualifies as an all-new design, with a new engine and chassis. Using what is essentially a single cylinder off the latest TZ250 roadrace engine, the case-reed YZ engine is tuned fora somewhat-broader-than-roadrace powerband. Housing this little buzz-bomb is a frame designed to be stiffer than its predecessors and equipped with a new KYB upside-down front fork. A surprising feature is a 19-inch rear wheel carrying a low-profile tire; this combination has been used by some works riders this season and is claimed to improve cornering.

The YZ250 shares most of its chassis design features with the 125, including the details of its frame, the upside-down fork and the 19-inch rear wheel. But unlike the 125, the 250 uses an engine that is a modification of last year’s powerplant. As usual for motocross engines, the YZ250 motor is claimed to make more power everywhere throughout its powerband compared to its predecessor.

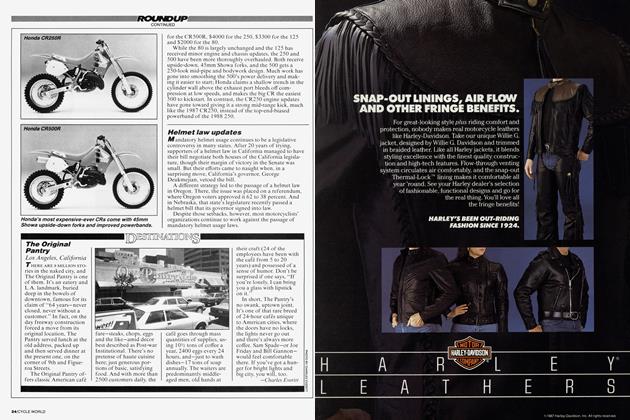

1989 Honda Motocrossers

Honda’s new CR motocrossers should be the company’s best ever. But just as stunning as these machines’ technical details are their suggested retail prices: about $4100

for the CR500R, $4000 for the 250, $3300 for the 125 and $2000 for the 80.

While the 80 is largely unchanged and the 125 has received minor engine and chassis updates, the 250 and 500 have been more thoroughly overhauled. Both receive upside-down, 45mm Showa forks, and the 500 gets a 250-look mid-pipe and bodywork design. Much work has gone into smoothing the 500’s power delivery and making it easier to start; Honda claims a shallow trench in the cylinder wall above the exhaust port bleeds off compression at low speeds, and makes the big CR the easiest 500 to kickstart. In contrast, the CR250 engine updates have gone toward giving it a strong mid-range kick, much like the 1987 CR250, instead of the top-end-biased powerband of the 1988 250.

Helmet law updates

Mandatory helmet usage continues to be a legislative controversy in many states. After 20 years of trying, supporters of a helmet law in California managed to have their bill negotiate both houses of the California legislature, though their margin of victory in the Senate was small. But their efforts came to naught when, in a surprising move, California’s governor, George Deukmejian, vetoed the bill.

A different strategy led to the passage of a helmet law in Oregon. There, the issue was placed on a referendum, where Oregon voters approved it 62 to 38 percent. And in Nebraska, that state’s legislature recently passed a helmet bill that its governor signed into law.

Despite those setbacks, however, most motorcyclists’ organizations continue to work against the passage of mandatory helmet usage laws.

View Full Issue

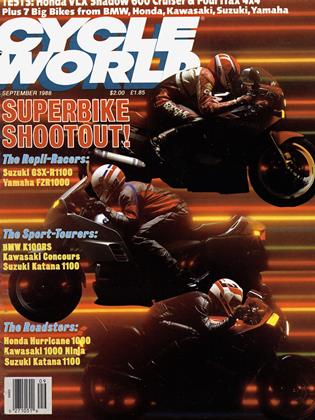

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Racer's Hedge

September 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeSunday Rider: No Apologies

September 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsChain Tension

September 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

September 1988 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupDestinations

September 1988 By Charles Everitt