AT LARGE

Duck Soup

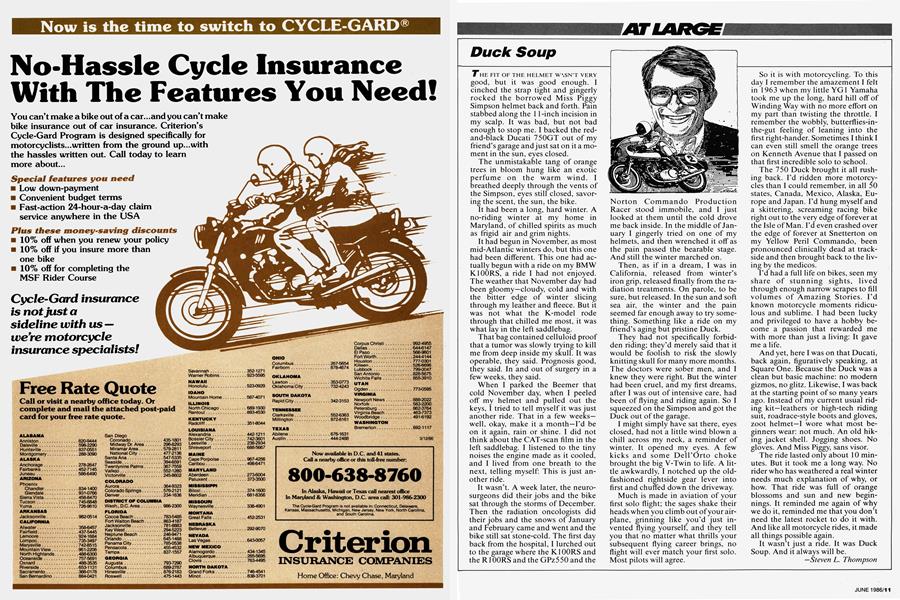

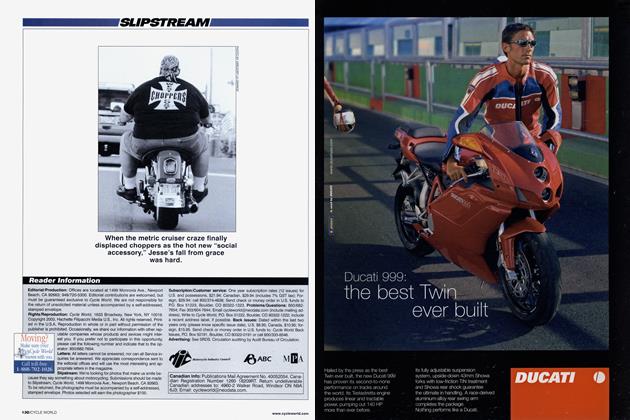

THE FIT OF THE HELMET WASN’T VERY good, but it was good enough. I cinched the strap tight and gingerly rocked the borrowed Miss Piggy Simpson helmet back and forth. Pain stabbed along the 11-inch incision in my scalp. It was bad, but not bad enough to stop me. I backed the red-and-black Ducati 750GT out of my friend’s garage and just sat on it a moment in the sun, eyes closed.

The unmistakable tang of orange trees in bloom hung like an exotic perfume on the warm wind. I breathed deeply through the vents of the Simpson, eyes still closed, savoring the scent, the sun, the bike.

It had been a long, hard winter. A no-riding winter at my home in Maryland, of chilled spirits as much as frigid air and grim nights.

It had begun in November, as most mid-Atlantic winters do, but this one had been different. This one had actually begun with a ride on my BMW K100RS, a ride I had not enjoyed. The weather that November day had been gloomy—cloudy, cold and with the bitter edge of winter slicing through my leather and fleece. But it was not what the K-model rode through that chilled me most, it was what lay in the left saddlebag.

That bag contained celluloid proof that a tumor was slowly trying to kill me from deep inside my skull. It was operable, they said. Prognosis good, they said. In and out of surgery in a few weeks, they said.

When I parked the Beemer that cold November day, when I peeled off my helmet and pulled out the keys, I tried to tell myself it was just another ride. That in a few weeks— well, okay, make it a month—I’d be on it again, rain or shine. I did not think about the CAT-scan film in the left saddlebag. I listened to the tiny noises the engine made as it cooled, and I lived from one breath to the next, telling myself: This is just another ride.

It wasn’t. A week later, the neurosurgeons did their jobs and the bike sat through the storms of December. Then the radiation oncologists did their jobs and the snows of January and February came and went and the bike still sat stone-cold. The first day back from the hospital, I lurched out to the garage where the K100RS and the R1OORS and the GPz550 and the Norton Commando Production Racer stood immobile, and I just looked at them until the cold drove me back inside. In the middle of January I gingerly tried on one of my helmets, and then wrenched it off as the pain passed the bearable stage. And still the winter marched on.

Then, as if in a dream, I was in California, released from winter’s iron grip, released finally from the radiation treatments. On parole, to be sure, but released. In the sun and soft sea air, the winter and the pain seemed far enough away to try something. Something like a ride on my friend’s aging but pristine Duck.

They had not specifically forbidden riding; they’d merely said that it would be foolish to risk the slowly knitting skull for many more months. The doctors were sober men, and I knew they were right. But the winter had been cruel, and my first dreams, after I was out of intensive care, had been of flying and riding again. So I squeezed on the Simpson and got the Duck out of the garage.

I might simply have sat there, eyes closed, had not a little wind blown a chill across my neck, a reminder of winter. It opened my eyes. A few kicks and some Dell’Orto choke brought the big V-Twin to life. A little awkwardly, I notched up the oldfashioned rightside gear lever into first and chuffed down the driveway.

Much is made in aviation of your first solo flight; the sages shake their heads when you climb out of your airplane, grinning like you’d just invented flying yourself, and they tell you that no matter what thrills your subsequent flying career brings, no flight will ever match your first solo. Most pilots will agree.

So it is with motorcycling. To this day I remember the amazement I felt in 1963 when my little YG1 Yamaha took me up the long, hard hill off of Winding Way with no more effort on my part than twisting the throttle. I remember the wobbly, butterflies-inthe-gut feeling of leaning into the first right-hander. Sometimes I think I can even still smell the orange trees on Kenneth Avenue that I passed on that first incredible solo to school.

The 750 Duck brought it all rushing back. I’d ridden more motorcycles than I could remember, in all 50 states, Canada, Mexico, Alaska, Europe and Japan. I’d hung myself and a skittering, screaming racing bike right out to the very edge of forever at the Isle of Man. I’d even crashed over the edge of forever at Snetterton on my Yellow Peril Commando, been pronounced clinically dead at trackside and then brought back to the living by the medicos.

I’d had a full life on bikes, seen my share of stunning sights, lived through enough narrow scrapes to fill volumes of Amazing Stories. I’d known motorcycle moments ridiculous and sublime. I had been lucky and privileged to have a hobby become a passion that rewarded me with more than just a living: It gave me a life.

And yet, here I was on that Ducati, back again, figuratively speaking, at Square One. Because the Duck was a clean but basic machine: no modern gizmos, no glitz. Likewise, I was back at the starting point of so many years ago. Instead of my current usual riding kit—leathers or high-tech riding suit, roadrace-style boots and gloves, zoot helmet—I wore what most beginners wear: not much. An old hiking jacket shell. Jogging shoes. No gloves. And Miss Piggy, sans visor.

The ride lasted only about 10 minutes. But it took me a long way. No rider who has weathered a real winter needs much explanation of why, or how. That ride was full of orange blossoms and sun and new beginnings. It reminded me again of why we do it, reminded me that you don’t need the latest rocket to do it with. And like all motorcycle rides, it made all things possible again.

It wasn’t just a ride. It was Duck Soup. And it always will be.

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue