KAWASAKI KX250

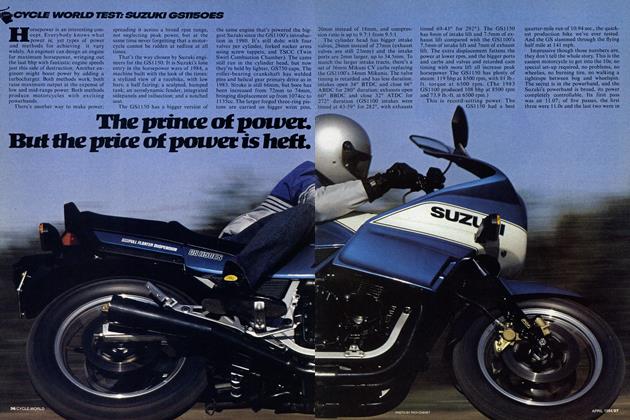

CYCLE WORLD TEST:

COOL, GREEN AND COMPETITIVE

Kawasaki isn’t famous for radical change. Improvement and development is more like it, as seen in Uni-Trak rear suspension and the last and fastest of the factory turbos.

And as seen in the 1984 KX250. Just as with the turbos, Kawasaki was the fourth of the Big Four to adapt water-cooling to its 250 motocrosser. Not needed, they said when the others did it, and it wasn’t until last year that the utility—or perhaps the need to look modern—persuaded Team Green to go the water jacket route.

More important, when the KX got water-codling the designers used the opportunity to make s¿Vne, other improvements as well.

The 1984 engine is the same basic design as used in 1982 on the last of the air-cooled 250s. With a bore and stroke of 70 x 64.9mm, it’s moderately oversquare. The induction system uses a reed valve, direct to the cylinder with boost ports from the reed cavity to the transfers, bypassing the crankcase. The CD ignition is on the outer edge of the flywheel, so there’s lots of flywheel effect for the weight. Overall, the watercooled engine is stronger, thanks to wider mating surfaces for the cases, stiffener ribs for the main bearing on the ignition side, and more metal around the cylinder studs the cylinder’s mounting base. The clutch gets friction plates, with a cross-hatch pattern on surfaces for better oil flow. The cylinder bore Kawasaki’s Electro-fusion coating, which reduces wear although it can’t be re-bored.

The other engine changes, from the air-cooled 1982 and the water-cooled 1983, which we didn’t manage to test, sorry, stem from the adaptation radiators.

Water-cooling does two things. First, because lets an engine run cooler, longer, the water-pumper 1 can be run harder, longer. Second, because heat "be controlled as well as extracted, the engine nave more peak power.

Which the 1984 KX250 has. The compression ratio was raised, the exhaust and boost ports were modified and the ignition advance curve and exhaust system revised to work with the above modifications. Claimed power is now 45 bhp 8500 rpm; a gain of a few bhp from 1983, and more than that compared with 1982.

The carburetor is a 38mm Mikuni, of a design unique to Kawasaki. It’s called the R-Slide, cause while the conventional Mikuni slide bottom curved, this one has a flat bottom with a rounded groove running down the center, back to front, above the needle jet. In theory, the smaller, shaped passage means better mixture and better response at partial throttle openings.

Last year’s KX frame was revised for the engine and the 1983 version of the single shock rear suspension. The ’83 didn’t look as new as it was, mostly because the seat> didn’t have the tapering, padded front seen on works bikes and the rival production bikes.

This year, you guessed, the KX gets the tapered (safety) seat, and both the tank and radiators are mounted lower on the frame. The rear shock linkage is revised, an annual thing, and the swing arm has been lengthened a fraction of an inch in keeping with the changed shock leverage system.

As part of current thinking, the steering head angle has been steepened, from 30° on the air-cooled KX to 28.5°on the new bike. Making the steering head angle steeper moves the front wheel closer to the frame, so the KX’s wheelbase is an inch or so shorter despite the slightly longer swing arm.

Shortening the front of the wheelbase while lengthening the back, so to speak, shifts the weight of the engine, radiators and fuel tank to the front. The ’84 KX250 has a weight distribution of 49.6 percent front, 51.1 percent rear, compared with the ’82’s distribution of 47.8/52.2.

All this makes sense. The current vogue for motocross posture is sitting well forward, on the tank, crouched low'. Corners are taken with rider weight as close to the front wheel as possible, which is why the short tanks and padded seats. It’s done to put more weight on the front wheel, for better bite. Naturally, the forward shift of the engine, etc., helps this. And there’s so much power in the 250s now that the front gets light at full throttle, so the change in distribution helps there, too.

The wheelbase and steering angle revisions are to make the bike turn quicker, at the expense in the book anyway of stability on the straight. Tight tracks in the stadium style are popular, so the swap should be a gain.

Included in the list of neat stuff are new hubs with straight-pull spokes, and a bracket above the front fender to brace it against loads of mud. That bracket, the kick start lever, swing arm, brake pedal, shift lever, shock body, rims and rebuildable silencer are all aluminum.

Oh. Test weight of the ’84 is 229 pounds. We’re told the ’83 weighed two pounds less, while we weighed the ’82 at 228 pounds. The new machine carries 0.3 gallons less fuel, call it two pounds, so the added power didn’t bring an equivalent penalty in beef.

The suspension is modern and adjustable. The KYB forks have eight-position compression damping, adjusted by a screw on the bottom of the slider. Changing oil volume and/or oil weight, or adding air pressure gives a broad range of choices. Changing the compression damping requires standing on one’s head, same as on the other brands, but once they do it, most riders never need to change it again.

The KYB shock features four compression and four rebound settings. The rebound control knob is at the top of the shock and requires removal of a plastic side plate to reach. And the knob is buried way in there. Kawasaki's excellent owner’s manual suggest is using a flat-blade screwdriver to turn the wheel. The knob is clearly marked from one, the softest, to four, the stififest. Adjusting compression damping is easier; the control knob is on the end of the remote reservoir. Adjusting spring preload, never simple on past models, is easier this year. The adjuster wheels can be reached with a long punch. Kawasaki reps also recommended a different way; put the bike on a stand and remove one of the bolts from the aluminum link that runs between the swing arm and rocker. That lets the rear wheel drop enough to reach the adjuster. Removing the splash guard between the shock and rear wheel makes enough room to use a spanner wrench.

The Uni-Track progression curve is altered once again, with a different rocker length and the longer swing arm. The change results in a overall softer, flatter curve and almost a half an inch more rear wheel travel. Lubricating the rear suspension is easier thanks to grease fittings on the end of the dogbone link but the swing arm bushings and rocker still require disassembly.

Brakes are everything you could ask for. A hydraulic disc at the front means you’ll easily get the bike slowed at the end of that killer straight. A drum rear brake is enhanced by an aluminum static arm that eliminates suspension lock-up when the brake is used hard on whooped ground.

The shift and brake pedals have folding tips. The hand levers, throttle, grips and bars are good and fit most riders. Footpegs have open bottoms that don’t hold mud but do get bent easily. The pipe extends below the frame in front but tucks in nicely everywhere else. The aluminum silencer is a gem; the extruded housing has a top ridge that becomes a double mounting bracket after it’s trimmed. It’s a strong, good looking way to do it. Additionally, the unit is easily repacked after removing two screws.

The exhaust pipe has double O-rings to seal leakage where the headpipe enters the cylinder. The radiator-to-engine water hoses are few, thanks to sensible routing; the water leaves the engine, enters the bottom of one radiator, exits at the top, enters the top of the other radiator, then returns to the engine. Y’s and double hoses are eliminated.

The countershaft sprocket is retained with a simple clip, no nut to fiddle with. The transmission oil level is quickly checked with a glance, thanks to the sight window in the clutch-side cover. There’s a coolant drain plug on the bottom of the water pump cover.

Starting the KX250 is straightforward; the fuel petcock is off in its middle position, on when turned to either side. The choke lever is easily reached and stays put when lifted to the on position. The kick lever is on the right side of the bike and has a good raised-ridge surface that keeps boot soles from slipping. The engine spins several times with each prod although it does take a hefty kick. Several kicks are usually required to get the engine running.

The clutch pulls smoothly and easily, and the transmission drops quietly into low or second. The clutch releases in a jerking manner if released slowly, but doesn’t if dropped suddenly, motocrossstart style. Shifting is smooth and positive if the clutch is used, a little notchy if it isn’t used. Gear ratios are perfect for the engine’s power and the bike moves swiftly away from the starting gate.

The KX’s power is competitive. Right, 45 bhp from a 250 sounds like world champion equipment, but all the production bikes, well, most of them, crank out this much muscle. Peak power is there, but our bike was soft on the low end with a flat spot right off idle. We suspect that when more people have more time with the R-Slide carb, and when the parts are available, there will be ways to improve and maybe even cure it. (Check the Honda XR test in this issue for the sort of improvement the local guys can come up with once the factory lets them fiddle.)

Even so, no big. Racing means not bothering with the first eighth turn of the throttle anyway and if you do get caught with revs down, fanning the clutch in 125 style will get the engine back into the useful band.

Steering and handling, competitive again. The steering is usefully quick; it will follow instructions while not getting away from the rider’s intentions. And the rider can slide forward.

Speaking of that, the rider can also slide backward, but won’t do it often. The rear fender is one of the older parts on the bike, with panels for numbers on the sides and stiffening ribs along the top.

When the back of the bike gets kicked up, which it will, the fender whacks the rider in the butt and those ribs don’t help at all.

Front suspension is just about faultless. Easily tuned, adequate travel.

The rear shock needed minor attention. When we first rode the KX it looked as if the back of the bike was moving around a lot. Not back and forth, not kicking or hopping, just moving up and down while the wheel stayed on the ground. We clicked the rear rebound damping up one notch and the excess motion was gone. After that, no problems with landings or jumps or keeping between the berms.

The rear brake was fine, the front is plenty strong. Except that it grabbed until it had been heated, then cooled. And by the end of the next riding session, the lever was coming back to the grip. We adjusted the lever back out, went three more laps and the lever was hitting the grip again. A serious session with the brake bleeder and it’s worked well since.

The KX is narrow in the middle, which with the low tank and firm seat lets the rider jockey for position without interference.

Relativity, that’s the problem here. The KX250 doesn’t lack anything, not power or wheel travel or brakes. But we didn’t use it to dust off highly-rated open class bikes, and we didn’t sweep the pro class at local tracks.

Kawasaki has a good support and continency program, which helps the club racer, and what the factory offers with the KX250 is a machine the club racer can use.

Competitive. El

KAWASAKI KX250

View Full Issue

View Full Issue