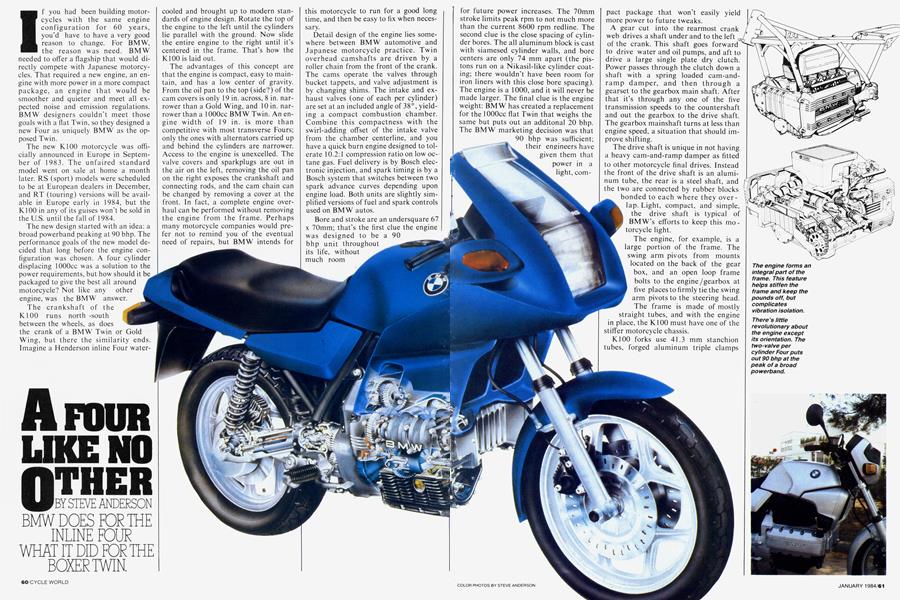

A FOUR LIKE NO OTHER

BMW DOES FOR THE INLINE FOUR WHAT IT DID FOR THE BOXER TWIN.

STEVE ANDERSON

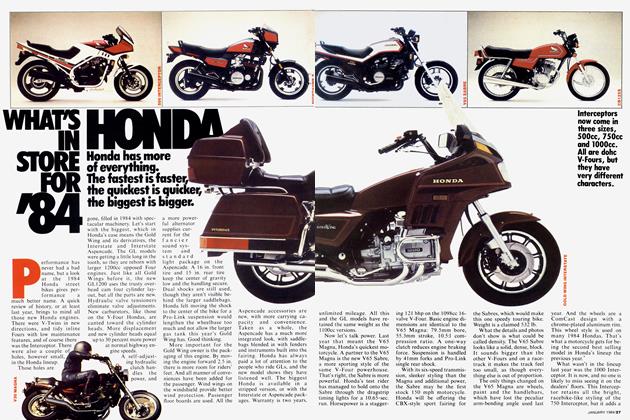

If you had been building motorcycles with the same engine configuration for 60 years, you’d have to have a very good reason to change. For BMW, the reason was need. BMW needed to offer a flagship that would directly compete with Japanese motorcycles. That required a new engine, an engine with more power in a more compact package, an engine that would be smoother and quieter and meet all expected noise and emission regulations. BMW designers couldn’t meet those goals with a flat Twin, so they designed a new Four as uniquely BMW as the opposed Twin.

The new K100 motorcycle was officially announced in Europe in September of 1983. The unfaired standard model went on sale at home a month later. RS (sport) models were scheduled to be at European dealers in December, and RT (touring) versions will be available in Europe early in 1984, but the K100 in any of its guises won't be sold in the U.S. until the fall of 1984.

The new design started with an idea: a broad powerband peaking at 90 bhp. The performance goals of the new model decided that long before the engine configuration was chosen. A four cylinder displacing lOOOcc was a solution to the power requirements, but how should it be packaged to give the best all around motorcycle? Not like any other engine, was the BMW answer.

The crankshaft of the K100 runs north -south between the wheels, as does the crank of a BMW Twin or Gold Wing, but there the similarity ends. Imagine a Henderson inline Four watercooled and brought up to modern standards of engine design. Rotate the top of the engine to the left until the cylinders lie parallel with the ground. Now slide the entire engine to the right until it’s centered in the frame. That’s how the K100 is laid out.

The advantages of this concept are that the engine is compact, easy to maintain, and has a low center of gravity. From the oil pan to the top (side?) of the cam covers is only 19 in. across, 8 in. narrower than a Gold Wing, and 10 in. narrower than a lOOOcc BMW Twin. An engine width of 19 in. is more than competitive with most transverse Fours; only the ones with alternators carried up and behind the cylinders are narrower. Access to the engine is unexcelled. The valve covers and sparkplugs are out in the air on the left, removing the oil pan on the right exposes the crankshaft and connecting rods, and the cam chain can be changed by removing a cover at the front. In fact, a complete engine overhaul can be performed without removing the engine from the frame. Perhaps many motorcycle companies would prefer not to remind you of the eventual need of repairs, but BMW intends for this motorcycle to run for a good long time, and then be easy to fix when necessary.

Detail design of the engine lies somewhere between BMW automotive and Japanese motorcycle practice. Twin overhead camshafts are driven by a roller chain from the front of the crank. The cams operate the valves through bucket tappets, and valve adjustment is by changing shims. The intake and exhaust valves (one of each per cylinder) are set at an included angle of 38°, yielding a compact combustion chamber. Combine this compactness with the swirl-adding offset of the intake valve from the chamber centerline, and you have a quick burn engine designed to tolerate 10.2:1 compression ratio on low octane gas. Fuel delivery is by Bosch electronic injection, and spark timing is by a Bosch system that switches between two spark advance curves depending upon engine load. Both units are slightly simplified versions of fuel and spark controls used on BMW autos.

Bore and stroke are an undersquare 67 x 70mm; that’s the first clue the engine was designed to be a 90 bhp unit throughout for future power increases. The 70mm stroke limits peak rpm to not much more than the current 8600 rpm redline. The second clue is the close spacing of cylinder bores. The all aluminum block is cast with siamesed cylinder walls, and bore centers are only 74 mm apart (the pistons run on a Nikasil-like cylinder coating; there wouldn’t have been room for iron liners with this close bore spacing). The engine is a 1000, and it will never be made larger. The final clue is the engine weight: BMW has created a replacement for the lOOOcc flat Twin that weighs the same but puts out an additonal 20 bhp. The BMW marketing decision was that 90 bhp was sufficiënt; their engineers have given them that power in a light, compact package that won’t easily yield more power to future tweaks.

A gear cut into the rearmost crank web drives a shaft under and to the left of the crank. This shaft goes forward to drive water and oil pumps, and aft to drive a large single plate dry clutch. Power passes through the clutch down a shaft with a spring loaded cam-andramp damper, and then through a gearset to the gearbox main shaft. After that it’s through any one of the five transmission speeds to the countershaft and out the gearbox to the drive shaft. The gearbox mainshaft turns at less than engine speed, a situation that should improve shifting.

The drive shaft is unique in not having a heavy cam-and-ramp damper as fitted to other motorcycle final drives. Instead the front of the drive shaft is an aluminum tube, the rear is a steel shaft, and the two are connected by rubber blocks bonded to each where they overlap. Light, compact, and simple, the drive shaft is typical of BMW’s efforts to keep this motorcycle light.

The engine, for example, is a large portion of the frame. The swing arm pivots from mounts located on the back of the gear box, and an open loop frame bolts to the engine/gearbox at five places to firmly tie the swing arm pivots to the steering head. The frame is made of mostly straight tubes, and with the engine in place, the K100 must have one of the stiffer motorcycle chassis.

K100 forks use 41.3 mm stanchion tubes, forged aluminum triple clamps top and bottom, and sliders that are extra wide at the bottom and grip the axle with double pinch bolts. The axle is nearly one inch in diameter and hollow, and when clamped in place it contributes to an extremely stiff front end. That's a welcome change from the older BMW forks, which are among the more flexible. The new forks maintain the BMW tradition in having plenty of travel (7.3 in.), and weigh no more than the old ones.

Rear suspension is by a derivative of the single-sided swing arm first used on the R80GS. This time the swing arm is cast aluminum and connects to a single deCarbon type shock on the right side of the bike. Wheel travel is about 4.4 in., slightly less than used on previous BMWs. Concerned about swing arm flex with a single sided arm? BMW engineers assure us it isn’t a problem, and the R80GS and ST have worked well.

When all these parts are put together into a motorcycle, it turns out to be extraordinarily light. The standard KlOO weighs a claimed 510 lb. with half a tank of gas, the RS version 532 lb., and the RT 543 lb. Think of that— a watercooled, lOOOcc, shaft drive four cylinder touring bike, with full fairing and saddlebags, that weighs about the same as a sporting 750.

The shapes given to the KlOO are clean and more than a little reminiscent of the Suzuki Katana. Which isn't too surprising as Hans Muth, the Katana’s designer, came from the same BMW styling department as the K 100’s designers.

Even the unfaired model spent time in the wind tunnel, resulting in changes to the headlight pod. The faired models were thoroughly shaped by lessons learned in the tunnel, and the KIOORS offers less drag and lift than the standard KlOO while (according to BMW) maintaining the same amount of rider protection as the twin cylinder RS. The new RT fairing is larger and designed around higher and wider handlebars. Even so,, it’s claimed to have no more drag than the unfaired KlOO with the rider sitting upright.

The KlOO in metal appears more purposeful and compact than in photographs. The surprising thing is to park it next to a R100 Twin, and find that the new bike is the smaller of the two. There isn’t a rough edge or thoughtlessly executed part on the KlOO; it looks functional and expensive, just as its designers intended.

Swing a leg over the KlOO, and the bike feels tall, as the 32 in. seat height might indicate. The pegs are further back than on other BMWs, and the bars on the standard KlOO are a bend that leaned me forward slightly and placed my hands in a comfortable position. The bike fits well.

The instruments share a pod with the headlight, and consist of simple dial type tach and speedo. Digital displays are limited to a gear indicator and clock. There are the usual warning lights, and „instead of a fuel gauge, there are lights that tell when the fuel supply is down to the last two gallons, and then the last one.

Switch gear is new and different, continuing a BMW tradition of innovative placement. These switches may start another tradition: innovative switch locations that are actually an improvement over standard layouts. Large buttons on the right and left switch clusters start the turn signal flashes. Push the right button down with your thumb, the right signal flashes. Ditto for the left button and signal. Unlike a Harley, though, you don’t have to hold the button down. The signals flash at the first touch, and then self-cancel later. Or there’s a button to cancel the flashing if you round a turn before the electronics give you credit.

The engine starts easily, the ‘choke’ control on the handlebars acts only as a fast idle position. Mixture enrichment is handled by the fuel injection. Blip the throttle, and the quick-revving Four tells you this is not your ordinary BMW. No torque reaction, either. The counter-rotating clutch and alternator cancel that, and the bike doesn’t try to lean when the engine accelerates.

Accelerate is something the K100 does well. The engine makes solid lOOOcc Four power, and the K100 hustles down the road like no BMW before. The clutch is light and positive, and the gearbox is superb, crunchless and quick shifting.

The power train, despite its exotic layout, invites comparisons. The exhaust note, and the gear noises coming from the engine, shout, ‘inline Four.’ So does the engine vibration which buzzes the footpegs at certain rpm. The engine character is a dead ringer for any number of Japanese Fours, at least those that are solidly mounted in their frames. Rubber mounted Fours are smoother running than the K100.

Steering is light and quick, very stable. The ride is well controlled without transmitting jarring forces to the rider. The front end dives under hard braking, but doesn’t bottom. The bike builds confidence. Nothing drags except the footpegs during hard street riding, and even the dreaded shaft drive rise and fall is largely unnoticable.

Braking feels similarly good, at least in front. The front Brembo calipers offer good feel and stopping power without being too sensitive. The rear brake linkage has a block of rubber added to it, to help control a rear wheel chatter problem under hard braking. The brake feels, well, rubbery, and the chatter problem hasn’t been entirely eliminated.

Over the 36 mile test loop BMW had set up in France, the unfaired K100 was most comfortable over the twisty, secondary road sections. On the Autoroute, the upright riding position was a pain at the 100 mph-fspeeds that were possible. The aggressive sports fairing on the K100RS was the cure for that, and made life acceptable at the 135 mph speed the RS would indicate. There were drawbacks, however. The narrower bars on the RS increased steering effort, and the unique bi-plane spoiler fitted to the top of the windshield served only to increase helmet buffeting. Nor did the fairing live up to BMW’s claim of matching the level of protection provided by the twin cylinder RS fairing. The new smaller fairing gives increased buffeting of the rider’s arms, and hot air from the radiator heated the legs while riding the RS on the Autoroute; this wasn’t the case with the standard K100.

The larger fairing of the RT looked as if it might eliminate the relatively minor shortcomings of the RS fairing, but unfortunately it wasn’t available for test rides.

Availability may be the worst problem with the entire K100 series. None will be sold in the U.S. until the fall of 1984, then they’ll be sold as 1985 models. BMW expects the price to be slightly higher than the comparable lOOOcc Twins. That would put the standard K100 somewhere over the R 100’s $5300 tag, the K100RS over $6900, and the K100RT over $7400. U.S. models will come with slightly different fuel injection calibration, but no other engine changes. They’ll also have a non-springloaded side stand, a feature deleted at the insistence of Jean-Pierre Bailby, who runs the BMW importing operation in the U.S. Thank you, Jean-Pierre.

The BMW model line up for the U.S. in 1984 is exactly the same as for 1983: the opposed Twin in 1000, 800, and 650cc displacements in the same range of street, sport, touring, and exploring models offered before. Devotees of the Twins have no reason to worry about the years after that. BMW envisions the Twin continuing in production indefinitely in displacements up to 800cc. Engine and chassis improvements are in the works as well, and future BMW Twins should reflect the lessons learned from the K100 project.

The K100 is an important motorcycle. It’s an European bike that competes head on against the Japanese with no excuses. The K100 represents the corporate soul-searching that BMW went through during the late 1970s and the conclusion that came from it: BMW will never abandon the motorcycle. With the K100, there should be no need to. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue