KAWASAKI GPz550

CYCLE WORLD TEST:

FAMILY JEWEL

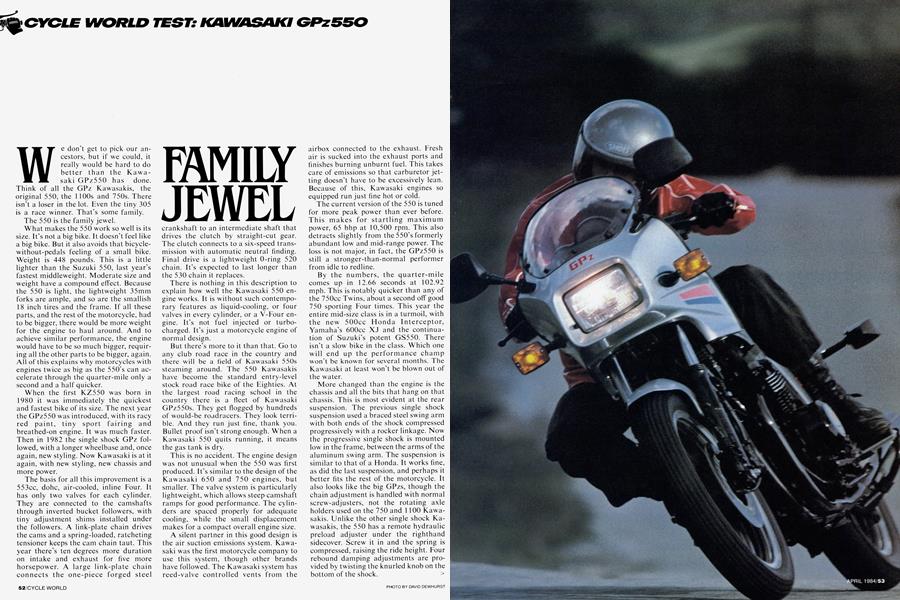

We don’t get to pick our ancestors, but if we could, it really would be hard to do better than the Kawasaki GPz550 has done. Think of all the GPz Kawasakis, the original 550, the 1100s and 750s. There isn’t a loser in the lot. Even the tiny 305 is a race winner. That’s some family.

The 550 is the family jewel. What makes the 550 work so well is its size. It’s not a big bike. It doesn’t feel like a big bike. But it also avoids that bicyclewithout-pedals feeling of a small bike. Weight is 448 pounds. This is a little lighter than the Suzuki 550, last year’s fastest middleweight. Moderate size and weight have a compound effect. Because the 550 is light, the lightweight 35mm forks are ample, and so are the smallish 18 inch tires and the frame. If all these parts, and the rest of the motorcycle, had to be bigger, there would be more weight for the engine to haul around. And to achieve similar performance, the engine would have to be so much bigger, requiring all the other parts to be bigger, again. All of this explains why motorcycles with engines twice as big as the 550’s can accelerate through the quarter-mile only a second and a half quicker.

When the first KZ550 was born in 1980 it was immediately the quickest and fastest bike of its size. The next year the GPz550 was introduced, with its racy red paint, tiny sport fairing and breathed-on engine. It was much faster. Then in 1982 the single shock GPz followed, with a longer wheelbase and, once again, new styling. Now Kawasaki is at it again, with new styling, new chassis and more power.

The basis for all this improvement is a 553cc, dohc, air-cooled, inline Four. It has only two valves for each cylinder. They are connected to the camshafts through inverted bucket followers, with tiny adjustment shims installed under the followers. A link-plate chain drives the cams and a spring-loaded, ratcheting tensioner keeps the cam chain taut. This year there’s ten degrees more duration on intake and exhaust for five more horsepower. A large link-plate chain connects the one-piece forged steel crankshaft to an intermediate shaft that drives the clutch by straight-cut gear. The clutch connects to a six-speed transmission with automatic neutral finding. Final drive is a lightweight 0-ring 520 chain. It's expected to last longer than the 530 chain it replaces.

There is nothing in this description to explain how well the Kawasaki 550 engine works. It is without such contemporary features as liquid-cooling, or four valves in every cylinder, or a V-Four engine. It's not fuel injected or turbocharged. It’s just a motorcycle engine of normal design.

But there’s more to it than that. Go to any club road race in the country and there will be a field of Kawasaki 550s steaming around. The 550 Kawasakis have become the standard entry-level stock road race bike of the Eighties. At the largest road racing school in the country there is a fleet of Kawasaki GPz.550s. They get flogged by hundreds of would-be roadracers. They look terrible. And they run just fine, thank you. Bullet proof isn't strong enough. When a Kawasaki 550 quits running, it means the gas tank is dry.

This is no accident. The engine design was not unusual when the 550 was first produced. It’s similar to the design of the Kawasaki 650 and 750 engines, but smaller. The valve system is particularly lightweight, which allows steep camshaft ramps for good performance. The cylinders are spaced properly for adequate cooling, while the small displacement makes for a compact overall engine size.

A silent partner in this good design is the air suction emissions system. Kawasaki was the first motorcycle company to use this system, though other brands have followed. The Kawasaki system has reed-valve controlled vents from the airbox connected to the exhaust. Fresh air is sucked into the exhaust ports and finishes burning unburnt fuel. This takes care of emissions so that carburetor jetting doesn’t have to be excessively lean. Because of this, Kawasaki engines so equipped run just fine hot or cold.

The current version of the 550 is tuned for more peak power than ever before. This makes for startling maximum power, 65 bhp at 10,500 rpm. This also detracts slightly from the 550's formerly abundant low and mid-range power. The loss is not major, in fact, the GPz550 is still a stronger-than-normal performer from idle to redline.

By the numbers, the quarter-mile comes up in 12.66 seconds at 102.92 mph. This is notably quicker than any of the 750cc Twins, about a second off good 750 sporting Four times. This year the entire mid-size class is in a turmoil, with the new 500cc Honda Interceptor, Yamaha’s 600cc XJ and the continuation of Suzuki’s potent GS550. Thereisn’t a slow bike in the class. Which one will end up the performance champ won’t be known for several months. The Kawasaki at least won't be blown out of the water.

More changed than the engine is the chassis and all the bits that hang on that chassis. This is most evident at the rear suspension. The previous single shock suspension used a braced steel swing arm with both ends of the shock compressed progressively with a rocker linkage. Now the progressive single shock is mounted low in the frame, between the arms of the aluminum swing arm. The suspension is similar to that of a Honda. It works fine, as did the last suspension, and perhaps it better fits the rest of the motorcycle. It also looks like the big GPzs, though the chain adjustment is handled with normal screw-adjusters, not the rotating axle holders used on the 750 and 1 100 Kawasakis. Unlike the other single shock Kawasakis, the 550 has a remote hydraulic preload adjuster under the righthand sidecover. Screw it in and the spring is compressed, raising the ride height. Four rebound damping adjustments are provided by twisting the knurled knob on the bottom of the shock.

Front suspension adjustments include air pressure and the anti-dive compression damping control. One air fitting on the lefthand fork leg fills both legs through the crossover tube. The anti-dive adjustments on the bottoms of the fork legs are now simple screw-in valves. There are no click stops. The smaller front tire and new frame come with steeper 26-degree steering head angle and 3.74 inches of trail. There’s also almost half an inch more front wheel travel.

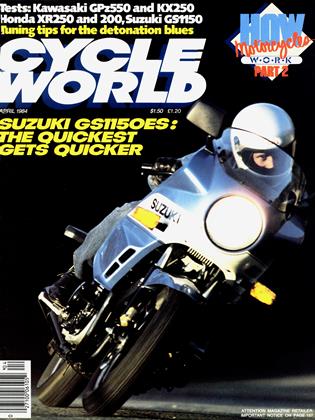

Suspension changes won’t be the most noticeable feature of the new GPz550. The color and styling are more exciting. As the photos show, GPzs are no longer always red. This is a metal-flake silver, a more metallic-looking silver than most, and it comes with as bright a red and blue trim as you’ve ever seen. You can still buy a red one, too.

Then there’s the fairing, styled just like the big GPz fairings. It mounts to the frame, tucks in close to the gas tank and has a small but useful windshield. Touring isn’t what Kawasaki had in mind with this fairing, though it’s handy to have on the open road. This is a racer replica, small and sleek and sporting. It keeps the wind blast off the rider’s chest, and puts it right at head level. Tuck in tightly behind the fairing and you have enough coverage to make 100 mph speeds easy, if not comfortable. Inside the plastic fairing is a molded panel that makes everything look finished. Instrumentation is the nowstandard GPz assembly of liquid crystals, blinking lights and two sizes of round gauge. This system is confusing on the big GPzs and it’s no better on the small one. A flashing red light in one pod means you need to look at another pod to find a flashing liquid crystal that warns of low fuel, or a sidestand down or low oil pressure or low battery fluid. If that isn’t enough, you can push a button that> swings the tach needle into service as a voltmeter. This isn’t even real tinsel. The only possible excuse for the voltmeter is that the Kawasaki can’t be push-started when the battery goes dead, because the neutral finder locks out second gear. Even then, the voltmeter doesn’t help. Another problem is the mirrors. They perch on stubby little stalks at the sides of the fairing where they don’t get in the way of anything. Unfortunately, they are so closely tucked in they are of no use for seeing what’s behind the motorcycle. This is another design shared with the other GPzs, but in this case it’s a hazard to the rider.

The tightly-packed dimensions of the fairing not only limit where the mirrors can go, they also limit where the handlebars can go. So Kawasaki has multipiece handlebars that go in one place only. The position of the bars, pegs and other controls is very good for fast riding. The rider assumes a mild crouch, where he is in control of the bike and isn’t too cramped. For the rider who likes to tailor a motorcycle, the GPz is not so good. The handlebars can’t be easily replaced with a different bend, and the seat-to-pegs distance is short, making this not the perfect touring bike. But that’s okay. Kawasaki makes other bikes for that.

The GPz is built for spirited riding. It steers so quick and so easily you have to adjust to the bike’s reaction times. The suspension is taut and well controlled on all surfaces. It handles bumpy corners especially well. Cornering clearance is all the tires can handle, though the mounting lug on the kickstand might drag under some conditions. That could be a problem because the stand has been moved forward so that it is less dangerous to the rider who leaves the stand down when cornering, though this fix could be more of a problem for the rider who corners with the stand up. The handling is more than responsive, maybe even eager.

The brakes are just as energetic. You’ve heard of two-finger brakes? This thing has one-finger brakes. Maybe even one pinky brakes. A delicate touch is called for to avoid brake lock-up, especially on the back brake. But the control is such that the brakes work. They just work with less pressure than almost any other motorcycle brakes.

When the GPz550 first appeared, it was something of a gamble for Kawasaki. Imitation choppers were selling. Sport bikes, well, nobody much thought about sport bikes. Other mid-size bikes included Honda’s CX500 and Suzuki’s aging GS550. Kawasaki didn’t advertise those first GPzs. They just sort of let them leak out. They were discovered. And now everybody’s got a sporting bike to compete with the Kawasaki.

But the GPz has something the others don’t have. A reputation.

KAWASAKI GPz550

$2899

View Full Issue

View Full Issue