THE PERFECT FAMILY TREE

Honda’s new VFR750 ought to be good. Its parents are world champions.

ALAN CATHCART

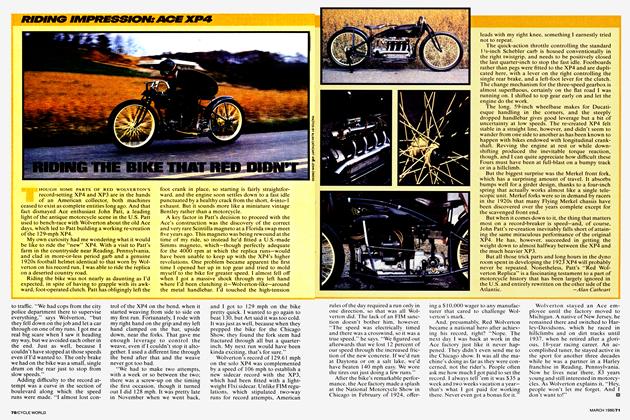

GOOD BREEDING. THEY SAY, tells. And if that is so, the new Honda VFR750F road bike may well be in for a charmed life. The racebike from which it is derived, you see, is one of the most impressive pieces of racetrack hardware ever.

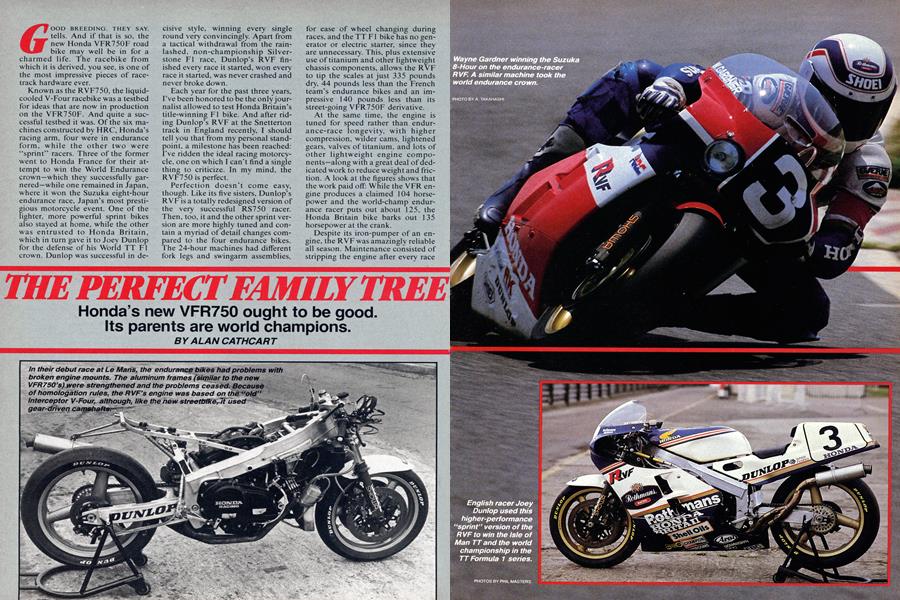

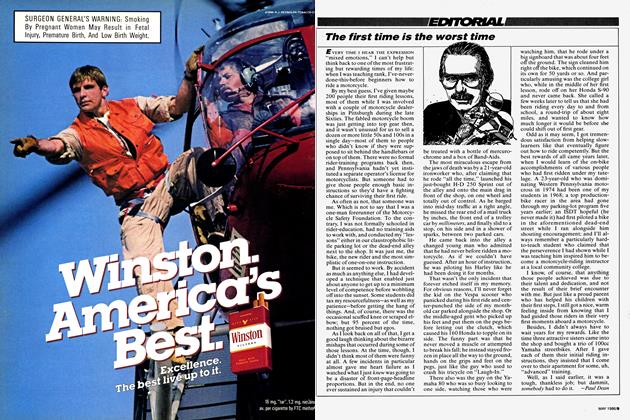

Known as the RVF750, the liquidcooled V-Four racebike was a testbed for ideas that are now in production on the VFR750F. And quite a successful testbed it was. Of the six machines constructed by HRC, Honda’s racing arm, four were in endurance form, while the other two were “sprint” racers. Three of the former went to Honda France for their attempt to win the World Endurance crown-which they successfully garnered-while one remained in Japan, where it won the Suzuka eight-hour endurance race, Japan’s most prestigious motorcycle event. One of the lighter, more powerful sprint bikes also stayed at home, while the other was entrusted to Honda Britain, which in turn gave it to Joey Dunlop for the defense of his World TT F1 crown. Dunlop was successful in decisive style, winning every single round very convincingly. Apart from a tactical withdrawal from the rainlashed, non-championship Silverstone FI race, Dunlop’s RVF finished every race it started, won every race it started, was never crashed and never broke down.

Each year for the past three years, I’ve been honored to be the only journalist allowed to test Honda Britain’s title-winning FI bike. And after riding Dunlop’s RVF at the Snetterton track in England recently, I should tell you that from my personal standpoint, a milestone has been reached: I’ve ridden the ideal racing motorcycle, one on which I can't find a single thing to criticize. In my mind, the RVF750 is perfect.

Perfection doesn’t come easy, though. Like its five sisters, Dunlop’s RVF is a totally redesigned version of the very successful RS750 racer. Then, too, it and the other sprint version are more highly tuned and contain a myriad of detail changes compared to the four endurance bikes. The 24-hour machines had different fork legs and swingarm assemblies, for ease of wheel changing during races, and the TT FI bike has no generator or electric starter, since they are unnecessary. This, plus extensive use of titanium and other lightweight chassis components, allows the RVF to tip the scales at just 335 pounds dry, 44 pounds less than the French team’s endurance bikes and an impressive 140 pounds less than its street-going VFR750F derivative.

At the same time, the engine is tuned for speed rather than endurance-race longevity, with higher compression, wilder cams, lightened gears, valves of titanium, and lots of other lightweight engine components—along with a great deal of dedicated work to reduce weight and friction. A look at the figures shows that the work paid off: While the VFR engine produces a claimed 104 horsepower and the world-champ endurance racer puts out about 125, the Honda Britain bike barks out 135 horsepower at the crank.

Despite its iron-pumper of an engine, the RVF was amazingly reliable all season. Maintenance consisted of stripping the engine after every race for inspection, but the only parts needed all season were just one set of exhaust valves as a precautionary measure. The engine has a 70mm bore, a 48.6mm stroke, and a 360degree crankshaft as in the .past, rather than the 180-degree crank of the new VFR750 engine; the 1986 racer will, however, have the 180-degree crank.

Like the road bike, the RVF750 uses an aluminum, beam-type frame that lowers the engine location, and therefore the whole bike, by doing away with the lower frame rails. The bluff-fronted fairing, developed after extensive wind-tunnel tests, helps achieve the reduced frontal area Honda desired, and a rider like Joey Dunlop can just about tuck himself away behind that low, flat screen. I couldn’t, but I still felt comfortable on the bike in spite of being a good bit taller than its normal rider.

Comfortable? More than happy would be a better description. I couldn’t believe how easy it was to flick the bike from side to side or to change its direction. HRC’s designers may have lowered the weight to improve air penetration, but they also made the motorcycle ultra-responsive as a result.

The fact is that the RVF is a truly effortless racing motorcycle. There really isn’t a powerband as such; just notch bottom gear on the right-foot, one-up-four-down, five-speed gearbox, feed out the clutch, and off you go—just like a road bike but much, much more quickly. The engine drives from zero rpm, with heaps of torque available almost all the way through the revband. There’s a noticeable amount of extra urge from 9500 rpm upwards, and below 6000 revs the power falls off a bit. So all you’ve got left to play with if you’re Joey Dunlop is 5500 revs. Gee, it's tough being a works Honda rider.

This mile-wide powerband, which has none of the old RS750 racer’s flat spots or peakiness, means you can rev the bike 1000 rpm below its safe limit, as Dunlop does, and shift gears when it suits you rather than when the engine and tach tell you to, allowing you to concentrate on getting the rest of your riding right. And the new chassis permits you to get the most out of that lovely, torquey engine, for it steers like nothing on earth I’ve ever ridden, at least. Unlike last year’s RS, which I felt carried its engine too far rearward in the frame, this bike is ideally balanced, with positive steering into a corner.

Another plus is the suppleness of the suspension. No matter what the track surface, the suspension refuses to freeze up; so if you seek out the rough stuff on the very inside of a corner where the cars have given the asphalt a pounding, the Honda still follows along the chosen line without chattering at either end. And at the front, most noticeable was the bike’s superb behavior in fast sweepers; It just sat there, glued to the line I’d selected for it, allowing me to crank over farther and corner faster than anything I had ever before ridden on that track. I broke my own personal Snetterton lap record by almost two seconds, which tells you how much I felt at home on the Honda—even compared to the 500cc GP bikes that I've ridden there in the past.

Indeed, everything about the RVF reeks of perfection, from the ultrawide powerband to the unlimited torque; from the neutral steering to the effective braking; from the feather-light controls to the ideal weight distribution. Maybe I can best quantify its attributes by noting some of the things it doesn't do—like sit up under braking, or fall into a corner like so many of today's 16-inchwheeled GP bikes do, or pull wheelies under acceleration, or wash out the front end in fast corners, or mandate that you constantly row the gear lever to stay in the powerband, or weave the front end in a straight line, or chatter the rear end under braking.

The RVF750 is guilty of none of those transgressions, one or more of which is done by every one of its many rivals-whether factory, aftermarket or privateer-developed— that I’ve had the chance to test over the past few years. The RVF750 is perfection in a racing motorcycle, and if Honda really has managed to transfer the qualities of its all-conquering racebike to the new range of VFR streetbikes, I can only say that it won't only be Honda that emerges the winner, but Joe Public, as well. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue