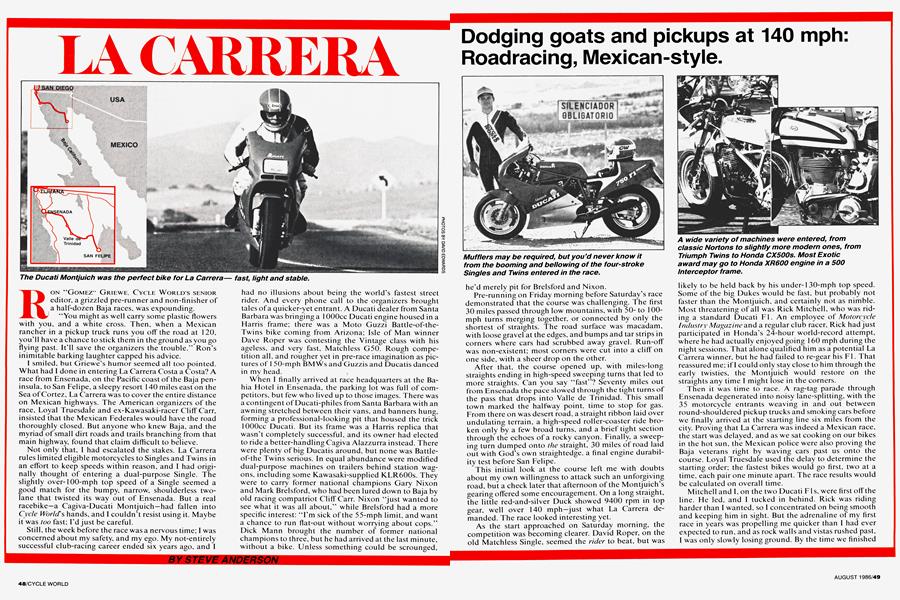

LA CARRERA

RON "GOMEZ" GRIEWE, CYCLE WORLD'S SENIOR editor, a grizzled pre-runner and non-finisher of a half-dozen Baja races, was expounding. "You might as well carry some plastic flowers with you, and a white cross. Then, when a Mexican rancher in a pickup truck runs you off the road at 120, you'll have a chance to stick them in the ground as you go flying past. It'll save the organizers the trouble." Ron's inimitable barking laughter capped his advice.

I smiled, but Griewe’s humor seemed all too pointed. What had I done in entering La Carrera Costa a Costa? A race from Ensenada, on the Pacific coast of the Baja peninsula, to San Felipe, a sleepy resort 140 miles east on the Sea of Cortez, La Carrera was to cover the entire distance on Mexican highways. The American organizers of the race, Loyal Truesdale and ex-Kawasaki-racer Cliff Carr, insisted that the Mexican Federales would have the road thoroughly closed. But anyone who knew Baja, and the myriad of small dirt roads and trails branching from that main highway, found that claim difficult to believe.

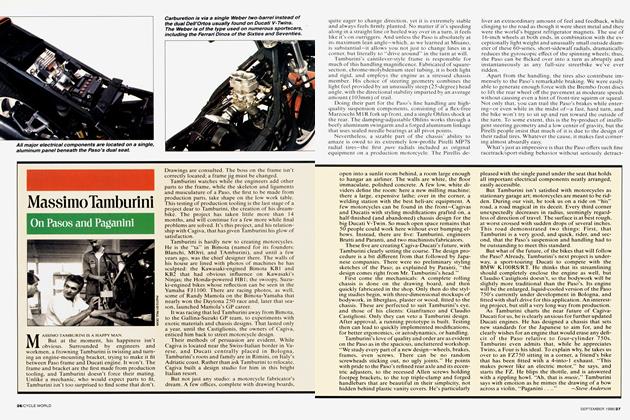

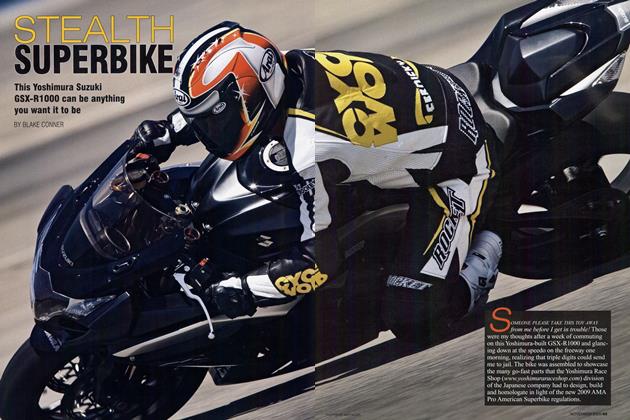

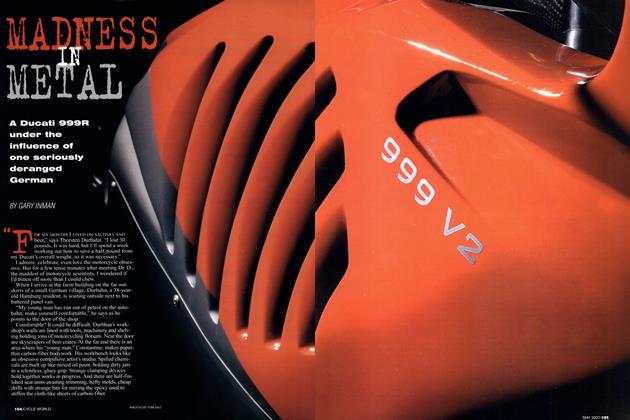

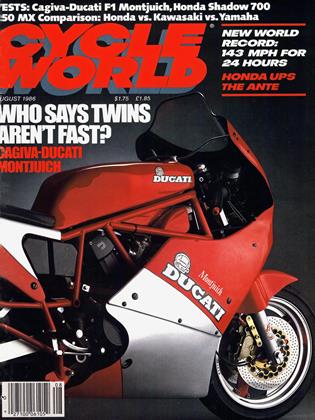

Not only that, I had escalated the stakes. La Carrera rules limited eligible motorcycles to Singles and Twins in an effort to keep speeds within reason, and I had originally thought of entering a dual-purpose Single. The slightly over-100-mph top speed of a Single seemed a good match for the bumpy, narrow, shoulderless twolane that twisted its way out of Ensenada. But a real racebike—a Cagiva-Ducati Montjuich—had fallen into Cycle Worlds hands, and I couldn’t resist using it. Maybe it was too fast; I’d just be careful.

Still, the week before the race was a nervous time; I was concerned about my safety, and my ego. My not-entirely successful club-racing career ended six years ago, and I

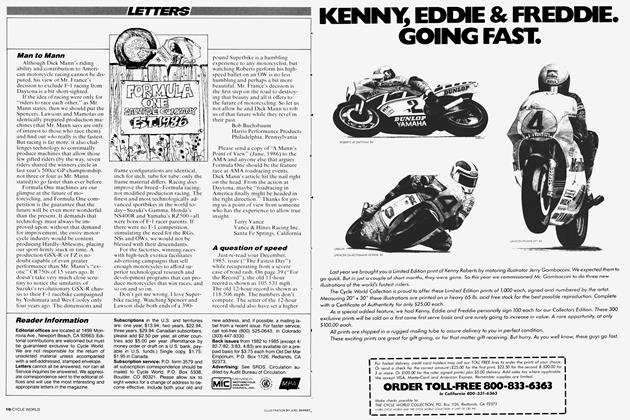

had no illusions about being the world’s fastest street rider. And every phone call to the organizers brought tales of a quicker-yet entrant. A Ducati dealer from Santa Barbara was bringing a 1 OOOcc Ducati engine housed in a Harris frame; there was a Moto Guzzi Battle-of-theTwins bike coming from Arizona; Isle of Man winner Dave Roper was contesting the Vintage class with his ageless, and very fast, Matchless G50. Rough competition all, and rougher yet in pre-race imagination as pictures of 1 50-mph BMWs and Guzzis and Ducatis danced in my head.

When 1 finally arrived at race headquarters at the Bahia Hotel in Ensenada, the parking lot was full of competitors, but few who lived up to those images. There was a contingent of Ducati-philes from Santa Barbara with an awning stretched between their vans, and banners hung, forming a professional-looking pit that housed the trick 1 OOOcc Ducati. But its frame was a Harris replica that wasn’t completely successful, and its owner had elected to ride a better-handling Cagiva Alazzurra instead. There were plenty of big Ducatis around, but none was Battleof-the Twins serious. In equal abundance were modified dual-purpose machines on trailers behind station wagons, including some Kawasaki-supplied KLR600s. They were to carry former national champions Gary Nixon and Mark Brelsford, who had been lured down to Baja by old racing compatriot Cliff Carr. Nixon “just wanted to see what it was all about,” while Brelsford had a more specific interest: “I’m sick of the 55-mph limit, and want a chance to run flat-out without worrying about cops.” Dick Mann brought the number of former national champions to three, but he had arrived at the last minute, without a bike. Unless something could be scrounged,

STEAVE ANDERSON

Dodging goats and pickups at 140 mph: Roadracing, Mexican-style.

he’d merely pit for Breisford and Nixon.

Pre-running on Friday morning before Saturday’s race demonstrated that the course was challenging. The first 30 miles passed through low mountains, with 50to 100mph turns merging together, or connected by only the shortest of straights. The road surface was macadam, with loose gravel at the edges, and bumps and tar strips in corners where cars had scrubbed away gravel. Run-off was non-existent; most corners were cut into a cliff on one side, with a sheer drop on the other.

After that, the course opened up, with miles-long straights ending in high-speed sweeping turns that led to more straights. Can you say “fast”? Seventy miles out from Ensenada the pace slowed through the tight turns of the pass that drops into Valle de Trinidad. This small town marked the halfway point, time to stop for gas. From there on was desert road, a straight ribbon laid over undulating terrain, a high-speed roller-coaster ride broken only by a few broad turns, and a brief tight section through the echoes of a rocky canyon. Finally, a sweeping turn dumped onto the straight, 30 miles of road laid out with God’s own straightedge, a final engine durability test before San Felipe.

This initial look at the course left me with doubts about my own willingness to attack such an unforgiving road, but a check later that afternoon of the Montjuich's gearing offered some encouragement. On a long straight, the little red-and-silver Duck showed 9400 rpm in top gear, well over 140 mph—just what La Carrera demanded. The race looked interesting yet.

As the start approached on Saturday morning, the competition was becoming clearer. David Roper, on the old Matchless Single, seemed the rider to beat, but was

likely to be held back by his under-1 30-mph top speed. Some of the big Dukes would be fast, but probably not faster than the Montjuich, and certainly not as nimble. Most threatening of all was Rick Mitchell, who was riding a standard Ducati FI. An employee of Motorcycle Industry Magazine and a regular club racer, Rick had just participated in Honda’s 24-hour world-record attempt, where he had actually enjoyed going 160 mph during the night sessions. That alone qualified him as a potential La Carrera winner, but he had failed to re-gear his FI. That reassured me; if I could only stay close to him through the early twisties, the Montjuich would restore on the straights any time I might lose in the corners.

Then it was time to race. A rag-tag parade through Ensenada degenerated into noisy lane-splitting, with the 35 motorcycle entrants weaving in and out between round-shouldered pickup trucks and smoking cars before we finally arrived at the starting line six miles from the city. Proving that La Carrera was indeed a Mexican race, the start was delayed, and as we sat cooking on our bikes in the hot sun, the Mexican police were also proving the Baja veterans right by waving cars past us onto the course. Loyal Truesdale used the delay to determine the starting order; the fastest bikes would go first, two at a time, each pair one minute apart. The race results would be calculated on overall time.

Mitchell and I, on the two Ducati F l s, were first off the line. He led, and I tucked in behind. Rick was riding harder than I wanted, so I concentrated on being smooth and keeping him in sight. But the adrenaline of my first race in years was propelling me quicker than I had ever expected to run, and as rock walls and vistas rushed past, I was only slowly losing ground. By the time we finished

with the tight corners, I was down only 30 or 40 seconds; soon, the long straights allowed the Montjuich to reel in Mitchell, putting me into the lead. A perfect gas stop, executed by Cycle World shop foreman Dave Pedersen, enlarged that lead, and I was left with enjoying the ride and trying not to do anything stupid.

The rest of the ride was hardly boring. Small, dark shapes far down the road on one straight resolved themselves into a herd of goats, forcing a drop to a near walking pace before the bellow of the Montjuich chased them away. And the vados—long dips where economical Mexican highway engineers dropped the road to sandwash level instead of building a bridge that would be required only during the rainy season—were equally interesting. On one of the more abrupt drops, at over 140 mph, the Montjuich suddenly went light, and the engine’s song shot up an octave; I was still in a tuck when we landed 100 feet farther down the road, softly, fortunately, and with the front wheel straight. I can honestly say there was no fear; there wasn’t time. I did, however, roll the throttle back for later vados.

More danger was presented by cars and trucks on the course; closing speeds for the vehicles we were passing approached 80 mph, and 200 mph for the oncoming traffic. Fortunately, there were no accidents, even if David Roper did come close; he rounded a corner to find not one but two pickup trucks taking up the road. He squeaked by on the far right edge before the passing truck could move back over.

My Montjuich crossed the finish line first, having taken 1 hour, 17 minutes and 4 seconds to cover 140.4 miles, a 109-mph average. Mitchell came across two minutes later, for second place. Later, after the times were tabulated, David Roper finished third overall, both first vintage and first 500, with a 1:20:27; Fred Eiker, a regular Battle-of-the-Twins competitor, managed a fourth, ahead of all the big Ducatis, in 1:21:21 on a Norton 850. Eiker may have put in the ride of the race; his Norton had run out of gas once, forcing him to coast into his gas stop.

But for most of the entrants, this race wasn’t about winning. It was about blasting down roads as fast as you cared to go, without worrying about the police. It was about the bench-racing in the pits and after the race, and the chance to hear about Mark Brelsford’s eventful pit stop, where he was doused with a crotchful of gasoline. (This planned pit stop led to a second, impromptu, stop to allow Brelsford to dispose of his gasoline-logged underwear. Other La Carrera competitors reported seeing a strange, naked man dancing in obvious pain by the roadside). It was about the party afterward in San Felipe.

But for me, La Carrera was a Ducati Montjuich singing sharply at over 9000 rpm, a song so sweet I hated to roll off the throttle for the turns. It was flying over vados at 140, and zipping past cars at twice or three times their speed. And it sure didn’t hurt to win. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue