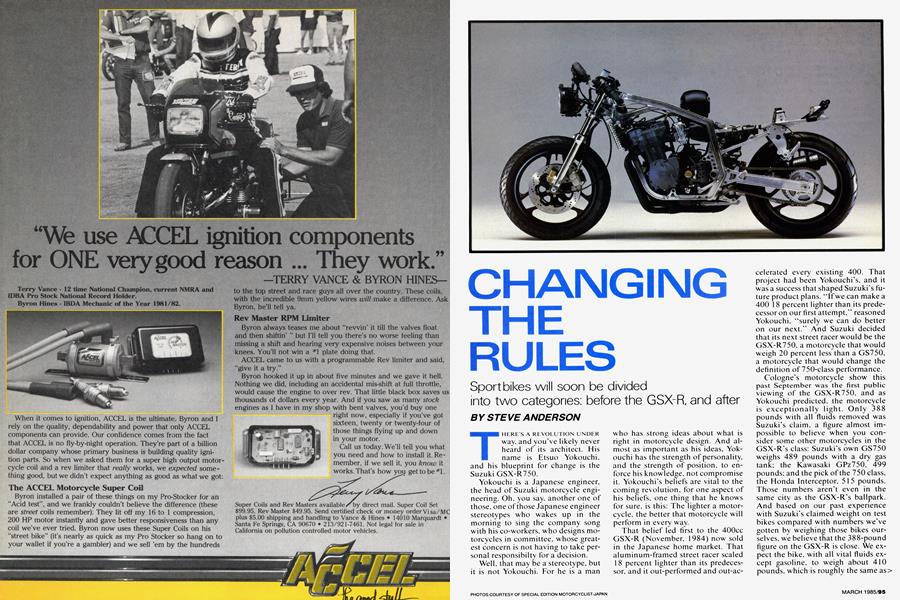

CHANGING THE RULES

Sport bikes will soon be divided into two categories: before the GSX-R, and after

STEVE ANDERSON

THERE'S A REVOLUTION UNDER way, and you've likely never heard of its architect. His name is Etsuo Yokouchi, and his blueprint for change is the Suzuki GSX-R750.

Yokouchi is a Japanese engineer, the head of Suzuki motorcycle engineering. Oh, you say, another one of those, one of those Japanese engineer stereotypes who wakes up in the morning to sing the company song with his co-workers, who designs motorcycles in committee, whose greatest concern is not having to take personal responsibilty for a decision.

Well, that may be a stereotype, but it is not Yokouchi. For he is a man who has strong ideas about what is right in motorcycle design. And almost as important as his ideas, Yokouchi has the strength of personality, and the strength of position, to enforce his knowledge, not compromise it. Yokouchi’s beliefs are vital to the coming revolution, for one aspect of his beliefs, one thing that he knows for sure, is this: The lighter a motorcycle. the better that motorcycle will perform in every way.

That belief led first to the 400cc GSX-R (November, 1984) now sold in the Japanese home market. That aluminum-framed street racer scaled 18 percent lighter than its predecessor, and it out-performed and out-accelerated every existing 400. That project had been Yokouchi's, and it was a success that shaped Suzuki’s future product plans. “If we can make a 400 1 8 percent lighter than its predecessor on our first attempt,” reasoned Yokouchi, “surely we can do better on our next.” And Suzuki decided that its next street racer would be the GSX-R750, a motorcycle that would weigh 20 percent less than a GS750, a motorcycle that would change the definition of 750-class performance.

Cologne’s motorcycle show this past September was the first public viewing of the GSX-R750, and as Yokouchi predicted, the motorcycle is exceptionally light. Only 388 pounds with all fluids removed was Suzuki's claim, a figure almost impossible to believe when you consider some other motorcycles in the GSX-R’s class: Suzuki’s own GS750 weighs 489 pounds with a dry gas tank: the Kawasaki GPz750, 499 pounds: and the pick of the 750 class, the Honda Interceptor, 515 pounds. Those numbers aren’t even in the same city as the GSX-R’s ballpark. And based on our past experience with Suzuki’s claimed weight on test bikes compared with numbers we’ve gotten by weighing those bikes ourselves, we believe that the 388-pound figure on the GSX-R is close. We expect the bike, with all vital fluids except gasoline, to weigh about 410 pounds, which is roughly the same as Honda's classic CB400F, and 105 pounds less than a VF750F.

That 105-pound difference will do more to increase the performance of a 750 than would adding another 250cc. Acceleration depends on more than just power; how much weight that power must move is vital, a notion usually expressed by the machine’s power-to-weight ratio. An Interceptor 750 carrying a 160-pound rider must push 7.8 pounds with each horsepower. An FJ 1 100 has a ratio near 5.5 pounds per horsepower. The GSX-R's ratio should be about 5.7 pounds per horsepower, which will make it a closer match for a strong 1 100 than for a 750. And that lends credibility to Suzuki's hopes for a 10second ET from the GSX-R.

Despite what should be a quantum jump in performance, the GSX-R750 hasn’t sprung from any radically new technology. Quite the reverse, the bike is the product of refinements and adaptions, all of which exist in the current state of the art (but not necessarily the motorcycle art), their use driven by the will of Yokouchi.

According to the engineers working under Yokouchi’s direction, the hardest task of the entire project was achieving the weight goal at the same time as the power goal. For it wasn’t enough just to build the lightest 750. No, Suzuki wanted the GSX-R to be a knockout punch, a motorcycle that could single-handedly give Suzuki the kind of performance image that it was lacking in the European market. That meant 100 horsepower, which is all that is allowed in several European countries. But even that wasn’t enough. Suzuki also wanted to race the GSX-R; and for it to be competitive, adequate strength and cooling to support a reliable 130 horsepower had to be provided.

Conflict between the weight and the power requirements led to the first deviation from standard motorcycle practice. Conventional aircooling becomes more difficult as power density increases, and can lead to hot spots, high oil temperatures and the loss of reliability. But the obvious alternative, liquid-cooling, often has a weight penalty, one that Suzuki figured would amount to 14 pounds. Something else was required.

Suzuki found that something else by looking closely at a non-motorcycle technology—specifically, aircraft piston engines, some of which use oil jets to cool hot spots. Actually, even Suzuki's own 650 Turbo had employed oil jets to assist in piston cooling. Perhaps, reasoned Yokouchi, streams of oil could be used to cool the cylinder-head crown as well. So test engines were built, and they demonstrated that sufficient cooling effect could indeed be achieved.

In the most current GSX-R750 design, the airspace and the fins between the cams typically found on an air-cooled engine are missing. Instead, a single cover tops the entire cylinder head, with deep holes provided for the sparkplugs. Under that cover, there’s an open chamber that leaves cams, valves and combustionchamber crowns all exposed, with only the sparkplug tunnels projecting upward. Tubes almost an eighth ofan inch in diameter direct oil down on the tops of the combustion chambers.

The amount of oil that flows in this system is tremendous. At peak rates, almost 10 liters per minute smash against each combustion-chamber crown; that’s almost as much oil-flow through the GSX-R top end as waterflow through a TZ750 roadrace engine. If that much oil were allowed to splash indiscriminately about the cylinder head and drain back down the cam-chain tunnel, large churning and pumping losses would result. But much of Suzuki's work in designing this oil-assisted cooling system was in finding a combination of sheet-metal baffles and external drain hoses so oil could return to the sump without tangling with fast-spinning parts.

Notice that this cooling system was described as only oil-assisted. Oil pulls heat away from the critical engine hot spots: the cylinder head and piston crowns. The hot oil is then rid of its heat by an oil cooler that has more than four times the cooling capacity of most motorcycle units. But it’s still the finning on cylinders and head that dissipates the bulk of engine heat. And even those fins have been touched by Suzuki’s study of aircraft engines. The close-pitch finning on the GSX-R could be straight from a WWII-era Pratt and Whitney radial. Suzuki found the improved cooling offered by this type of fin reason enough to upgrade the factory’s casting technology to produce it.

Horsepower requirements dictated more than cooling-system design, however; the entire inside of the engine was reshaped to produce power reliably without excess weight. Computerized stress-analysis allowed unnecessary material to be removed from crankcase, pistons and rods. And the weight lost from reciprocating components reduced bearing loads, allowing smaller main and rod bearings to be used. Smaller bearings have correspondingly smaller frictional losses, in this case to the tune of three horsepower at 1 1.000 rpm. But most of the power gains came from more time-honored hot-rod techniques: longer-duration cams, bigger valves, straighter intake tracts and improved combustion chambers. In the end, Suzuki achieved its 100horsepower goal without substantially compromising powerband width, and Yokouchi says happily that there's more to be had from the GSX-R engine when needed.

Compared to its GS750 counterpart, the GSX-R engine weighs 24 pounds less. That figure is slightly less impressive when you learn that l l pounds of the weight reduction is caused by the 4-into-l exhaust system. But that is typical of the GSX-R: Weight has been pared from every part possible, and if the marketing department objected to using a 4-into-1 exhaust, well, they weren't able to override Yokouchi’s will to have his motorcycle be exceptionally light.

It was that will and Suzuki’s manufacturing advances, rather than the use of exotic materials, that have made the GSX-R the featherweight that it is. The only magnesium to be found is in the cylinder-head cover, which might save a few ounces at best. Far more important are advances in foundry arts and stress analysis that make possible pieces such as the GSX-R's aluminum wheels, which have the thinnest spokes we've seen on a full-scale streetbike, or the attention paid to such small details as the single, twochambered reservoir that supplies fluid to the front brake and the clutch master cylinder.

Along with the many subtly light components, there is one that is dramatically light: the GSX-R's l8pound aluminum frame. It's revolutionary not in itself, for aluminum frames have been used before, but instead in its production cost. Other manufacturers look at the GSX-R, note the aluminum chassis and racy bits, and breathe a sigh of relief, thinking that Suzuki has just built a cost-no-object race replica. They’re sighing too soon, because Suzuki has been building aluminum frames for several years now, and has learned how to do it without having to price the finished product like a spare for a GP racer. Suzuki has made use of the ability to incorporate aluminum castings along with extruded tubes to cut the number of parts needed to make an aluminum frame—from 96 parts on a steel-framed 750 to 26 on the GSX-R. The engineers have also developed a proprietary aluminum alloy that performs well in the aswelded condition, eliminating the need for a final heat treatment. All in all, Suzuki has managed to produce an aluminum frame that, compared to a steel frame, will raise the price of the GSX-R less than $ 100.

Still, the GSX-R won't be an inexpensive bike; it will surely be over $4000 in the U.S. regardless of whether it comes in as a 700 or 750 (a matter currently under debate at Suzuki). But that price is more a reflection of the GSX-R’s high-performance capabilities than an indication of Suzuki's manufacturing cost. What is important is that the GSX-R should prove that there is nothing inherently cost-prohibitive in building a light-weight motorcycle.

That’s the real reason the GSX-R will redefine sporting motorcycles. Always before, when manufacturers talked about building a light motorcycle, they were describing a bike that was only 10 or 20 pounds under its competition—not enough to make a significant difference. But the GSXR, if it is delivered as claimed, will be 70 to 100 pounds lighter. With that, Mr. Yokouchi will have been the driving force behind a motorcycle that not only devastates its 750cc competition, but also wreaks havoc on llOOcc sportbikes, motorcycles assumed to be safely out of the GSXR’s territory.

If that indeed comes to pass, every other sportbike will be rendered obsolete. And engineers at other companies will spend the months thereafter recalling fondly what it was like before the GSX-R came along—back when they only worked 10-hour days.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialA Matter of Opinion

March 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1985 -

Departments

DepartmentsSummary

March 1985 -

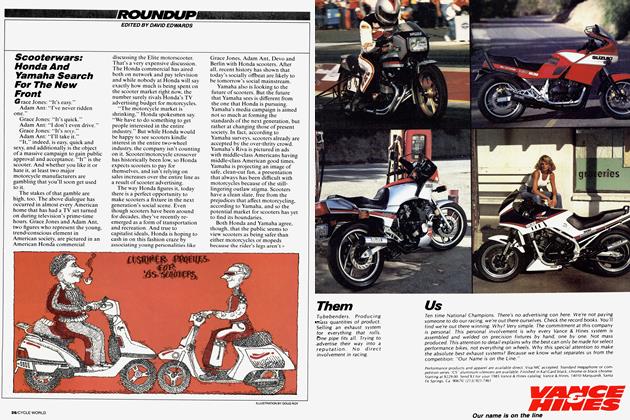

Roundup

RoundupScooterwars: Honda And Yamaha Search For the New Front

March 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupThe $590 Million Engine Rebuild

March 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThree-Wheeling, British-Style

March 1985