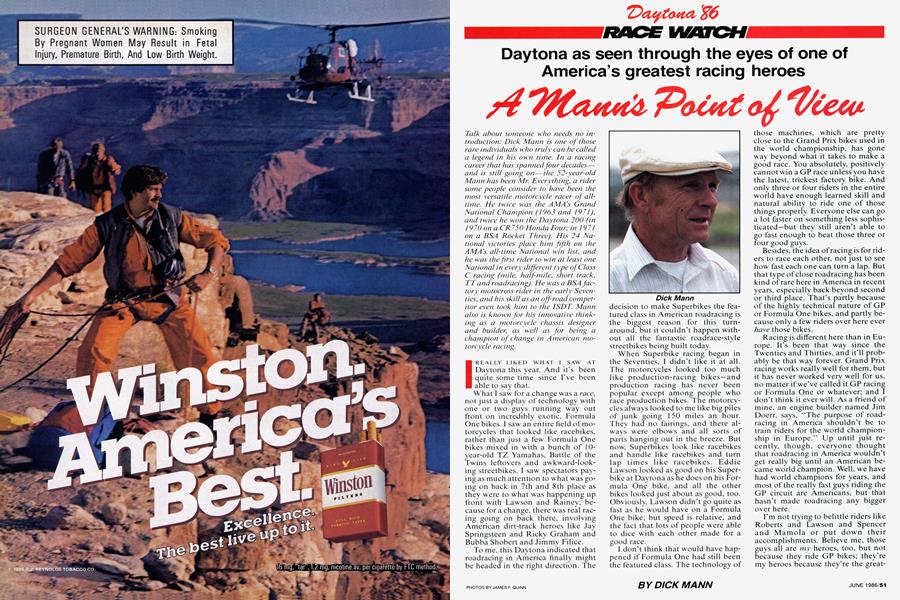

A Mann's Point of View

RACE WATCH

Daytona '86

Daytona as seen through the eyes of one of America’s greatest racing heroes

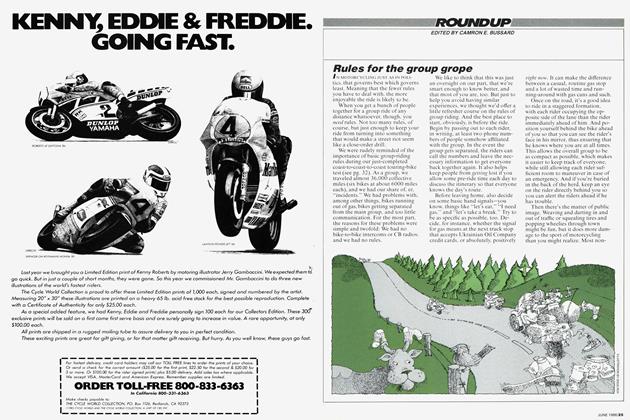

Talk about someone who needs no introduction: Dick Mann is one of those rare individuals who truly can be called a legend in his own time. Ina racing career that has spanned four decades— and is still going on—the 52-year-old Mann has been Mr. Everything, a rider some people consider to have been the most versatile motorcycle racer of alltime. He twice was the AMA's Grand National Champion (1963 and 1971), and twice he won the Daytona 200 (in 1970 on a CR750 Honda Four; in 1971 on a BSA Rocket Three). His 24 National victories place him fifth on the AMA's all-time National win list, and he was the first rider to win at least one National in every different t ype of Class C racing (mile, half-mile, short track, TT and roadracing). He was a BSA factory motocross rider in the early Seventies, and his skill as an offroad competitor even took him to the ISDT. Mann also is known for his innovative thinking as a motorcycle chassis designer and builder, as well as for being a champion of change in American motorcycle racing.

I REALLY LIKED WHAT I SAW AT Daytona this year. And it’s been quite some time since I’ve been able to say that.

What I saw for a change was a race, not just a display of technology with one or two guys running way out front on incredibly exotic, Formula One bikes. I saw an entire field of motorcycles that looked like racebikes, rather than just a few Formula One bikes mixed in with a bunch of 10-year-old TZ Yamahas, Battle of the Twins leftovers and awkward-looking streetbikes. I saw spectators paying as much attention to what was going on back in 7th and 8th place as they were to what was happening up front with Lawson and Rainey; because for a change, there was real racing going on back there, involving American dirt-track heroes like Jay Springsteen and Ricky Graham and Bubba Shobert and Jimmy Filice.

To me, this Daytona indicated that roadracing in America finally might be headed in the right direction. The decision to make Superbikes the featured class in American roadracing is the biggest reason for this turnaround, but it couldn’t happen without all the fantastic roadrace-style streetbikes being built today.

When Superbike racing began in the Seventies, I didn’t like it at all. The motorcycles looked too much like production-racing bikes—and production racing has never been popular except among people who race production bikes. The motorcycles always looked to me like big piles of junk going 150 miles an hour. They had no fairings, and there always were elbows and all sorts of parts hanging out in the breeze. But now. Superbikes look like racebikes and handle like racebikes and turn lap times like racebikes. Eddie Lawson looked as good on his Superbike at Daytona as he does on his Formula One bike, and all the other bikes looked just about as good, too. Obviously, Lawson didn’t go quite as fast as he would have on a Formula One bike; but speed is relative, and the fact that lots of people were able to dice with each other made for a good race.

I don’t think that would have happened if Formula One had still been the featured class. The technology of those machines, which are pretty close to the Grand Prix bikes used in the world championship, has gone way beyond what it takes to make a good race. You absolutely, positively cannot win a GP race unless you have the latest, trickest factory bike. And only three or four riders in the entire world have enough learned skill and natural ability to ride one of those things properly. Everyone else can go a lot faster on something less sophisticated—but they still aren’t able to go fast enough to beat those three or four good guys.

Besides, the idea of racing is for riders to race each other, not just to see how fast each one can turn a lap. But that type of close roadracing has been kind of rare here in America in recent years, especially back beyond second or third place. That’s partly because of the highly technical nature of GP or Formula One bikes, and partly because only a few riders over here ever have those bikes.

Racing is different here than in Europe. It’s been that way since the Twenties and Thirties, and it'll probably be that way forever. Grand Prix racing works really well for them, but it has never worked very well for us, no matter if we’ve called it GP racing or Formula One or whatever; and I don’t think it ever will. As a friend of mine, an engine builder named Jim Doerr, says, “The purpose of roadracing in America shouldn’t be to train riders for the world championship in Europe.” Up until just recently, though, everyone thought that roadracing in America wouldn't get really big until an American became world champion. Well, we have had world champions for years, and most of the really fast guys riding the GP circuit are Americans, but that hasn’t made roadracing any bigger over here.

I’m not trying to belittle riders like Roberts and Lawson and Spencer and Mamola or put down their accomplishments. Believe me, those guys all are my heroes, too, but not because they ride GP bikes; they’re my heroes because they’re the greatest riders in the world, guys who are so much better than everyone else that it’s almost not fair to put them on the same track with the other riders. But that still hasn’t helped roadracing grow in America.

DICK MANN

As far as I’m concerned, that happened because we kept trying to do roadracing the European way. But now, some Europeans are thinking about trying our way. Kenny Roberts went over there and won the championship with a riding style that involved a lot of sliding around, almost like you do on a dirt track; and since then, most of the fast GP riders have been ex-dirt-track racers from America. So a lot of Europeans now believe that the only way to win the world championship on the GP circuit is to come to America and learn how to ride dirt track.

That’s really ironic. Back when I was racing, we Class C riders knew what was going on with racing in the rest of the world, and we thought we were pretty low-class. The Europeans seemed to have so much style and tradition, and we didn’t. For us, the emphasis was on the race. We were just interested in beating the other guy around the turn. Everybody just did whatever it took or used whatever style needed to get the job done. But that made for good racing, with lots of riders really mixing it up with their elbows stuck in each others’ armpits.

That was the U.S. style of dirttrack racing, and it spread over into the U.S. style of roadracing back then, too. But now that Americans who come from that type of racing are dominating the world championship, I think maybe we weren’t as unsophisticated as we thought we were.

Anyway, that sort of close racing throughout the entire field is what America likes. I’m not saying that’s the only thing American racing fans care about; the whole thing won’t work unless all of the big heroes are out there, too. But if there’s some good, hard racing going on, up front and throughout the rest of the field, and if the motorcycles everyone is riding really look like racebikes, the fans won’t care whether or not the superstars are riding the trickest, most technical GP bikes imaginable.

That’s why I think the Superbikes can be such good things. They’re sophisticated enough that the heroes can ride them and look good on them and have really close racing; and at the same time, they make reasonably competitive, reasonably affordable racing possible once again for so many people who aren't big heroes.

Twenty years ago, back when Class C racing was really going strong, most sponsorships came from individual dealers and tuners, not from the factories. But as factories got more and more involved and roadracing in America gradually became so much like European GP racing, it got harder and harder for dealers and people at that level to maintain their enthusiasm for that kind of competition. They couldn’t buy or build a real GP bike, and couldn’t have afforded one, anyway. So they either had to drop out of roadracing or else put something on the track—like a modified production-class streetbike or an old, out-of-date roadracer—that was almost an embarrassment. But this new formula allows them to start with a really trick streetbike that’s sitting on their showroom floor and put something on the track that looks and sounds and feels just like what the winner is riding. I think that will encourage a lot more dealers and tuners to get involved in Superbike racing.

Judging by the size of the field at Daytona this year, it has already started to happen. I spent a couple of days walking around in what I call “the trenches”—those open-sided garages in the pits that are used by the real privateers who work out of the backs of their vans—and those guys were really hard at work. A couple of years ago, you’d find most of the riders and mechanics down there laughing and horsing around, not taking the whole thing very seriously. Most had come for some other event— maybe the Battle of the Twins or the Friday Superbike race—and being in Sunday’s Formula One race was just an add-on giggle. But not this year; just like always, those guys knew that they had no chance to actually win, but they were dead-serious anyway. They were there to race.

If you want to give the credit for this to someone, give it to Bill France of Daytona Speedway. Making the Superbikes the main event was his doing, not the AMA’s or anyone else’s. France told the AMA last year that the featured class at Daytona was going to be the Superbikes, whether they liked it or not. The AMA almost had to give in, and their Superbike rules grew out of the need to accommodate Daytona. But I think France was 100-percent right. I have great respect for him, because he has not made any mistakes in the racing game, not that I’ve seen, anyway. His NASCAR stock-car racing program is the most long-lived and consistently successful form of racing in the world, and it just keeps getting bigger and better. He knows what it takes to make for good racing and keep the fans happy.

Actually, if anyone has made a mistake, it’s the AMA. They decided to have separate points and championships for roadracing and dirttrack, beginning this year; but considering the new appeal of the Superbike class, that might have been an untimely move. If National roadraces still offered championship points for dirt-trackers, you’d have at least 10 more of the top dirt guys at every one of them. With current Superbike rules, those guys could be fairly competitive, maybe pick up a few points, and not look like fools on stupid motorcycles. That’s a real strong incentive for them to compete.

Some people say that the factories will always have the edge, that the money they spend will always give them an advantage over everyone else. And I guess that’s true. There’s never absolute equality in racing. But as long as the rules only allow bikes that are based on production engines, the factories won't have the ridiculous advantage they do in GP racing. And we can again have roadracing that’s based on one rider simply trying to get around the corner faster than another.

I think that’s what American fans want. I also think Bill France’s idea is going to give it to them.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue