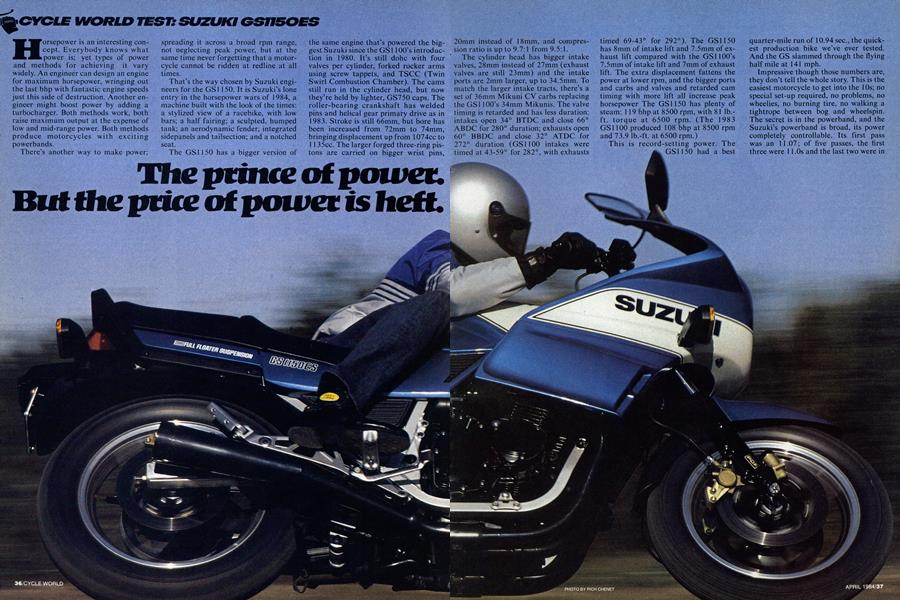

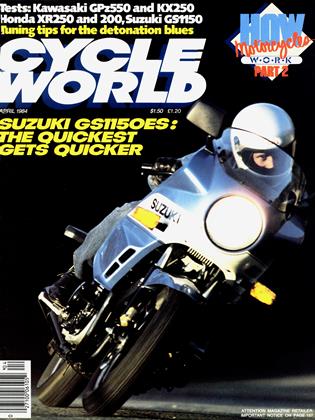

SUZUKI GS1150ES

CYCLE WORLD TEST:

The prince of power. But the price of power is heft.

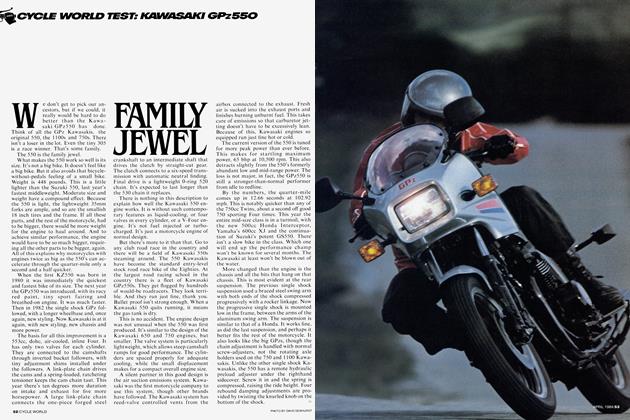

Horsepower is an interesting concept. Everybody knows what power is; yet types of power and methods for achieving it vary widely. An engineer can design an engine for maximum horsepower, wringing out the last bhp with fantastic engine speeds just this side of destruction. Another engineer might boost power by adding a turbocharger. Both methods work, both raise maximum output at the expense of low and mid-range power. Both methods produce motorcycles with exciting powerbands.

There’s another way to make power; spreading it across a broad rpm range, not neglecting peak power, but at the same time never forgetting that a motorcycle cannot be ridden at redline at all times.

That’s the way chosen by Suzuki engineers for the GSI 150. It is Suzuki’s lone entry in the horsepower wars of 1984, a machine built with the look of the times: a stylized view of a racebike, with low bars; a half fairing; a sculpted, humped tank; an aerodynamic fender; integrated sidepanels and tailsection; and a notched seat.

The GS1150 has a bigger version of

the same engine that’s powered the biggest Suzuki since the GS1100’s introduction in 1980. It’s still dohc with four valves per cylinder, forked rocker arms using screw tappets, and TSCC (Twin Swirl Combustion Chamber). The cams still run in the cylinder head, but now they’re held by lighter, GS750 caps. The roller-bearing crankshaft has welded pins and helical gear primary drive as in 1983. Stroke is still 66mm, but bore has been increased from 72mm to 74mm, bringing displacement up from 1074cc to 1135cc. The larger forged three-ring pistons are carried on bigger wrist pins, 20mm instead of 18mm, and compression ratio is up to 9.7:1 from 9.5:1.

The cylinder head has bigger intake valves, 28mm instead of 27mm (exhaust valves are still 23mm) and the intake ports are 2mm larger, up to 34.5mm. To match the larger intake tracts, there’s a set of 36mm Mikuni CV carbs replacing the GS1100’s 34mm Mikunis. The valve timing is retarded and has less duration: intakes open 34° BTDC and close 66° ABDC for 280° duration; exhausts open 60° BBDC and close 32° ATDC for 272° duration (GS1100 intakes were timed at 43-59° for 282°, with exhausts timed 69-43° for 292°). The GS1150 has 8mm of intake lift and 7.5mm of exhaust lift compared with the GS1100’s 7.5mm of intake lift and 7mm of exhaust lift. The extra displacement fattens the power at lower rpm, and the bigger ports and carbs and valves and retarded cam timing with more lift all increase peak horsepower The GS1150 has plenty of steam: 119 bhp at 8500 rpm, with 81 lb.ft. torque at 6500 rpm. (The 1983 GS1100 produced 108 bhp at 8500 rpm and 73.9 lb.-ft. at 6500 rpm.)

This is record-setting power. The GS1150 had a best quarter-mile run of 10.94 sec., the quickest production bike we’ve ever tested. And the GS slammed through the flying half mile at 141 mph.

Impressive though those numbers are, they don’t tell the whole story. This is the easiest motorcycle to get into the 10s; no special set-up required, no problems, no wheelies, no burning tire, no walking a tightrope between bog and wheelspin. The secret is in the powerband, and the Suzuki’s powerband is broad, its power completely controllable. Its first pass was an 11.07 ; of five passes, the first three were 11.0s and the last two were in the 10.90s.

The amazing thing is that the Suzuki did under the worst of conditions what other motorcycles have been able to do only under the best conditions. Orange County International Raceway is closed to dragstrip testing now, and Carlsbad Raceway (where we tested the Suzuki) lacks Orange County’s starting area traction and is plagued by timing light malfunctions that invariably delay testing until the dense, early-morning air has been warmed and thinned by the sun. There’s every reason to believe that the 1150 would be capable of 10.80 quarter miles if Orange County was still open.

The same powerband that makes the Suzuki a tractable rocket at the drags makes it especially well suited for street use. It feels normal to shift at 4000 rpm; running through the gears between 3000 and 4000 rpm at half throttle is deceptive, the engine seems relaxed and lazy, but the speedometer winds up quickly. Roll on three-quarters or full throttle and let the engine rev toward the 9000 rpm redline and the acceleration is explosive, the front end getting light in lower gears, the rear tire hazing over slick spots. Then the Suzuki is anything but deceptive; the pilot’s first thought is “This thing’s fast!” and that’s exactly right.

More power means more heat and more stress on parts, and the GS1150 is, equipped to handle both. There’s a new Nippondenso oil cooler and a larger sump, together holding 4.2 quarts of oil instead of the GS1100’s 3.4 quarts. The clutch is redesigned with a larger backing plate and gear assembly. The clutch gear has two more teeth and the crankshaft gear has one more tooth, slightly altering the primary drive ratio from 1.775 to 1.780:1. The cush springs built into the backing plate are larger and stronger and the 17 plates are thicker than the 20 plates used in the 1983 GS1100’s clutch. (All of which didn’t keep the 1150’s clutch from overheating and becoming grabby after those five quick passes at the drags. Then it showed all the characteristics of a clutch with burned and warped plates, and suddenly it was impossible to slip the clutch accurately to avoid wheelspin. Fortunately, that’s a dragstrip problem Suzuki riders are not likely to face during even the hardest street use.)

Both shafts in the five-speed transmission are made of stronger material, as are the second, fourth and fifth driven gears. The bearing behind the countershaft sprocket has larger balls to increase its capacity by 20 percent.

Bigger pistons and heavier, stronger parts often produce more vibration along with more power, and that’s certainly the case with the GS1150 engine. So the Suzuki has gained rubber front engine mounts built into the mount plates, not the crankcases (which are interchangeable with GS1100 cases). The rubber front mounts are right off the Suzukis raced in endurance and Formula One events, and are effective in reducing vibration. That isn’t to say that some vibration doesn’t reach the rider—it does. It’s most noticeable at 60 mph, felt through the handlebars, but the engine is smooth below 60 and smooths out again at about 65 mph.

