ROUNDUP

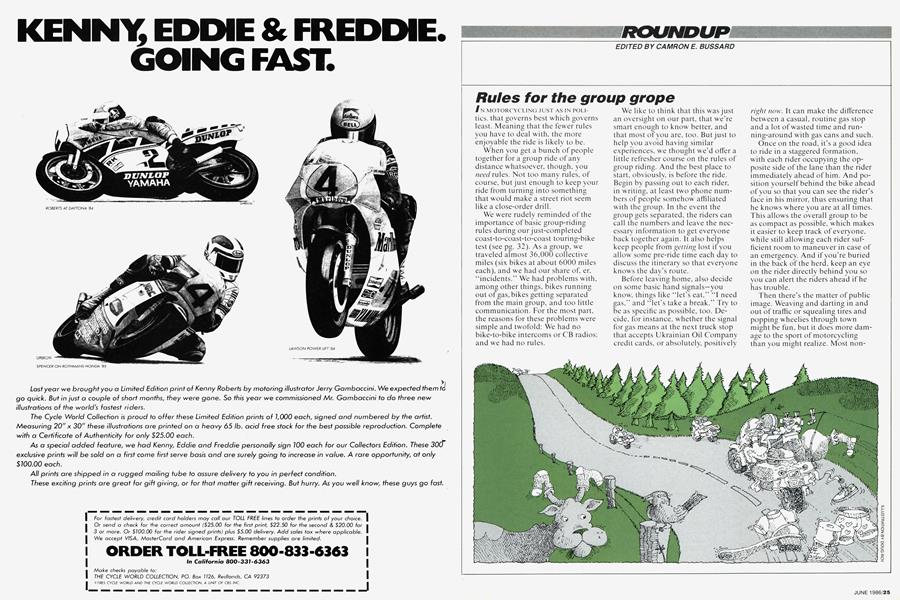

Rules for the group grope

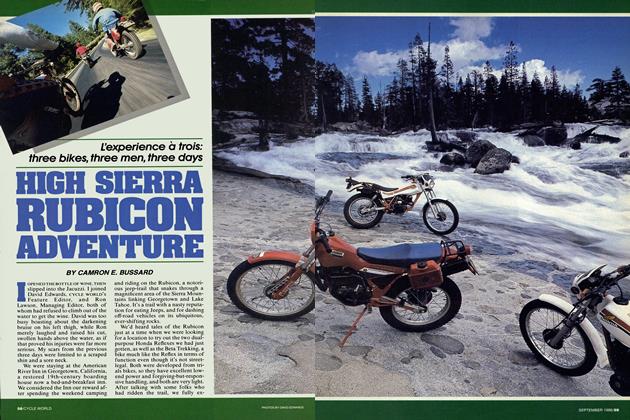

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

IN MOTORCYCLING JUST AS IN POLItics, that governs best which governs least. Meaning that the fewer rules you have to deal with, the more enjoyable the ride is likely to be.

When you get a bunch of people together for a group ride of any distance whatsoever, though, you need rules. Not too many rules, of course, but just enough to keep your ride from turning into something that would make a street riot seem like a close-order drill.

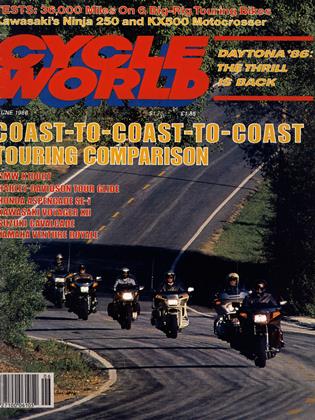

We were rudely reminded of the importance of basic group-riding rules during our just-completed coast-to-coast-to-coast touring-bike test (see pg. 32). As a group, we traveled almost 36,000 collective miles (six bikes at about 6000 miles each), and we had our share of, er, “incidents.” We had problems with, among other things, bikes running out of gas, bikes getting separated from the main group, and too little communication. For the most part, the reasons for these problems were simple and twofold: We had no bike-to-bike intercoms or CB radios; and we had no rules.

We like to think that this was just an oversight on our part, that we're smart enough to know better, and that most of you are, too. But just to help you avoid having similar experiences, we thought we’d offer a little refresher course on the rules of group riding. And the best place to start, obviously, is before the ride. Begin by passing out to each rider, in writing, at least two phone numbers of people somehow affiliated with the group. In the event the group gets separated, the riders can call the numbers and leave the necessary information to get everyone back together again. It also helps keep people from getting lost if you allow some pre-ride time each day to discuss the itinerary so that everyone knows the day’s route.

Before leaving home, also decide on some basic hand signals—you know, things like “let’s eat,” “I need gas,” and “let’s take a break.” Try to be as specific as possible, too. Decide, for instance, whether the signal for gas means at the next truck stop that accepts Ukrainian Oil Company credit cards, or absolutely, positively right now. It can make the difference between a casual, routine gas stop and a lot of wasted time and running-around with gas cans and such.

Once on the road, it’s a good idea to ride in a staggered formation, with each rider occupying the opposite side of the lane than the rider immediately ahead of him. And position yourself behind the bike ahead of you so that you can see the rider’s face in his mirror, thus ensuring that he knows where you are at all times. This allows the overall group to be as compact as possible, which makes it easier to keep track of everyone, while still allowing each rider sufficient room to maneuver in case of an emergency. And if you're buried in the back of the herd, keep an eye on the rider directly behind you so you can alert the riders ahead if he has trouble.

Then there’s the matter of public image. Weaving and darting in and out of traffic or squealing tires and popping wheelies through town might be fun, but it does more damage to the sport of motorcycling than you might realize. Most nonriding people usually shrug off such antics when only one bike is involved, but they can’t help but be outraged when they see a dozen riders acting up at once. So remember that in a large group, you have a much greater impact on the people who see you. Make that impact positive, not negative.

Now, so far, this has all been pretty serious stuff that most of you probably already knew. But we’ll bet that there are a few other useful laws and principles of group rides that you are not aware of. For example, there’s Griewe’s First Law, established by Senior Editor Ron Griewe, which states that for every person added to a group of any size, the stops will take twice as long. Griewe attributes this to what he calls “the flounder factor.” A gas stop that takes 1 5 minutes for three people will take 30 minutes for four; lunch stops with really large groups could take days. There's also Griewe’s Second Law, which is, simply stated:

It’s never too late to make the turn. Griewe demonstrated this principle several times while leading the group, leaving behind a trail of sparks and flying rubber as he darted onto an off-ramp or around a corner despite having already passed it.

Law Three is the expansion principle. Dirty shorts and smelly socks take up more space than clean shorts and freshly washed socks, so you have to allow room when you pack for clothes expansion.

Law Four is, never pass an open gas station in west Texas. Sub-section “a” of Law Four is, avoid Fort Stockton, Texas, even if the gas stations are open and in the midst of a price war.

Law Five: If you want it to rain at any point during the trip, wash your bike; if you want it to stop raining, put on your rainsuit. The latter part of this law extends from the theory that no matter what type of riding gear you put on, it will always be wrong.

Law Six is a strong suggestion rather than an iron-clad rule: It is best not to play Twisted Sister on your tape deck while riding through small towns in Mississippi. Carry at least one Merle Haggard cassette to get you safely to the city limits.

And finally, there's Rule Seven, which many of us think should be Law One: If your route includes any state other than California, don't leave home without your radar detector. Ever.

Of course, none of these “suggestions” are etched in stone. What’s important is to have some way to watch out for one another. And if your group has a system that works better than ours, by all means use it. Just don’t let the rules get in the way of the ride. Finding the delicate balance between too many and not enough rules isn’t easy, but it pays off in the end.

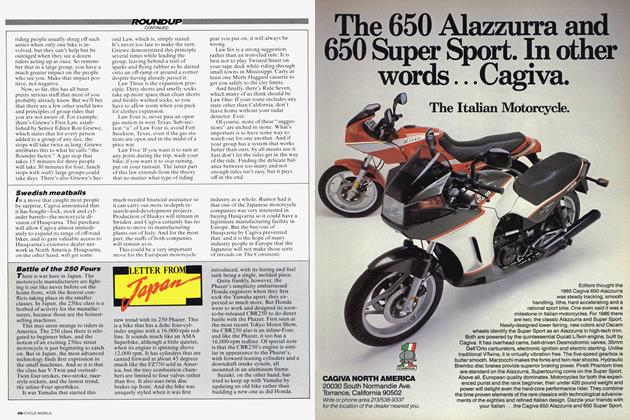

Swedish meatballs

In a move that caught most people by surprise, Cagiva announced that it has bought—lock, stock and cylinder barrels—the motorcycle division of Husqvarna. This purchase will allow Cagiva almost immediately to expand its range of off-road bikes, and to gain valuable access to Husqvarna’s extensive dealer network in North America. Husqvarna, on the other hand, will get some much-needed financial assistance so it can carry out more in-depth research-and-development projects. Production of Huskys will remain in Sweden, and Cagiva certainly has no plans to move its manufacturing plants out of Italy. And for the most part, the staffs of both companies will remain as-is.

This could be a very important move for the European motorcycle

industry as a whole. Rumor had it that one of the Japanese motorcycle companies was very interested in buying Husqvarna so it could have a legitimate manufacturing facility in Europe. But the buy-out of Husqvarna by Cagiva prevented that; and it is the hope of many industry people in Europe that the Japanese will not make those sorts of inroads on The Continent.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue