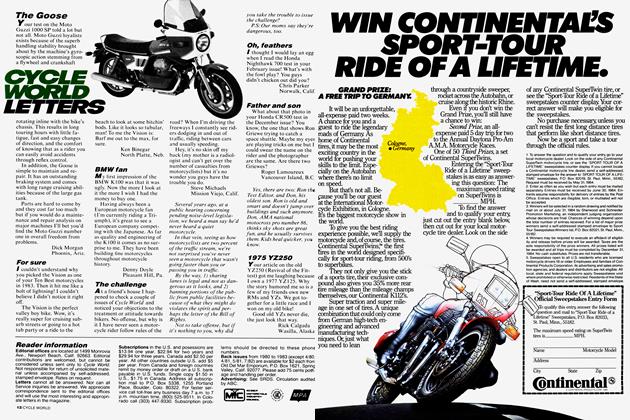

ONE MAN'S INDIAN

You may not get better as you get older, but you do get to make some dreams come true.

Clifford Bobb

“What kind of bike is that?” “Indian.” “What?” “It’s a 1948 Indian.”

The young man on the water-cooled, shaft-driven, multi-cylinder Japanese import had pulled along-side me at a traffic light and was giving my venerable machine a quick once-over: “Neat!”

I hoped he meant it. Thanks to a year and a half of spare time work, an adolescent fantasy had come true. As a teenager I spent many hours at the local Indian agency, lusting after the big, streamlined machines built in the immediate post-World War II years. But they cost one thousand-plus dollars a copy and I had about as much chance of buying one as I had of putting a down payment on the Moon. So, 34 years later, a grandfather and a bit better off financially than I was in 1948,1 decided to make at least one of my many unfulfilled dreams come true.

Having reached this decision, the next step was to inform my wife. I decided that the direct approach was best: “Honey, I’m going to restore an old motorcycle.” She had no difficulty in restraining her enthusiasm. Mumbled something about male menopause and mid-life crisis, I think. “Why a motorcycle, why not an old car? You like old cars, don’t you?” she asked somewhat hopefully.

Why, indeed? I suppose I could have been happy with a Lincoln Continental or a Packard but if you’re an avid cyclist, the answer is simple: You like motorcycles. Besides, there are factors like space and cost to consider. For instance, restoring the interior of even so basic and unpretentious a car as a Model A Ford costs more than $900. I had the Indian saddle reupholstered in genuine leather—The Saddle! Genuine leather!— for just $125. And a complete frame-off disassembly of a car takes five times as much space as a motorcycle. I know how packed my garage is, and I bet I know how yours is, too.

So, as my wife’s fingers scampered through the yellow pages, divorce attorney or marriage counselor I couldn’t tell which, I searched through back issues of Hemmings Motor News in search of my dream machine. In looking through the “Cycles and Parts” section, I was surprised to see ads for clubs, publications and parts suppliers devoted exclusively to antique motorcycles. I sent for a couple and concluded very quickly that in restorable condition, the machine I wanted would be in the $1500 to $2000 range.

After many phone calls and letters, I finally located what I wanted, or at least what I would settle for, within driving distance of my home. It ran, barely. Most of the parts were there, although not all of them were on the cycle. The front fender was missing, which did not upset me greatly since I knew that the attrition rate was high on these full skirted fenders. It did have one redeeming feature: The serial numbers on engine and frame were the same. The engine had never been replaced. This adds greatly to its value as an antique as well as providing personal satisfaction in having the equipment as original as possible; something to remember when searching for a vintage bike.

I tried to be objective as I continued my examination, but I couldn’t help imagining how it must have looked as the proud first owner rode it home from the showroom in 1948. What it must have been through since then, what stories it could tell. Well, I’d soon have it looking like new again. I had already begun thinking of it as my own, and of course, this is entirely the wrong attitude. One should be as objective as possible; details missed at the beginning will be paid for later.

At any rate, we agreed on a price. After the paper work was taken care of, we loaded the Indian onto my pickup, tied it securely, and I drove home wondering the whole way if perhaps my wife was right. Neighbors helped me drag the beast into my garage where it dripped black, gooey oil onto my new concrete floor and gave off fumes which would be the envy of your average polecat.

The very next evening I began to disassemble the bike, cleaning small parts as best I could with gasoline and Gunk. Soon the catalogs I had sent for arrived. Among the first things I ordered from one of them were a Rider’s Manual and an Overhaul and Repair Manual.

At first I made sketches of various sub-assemblies as I took them apart, but after receiving the manuals I discovered that over the years repairs on my bike had been made with only one thought in mind: Keep it running. As a result many items were either missing, assembled backwards, or had been replaced with (Forgive them, Lord) Flarley parts. From then on I relied solely on the manuals when it came time to reassemble carburetor, brakes, and other critical parts.

After I wore out my second wire brush, I began to wonder if there wasn’t a better way. There is. Most tool rental outfits carry sandblasting equipment; Not the gasoline-powered monsters used to clean brick and stone buildings, but small, electric powered models suitable for removing rust and paint, especially in hard to reach places or from intricate castings.

Although parts may look clean after scrubbing with solvents, a thin patina of oil and dirt has almost always penetrated a few thousands of an inch into cast or pitted metal. The removal of this small amount of material will not effect the appearance of the part and provides an even, uniform “tooth” for surfaces that are to be painted. Although sand will work, it can be extremely abrasive. A smoother surface can be had by using glass beads. These fine particles will remove corrosion and paint, but will not easily disturb solid, un-corroded surfaces.

I decided on the color that the bike would be painted almost from the moment I embarked on the project. It was to be modeled after a particular machine which I remembered seeing and admiring as a young man. Models from the Thirties and Twenties usually had frame and forks painted the same color as the sheet metal. But, in the 1940s the color you chose would only appear on the fenders, tanks, and chain guard; Everything else was either painted gloss black or was plated. Since gloss black is gloss black no matter where it comes from, I painted these parts myself with Krylon spray cans.

This brings up an important point. Repair manuals have been reproduced for many antiques. However, the biggest problem in restoration is not mechanical, but cosmetic. Had I realized this sooner, I could have saved myself a lot of time and effort. For example: When I bought the bike the kick starter was black. I assumed it was supposed to be. I carefully glass beaded it, primed and painted it, only to discover later that it was originally cadmium plated. Off came my new paint job, and off went the starter to the plater.

The moral is: Find a club which most closely satisfies your particular needs (the AMA might be able to help). Join it as soon as possible, talk to other members about your bike, find out when and where the meets are held. Go to as many as possible, not only those devoted solely to motorcycles, but the automotive ones as well. Buy advertising posters and brochures and color charts pertaining to your machine. Auto flea markets such as the ones held in Carlisle, Pennsylvania will often have dealers in literature and advertising material for motorcycles as well as cars. When going to the antique cycle meets, take along a good camera with a close-up lens. If you spot your machine in restored condition, take lots of close-up pictures, of as many details as possible. They will come in handy not only from the painting and plating aspects, but also when it comes time to route cables and wires and attach parts and accessories.

Among members of the Springfield Indian Motorcycle Club, which was the one I finally joined, was a former Indian dealer who supplements the income from his Honda dealership and supports his hobby by rebuilding engines and otherwise helping in the restoration of the motorcycles he used to sell. Since my small home workshop is not equipped to rebuild engines, I contented myself with disassembling and cleaning what I could, then turned that part of the project over to him.

With the engine in capable hands, and the frame and other smaller parts cleaned and painted, I turned my attention to the sheet metal. I had located a front fender at one of the cycle meets. It looked as though it had been under water since 1950, and had been drilled for the mounting of accessories which were no longer there, but enough of it was left so that an auto body shop could repair it. My ex-Indian dealer friend supplied me with templates made from a restored 1948 Chief and marked those holes in my fender which had to be welded shut. The rear fender, too, had holes drilled in it, for Lord knows what purpose, and these also had to be filled in. The gas tanks, although dented, were not in terribly bad condition. I figured a competent body shop could easily bring them back into shape.

One gas tank did leak slightly, however, and I decided to solder it myself. After washing it thoroughly to remove gas fumes, I placed it on the kerosene heater with which I was heating my garage, in order to dry it out quickly; I promptly forgot all about it. I ignored the cracking and pinging noises emanating from that end of the garage, thinking it was the heater warming up. By the time I realized what was really happening, it was too late. I pulled the tank off of the heater (I did remember to insulate my hand with a shop rag) and watched horrified as a rivulet of solder ran out of one end.

Well. Soldering a small leak is one thing, soldering the entire tank was something else. Besides, the tank I had just undone was divided by a bulkhead; The forward half was the oil tank, the rear half the auxiliary gas tank. A leak between them could result in gas from the auxiliary tank seeping into the front half of the tank and changing the oil into

Walneck’s Vintage Monthly Motorcycle Sales Publication 8280 Janes Ave. Antique Cycles Suite 17-A 1700 and parts Woodridge, III 60517 $14.00/year Bob’s Indian Parts, complete R.D. #3 or partial Etters, PA. 17319 restoration Indian Motorcycle Supply P.O. Box 1152 Aurora, III 60507 Indian Parts Springfield Indian Motorcycle Club of America 1352 Simpson Ferry Rd. New Cumberland, PA. 17070 $7.50/year Antique Motorcycle Club of America 3431 West 10TH St. Wichita, Kansas 67203 $15.00/year

SAE 5! This seemed to be another one of those jobs that are best left to experts. When I dropped off the tanks, along with

the rest of the body work, I didn't mention why one of the tanks was in such bad shape. After all, the bike is 35 years old. A lot can happen in 35 years.

The sheet metal parts went on with few real problems, and finally the day came when the only things left to do were install the battery and fill the tanks. This done, I tried to think of something else that needed doing. There wasn't anything. The Indian stood before me looking pretty much the way it must have looked 35 years ago.

“Aren't you going to start it?" My wife, who up to now had done her best to ignore the clutter in her garage, was now concerned that it might not run.

My right knee began to throb with the painful memory of the time the kick starter on my old Harley decided to kick back 30 odd years ago. My imagination took over: If I did manage to get it started without injuring myself, I would probably hear strange noises coming from parts I had assembled myself with almost no previous experience in motorcycle repair. I had never even ridden an Indian before; Indians had a left hand throttle, suppose I became confused and tried to slow down by twisting the right hand grip?

After a few' days of this self-inflicted torment, I could put it off no longer. Following instructions in the Rider's Manual, I kicked it over once with the choke closed and the switch off in order to prime it. On the third try with the sw itch on it roared to life. Well, it didn't exactly roar, it kind of sputtered and coughed, but with a bit of jiggling of spark advance, throttle, and choke it did begin to sound like a nineteen-forties motorcycle.

“When are you going to take it out on the road?" My wife shouted.

“Maybe tomorrow."

“Tomorrow" came a week later. The weather was clear, and I was tired of being intimidated by a brute on which I had spent over a year restoring to its former youth and beauty. So, I planned a short trip and apprised my wife of the route I would be taking: “Now, if I’m not back in half an hour or so, take the car and just follow this route." It must have sounded to her as though I was going to Fort Apache to warn the cavalry about an Indian uprising.

Finally, I started the bike, donned glasses and helmet, and after allowing it to warm up for a few minutes, disengaged the clutch and pushed the lever forward into low gear. The clutch on American bikes of this period consisted of two pedals, solidly connected to each other and pivoted in the center. Your heel rested on the rear pedal, your toes on the front, and it was operated by rocking your foot back and forth. Although awkward and unsafe compared to today’s hand clutch, it has been mistakenly referred to as a “suicide clutch." The suicide clutch, which was standard on four cylinder models, was a single pedal, spring loaded as on manual shift cars. It doesn't take a great deal of deductive reasoning to understand why such an arrangement on a two-wheeled vehicle was referred to as “suicide."

I slowly, very slowly engaged the clutch and began to move forward down my driveway and onto the two lane road in front of my house. Fortunately, I live in a rural area so I wouldn’t have to worry about heavy traffic.

I stopped once or twice before goingvery far, to be sure the brakes worked and to become accustomed to the feel of the clutch and throttle. Gradually my confidence increased and I shifted into second. Well, not quite; I missed second and hit neutral. But, before long I was cruising along in third and leaning from side to side to get the feel of the machine beneath me, as well as to check for any looseness in the suspension.

Since everything seemed to be working better than I had any right to expect,

I allowed my thoughts to drift back to the late Forties. I imagined myself pulling into Al’s gas station to show' off my new Indian to the gang that used to hang out there. The old arguments, usually friendly, between Harley and Indian riders would break out, with comments from the occasional Norton, Ariel, and Triumph owner.

Still daydreaming but alert enough to see the red light up ahead, I brought the Indian to a smooth, almost graceful stop. While waiting for the light to change, a motorcycle pulled alongside.

“What kind of bike is that?"

“Indian."

“What?"

Welcome back to the present. ®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue