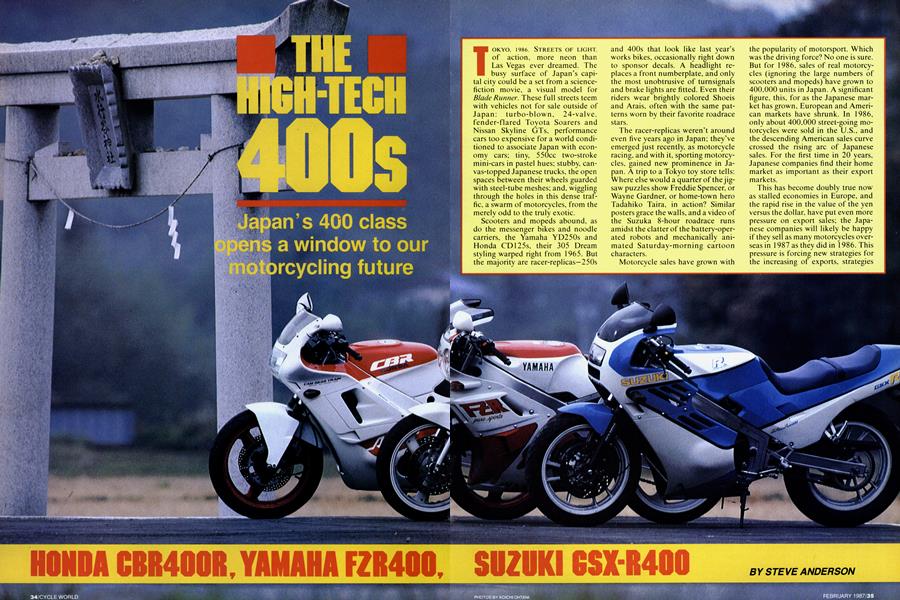

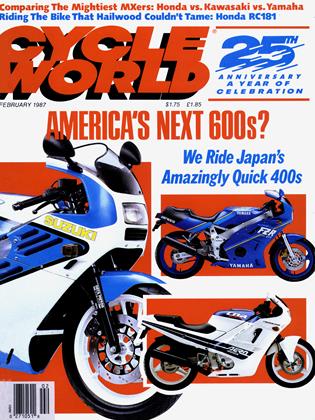

THE HIGH-TECH 400s

Japan's 400 class opens a window to our motorcycling future

HONDA CBR400R, YAMAHA FZR400,

SUZUKI GSX-R400

STEVE ANDERSON

TOKYO, 1986. STREETS OF LIGHT, of action, more neon than Las Vegas ever dreamed. The busy surface of Japan’s capital city could be a set from a science-fiction movie, a visual model for Blade Runner. These full streets teem with vehicles not for sale outside of Japan: turbo-blown, 24-valve, fender-flared Toyota Soarers and Nissan Skyline GTs, performance cars too expensive for a world conditioned to associate Japan with economy cars; tiny, 550cc two-stroke mini-cars in pastel hues; stubby, canvas-topped Japanese trucks, the open spaces between their wheels guarded with steel-tube meshes; and, wiggling through the holes in this dense traffic, a swarm of motorcycles, from the merely odd to the truly exotic. Scooters and mopeds abound, as do the messenger bikes and noodle carriers, the Yamaha YD250s and Honda CD 125s, their 305 Dream styling warped right from 1965. But the majority are racer-replicas—250s and 400s that look like last year’s works bikes, occasionally right down to sponsor decals. A headlight replaces a front numberplate, and only the most unobtrusive of turnsignals and brake lights are fitted. Even their riders wear brightly colored Shoeis and Aráis, often with the same patterns worn by their favorite roadrace stars.

The racer-replicas weren’t around even five years ago in Japan; they’ve emerged just recently, as motorcycle racing, and with it, sporting motorcycles, gained new prominence in Japan. A trip to a Tokyo toy store tells: Where else would a quarter of the jigsaw puzzles show Freddie Spencer, or Wayne Gardner, or home-town hero Tadahiko Taira, in action? Similar posters grace the walls, and a video of the Suzuka 8-hour roadrace runs amidst the clatter of the battery-operated robots and mechanically animated Saturday-morning cartoon characters.

Motorcycle sales have grown with the popularity of motorsport. Which was the driving force? No one is sure. But for 1986, sales of real motorcycles (ignoring the large numbers of scooters and mopeds) have grown to 400,000 units in Japan. A significant figure, this, for as the Japanese market has grown, European and American markets have shrunk. In 1986, only about 400,000 street-going motorcycles were sold in the U.S., and the descending American sales curve crossed the rising arc of Japanese sales. For the first time in 20 years, Japanese companies find their home market as important as their export markets.

This has become doubly true now as stalled economies in Europe, and the rapid rise in the value of the yen versus the dollar, have put even more pressure on export sales; the Japanese companies will likely be happy if they sell as many motorcycles overseas in 1987 as they did in 1986. This pressure is forcing new strategies for the increasing of exports, strategies that generally involve giving customers more value by lowering costs. As a result, the technology wars that have been going on in the 600, 750 and lOOOcc classes will slow noticeably.

But in the increasingly important Japanese home market, that won’t work; the market there is dominated by teenage and early-twenties riders who want the latest and the trickest, and who increasingly have the money to pay for it. Thus, the motorcycle

technology war has found a new home: In Japan, in the 250 and 400cc sportbike classes.

These classes were not chosen because the Japanese necessarily like small bikes; instead, numerous legal and financial strictures have created a strong market for these sizes. A Japanese rider is required, for instance, to have one of three licenses. The first allows its holder to ride mopeds or low-powered 50cc scooters, and is

very easy to obtain. The second-level license is only slightly harder to acquire, and it allows the piloting of machines up to 400cc; this is the license most Japanese riders possess. But many aspire to the top license, the one for all machines over 400cc, and here is where the protective bureaucracy intrudes. The holders of open-class licenses must have passed difficult written and riding performance tests, given under the eyes of examiners who fail far more than they pass. Open-class license holders may have taken the tests 10 or 15 times before passing, and have paid a fee before each test.

This process tests determination at least as much as skill; only two percent of Japanese motorcyclists have persisted long enough to acquire the open-class license. The rest must be content to stay on smaller bikes. Even then, the Japanese government provides strong incentives to think smaller. Purchase tax, insurance and inspection requirements all make 250s cheaper to buy and own than 400s.

So the principal classes of Japanese motorcycling are two: 250cc, with a 45-horsepower limit self-imposed by the manufacturers (but only with the approval and assistance of the government, which must give manufacturers the required approval certificates before they can release a new model for sale), and 400cc, with a similarly self-imposed, 59-horsepower limit.

But what 250s and 400s! The bestselling 250 is the Yamaha TZR twostroke Twin, a replica of Yamaha’s TZ250 racebike, and the first street machine to make use of Yamaha’s GP-style twin-beam “Deltabox” aluminum frame. Honda has just released an NSR250R (an amazingly close replica of Honda’s own RS250 GP bike) to compete with the Yamaha. Four-stroke 250s haven’t been slighted, either: Yamaha introduced a 16,000-rpm, 45-horsepower, 16valve FZ250 Four to an eager Japanese market, only to see Honda counter it within a year with a CBR250R that raised the redline race to 17,000 rpm while also adding an aluminum frame and gear-driven cams to the ante.

If anything, the 400cc class has been even more hotly contested. The first GSX-R (a 400, of course) made its debut in Japan almost three years ago, as did the first FZ400 a few months later, back when the FZ750 was still a rumor in this country. The Ninja 600 had its Japanese firstcousin, the 1985 GPz400, which got an aluminum frame that wasn’t seen in the U.S. until a special edition of the 1986 Ninja 600. Two-strokes such as Suzuki’s RG400 Four and Honda’s NSR400 Triple compete, as well, but haven’t been as popular as their four-stroke brethren. (Perhaps two-stroke 400s suffer because of the popularity of Formula 3 racing in Japan, which pits four-stroke 400s against two-stroke 250s. At a single race, seeing 500 entrants competing for only 40 grid positions is not uncommon.)

The rapid pace of 400-class development allows no pause; though their predecessors were scarcely over two years old, new 400cc inlineFours from Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki appeared in 1986, each a significant improvement over the machine it replaced.

Suzuki’s new 400cc GSX-R, for example, is light like its predecessor, but better-handling and much more polished. Its refined styling mimics the Yoshimura GSX-R750 FI racer that won a Japanese championship, while its engine continues Suzuki’s recent fascination with unusual cooling systems, using a combination of water-, oiland air-cooling. Yamaha’s FZR400 was that company’s first four-stroke to make use of an aluminum Deltabox frame (fabricated from sheet metal and castings), and brings the “Genesis” engine technology to the 400 class. Honda’s CBR400R pulls out all the stops with an aluminum frame, gear-driven cams, and inclined cylinders with downdraft carburetion.

All three are said to make 59 horsepower, the same number claimed for their predecessors, but not all horsepowers are created equal; the current horses are bigger than those of the recent past. The GSX-R400, for instance, will run mid-12-second quarter-miles, as fast or faster than any U.S. 600 we’ve tested.

But of more interest to American riders is the close relationship that often exists between Japanese 400s and U.S. 600s: More and more, the 600s simply have been enlarged 400s, appearing a year or so after their smaller parents. The FZ600 is nothing but an FJ600 motor shoehorned into an FZ400 chassis; and even Honda’s new CBR600 Hurricane is closely related to the CBR400R that first appeared in Japan last spring.

In Honda’s case, however, the 600 is the down-price model; while it has the same body panels as the 400, its engine is a modified design that shares only the 400’s outer shape, and not its gear-driven cams. And while the 400 uses an aluminum frame, the CBR600 makes do with steel.

It’s simply a question of money. The CBR400 costs around $4200 in Japan, while the 600 is offered for $3700 in the U.S. According to Honda, $200 of that difference is due to the aluminum frame; at least some of the rest is owed to the differing cam drives.

Of the various conclusions that can be drawn from this, some are disturbing. Is it possible, for instance, that the U.S. or Europe can no longer afford Japan’s best motorcycle technology? Honda’s CBR series seems to answer “yes” to that question. The CBR250, 400 and soon-to-be-released 750 all make use of aluminum frames and gear-driven cams, and all are aimed most directly at the Japanese home market (the 2 percent of Japanese motorcyclists with openclass licenses buy a healthy number of 750s). The CBR600 and 1000 make do with cam chains and steel frames, but they’re intended for the U.S. and Europe, not for Japan.

Another viewpoint is to look at the 400s as an alternative to our 750s and 1000s, which, through one law or another, are denied to 98 percent of Japanese motorcyclists. From this vantage, more-advanced—and moreexpensive—technology tries to compensate for the simpler advantages of larger displacement. That explains why the 400s perform as well as some larger machines, and are also too expensive to fit neatly into product lineups in the U.S. or Europe; even the 250 Fours sell for almost $3500 in Japan. So don’t expect any of the most sophisticated Japanese sportbikes to find their way overseas to America.

In any case, it appears we can’t have new technology quite as soon as the Japanese. That’s no reason to despair; technological change comes so fast anyway that it hardly matters if a given feature appears this year or the next. But it’s every reason to follow what goes on in the Japanese market, particularly in the 400 class, the current hothouse of motorcycle development. Because what they have this year, we’ll undoubtedly have very, very soon.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialSeoul-Searching

February 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1987 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

February 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupWill Japan's Cure For A Stagnant Market Work In America?

February 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupWhen School Is Meant To Be A Drag

February 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Entry-Level Sportbike: Destined For America?

February 1987 By Koichi Hirose