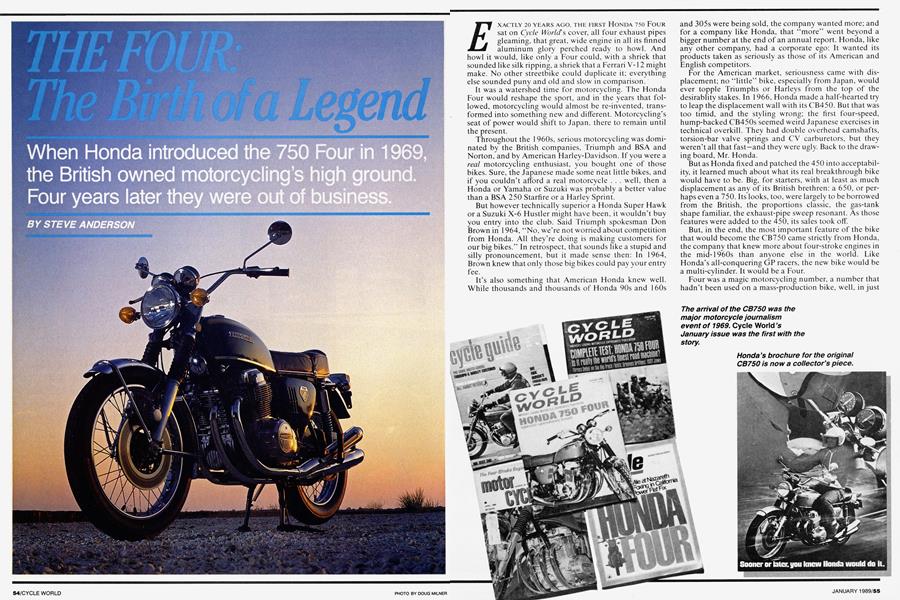

THE FOUR: The Birth of a Legend

When Honda introduced the 750 Four in 1969, the British owned motorcycling's high ground. Four years later they were out of business

STEVE ANDERSON

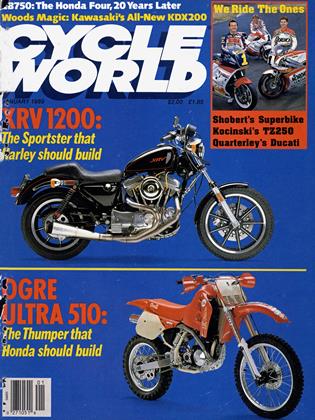

EXACTLY 20 YEARS AGO, THE FIRST HONDA 750 FOUR sat on Cycle World's cover, all four exhaust pipes gleaming, that great, wide engine in all its finned aluminum glory perched ready to howl. And howl it would, like only a Four could, with a shriek that sounded like silk ripping, a shriek that a Ferrari V-12 might make. No other streetbike could duplicate it; everything else sounded puny and old and slow in comparison.

It was a watershed time for motorcycling. The Honda Four would reshape the sport, and in the years that followed, motorcycling would almost be re-invented, transformed into something new and different. Motorcycling’s seat of power would shift to Japan, there to remain until the present.

Throughout the 1960s, serious motorcycling was dominated by the British companies, Triumph and BSA and Norton, and by American Harley-Davidson. If you were a real motorcycling enthusiast, you bought one of those bikes. Sure, the Japanese made some neat little bikes, and if you couldn’t afford a real motorcycle . . . well, then a Honda or Yamaha or Suzuki was probably a better value than a BSA 250 Starfire or a Harley Sprint.

But however technically superior a Honda Super Hawk or a Suzuki X-6 Hustler might have been, it wouldn’t buy you entry into the club. Said Triumph spokesman Don Brown in 1964, “No, we’re not worried about competition from Honda. All they’re doing is making customers for our big bikes.” In retrospect, that sounds like a stupid and silly pronouncement, but it made sense then: In 1964, Brown knew that only those big bikes could pay your entry fee.

It’s also something that American Honda knew well. While thousands and thousands of Honda 90s and 160s and 305s were being sold, the company wanted more; and for a company like Honda, that “more” went beyond a bigger number at the end of an annual report. Honda, like any other company, had a corporate ego: It wanted its products taken as seriously as those of its American and English competitors.

For the American market, seriousness came with displacement; no “little” bike, especially from Japan, would ever topple Triumphs or Harleys from the top of the desirablity stakes. In 1966, Honda made a half-hearted try to leap the displacement wall with its CB450. But that was too timid, and the styling wrong; the first four-speed, hump-backed CB450s seemed weird Japanese exercises in technical overkill. They had double overhead camshafts, torsion-bar valve springs and CV carburetors, but they weren’t all that fast—and they were ugly. Back to the drawing board, Mr. Honda.

But as Honda fixed and patched the 450 into acceptability, it learned much about what its real breakthrough bike would have to be. Big, for starters, with at least as much displacement as any of its British brethren: a 650, or perhaps even a 750. Its looks, too, were largely to be borrowed from the British, the proportions classic, the gas-tank shape familiar, the exhaust-pipe sweep resonant. As those features were added to the 450, its sales took off.

But, in the end, the most important feature of the bike that would become the CB750 came strictly from Honda, the company that knew more about four-stroke engines in the mid-1960s than anyone else in the world. Like Honda’s all-conquering GP racers, the new bike would be a multi-cylinder. It would be a Four.

Four was a magic motorcycling number, a number that hadn’t been used on a mass-production bike, well, in just about forever. It was a number reserved for low-volume bikes with long-gone or rarely seen names, bikes like the Hendersons and Indians and Ariels that had become things to collect rather than to ride. It was a number reserved for Italian racing bikes, the Güeras and MV Agustas that had dominated the 500 GP class for more than a decade. It was a number reserved for Honda’s own GP bikes, bikes that didn’t begin making power to well past a Triumph’s rev limit, and then continued on for another 10,000 rpm. But with the CB750, Honda would reserve that magic number for you, so long as you had the necessary $ 1495.

But beyond the numerology, the 750 Four didn’t owe all that much in detail to Honda’s GP machines. The similarity of that bike first shown on the January, 1969, Cycle World cover to a Honda GP racer pretty much began and ended with the cylinder count. The many differences stemmed from a common theme: Low cost could be obtained only through simplicity. If the goal were to build an affordable 750, 1960s racing technology was

inappropriate.

Thus, nowhere inside the 750 were there features such as roller-bearing crankshafts, double overhead camshafts and four-valve cylinder heads. Instead, the engine had as straightforward an architecture as possible. At its foundation was a one-piece, forged-steel crankshaft carrying an alternator at one end, ignition points at the other. It spun on plain bearings just like any Detroit automotive engine. Rising above the crank was a one-piece, aluminum cylinder block with pressed-in iron liners. Unlike the racing engines, the 750’s bores, at 61mm, were decidely smaller than its 63mm strokes. This undersquare bore/stroke ratio reduced cylinder width at the expense of ultra-high-rpm capability, although the 8500-rpm redline of the 750 was high for its day. Finally, the cylinders were crowned with a simple, two-valve cylinder head, a hemi-head arrangement with a single camshaft opening its valves through rocker arms.

The only real complexity in the engine came in power transmission. A roller chain took power off the center of the crankshaft back to the clutch, and from there to a very Japanese-traditional countershaft transmission. But with the engine spinning the same direction as the wheels, the power sprocket had to run on an additional transmission shaft for proper power flow.

Time alters perspective; by current standards the Honda’s 750 engine seems bulky, simple and not very powerful. Honda claimed only 67 horsepower, and dyno tests measured numbers in the mid-50s. Such figures would be embarrassingly low for a current 600, but in 1969, they were a revolution. The original Honda 750 would yank the heart out of any British bike of the era, with the possible exception of the BSA/Triumph Triples and the Norton Combat Commando.

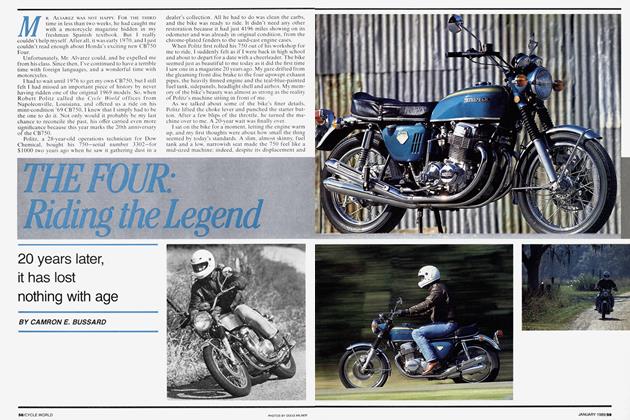

Besides, the importance of the Four wasn’t so much just in its performance, but in its style. The 750 combined performance with a new level of mechanical reliability, as well as rider comfort. For a generation raised on Twins, the smoothness of the Four had to be experienced to be believed. And the mechanical reliability was something very real; amidst an era in which English Twins were reaching a nadir in quality, the Honda Four was a motorcycle that could go 40, 50, even 60 thousand miles with only minor maintenance. The Four was as complete a package as motorcycling had ever seen. When Triumph’s Don Brown first saw it, and heard the price, he knew his company’s days were numbered.

This is not to say the first Honda 750s were perfect— they were not. While 67 horsepower isn’t much today, no roller chain of that era could handle it for long, and many an early 750 had its crankcases wasted by a thrown chain. Rear tires evaporated almost as quickly as chains stretched. The original design that combined four separate carburetors with four separate throttle cables almost guaranteed that carb synchronization would be a rare event, something to be enjoyed only for a short while after a tune-up. And the four individual mufflers were quick to rust. But in balance, these problems were no more than a few blemishes on a beautiful woman, and easy to ignore. They were also blemishes Honda was quick to correct in later models.

The biggest problem was producing enough of the Four; in the first year, the factory ran overtime to keep up with sales, and produced nearly 40,000 CB750s, most destined for the American market.

Almost overnight, the 750 Four became the motorcycle that could do anything. It was a touring bike; the aftermarket fairing business it would create would make Craig Vetter a rich man, and strike a path that would eventually lead to today’s Gold Wing. It was a performance bike; it launched names big and small in the hop-up business—Kerker, Action Fours, R.C. Engineering (and from there, Vance & Hines), to name just a few. It could be a racer, competitive enough to win the 1970 Daytona 200 for Dick Mann when tweaked by the factory somewhere near the bounds of legality, less competitive for most others in AMA Nationals. It was a blank canvas that sold in record numbers, and on which American motorcyclists drew as they wished.

In just a few short years after the 750’s arrival, the British, weakened by their internal problems, had suffered a complete rout, and conceded the large-displacement market largely to Honda. Harley-Davidson was driven farther from the market mainstream, leaving the company that had created the big, bad Sportster without a performance bike that could be taken seriously; it survived the 1970s by building products that were Harleys first, motorcycles second.

Eventually, even the 750 Four would fall victim to its own success, with the strongest competition coming from machines that were, if not copies, then clearly improved versions of the original. Kawasaki’s Z-l emphasized the desirability of the configuration, even as it took sales away from Honda, and Suzuki’s early GS models showed how refined a Four could be. Finally, in 1978, Honda replaced the CB750 with a bike sportier and more powerful than its predecessor; it was never to sell as well.

By then, the transverse inline-Four was such a common configuration for motorcycles that a wiseass pundit coined the abbreviation UJM (for Universal Japanese Motorcycle) to quickly place it; almost as quickly, Honda tried to abandon the inline-Four for V-Fours, a move that was less than a complete success.

That the CB750’s successors have never met the same acclaim is easy to understand now. From the vantage point of 20 years later, the CB750 Four was easily the most important motorcycle of its time, and, in many ways, the creator of the motorcycling world we now know. It started the revolution, and broke the trail. How could those that followed possibly burn as brightly in memory, or howl as sweetly? E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

JANUARY 1989 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

JANUARY 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Departments

DepartmentsLeanings

JANUARY 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

JANUARY 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupMotorcycles Behind the Camera

JANUARY 1989 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupRiding the Dart

JANUARY 1989 By Alan Cathcart