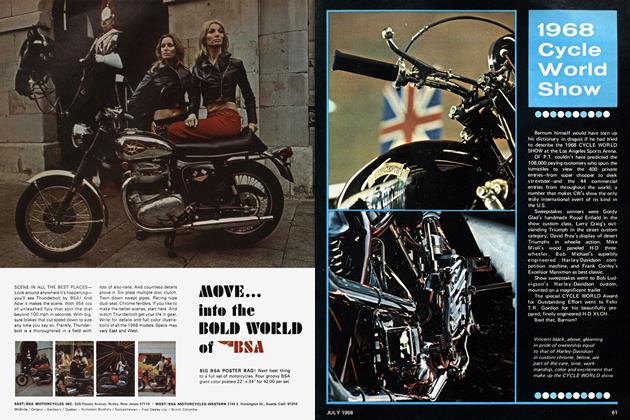

TAKING IT TO THE NINES

To go faster than you ever dreamed, all it takes is money

STEVE ANDERSON

With the tach hovering at 6000, you stretch your legs out behind, grip the seat with your thighs, and wait for the green light, then... full throttle and dump the clutch. Oomph!— The hand of God shoves the bike forward, violently, and you chin yourself on the handlebar, itself suddenly light, free of control. You strain to pull your legs, weighted with acceleration, forward, up to the pegs, just in time to hit the clutch lever and the shifter, the throttle still full-on. The bike rocks back, there's a twitch of wheelspin, and the furious bellow of the exhaust deepens in a new rush. But the tach needle races back to the red, and you stab at the shifter for third. Another change of pitch, and, just marginally, as the scenery blurs past more quickly, your mental load slows. When you shift to fourth, the bike is still pulling hard, but the tapering off of acceleration makes things feel relaxed compared with the first few seconds. As the timing lights fly toward you at 135 mph, you notice for the first time just how fast you're traveling. You pass the finish line, having covered 1320 feet, further than four football fields,

in less than 10 seconds. Finally, for the first time since the launch, you breathe.

0 PARAPHRASE WHAT INDIANAPOLIS 500 WINNER Danny Sullivan once said, drag racing is like a drug they don't sell. The brutal acceleration of a really fast motorcycle can be as addictive as pium. and, as with a drug, you can develop a tolerance; )nce you have adapted to a certain performance level~you iave to go looking tor the next. .

At 1e~st, that'~ our excuse. The quickest of current superbikes will all run quarter-miles in just under 11 sec onds, on the right track with the right rider. If that rider is Jay Gleason, 130 pounds of pure talent, those times are quicker yet. Gleason has set all the low10-second quarter mile times that you see quoted in motorcycle ads. But this level of performance, once unthinkable, only lead us to speculate: What would it take to get to the next level? What, we asked ourselves, would it take to build a semistreetable motorcycle that would run the quarter-mile in the /?/fie-second bracket?

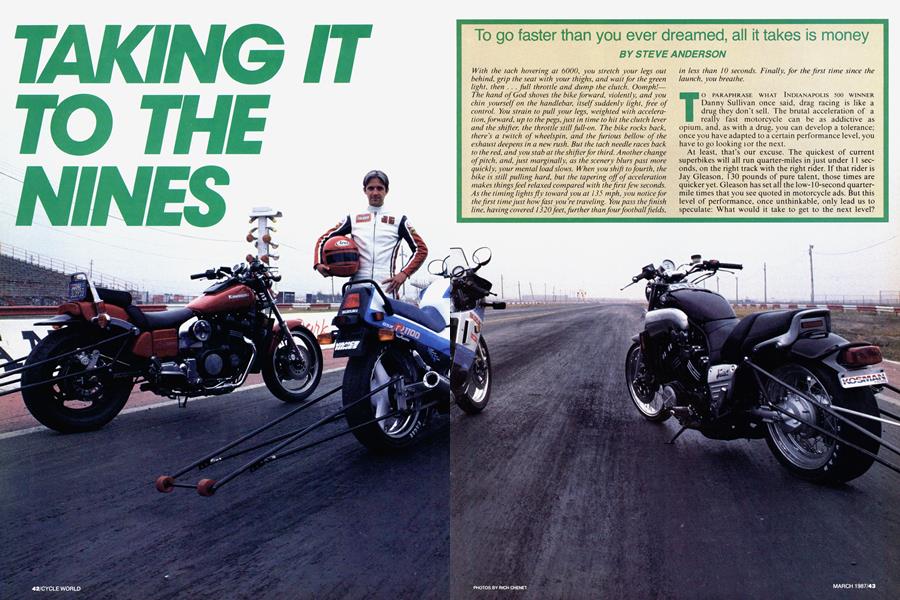

Early 1986: To answer those questions, we start with three motorcycles, a few ideas, and lots of expert help. The first machine chosen is Kawasaki’s 900 Eliminator. With this model, Kawasaki tried to tap into America’s long-held fascination with drag racing by building a motorcycle that looked as if it belonged on the strip. But the Eliminator was more show than go, and never a threat on the track or in the marketplace. So, starting with a standard Eliminator, we aim to build something more like the machine Kawasaki could, and perhaps should, have offered.

The first thing to go is the shaft drive; it’s heavy, and it eliminates the possibility of gearing changes. That’s quite important, for we know that with the other major engine modification we have planned—the addition of a turbocharger—we will have to run taller-than-standard gearing to get the kind of quarter-mile performance we're seeking. So we enlist the aid of Kawasaki's service people, who swap the Eliminator's transmission output shaft and gears for those from a 900 Ninja, and remove the bevel-gear on the left side of the cases to make room for a countershaft sprocket.

That leaves the Eliminator with a chain-drive sprocket on the engine, and a shaft-drive swingarm and rear wheel. So we send the bike to Sandy Kosman of Kosman Specialties, who makes an appropriate swingarm that accepts a 16-inch rear wheel from a Ninja 1000. While he’s at it, he makes the arm a couple of inches longer to further facilitate the bike’s drag-worthiness, and relocates the battery to clear the chain. And for the turbocharger, we turn to the acknowledged master of the art of forced induction, Ted Hofmeister, better-known as Mr. Turbo. He sells no turbo kit specifically for the Eliminator, but modifies his Ninja 900 kit to fit our project bike.

Whatwe end up with isa bike thatan individual couldn’t easily replicate at home; it’s expensive and has a lot of oneoff components. But Kawasaki could conceivably add to

its lineup a refined version of a bike like this—and have a machine that lives up to its Eliminator name.

After the extravagance of modifications that went into the Turbo Eliminator, we resolve to make the next bike—a 1986 V-Max—simpler. Engineers at Yamaha have told us that the V-Max responds readily to exhaustand intakesystem changes, so we turn the bike over to Steve Johnson, head of R&D for Kerker, and tell him to find more power without touching the inside of the engine.

Johnson and his staff remove the V-Max’s airbox and Vboost system, rejet the carbs, and make a very special 4into-2-into-1 pipe, perhaps the most complicated exhaust system Kerker has ever built. The result is a substantial power increase and, with the competition baffle installed, exhaust music unlike that of any other motorcycle. At idle, the Max has the same lumpy, nasty sound of trapped power as a full-race American V-Eight car engine. Accelerating, sometimes it sounds like a Chevy Pro-stocker, sometimes like something else, but never like a motorcycle. Johnson is so enraptured with the V-Max’s song that, during the week that the completed V-Max is awaiting its return to CYCLE WORLD, he often wanders out of his office to the Kerker shop, starts the V-Max and plays the throttle. He always returns to his office smiling.

As important to making the V-Max quick is a new rear wheel and tire combination. Despite the bike having been on the market for two years, no truly sticky tires are available for its 15-inch rear wheel. So again we turn to those master fabricators of the drag-racing world, Kosman Specialties, for an 18-inch spoked-wheel and a wheelie bar. In his enthusiasm for our 9-second project, Sandy Kosman exceeds what is absolutely necessary and installs a spoked front wheel, too, along with his lightweight brake discs and calipers. The end result, wearing pro-stock slicks at both ends, is perhaps the ultimate fantasy stoplight-racer, the machine on which you could best imagine pulling alongside the nastiest, snarliest car on the streets, blipping the throttle once and asking, “Wanna race?”—knowing full well, of course, that there’s no way you’re going to lose.

Our third motorcycle, Suzuki’s GSX-R 1 100, might invoke slightly different fantasies, such as imagining how fast it would go on the banking at Daytona. But this machine has one of the best power-to-weight ratios in motorcycling, along with a short and tall chassis optimized for cornering, not accelerating. We think that with a modest power increase, along with a wheelie bar, a rear slick and

some chassis tuning, it will easily run 9-second quarters.

But when we turn our GSX-R over to Terry Vance and Byron Hines of Vance & Hines Racing for the necessary hot-rodding, we discover that our idea of a “modest” power increase differs slightly from theirs. Using off-theshelf components intended for street use (with the exception of the exhaust silencer), Hines builds an engine that, according to their dyno, raises the GSX-R’s power from a standard 1 1 1 horsepower to a staggering 159. In addition, Hines lowers the bike by replacing the rear shock with a shorter, rigid strut and by shortening the fork. He also adds new wheels front and rear, a rear slick and wheelie bars. So set up, the modified GSX-R threatens to be a drag-racing overdog; it is also Vance & Hines’ first experience with preparing a GSX-R specifically for the strip.

December, 1986: The three bikes are ready, and our choices of rider and track are easy. Jay Gleason, motorcycling’s fastest and most consistent quarter-mile ace, will attempt to crack the 9-second barier at Baylands Raceway in Fremont, California, near San Francisco. Because of its dense, near-sea-level air and outstanding traction, Baylands is a fast track that has been the site of most production-bike record attempts. Observing at the track is an all-star crowd: Sandy Kosman and Peter Anthony of Kosman Specialties; Terry Vance and Byron Hines of Vance & Hines; Kay Nishi, Mark Chapin and George Mamiki from Mikuni American; Mike Wymer from Kerker; and Mark Dobeck of DynoJet Research, the company that assists Kerker in preparing rejetting kits.

First up is the V-Max. Gleason runs down the track twice to familiarize himself with the bike and to warm it up, and then backs it up to the shallow water trough at the beginning of the strip. A quick second-gear burnout, with surprisingly little smoke or tire noise, brings the big Goodyear slick up to operating temperature. Then Gleason rolls the Max forward and stages for his first run.

He launches at only 5000 rpm, causing the bike to bog slightly off the line, but the time still is excellent: 10.03 seconds at 133.92 mph. For the first time, we’re sure that the V-Max will make it into the Nines. For the next run. Jay holds the engine speed at 5800 rpm before dropping the clutch, and the bike fairly leaps away, back hard on the wheelie bar all the way through first gear. When the time pops up on the display board down the strip, everyone at the track is stunned: 9.74 seconds at 135.13 mph. Terry Vance can hardly believe it; he figured the V-Max might run 10-second-flat times at best. Don't forget, this is a heavy motorcycle that’s never had its valve covers off, and that has its tank half full of pump gas, yet it's running fast enough to have whipped a Pro-stock field 12 years ago.

Mark Dobeck of Dynojet thinks the V-Max might run faster yet, so he and Wymer yank its carbs and drop the main jets two sizes. Dobeck feels this will help change the blackish buildup on the silencer’s exit to a more pleasing gray, and boost top-end power. Gleason tries again, and on his second run with the new jetting, turns 9.69 seconds at 135.74 mph. The V-Max is retired, having thoroughly and easily proven its point; of the five runs it has made today, all except the first were well into the Nines.

Next is the Turbo Eliminator. It’s the only bike not wearing a rear slick; no 16-inch slicks intended specifically for drag racing are available, so we set the bike up with a DOT-approved production roadracing tire. We wonder if perhaps this was the wrong choice.

It was. Gleason's initial burnout produces a huge cloud of white smoke, and when he launches, the tire smokes off the line. It continues to spin through second gear, third, even fourth; only when he shifts into fifth far down the strip does the tire howl stop. The time is a slow, 1 1.39 seconds, but the terminal speed an excellent 136 mph.

Gleason reports that the Turbo is a real arm-straightener, pulling even harder in the higher gears than the VMax. But the next runs are the same combination of slow times and fast speeds, all about 10.7 seconds with speeds of around 138 mph. The Eliminator is making enough power to run deep into the Nines, but it won’t get there without a better tire, something not to be found at Baylands today.

So now it’s the GSX-R’s turn. Gleason takes it down the strip for familiarization, and doesn't like it at all. The engine feels great, but the handling doesn’t. Hit a bump at speed and it wobbles. “You wouldn't even want to know what’s it’s doing,’’ says a serious-looking Gleason.

Hines estimates that the bike is too short and light to work without suspension, especially because Baylands isn't all that smooth. But the one thing that isn’t in the truck today is the GSX-R’s stock rear shock. So the next few hours are spent experimenting with fork preload, tire choices, wheelie-bar adjustment, wheelie-bar removal, and even a 750 Suzuki shock (without spring) from Kosman's shop; but nothing works. The bike is intent on wobbling, and Hines, himself recovering from a recent crash in which a wobbling drag bike spit him off, doesn’t even consider asking Gleason to try a run. The bikes will both have their chance, on another day.

One week later, Los Angeles County Raceway: Winter rainstorms in the San Francisco area prevent a return to Baylands, so LACR is our best alternative. But its location in Palmdale, California, 2600 feet above sea level, means that times will be slower here. For record purposes, the NHRA uses a correction factor to translate times at altitude back to sea-level standard conditions; so while we will give the actual times at LACR. we will also note the NHRA-approved corrections.

Vance & Hines has put the stock suspension back on the GSX-R1 100, and a few trips down the track convinces Gleason that its stability has been restored, as well. But the first launch with wheelie bars fitted demonstrates a new problem: Without rigid suspension to control wheelie-bar height, the GSX-R rears back so hard on the bar that it rebounds back forward onto its front tire, which causes it to bounce back onto the bar. For the first 20 feet or so, the GSX-R pogos violently, bouncing back and forth between the front tire and the wheelie bar. Still, the run is fairly quick: 10.36 seconds at 134.94 mph observed, which is a corrected time of 10.03 at 139.5 mph.

We figure that by adjusting the wheelie-bar rollers all the way to the ground, the GSX-R won't pitch back so violently and the pogoing will be stoppped. Our first attempt places them too low, which partially unweights the rear wheel during the launch and causes wheelspin off the line. There’s another side-effect, too: The rollers stay loaded the entire run and, spinning 15,000 rpm by strip’s end. overheat and fly apart. Still, the run was promising: an observed 10.02 seconds at 133.92 mph, which corrects to 9.70 seconds at 138.5 mph.

Time for a few last tweaks on the GSX-R. We fit smaller main jets to compensate for altitude-induced richness, and raise the wheelie bars slightly after fitting a new set of rollers. In this trim, the GSX-R becomes a 9-second quarter-miler beyond dispute: Gleason herds it down the strip in 9.84 seconds at 138.24 mph, numbers that, by NHRA correction, indicate that the GSX-R should run an impres-

sive 9.52 seconds at 142.9 mph at sea level. This roadracer doesn't do badly at the drag strip.

Unfortunately, the Eliminator doesn’t fare so well. A soft-compound 16-inch Michelin roadracing slick gives it needed traction, and on Gleason’s first launch the tire spins only a bit. Jay is conservative this first run, but his time is again promising: an observed 10.06 seconds at 135.74 mph, which corrects to 9.90 seconds and 138.0 mph. (The correction factor is less for turbos than it is for normally aspirated engines because forced-induction engines are affected less by altitude changes.) His next launch is outstanding, but the run is only a disappointing 10.47 seconds at 133.32 mph. The next run tells the story; after another hard launch, the Eliminator starts to lose boost going down the strip. Gleason responds by backing off, and is greeted by seemingly expensive engine sounds.

At this point, the only thing left is to load the truck and head home. For now, at least, the Eliminator is out of commission.

Later, back in the CYCLE WORLD shop, we discover that the Eliminator has spun its No. 3 rod bearing. And we conclude that the failure was probably our fault as much as anything. Mr. Turbo’s Ted Hofmeister had suggested that we re-clearance the rod bearings before running the engine, but we declined to do so, not wanting to further add to the expense of what had already become an absurdly expensive machine. That was, as it turned out, a false economy. Hofmeister also instructed us to put at least 500 easy break-in miles on the engine before applying any serious boost so that the new pistons and rings he had installed could fully seat. But in our haste to get three hot-rodded bikes ready for the strip, we had not heeded his advice once again. That error in judgement resulted in the failure of the rings to seat, explaining the ever-deteriorating times at the strip.

So at least one part of our question is left unanswered— the part dealing with the Eliminator. But we will answer it. The engine is being repaired as this is written; and, weather permitting, we will take the bike back to the strip—with the necessary break-in miles on the engine and the recommended clearance in the bearings—to see what this turbocharged monster will really do, and report on the results in the next month or two. Don't be surprised if the Eliminator posts the quickest times of all three of the bikes. Prostock champ Terry Vance, in fact, after watching the Kawasaki smoke its rear tire most of the way through the strip at Baylands, thought that it might even reach the eights!

So in the end, we can draw a few conclusions from this orgy of acceleration. First, as motorcycles close in on the 9-second barrier, chassis and tire performance can become as important as pure horsepower. Vance agrees, pointing out that a few inches of wheelbase can often be the equivalent of a lot of horses. Wheelie bars help compensate, but they’re racing-only devices.

Second, improving motorcycle dragstrip times much from their current level is expensive. The Kerker pipe and carb kit offer impressive gains for the V-Max engine without great expense, but bringing the V-Max chassis up to snuff is costly. For the GSX-R, Vance & Hines parts give an exceptional power increase, but at a significant cost. Mikuni tells us that an exhaust system and 36mm smoothbores will add over 20 horsepower to a GSXR1100; and that, combined with a sticky tire and a wheelie bar, might be the most effective way to put that bike into the Nines. But even those modifications cost around $1200. A turbocharger, as used by the Eliminator, almost

certainly gives the greatest power increase, but again, it’s expensive. Also, converting the Turbo Eliminator to chain drive was less than cost-efficient; were we to do it again, we would consider using gearing components from a Kawasaki Concours to get the final-drive ratios we needed. That would still leave the problem of where to find either a sticky 15-inch tire, or a larger-diameter wheel that would fit the final drive.

Third, we think there’s something the motorcycle manufacturers can learn from this project. Now that Suzuki has stopped producing the GS1 150, no company offers a motorcycle that is easily adapted to drag racing. The perfect bike would have a big, torquey engine, chain drive, lots of wheelbase, a low center of gravity, not much weight, and a wide, 18-inch rear wheel.

Finally, with all due respect to Danny Sullivan, we learned that drag racing is a drug that money can buy. Riding any one of these three motorcycles at the strip is a rush whose aftereffects linger on. As Jay Gleason put it, grinning in his helmet after his 9.69-second pass on the VMax, “Thanks for the memories.” EE

Kerker Exhaust Systems 7900 Deering Avenue Canoga Park, CA 91304 (818) 999-3060 (800) 423-5246

Kosman Racing 340 Fell St

San Francisco, CA 94102 (415) 861-4262

Mr. Turbo 8002 S. Madison Burr Ridge IL 60521 (312) 986-5669

Vance & Hines Racing Products 14010 Marquardt Santa Fe Springs, CA 90670 (213) 921-7461

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialFear And Loathing In the Doubles

March 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeProliferating Poseurs

March 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1987 -

Cycle World

Cycle WorldSummary

March 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley-Davidson: Trading Motorcycles For Motorhomes?

March 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

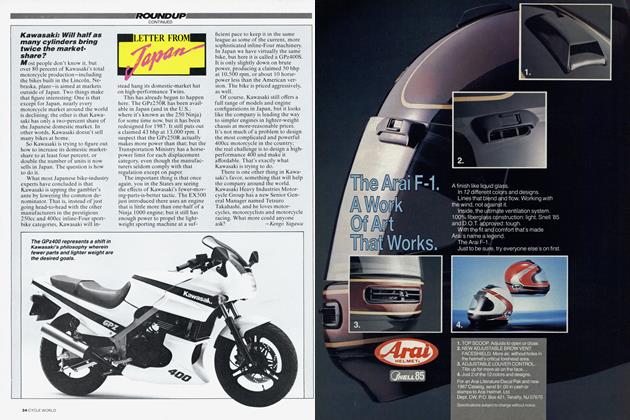

RoundupLetter From Japan

March 1987 By Kengo Yagawa