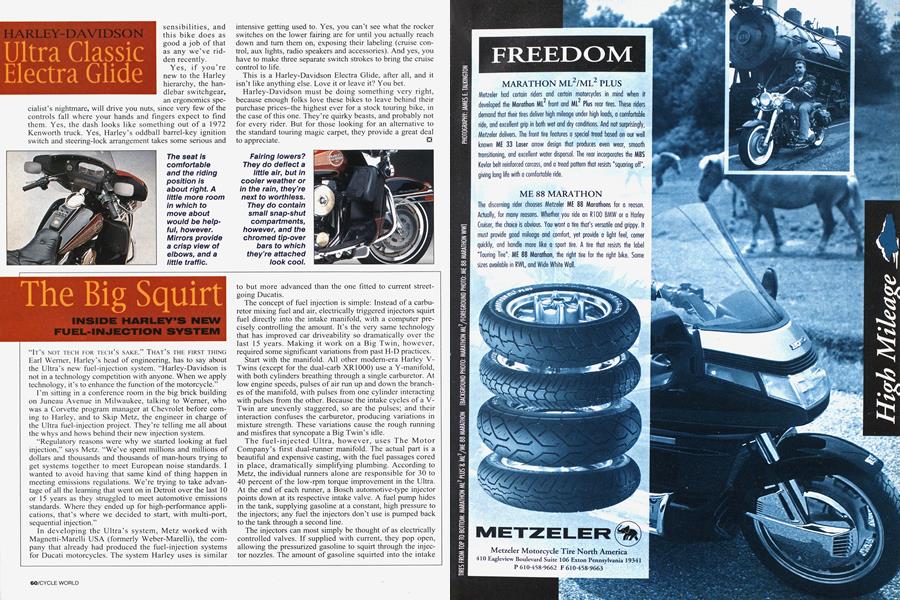

The Big Squirt

INSIDE HARLEY'S NEW FUEL-INJECTION SYSTEM

“IT’S NOT TECH FOR TECH’S SAKE.” THAT’S THE FIRST THING Earl Werner, Harley’s head of engineering, has to say about the Ultra’s new fuel-injection system. “Harley-Davidson is not in a technology competition with anyone. When we apply technology, it’s to enhance the function of the motorcycle.”

I’m sitting in a conference room in the big brick building on Juneau Avenue in Milwaukee, talking to Werner, who was a Corvette program manager at Chevrolet before coming to Harley, and to Skip Metz, the engineer in charge of the Ultra fuel-injection project. They’re telling me all about the whys and hows behind their new injection system.

“Regulatory reasons were why we started looking at fuel injection,” says Metz. “We’ve spent millions and millions of dollars and thousands and thousands of man-hours trying to get systems together to meet European noise standards. I wanted to avoid having that same kind of thing happen in meeting emissions regulations. We’re trying to take advantage of all the learning that went on in Detroit over the last 10 or 15 years as they struggled to meet automotive emissions standards. Where they ended up for high-performance applications, that’s where we decided to start, with multi-port, sequential injection.”

In developing the Ultra’s system, Metz worked with Magnetti-Marelli USA (formerly Weber-Marelli), the company that already had produced the fuel-injection systems for Ducati motorcycles. The system Harley uses is similar to but more advanced than the one fitted to current streetgoing Ducatis.

The concept of fuel injection is simple: Instead of a carburetor mixing fuel and air, electrically triggered injectors squirt fuel directly into the intake manifold, with a computer precisely controlling the amount. It's the very same technology that has improved car driveability so dramatically over the last 15 years. Making it work on a Big Twin, however, required some significant variations from past H-D practices.

Start with the manifold. All other modern-era Harley VTwins (except for the dual-carb XR1000) use a Y-manifold, with both cylinders breathing through a single carburetor. At low engine speeds, pulses of air run up and down the branches of the manifold, with pulses from one cylinder interacting with pulses from the other. Because the intake cycles of a VTwin are unevenly staggered, so are the pulses; and their interaction confuses the carburetor, producing variations in mixture strength. These variations cause the rough running and misfires that syncopate a Big Twin’s idle.

The fuel-injected Ultra, however, uses The Motor Company’s first dual-runner manifold. The actual part is a beautiful and expensive casting, with the fuel passages cored in place, dramatically simplifying plumbing. According to Metz, the individual runners alone are responsible for 30 to 40 percent of the low-rpm torque improvement in the Ultra. At the end of each runner, a Bosch automotive-type injector points down at its respective intake valve. A fuel pump hides in the tank, supplying gasoline at a constant, high pressure to the injectors; any fuel the injectors don’t use is pumped back to the tank through a second line.

The injectors can most simply be thought of as electrically controlled valves. If supplied with current, they pop open, allowing the pressurized gasoline to squirt through the injector nozzles. The amount of gasoline squirted into the intake tract is determined by how long the current is supplied to the injectors: The longer they’re open, the more gasoline the engine gets.

All of this is determined by a black box-the ECU, for engine control unit-which somehow must know how much fuel to give the engine at any time. There are several different ways to do that, but the Weber-Marelli system uses one of the simplest: a map. At any given instant, sensors tell the ECU the current crank position, rpm, cylinder-head temperature, intake-air temperature, throttle position and air pressure; then, depending on those variables, the ECU looks up on the map when to open each injector, how long to leave it open, and when to fire the sparkplugs.

Throttle position and rpm are the primary variables of the ECU’s map. The other measured variables are used to tweak these basic settings for best performance under dynamic conditions. Opening the throttle quickly, for example, causes the fuel How, as determined by the map, to be increased by a specific percentage for the best response.

Where did the Ultra’s map come from? Long weeks and months of dyno testing at Harley and Magnetti-Marelli, that’s where. The engineers held the engine at a specific rpm and throttle opening while ignition timing and injection duration were varied until the torque reading-with acceptable exhaust emissions, of course-reached its peak, then those settings were recorded. The engineers then moved on to the next rpm and throttle position, again and again and again, until they likely woke up trembling at night any time they heard a Big Twin rumble by.

The map approach has another significant drawback, as Metz readily admits: It is only appropriate for one specific state of engine tune. “Anything that changes volumetric efficiency will affect the way the bike runs. There’s enough flexibility to allow a change in mufflers, and you won’t notice the difference. But try changing the cam ...” he says, shaking his head and not finishing the sentence. Which means that if you buy an injected Electra Glide Ultra, you’d better be completely happy with its stock performance.

Most touring riders will be satisfied. The bike’s cold-start characteristics are especially rewarding; it’s ready to ride away almost as soon as the starter button is pushed. As Metz says, the injection is “a way to give the government what they need, or will need in the near future, and still give the customer what he needs. For example, this system allows us to give a California customer better performance than with a standard, 49-state bike.”

And how about the Ultra’s smooth idle? Says Werner, “If you take a conventionally carbureted Harley and let it idle for a while, it'll develop into this sporadic cadence that is characteristic of the breed, as one cylinder loads up-or maybe it’s EGR (exhaust-gas recirculation) crosstalk causing it. This bike doesn’t do it. One thought that was going through some minds here was to program in a random misfire just so it would sound like a real Harley.” With that mention of inefficiency by design, Werner laughs out loud.

“We have data on carbureted Harleys that shows they misfire at idle one or two out of every 10 engine cycles,” adds Metz. “We asked Weber if they could do that. But they had to take out so many injection pulses just to notice a difference ...” His voice trails off as he shakes his head once again.

There are times, then, when progress extracts its price. If you’re a traditionalist, this could well be one of them.

—Steve Anderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOklahoma Hits Home

August 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGood Company

August 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThunder Bolts

August 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupBritten To Build Indians

August 1995 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupBikes Will Be Made In the Usa, Says Indian's New Chieftain

August 1995 By Alan Cathcart