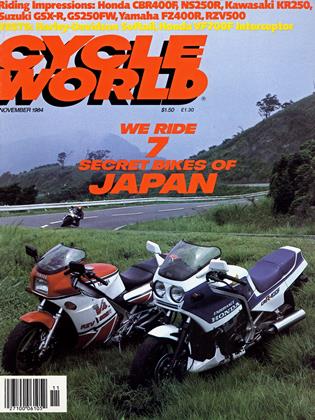

CYCLE WORLD RACE WATCH

They don’t call him Steady Eddie for nothing

KEN VREEKE

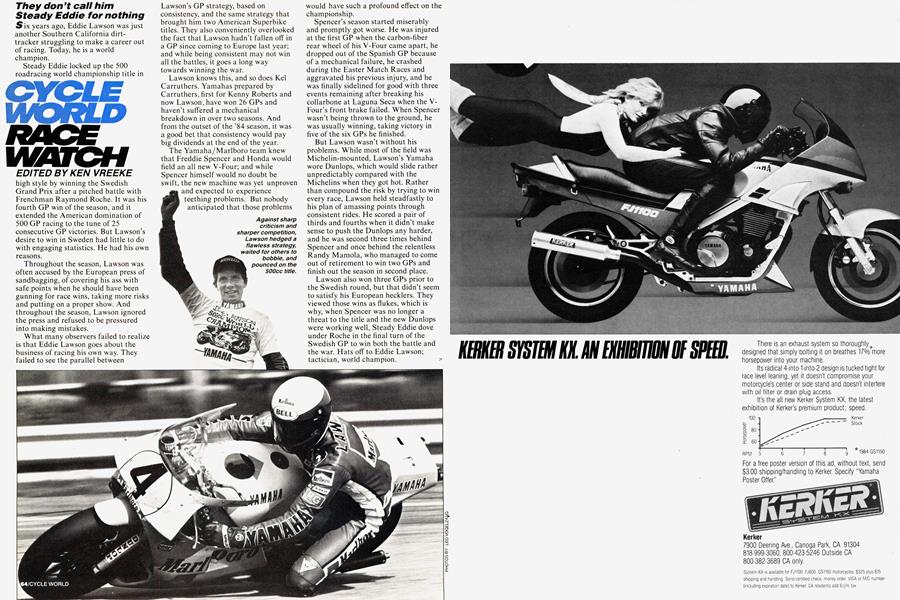

Six years ago, Eddie Lawson was just another Southern California dirttracker struggling to make a career out of racing. Today, he is a world champion.

Steady Eddie locked up the 500 roadracing world championship title in

high style by winning the Swedish Grand Prix after a pitched battle with Frenchman Raymond Roche. It was his fourth GP win of the season, and it extended the American domination of 500 GP racing to the tune of 25 consecutive GP victories. But Lawson’s desire to win in Sweden had little to do with engaging statistics. He had his own reasons.

Throughout the season, Lawson was often accused by the European press of sandbagging, of covering his ass with safe points when he should have been gunning for race wins, taking more risks and putting on a proper show. And throughout the season, Lawson ignored the press and refused to be pressured into making mistakes.

What many observers failed to realize is that Eddie Lawson goes about the business of racing his own way. They failed to see the parallel between

Lawson’s GP strategy, based on consistency, and the same strategy that brought him two American Superbike titles. They also conveniently overlooked the fact that Lawson hadn’t fallen off in a GP since coming to Europe last year; and while being consistent may not win all the battles, it goes a long way towards winning the war.

Lawson knows this, and so does Kel Carruthers. Yamahas prepared by Carruthers, first for Kenny Roberts and now Lawson, have won 26 GPs and haven’t suffered a mechanical breakdown in over two seasons. And from the outset of the ’84 season, it was a good bet that consistency would pay big dividends at the end of the year.

The Yamaha/Marlboro team knew that Freddie Spencer and Honda would field an all new V-Four; and while Spencer himself would no doubt be swift, the new machine was yet unproven and expected to experience teething problems. But nobody anticipated that those problems would have such a profound effect on the championship.

Spencer’s season started miserably and promptly got worse. He was injured at the first GP when the carbon-fiber rear wheel of his V-Four came apart, he dropped out of the Spanish GP because of a mechanical failure, he crashed during the Easter Match Races and aggravated his previous injury, and he was finally sidelined for good with three events remaining after breaking his collarbone at Laguna Seca when the VFour’s front brake failed. When Spencer wasn’t being thrown to the ground, he was usually winning, taking victory in five of the six GPs he finished.

But Lawson wasn’t without his problems. While most of the field was Michelin-mounted, Lawson’s Yamaha wore Dunlops, which would slide rather unpredictably compared with the Michelins when they got hot. Rather than compound the risk by trying to win every race, Lawson held steadfastly to his plan of amassing points through consistent rides. He scored a pair of thirds and fourths when it didn’t make sense to push the Dunlops any harder, and he was second three times behind Spencer and once behind the relentless Randy Mamola, who managed to come out of retirement to win two GPs and finish out the season in second place.

Lawson also won three GPs prior to the Swedish round, but that didn’t seem to satisfy his European hecklers. They viewed those wins as flukes, which is why, when Spencer was no longer a threat to the title and the new Dunlops were working well, Steady Eddie dove under Roche in the final turn of the Swedish GP to win both the battle and the war. Hats off to Eddie Lawson; tactician, world champion.

Bailey doubles up

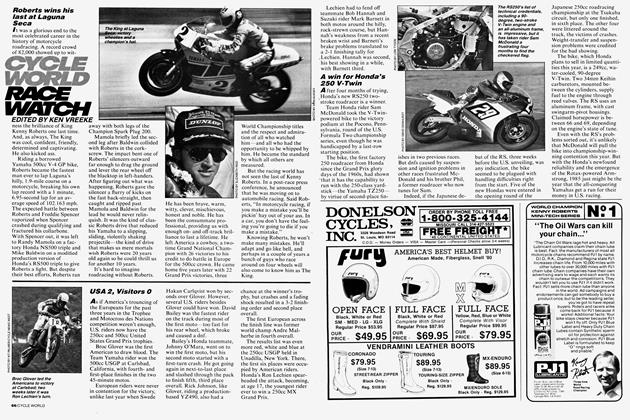

If you were to compile a list of all America’s grand national champions of ^motocross, the list would include only one name. The AMA has awarded the GNC title for just two years, and at the Washougal, Washington, round of the outdoor nationals, David Bailey secured his second consecutive grand national championship.

Even though this is Bailey’s second >GNC, this title means little compared to his first one. Said Bailey, “It’s stupid. But I’m glad I won anyway. The GNC should include all the outdoor races and all the Supercrosses, but this was just the outdoors plus two stadium races.”

That schedule was developed after a /ift between Supercross promoters and the AMA. The result of that conflict was the formation of Insport, the new sanctioning body for most of the stadium races. Only Daytona and Talledega were left to the AMA, and so those were the only two included in the GNC series.

If, in Bailey’s own eyes, that detracts from his GNC title, he feels nothing overshadows his 500 national championship. He took the title convincingly, winning 16 out of 20 motos. And while some would try to detract from that victory, saying that Bailey’s closest competitor, Broc Glover, rode inferior, production-based 'equipment, Bailey dismisses the charges. “I didn’t have an advantage.

He had a disadvantage. Everyone said that my bike was unbeatable. But I had a lot of development to do at first.

Broc’s Yamaha seemed better on bottom end. All I had was a top-end ^advantage, and not all the tracks were top-end tracks.”

Bailey adds this year’s 500 championship to the 250 crown he earned last year, joining Kent Howerton, Marty Smith, Broc Glover and Bob Hannah as a rider who has earned championships in two outdoor classes.

Two other riders claimed national titles in Washington, but for each rider it was his first AMA championship win. And for each rider it was a close battle. Rick Johnson took his production-based ,YZ250 to Washougal with only a threepoint advantage over Honda’s Ron Lechien. Lechien, you might recall, stepped out of his Yamaha contract last year because he felt he couldn’t be competitive on the production-based machines. Johnson, however, was more ^than competitive on the YZ. He beat Lechien in Washington to win the 250 national championship, a title he narrowly missed two years ago when Donnie Hansen edged him out by three points.

Jeff Ward has narrowly missed his share of championships, too, but not this year. He dethroned Johnny O’Mara in the 125 class by winning 13 motos to O’Mara’s 7. No other riders were even

close. This marks Kawasaki’s first national motocross title since Jimmy Wienert won the 500 class in 1974. In

fact, this is the first time in seven years that the three outdoor titles were won by three different manufacturers. This, despite wildly different approaches from the four biggest competitors; Honda with its high-dollar factory team, Yamaha with its production bikes, and Kawasaki and Suzuki with lean but effective efforts.

All of which goes to show that when it comes to motocross, there are no exact formulas for winning. And there are never any guarantees.

Riding the road to Camel Pro points

While the attention of most AMA Camel Pro Series fans is riveted on the battle royale between HarleyDavidson’s defending champ Randy Goss and Team Honda’s Ricky Graham, there’s another story brewing 40 points back of the leaders in third place.

That’s where you’ll find Doug Chandler, Team Honda’s 19-year-old whiz-kid who turned Expert last year and finished 16th in the points chase, good enough for Rookie of the Year honors. This year, Chandler finds himself in a better position because he has made his CPS points the oldfashioned way: He’s earned them, on both the dirt tracks and the roadrace courses.

You have to go back 10 years to the championship-winning days of Kenny Roberts to find a rider who used points gathered in roadracing to win the grand national championship. Since then the title has been won almost exclusively with dirt-track points. Indeed, most of the front-line dirt guys don’t even set foot on asphalt anymore, saying that aspect of the sport is too specialized and, more importantly, too expensive.

For the potential points earned, it’s simply not worth the effort in time and money.

Unless, of course, you happen to be in charge of the race program at Honda. Honda, you see, desperately wants to win the grand national championship, and a few points won on pavement can mean the difference between a bike that carries the Number One plate and one with a lesser digit affixed.

And so it came to pass that Honda outfitted its entire dirt-track team of Ricky Graham, Bubba Shobert and Doug Chandler with 850cc endurancerace-engined Superbikes that are perhaps not as competitive as Mike Baldwin’s RS500 two-stroke V-Three, but certainly easier to ride. After all, it wasn’t wins these guys were after, just bonus points.

By far the most successful gatherer of those points has been Chandler. In the three F-l roadraces he has entered— Loudon, Pocono and Sears Point— Chandler has finished 12th, 6th and 5th, respectively, for a total of 22 points, which have helped move him five points

ahead of Harley’s Scott Parker in the overall standings with two more roadraces still to go.

While Chandler has been on the road to a substantial number of points, Shobert has failed to finish a race; and Graham, after a fall at Loudon, seems to be a little gun-shy and has stayed on the dirt tracks. It remains to be seen if Graham will risk another crash for a few precious points or let his dirt-track riding do the talking.

That Chandler is the fastest of the three is no surprise to Keith Code, a sort of roadrace svengali who runs the California Superbike School and has tutored the likes of Eddie Lawson, Wes Cooley and Wayne Rainey. Honda hired Code to teach its flat-trackers a thing or two about apexes and kneedragging, but Code already knew about Chandler. The year before, the youngster had attended the Superbike School at Laguna Seca, and promptly turned the fastest lap ever for a firsttime student. “He had that winner’s gleam in his eyes,” Code remembers, “You couldn’t miss it.”

Other people have seen that gleam in Chandler’s eyes as well. One observer has already said that Chandler’s talent is “awesome” and that next year he just might be “unbeatable.” The speaker? None other than Chandler’s Honda teammate, Ricky Graham.

Race Watch Calendar 1984

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle World Editorial

Cycle World EditorialOf Myths And Mystiques

November 1984 By Paul Dean -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

November 1984 -

Cycle World Roundup

Cycle World RoundupThe 15 Million Dollar Motorcycle

November 1984 By David Edwards -

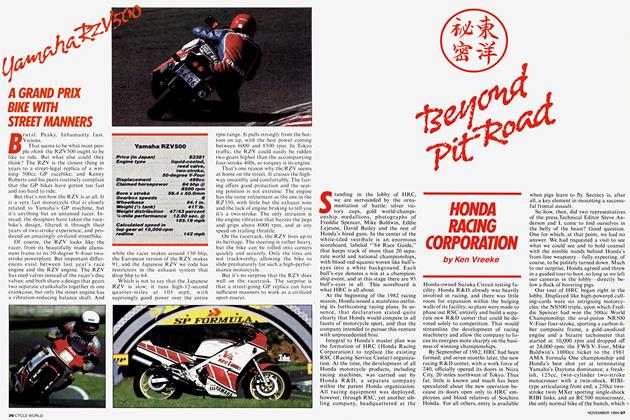

Special Section

Special SectionBeyond Pit Road

November 1984 By Ken Vreeke -

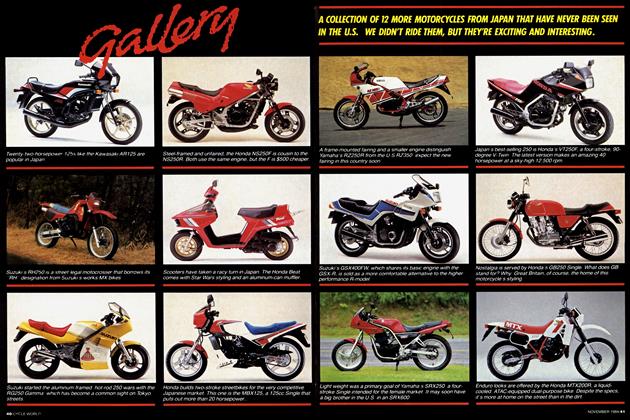

Special Section

Special SectionGallery

November 1984 -

Special Section

Special SectionThe Tokyo Grand Prix

November 1984