There’s another annoyance at 60 mph, one that rubber mounts can’t cure. The GS1150 surges slightly at that speed on level ground, unable to hold a steady rpm even when the twist grip isn’t moved.

Speed up a little and the surge disappears; slow down and it also disappears. But right at 60, it’s there.

Ignition timing is still 32° at full advance, but there’s a new advance curve, controlled electronically without the weights-and-springs mechanical advance mechanism of the GS1100. Full advance is reached later (at 3500 rpm instead of at 2350 rpm) and there’s less advance below 1500 rpm (10° instead of 12°). The advance curve changes are designed to discourage detonation at low rpm, a common GS1100 problem, especially on hot days. In this case, the intention and the reality match. The GS1150 doesn’t have the GS1100’s knock and ping when the throttle is rolled on at 1500 or 2000 rpm.

Other changes make the GS1 150 engine more compact than the GS1100 engine. The ignition cover is thinner because it doesn’t have to fit around a bulky mechanical advance. The alternator cover doesn’t stick out as far because the GS1150 has the smaller (and less powerful) Katana alternator; the cover is beveled at the bottom to increase cornering clearance. The clutch cover has a new, flatter profile and fits closer to the crankcases. As before, the clutch and alternator covers are secured by bolts with 8mm hex heads; the ignition cover’s bolts have 7mm heads. Unfortunately, there isn't a 7mm wrench in the tool kit. (For the record, our test bike’s tool kit contained open end 10/12mm and 14/17mm combination wrenches, a stamped dual-purpose T-handle and 8mm open end wrench, a plastic screwdriver handle, a dual end (Phillips and straight blade) screwdriver bit, a larger Phillips head bit designed to be used with either the T-handle/8mm or the screwdriver handle, a 24mm socket wrench, a plug socket to be used with a screwdriver bit as a handle, and a set of pliers.)

A new cam cover is smaller, follows the form of the valve gear, and makes maintenance easier; it’s secured by 10 centralized bolts and is sealed by a onepiece, reuseable rubber gasket incorporating cam end seals (the 1983 GS1100’s cam cover used a paper gasket and four cam end seals held in place by 24 small bolts). There isn’t a tach drive built into the cam cover because the GS1 150 has an electronic tach.

The speedometer, though, is still driven by cable off the front wheel. Both tach and speedo fit into a console mounted in the fairing. There’s a small fuel gauge set into the console face above the speedometer, and an oil temperature gauge above the tach. Centered between the fuel and oil temp gauges is an LCD gear indicator. An odometer and a tripmeter are built into the speedometer face, and the console is framed on each side by indicator lights for turn signal use, low oil pressure, headlight or taillight/stoplight failure, high beam use, neutral selection or sidestand deployment. A red warning light beneath the console warns if battery fluid is low.

The plastic fairing mounts to the frame and has an inner shell. A lower section on each side is held in place by prongs fitting into rubber grommets on the fairing and on a tubular framework that bolts to the chassis. Scoops at the front of each lower direct air past the cylinder head. A giant, 8-inch quartz halogen headlight is built into the fairing. Turn signals on short, flexible stalks protrude from the fairing sides; the windscreen is flanked by rectangular, wideangle mirrors on stubby supports.

The fairing isn’t just for looks.

With the rider sitting upright, the fairing blocks wind that would normally hit at chest level, and the wind blast hits the rider’s helmet at eye level. Tucking in behind the remarkably distortion-free windscreen reveals a nice, calm pocket of still air, just like on a real road racer. The lower fairing sections reduce the wind reaching the rider’s legs, a blessing on cold nights. (But we’re not sure how well that will work out on hot summer days.)

The front fender is also plastic and flares ahead of the fork legs. The fender is held by an aluminum mount that doubles as a fork brace and as an air scoop aimed at the oil cooler and cylinder head.

Like the fairing lowers, the sidepanels attach with prongs fitting into rubber grommets. The gas tank holds 5.3 gallons and has an odd humped shape with ornamental vinyl pads. The gas cap looks like the aircraft filler caps Suzuki uses on its works endurance bikes: a small lever fits flush into the cap, and is flipped up and turned to remove the cap. But the Suzuki’s cap has a built-in lock and fits into a very narrow filler neck designed for use with a California-required evaporative emissions system, in which a canister of charcoal captures gasoline vapors venting from the tank. The cap and filler neck, which make it harder to get gasoline into the tank without spilling or splashing, are the only components of the system on the GS1150; there’s no canister in place, and, as a result, the 1984 1150s sold in California were all brought in before January 1 and declared as 1983 models.

The split-level seat is made in two pieces: the rear section bolts down and hides a sliding, plastic tray holding the tool kit and a small security chain with a magnetic-key padlock. (It’s doubtful that the chain would protect the GS from thieves. Most people would be reluctant to leave a bicycle protected by such an inconsequential device.) The front section of the seat pops off to reveal the (at last!) easy-to-service battery; the seat latch is operated by a key lock via cable. The lock itself also operates a helmet hook and is built into the left side of a padded grab rail running underneath, then behind and over the rear seat section.

There’s a wrap-around taillight beneath the grab bar. Below the taillight is a short plastic fender and a separate cover for the license plate light. The rear turn signals stick out from the sides of the fender.

The Suzuki’s frame is a combination of round and rectangular section steel tubing, painted silver. The backbone and the top of the rear section use round tubes. But the dual engine cradle/downtubes and the visible parts of the rear subframe use rectangular tubes. The swing arm is box-section aluminum with internal sliding-block axle adjusters and Suzuki’s Full-Floater progressive-linkage single rear shock system. Compared with the 1983 GS1100, the GS1150 has the same rear wheel travel at 4.5 inches. But due to the shock linkage, the GSI 1 50’s rear shock doesn’t have to move as far to deliver that wheel travel, 3.0 inches to the GS1100’s 3.3 inches of shock stroke. Rear shock rebound damping and preload are remotely adjustable by a set of knobs positioned just under the seat lock. The damping adjustment knob has four numbered positions; the preload adjuster is hydraulic with five numbered positions. Turning the knobs makes noticeable differences in ride height (preload) and rebound (damping). But although the GS1150 gave us no trouble, we’re leery of the hydraulic preload adjusting system because another Suzuki test bike (our long-term GR650) lost pressure and sagged to the minimum position. Repairs required exchanging the shock unit to Suzuki; that cost $260.

The forks have 37mm stanchion tubes, just like the GS1100’s forks, and the same 5.9 inches of travel. There are still adjustable spring preload cams at the top of tubes, hidden under rubber caps, and air pressure is still adjustable through a linked fitting. But besides the addition of the brace/fender support/air scoop mentioned earlier, the GS1150’s forks differ from the GS1100’s in the anti-dive system used. The GS1100’s system was activated by brake system pressure, and did more to reduce brake feel than to actually slow fork dive. The new system increases damping as the forks compress: damping rises according to fork travel. The system works on pressure. As the forks compress, damping oil pressure rises. There’s a sensor built into the damping control unit mounted on each fork leg; when pressure reaches a certain point, a spring-loaded valve closes, restricting oil flow and thus increasing damping. A dial on top of each control unit has four positions, and which position the dial is set at determines how soon (in terms of fork travel) the damping-increasing valve closes.

With the new forks come new brakes, two 10.75-inch surface-slotted stainless steel discs up front, one in the rear, all with dual-piston calipers. Couplers between the discs and the disc carriers allow the discs to float slightly side-to-side. The floating mounts and surface slots are, again, racebike tricks, the first to discourage disc-warping and the second to avoid pad glazing.

What didn’t come off any racebike we’ve seen is a finned aluminum line junction mounted on the lower triple clamp, joining the front caliper lines with the single line leading to the master cylinder.

With the new brakes come new wheels, much wider than the wheels seen on previous Suzukis. The front is 2.50 x

16 inches and carries a 110/90V-16 Bridgestone G515 tire. The rear wheel is 3.00 x 17 inches, fitted with a 130/90V-

17 Bridgestone G516 tire.

The handlebars are forged aluminum with short I-beam risers that fit around the stanchion tubes and bolt to the upper triple clamp. The usual controls are mounted in pods on the bars, including engine kill switch, starter button, horn button, a combination turn signal/headlight beam switch and a choke lever. The brake and clutch levers have dogleg bends, and there’s a clutch interlock switch: the starter won’t work unless the clutch lever is pulled in.

The footpegs — forged aluminum bases with rubber inserts—are rearset and rubber mounted to a light aluminum casting bolted to the frame rear section. The peg carriers also support the passenger pegs and the mufflers. A linkage with heim joints and a threaded rod connects the shift shaft with the shift lever; the rear brake pedal pivots underneath and behind the right peg and is linked to the remote-reservoir rear master cylinder through a short lever and a rod.

This is a long motorcycle. Wheelbase is 61 inches compared with the GS1100’s 59.4 inches, and most of the increase comes from extending the swing arm to make room for the single rear shock. Rake is still 28°, trail 4.6 inches.

It’s also a big motorcycle, weighing 557 pounds on our certified scales (the 1983 GSI 100S weighed 552 pounds).

And it feels long and big and topheavy when the rider climbs on and grabs the short handlebars. The GS starts easily enough when cold, providing the choke is used, but the rider must hold the spring-loaded choke lever in position while starting and for several miles after getting underway. It’s awkward and inconvenient.

There are other niggling distractions. The footpegs are too high for long-legged riders, and their legs cramp on long rides. The handlebars are not as extreme as the bars on the Katana, but they still cause wrists and hands to ache in slow traffic. The shift linkage is routed over the shift lever, not under, and the rear joint is level with the top of the footpeg; it’s easy for the rider to hit the heim joint with the sole of his boot, keeping the lever from returning after a downshift or causing the transmission to jump out of gear. The rider can’t see the road directly behind the bike because the mirrors show his jacket sleeves instead.

The overwhelming impressions, though, concern power and size . . . and brakes. Which of those seems most important at any given time depends upon the circumstances.

Blasting past traffic with barely a yawn from the engine brings nothing but admiration for the power, and on most roads at mostly-legal speeds, the size of the GS1150 never enters into the rider’s mind.

But get off the highway and into some curves and SIZE rears up and stands at attention. Yes, the Suzuki has a 16-inch front wheel, and yes, it turns easier than the GS1 100. But much of the advantage gained by the 16-inch front wheel is lost to the 61-inch wheelbase and 557 pounds. Don’t misunderstand: the Suzuki is stable and steady, with good cornering clearance (the pipes and stands are very well tucked in, and only the pegs drag as the tires reach the edge of their tread). But this isn’t a motorcycle that’s snapped easily into a fast sweeping turn or rifled up a set of Sturns. The tighter the road, the faster the pace, then the more effort it takes to hustle the Suzuki along.

Brakes. In theory, going by looks and specifications, the GS1150’s brakes should be superior to the GS1100’s brakes. But in practice they aren’t. Consider the stopping dtstances: 118 feet from 60 mph and 32 feet from 30 mph for the 1983 GSI 100S; 131 feet from 60 mph and 38 feet from 30 mph for the GS 1150. All three discs turned blue during the braking tests, but the biggest problem is control. The 1150’s front brakes require a stronger pull than the GS 1 100’s brakes, almost as if Suzuki engineers, tired of hearing that the GS1100’s brakes lacked feel, decided that less lever travel and a firmer pull produces good feedback. That isn’t the case, and this Suzuki is proof.

It’s more than simply feel or lack of it that plagues the rear brake. It is too sensitive and locks instantly with far too little pedal travel. Suddenly the rider who’s trying to make a very quick stop is distracted from his primary task, stopping, and has to deal with a locked, sliding rear wheel which immediately and invariably steps out to one side. That’s not what a rider wants when trying to avoid an errant Falcon wagon from Shady Grove Rest Home.

This isn’t a matter of easy adjustment: the brake pedal is level with the top of the footpeg, and the splines on its pivot shaft are too coarse to allow any adjustment between too high and too low. There is a threaded rod linking the pedal pivot and the rear master cylinder, and turning a fitting on the end of the rod can adjust pedal height. But there’s no way to adjust pedal travel before lockup, and that’s the critical error.

In any case, the performance of the Suzuki GS1150’s brakes is no match for the strong, linear power with excellent feedback delivered by the brakes on several Kawasakis and Hondas.

Which brings us to the crux of the matter. In a straight line, the Suzuki’s brilliant engine with superb power and torque at every rpm makes it easy to ride and difficult to beat. But anywhere else, the GS1150’s bulk and size and shortcomings assert themselves.

The GS1150 is a machine built to compete with the GPzl 100, the now-discontinued CB1100F, the Honda V65, and, yes, the GS1100. The big Suzuki is a match for any of those bikes. But the new wave, the trend in high-performance super sports motorcycles is toward llOOcc power packed into scaled-down, lightweight, short-wheelbase chassis; that trend is seen in bikes like the GPz900R Ninja, the FJ1100 Yamaha, the 1000 Interceptor.

The competition and the rules have changed faster than the Suzuki; because it has not changed enough, the GS1150 is in danger of being left behind. 13

SUZUKI GS1150ES

$4785

View Full Issue

View Full Issue