Heartfelt Highways

Tales from Granny’s Grocery Our Lady of the Butane Tank and the Elephant Ride.

Wade Roberts

It was into Hopeful, Georgia, that Highway 65 spilled me, cold, wet, lonely and less than. The day was mud-dreary, a drab smudge of a Monday that had dawned with more of a shrug than a sunrise. After losing a couple of skirmishes at daybreak, the sun had surrendered, sliding behind a low haze. A listless afternoon rain fell in limp sheets, shedding a chill everywhere it splashed. As days go,

this one had been dealt from somewhere near the bottom of the deck.

I was well into the third day of a rambling, back-roads motorcycle trip through my native South, slicing a razor-line deep into the heart of Dixie.

I'd gone back because I was homesick.

Six months earlier, I had moved to Southern California. Suddenly, I was living in a world of Porsches, BMWs, Rolls-Royces and vanity plates, instead of pickup trucks with gun racks and tobacco-spit stains down the driver’s door. Of sushi, artichokes and avocadoes instead of chicken-fried steak, collard greens and yams. Of restaurants with “non-smoking ambiances,” instead of cafes where Winston-dangling waitresses shuffled over with a “What'll it be, hon'?” Of bumper stickers that said No Nukes, instead of Eat More Rice. Of people who said “Have a nice day,” instead of “ Y’all come back now, y’hear?”

What I missed was this: drawls, water towers, honky-tonks, icehouses, tent revivals, red dirt roads, magnolias, southern blues, tissue-wrapped cans of Jax beer, travel courts with Magic Fingers beds, playing “Pop A Top, Again” on the jukebox, five plays for a quarter. But what I missed most of all, were the people: friendly, sincere, honest, open, easygoing.

And now, now that I was back, I was' still homesick. Because I knew I had to leave again.

I was lost in thought when I pulled into a Hopeful diner. I ordered a cup of coffee and hunkered down, gazing outside at the Harley. An old fellow sidled up from across the room. Butch, he said his name was. “How yew?” he asked.

“Livin',” I answered.

“You livin' in these parts?”

“No sir,” I said, “Born and raised in the South, but I'm livin' out West now.”

“Well, welcome back, boy. Why so down in the mouth?”

“‘Cause I have to leave again.”

“Now, son, you got to 'speet a little heartbreak when you go leavin' a place,” Butch said. “You know' what they say. Home is where the heart is.”

I began in Daytona Beach, Florida, at the tail end of Speed Week. Ed arranged to borrow a nice, new, shiny-red Harley-Davidson FXRT from the nice folks in Milwaukee. Because of this and that, the little last-minute things that accompany the start of long trips, it was late afternoon before I got out of town.

A raveled country road ushered the Harley through gradually thinning woods into Florida's flatlands. Exacting rows of citrus trees, as scrupulously pruned as toy poodles, replaced the lanky, unruly pines. The darkening sky seemed to have sagged, nothing supporting it now but the generally accepted belief that Chicken Little had been wrong.

On the map, a name caught my eye and roused my curiosity. Snowhill, Florida. Did it ever snow in Snowhill? There was no sign of snow in Snowhill. There also was no sign of Snowhill. The hill part was debatable. All there was, was a streetsign Snowhill Road, it said and an unpromising sliver of pave-, ment that slipped into the twilight, then disappeared. Had it ever existed, peopled, hustling, bubbling, alive? Or was the town only the stillborn offspring of some developer’s vision'.’ In either case, there was nothing left but another ragged dream that had long ago faced its dawn. A roadmap was its final resting place.

I didn’t stop until I had to, for a tank of gas. Near Chuluota, I homed in on a twinkling green light and Granny's Grocery / Jazz Feeds / Self-Service Gas. On the business end of the cash register was a grayhaired woman. Granny? I decided not to take the chance, and swallowed the question. Once, at another Granny’s in another state, I had asked. Not only was she not a grandmother, the woman had grumped, her oldest child was only seven. She had added that she had just graduated from a junior college martial arts class, and was I interested in having my presumptuous butt whupped?

South of Kissimmee, I decided that I was in the market for a place to stay the night. Trouble was, there wasn't much of a market. U.S. 441 was in no danger of overdevelopment; mile after mile, it barreled through the night, dark, desolate, deserted.

Then, in shimmering red and green neon letters as high as a man, an irresistable proposition beckoned: MOTEL BAR GOOD FOOD DESERT INN. It was mecca, as far as I was concerned. Gas pumps in front, diner and bar inside, travel court out back, the Desert Inn squatted alongside U.S. 441, where it met State 60. Yeehaw Junction, the crossroads was called.

A room was $13.55, cash, no credit cards; $14.80, and the room came with a color TV. I splurged and took the TV, then sat down at the diner counter and ordered a hamburger and a beer.

A couple of stools over, a good ol’ boy truckdriver slumped before a bourbon, his head rising like a gimme-capped mountain peak through a cirrostratus cloud of Lucky Strike smoke. He had engaged himself in a one-man discourse on current events.

“Damn politicians. Ain’t none of them sumbitches worth a hoot,” he mumbled to the glass. “Even the presidents. Ain’t had a good one since Hoover.”

“Hell, maybe you oughta run,” I offered.

His brow creased as he considered a bid for the highest office in the land. “Why not?” he finally said. “Where do I sign up?”

“Right here,” said the waitress, setting down his bill.

In the room, I turned on the TV. It was color, all right. Purple. After a while, I gave up and flipped through a newspaper I’d picked up earlier. Here’s what I learned: “A Casselberry woman spent two nights in the woods when she became lost while looking at some property.” And, “Bob Collins is the poet laureate of Goldenrod. He won that title many years ago with his humorous rhymes on his outdoor sign.”

Filled in on the news, I climbed into bed. At a truck stop across the way, a chorus of air wrenches clattered, singing me a lullaby of the road.

The diner was crowded the next morning and most of the booths were occupied, so I sat at the counter and ordered eggs and grits. While I waited, I puzzled over a hand-scrawled sign taped next to a rack festooned with bags of fried pork rinds and four kinds of Slim Jims. The sign said YCHJCYAHFTJB.

“Stands for Your Curiosity Has Just Cost You A Half-dollar For The Jukebox,” explained Bill McCarthy, owner of the Desert Inn. He offered to change a dollar for me, should I need it. I did.

Before I could reach the jukebox, it was hijacked by a cute, tight-jeaned, cowboy-hatted young woman, the kind that singers of country songs are always pining for and fighting over. “I fell for the sign,” I confessed, feeding in two quarters. “My treat.”

“You did, huh?” she said, looking up. She had a smile as broad as her Stetson. “Sure hope you like country music.” Her fingers flew. A6. L7. F3. D2. “Oh, Debi Joy Mosier’s my name,” she said.

On the jukebox, Willie Nelson started singing about the last thing he needed the first thing this morning. Debi Joy rocked on the heels of her boots and hummed along to the done-him-wrong tune. As the jukebox played, we talked about who done whom wrong in what song. After an hour or so, I settled up for breakfast and headed out. At the door, Debi Joy said goodbye and handed me something. It was a folded paper napkin.

I waited until I was outside before I opened it. “Thanks for the smile and memory,” it said. Damn, I thought. That should’ve been my line.

A forgotten secondary highway carried me west across the Perma-Press countryside of Florida’s inland plains, flat, but lush with promise. Right below the surface hid a vast water table that fed wide expanses of evergreen grass. In places, the water pooled above-ground in mucky, palmetto-ringed marshes. Where it encountered those bogs, the highway simply rose up a foot or so on trucked-in fill and cut through unhindered.

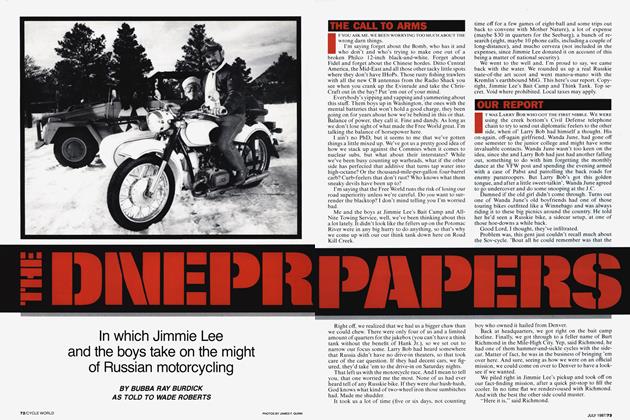

Snicked into fifth, the Harley skimmed over the unbroken pavement, throttle cracked to about 50 mph. Behind the fairing, it was calm and peaceful. The Bo Diddley beat of the exhaust swept somewhere behind me, scattering great-winged white herons in its wash. I was wafted along, breezing, nipping at the heels of possibility.

In Frostproof, Florida, I stopped at a convenience store for gas and an answer to the question I had as soon as I saw the city limits sign. “Ever freeze here?”

I asked the young woman who took my money.

“You kidding? Every winter or there-abouts.”

“But the name ...”

“Someone over at the Chamber of Commerce prob’ly come up with it,’’she said.

Lake Hellen Blazes, Chunky Pond, Upthegrove Beach, Fisheating Creek. The same person responsible for Frostproof must have had something to do with the names of Florida’s inland bodies of water. My own favorite was Lake June in Winter. It was near there, along U.S. 27, that a billboard invited me to “Come Live in Golfland!” How inconvenient, I thought. Someone would always be at the door, wanting to play through.

In search of cigarettes, I detoured at the sign for Venus, and pulled in at the, surprise, Venus Grocery. “Bet you could tell me something about this place,” I said to the only other shopper, an old woman of about 80. Her face was drawn, and as creviced as a stripmined bluff.

“Nawsir, you’d need an old-timer for that,” she answered in a quivering voice. She must have sensed that I was surprised. “Naw, older'n me, like ’round a hunnert-fifty or so. But don't think there’s none of them around.”

“Could you hazard a guess?” I said.

“Well, I could venture one, I ’spose, but don’t go taking it as the gospel,” I had to nod yes before she'd continue. “Now, I don’t think it’s named after no person, 'cause I never heard tell of no one named Venus, not ’round these parts. Myself, I ’speet the Indians named it. They used to travel by the stars, I think. And ain’t there one of them star places named that?”

Yeah, I said, it was something like that.

I couldn’t find a corkscrew in Corkscrew, Florida. But a little ways north of there, I had a chance to ride an elephant. The opportunity presented itself suddenly. I was riding along, horizon-hypnotized, still shy of the middle of nowhere, hoping a possum would waddle out of the brush for some excitement, when without warning ELEPHANTS, THREE OF THE DAMN THINGS, RIDE ’EM, FEED ’EM!

I had stumbled upon Bob Lewiston’s place. Bob and the elephants work with a traveling circus about six months out of the year. During the off-season, he stakes the elephants beside his house and puts up his roadside signs. “Just tryin' to make a little pocket money,” he said. “Otherwise, the elephants would just be standing around.”

Which seemed to be exactly what they were doing. I started to point that out, but Bob stopped me. “Hear that?” he asked. It was the sound of approaching tires. Out on the highway, a dreadnaught of a station wagon, Buick class, steamed all ahead full toward Tampa Bay. It drew even, then passed. “Watch this,” Bob instructed.

A hundred yards down the road, the wagon swerved wildly, bore down on the shoulder and came to a tire-singeing halt. “Delayed reaction,” Bob said. “Happens all the time. Takes a while for the sight to register.”

“Been wondrin”' I said. “This pretty good elephant country, is it?”

“Naw. Cattle. This is cattle country,” he said.

“Ever thought about raising any?”

Bob rolled his eyes and spat. “Now boy,” he said slowly, “just who the hell you suppose is going to pay good money to ride a cow?”

Chasing a confusing series of backroads, I gave wide berth to Tampa-St. Petersburg, the self-proclaimed Gold Coast. Obviously, the chamber had been busy there, too. North of the urban overflow, I turned onto U.S. 19, which veered inland from the Gulf of Mexico into leisurely, almost reluctant slopes of rangy hardwoods. Dusk was approaching, and lights were beginning to come on in the ramshackle houses that dotted the roadbanks every now and then.

I spent the night in Cedar Key, in an old boarding house that had been converted into a hotel. There were only 10 rooms, the bartender-doubling-as-deskclerk said. Somehow, though, I ended up in Room 33; I never figured that out. The cafes on the tiny key were already closed, and I ended up at a no-name bait camp/fisherman’s bar. It was the kind of place where, when the waitress says your table is ready, she’s talking about a pool table. I ate a pound of boiled shrimp and lost $10 playing low-stakes pool. The other players said they were sorry to see me leave.

As it turned out, I got into Haylow, Georgia, a couple of days late for the volunteer fire department’s weekly bingo game (“Every Sat. Nite”) and a few days early for the VFW pancake supper (“All You Can Eat $1.50, Children .75”) and Doris Potter’s yard sale (“Come By Round 10”).

I could’ve bought a pit bull pup, though. “Only $30 A Piece,” the sign said. “Good blood line,” said the seller. Six-foot-ten and 280 lb., at least, scarspangled face, gap-toothed, bloodshot eyes, a fistflattened nose, he looked like a lion-tamer who’d entered the cage one too many times. The six pups rolled and hopped and yammered, warm, soft and cuddly. “Champs, them cute little things are,” the man said. “Them’ll grow into real killers.”

Sparse little settlements lined the blacktop roads, paint-poor wooden shacks tucked under flourishes of skyscraping pines. Then the houses disappeared and the woods closed in until I was riding in a tunnel, cloaked by a jungle-thick quilt of pine, oak, magnolia and Spanish moss. The pavement was bordered by frenzied tangles of kudzu, a Japanese vine that was imported into the South for ground cover. In its new environment, though, kudzu grew so explosively fast that it became a nuisance. It is said that, at night, you can hear the kudzu creeping. That’s not far from the truth; every so often, I'd spot the outline of a rotting barn, or abandoned car, or forgotten boxcar that had been overtaken by the vine.

I moseyed along that lazy stretch at an appropriate speed, about 40 mph, leaned back against a strappeddown pack, as contented as the land I was gliding through. That’s one of the pleasures of traveling by bike: senses pricked awake by the wind, the noise and, yes, the vibration, you ride through the land, not just over it. You become participant, instead of spectator.

On U.S. 82 outside of Brookfield, I stopped for lunch at Jack Dempsey’s BBQ, something of a mecca for connoisseurs of Southern barbecue. Jack smoked his first piece of meat when he was nine. At 64, he was something of a cordon bleu among barbecue cooks. For years, I'd suffered through descriptions of his heavenly fare and dreamed of parking myself at one of his wooden booths. Turned out I was just in time; as I lapped up the better part of a pound of chopped pork, Jack announced that he was retiring.

“I want to go back in the country where I can live nice and quiet, go to church and Sunday school. That’s something I’ve never been able to do, working hundred-hour weeks here," he said. “If I’m ever going to just sit on the porch and rock, I'd better start thinking about it now, don’t you think ?"

“Can't argue,” I said. “But’re you just going to close down the pit for good?"

“Don't know, I’d kind of like to find, some good, worthy young person to sell the place to," Jack said. “But young people today, they just don't want to stay put, 'specially in the country. They get their driver’s license, take to driving, and they ain't worth a damn from then on."

Where I stayed that night, a hand-lettered sign informed me: “You have arrived in the best place you possibly could be the Deep South Motel."

A squall had blown in and the next morning was cold. The wind smelled of rain. About noon, the day made good its promise and the deluge began. I rolled into Hopeful about two o'clock.

By the time I rejoined U.S. 82 in Cuthbert, it was late afternoon. I hadn't eaten since the night before, so I stopped at the town square and asked the first person I saw where I could find some good food.

“Well, now, for home cookin’, there’s two places come to mind,” said Tom, a young black man dressed in work clothes. “I usually eat at the Grove if I'm hungry ’cause the service is quick. At the other place, you'll starve ’fore you get your food.”

I found the Grove Motel a short ways out of town. It was a small, squat travel court with a small dining room next to the office. A cryptic sign on the kitchen door said, “Keep Feet On The Floor.” In one corner, a soundless TV set flickered. “Man over at the square said I could get some home cookin' here," I said to the white-haired woman who sat at the cash register.

“We don’t know any other kind, honey," she said.

I didn't have time (o finish a cigarette before my order was served: fried chicken, boiled cabbage, candied yams, cornbread, iced tea. “Can I get you anything else, sugar?” the waitress asked. Tom was right. It was a safe bet that no one ever starved at the Grove.

Not far into Alabama, between Midway and Three Notch, the highway unreeled past a cinderblock roadhouse, Blueberry Hill, according to the Pepsi signs in the gravel parking lot. Inside, I was met by Bessie Mae Filg, the owner, a portly black woman with a mouthful of gold teeth. “Ooo-wee, am I sick. Must be from breathin' that bad air or somethin’,” she greeted me.

I bought a beer, not because I was thirsty but because Bessie Mae mentioned that she hadn’t sold anything that day. While I sipped it, we talked. I wanted to know why the Blueberry Hill had a long white line painted on its concrete floor. “When somebody gets all likkered up, we make 'em walk it tor fun,” she explained.

Then Bessie Mae quickly took care of the two obvious questions. Yes, Blueberry Hill was named after the Fats Domino song. “I got my thrill, on Blueberry Hill,” she sang. “Ooo-wee, I used to dance the night away when that came on the Rock-Ola.” And no, Fats Domino had never visited the roadhouse, although Bessie Mae hadn't given up hope. “Maybe, someday, he come to the Blueberry. '

Although it.was dusk and still drizzling, I left the highway and veered onto the unmarked side roads. One small settlement, nothing more than a dozen houses and an intersection with four stop signs, was named Smut Eye. A little ways up the road, I stopped at Dayvolt’s Country Store and asked about it. “Somebody had his nose where it shouldn't've been.” said an old boy named Tom Finn, scooting his chair closer to the wood-burning stove. “Got a smut eye. Name stuck."

“Really?” I said.

“Nope. Made it up,” said Tom. “But sounds good, don't it?”

In Birmingham, I stayed with Dave and Linda Precht, friends I hadn’t seen for five or six years.

After I unloaded the Harley and spread some of the rain-soaked gear out to dry, Dave and I drove around the woods outside of town. First, though, we stopped to pick up some beer and boiled green peanuts at Cherry’s Produce, an open-air fruit and bait stand. We visited the tiny antebellum town of Lowndesboro, which somehow had escaped the ravages of the Civil War. A handful of grand plantation homes and cramped slave quarters remained, a window into the South of another age, magnificent yet at the same time horrible.

Still in the mood for home cooking, I insisted on eating dinner at a soul food cafe that had been recommended to me a couple of days earlier. Dave had never heard of the Colonial Grill, so I called for directions. “We not far from the jailhouse,” the voice on the other end said. “You go past it ’till you see a whole lot of po-leece cars. Grill’s right across from there. We be the ones not wearin’ uniforms.”

“So where is it?” asked Dave when I got back from the phone.

“Uh, you know where the jail is?” I said.

The police cars were a big help, and we found the Colonial without problem. The cafe was dark, the rhythm ‘n’ blues loud. Every 10 seconds or so, the strobe of a surveillance camera flashed, blinding the customers and recording them for prosterity. I did my best not to look suspicious. Dave and I were the only ones who ate. The other patrons, a dozen or so black men, huddled around tables, nursing beers, smoking cigarettes down to the filters and talking of hard times and jobs that hadn’t panned out.

It was still raining when I started out the next day. I hadn’t gone far when I felt the need for a cup of coffee and a Marlboro; rain does that to me. At Granny Ruth’s Cafe in Eclectic, I had both. There was just one waitress, an old woman, her snowy hair pulled back in a severe bun. Again, I didn’t risk asking. But I did ask about the town’s name.

She knitted her brow and thought. “Eclectic,” she said, turning to the man in the booth behind me. “Don’t that mean perfect?”

“Means the best,” he replied.

The old waitress turned back to me. “The best,” she said. “That’s something to be proud of, ain’t it?”

I stopped again at Lake Kawaliga, which inspired Hank Williams to write his song about the wooden Indian. On one bank of the lake, there was a lifesized statue of Williams’ ficticious Kawaliga. It was made of concrete and steel. “They used to have a wooden Indian,” said Arthur Walter, a young man who tends bar at a lakeside restaurant. “But it was always getting stolen.” West of Birmingham, Alabama was open and hilly, the two-lane highway lined with timber-cleared fields that awaited spring planting. Red dirt roads feinted away from the pavement, beating a muddy path toward the distant timberline. Blossoming redbuds and dogwoods splotched the gray day with spatters of red and pink and white. For a long stretch, I had the road to myself. The Harley zipped along at about 60 mph. At that speed, there was no jolting, jarring or shuddering, only a pleasant quiver of the handlebars and footpegs.

But then I came upon a long line of dirt trucks, plowing down the road at 30 miles per and drenching me with splashes of red muck. When I finally passed the leader of the pack after 20 miles, I grabbed a couple of handfuls of throttle, eager to make up for lost time.

“Urn, no sir, I don’t know exactly how fast I was going,” I found myself saying a few minutes later. The Alabama state trooper in question was about to write me up for speeding and reckless driving. I could tell that he was very pleased. He had nailed a Californian, a motorcyclist to boot, riding a bike with a damn-Yankee plate. The situation called for quick thinking.

“Yessir. Ah’m livin’ in Californyuh now,” I said, drawling even more than usual. Chilled molasses couldn’t have dripped slower than the words from my mouth. “But ah was born and raised in the South. And it shore is mighty good to be back in the promised land.”

It worked. After I agreed with him that California was not fit for human habitation, even by Yankees, the trooper dropped the reckless driving charge. I had to surrender my driver’s license and promise to mail in my fine. “That’ll be listed here,” the trooper said, giving me a schedule of fines. Speeding, up to 80 mph, was $47.50. Driving on the wrong side of the road was $52.50. Running a red light was $37.50. Littering was $127.50. In Alabama, they took clean highways seriously.

The Harley needed gas and I needed to wring myself out, so I pulled into Bob & Bonnie’s Cafe & Grocery at the crossroads of U.S. 80 and Highway 5. I tended to the bike and then sat down at the cafe’s counter for a cup of hot coffee and a slice of rich, smoky pecan pie. Bonnie Henson was talking about her husband’s habit of adopting stray snakes.

“Once, Bob found a snake under a woodpile and put it in the glovebox of his truck. He was going to release it in the woods later. Next day, he opened the glove box and the snake had laid eggs all in there. We put the eggs on something out in the sun to see if they’d hatch. We watched, but they dried up,” Bonnie said.

“Another time, he had a snake in a box over in the store. It got out. Every morning, there’d be all this stuff knocked down from the bottom shelves. One morning, we opened the door and there it was. Been loose in there two weeks. Bob took it a long ways away and let it go.”

I started a debate when I asked how far it was to Jackson, Mississippi. Bonnie said 175 miles. A man at a table disagreed; after thoughtfully shoving a plug of chewing tobacco in his cheek, he guessed on the high side of 225 miles. The other customers came down in between. The issue finally was settled by a snuff-dipping high school boy, who suddenly bolted up and hot-footed it into the men’s bathroom. In an instant, he was back. “One-seventy-five,” he said with certainty. “Exactly.”

“How the hell...” I started, turning to Bonnie.

She looked as surprised as I felt. Then, Bonnie gave a throaty laugh. “I was amazed, myself, ’til I remembered,” she said. “There’s a map in there.”

Bonnie followed me outside and watched as I climbed on the Harley. “You hurry back, y’hear?” she called. “I’ll make sure Bob has the snakes put up.”

U.S. 80 crossed into Mississippi and I set out again on the back roads. Somewhere south of Meridian, I wandered into a tent revival. “Praise the Lord,” the elderly black preacher instructed his enthusiastic congregration, “that he may trickle down the economics.” About sundown, realizing that I was lost, I stopped at Booker’s Antique Shop for directions.

“Why not Mississippi,” said Johnny Booker, when I asked where I was.

“Huh?”

“That’s the name of this place: Whynot. When it was settled, people couldn’t agree on a name. They said ‘Why not this,’ ‘Why not that,”’ Johnny said. “They finally gave up and called it Whynot.”

The store was dark, musty, cluttered, a hodgepodge of old furniture, rusty farm tools, pottery and bric-a-brac. Near the front door, an overfed cat slumbered next to a roaring fire that licked out of a huge cast-iron stove. One room housed the remains of a country store, shelves and cases stocked with dusty cans, dry goods, household medicines, shoes, clothes.

Johnny wrung his hands as I poked around. He seemed to be about 40. He was nervous and tentative and sad, in the manner of people who spend a lot of time alone. I could tell he was glad to have company.

“Don’t get many visitors here since I closed the general store down,” Johnny said. “The store was Mama’s. When she died, I didn’t have the heart to keep it going. There’s just me now. I haven’t ordered anything, not since Mama died. I’m trying to sell the store out.”

I bought a couple of stale Moon Pies to help deplete the stock, suited up and walked to the porch. Johnny followed me.

“Real shame you couldn’t stay and visit for a while. Next time you’re passing through, drop in,” he said. It was more of a plea than a request.

“You know, since Mama’s gone, it’s only me and the old things,” Johnny said. Then the door closed, and shut him in with his memories.

Mississippi wore the morning like a smile. The rain had stopped during the night, and now the land unfolded beneath a blue sky. The horizon seemed a lifetime away. Clumps of wildflowers spackled the rolling fields that lined the highway, as the tarmac jogged past small truck farms. Men jostled along on John Deeres and International Harvesters; women tugged at the weeds in tiny flower gardens. Old people sat on porches and rocked like clock pendulums, looking into the present, but seeing only the past. Laundry fluffed and flapped in a clean breeze.

A narrow, pockmarked side road led to Kokomo. Or, rather, to what was left. An abandoned general store with a realtor’s sign out front. A cemetery. A railroad bed, but no track. “Wasn’t always this way,” said Maxine Jarrell, the town’s postmistress, when I asked about Kokomo. “Used to be a booming place. But no more. The ghosts are moving in.”

Maxine and her husband, Bill, were living in small quarters attached to the closet-sized post office. It was as if they imagined that their presence would keep the ghosts that had claimed the rest of the Kokomo from taking that, too.

“Used to be something,” said Bill. “Town started up in the ’teens when Fernwood Lumber came in with a turpentine distillery. People streamed in ’cause of the work. They put in tracks, a railroad roundhouse, a depot. Trains were arriving all the time. After 20 years, though, all the pine was gone, cut down. The company moved down the road. That was the beginning of the end. People started moving away. The railroad took up the tracks. Then last year, they sold the depot. Someone paid $150 for it and hauled it away. The post office here’s the only thing left of the old days. ’Cept for old Julius. Must be 87 or so now. He was one of the first ones here.”

“I got a call today,” said Maxine, sadly. “Julius died this morning. His time was finally up.”

“And that’s the story of Kokomo,” said Bill. “NO FIGHTING PERIOD,” read the notice on the wall at the Yellow Hill Cafe in Liberty. That was okay with me; I wanted fried catfish, not a sparring match. The Yellow Hill, favored by the town’s blacks, was unmarked but there was no mistaking it. Jukebox funk shoved out of the open front door. A dozen men clotted near the street, sipping out of hidden bottles. Inside, waitresses served up beers that had been iced down in metal washtubs. A jealous wife skirmished with her husband’s girlfriend, while the man in question swayed to the sassy beat with a third woman. The catfish was damn good.

It was outside the Yellow Hill that I met Leon Weatherspoon. Leon called himself Sly. He was small, fidgety, toothpick-thin, with chipped gold teeth and a wisp of a beard. Leon had just been front page news in four counties.

Seemed that Leon had argued with a police officer at a gambling joint. Leon went outside, got his .22caliber single-shot rifle, and called the cop out. The cop came, with a .357-magnum revolver. Leon fired. He missed. The cop fired. He missed. As Leon was reloading, the cop walked up, stuck the pistol to his chest and pulled the trigger four times. The rounds didn’t fire. Leon had the cop pinned when reinforcements arrived. Leon was arrested. The cop admitted to running the illegal gambling joint. Because of the unusual circumstances, Leon was released after paying a $57 fine for simple assault.

“Whoo-eee,” said Leon, after recounting the story. He took a swig from a pocket-sized bottle. “Things sure is complicated being a black man around here.”

From Liberty, I dropped down into Louisiana and crossed the Mississippi River on the St. Francisville ferry. Then I rode south, shadowing the river. The highway snaked back and forth, scrimmaging with the shored up riverbank, scooting me past oil rigs, pipe farms, refineries and huge storage tanks that squatted like mutant mushrooms. In the darkness, I skirted Baton Rouge and found a room for the night outside Donaldsonville.

I wasn’t far from the shrine of Our Lady of the Butane Tank, so I stopped the next morning and paid my respects. Our Lady is only one of dozens of folk shrines throughout Cajun Louisiana; this one watches over the fuel supply of a tiny house next door. Aiming west and north, I followed the back roads as they skirted the bayous and mounted the swamps. A thick fog lay across the land like heavy flannel, broken only by the ghostly forms of dead, rotting trees. The Harley bored a tunnel through the grayness, its exhaust rumble somehow strangled by the silence.

The last patches of fog finally evaporated near Gueydan. I stopped for a cup of coffee to celebrate. A couple of years ago, the mayor and the police chief here held a shootout on the main street. They’d had a long-standing feud. When the cashier gave me my change, she said, “You’d like Gueydan. It’s nice and quiet.”

North of the coastal swamps, the Louisiana prairie was scrubby and spartan and unhospitable. About the only thing it’s good for, is flooding. So that’s what the people do. Then they raise rice and grow catfish on it. As befitted the nature of the land, most of the towns were small and scrubby and spartan. The roads shot through them without pause. On the shoulders, chickens flapped madly, trying to get to the other side, and stray dogs sniffed, intent on dog business.

It was near one of the towns that Highway 14 abruptly disappeared in a red sea of Herefords. For the better part of a half-hour, two bent old men blocked the road as they escorted a couple of hundred head of cattle from one scruffy pasture to another. As they rode herd, the old men tugged at their overalls and spat great streams of tobacco juice.

“Why we move ’em?” repeated one, as I stood a judicious distance away. “Give us somethin' to do. Coupla days, we move ’em back.”

After a couple of ill-chosen turns, I decided that I was lost again. “Lookin' for Jennings,” I announced to a wizened farmer. He was stopped on a vacant length of gravel farm-to-market road, stooped over the grimy entrails of what looked to have been a ’55 GMC pickup. It was impossible to tell from the random parts strewn at his feet whether he was dismantling the truck or putting it back together. Either, I suspected, would have the same effect on how well it ran.

“Wellsir, you just head thataway,” he said, gesturing with a Mighty Joe Young of a monkey wrench. He was flailing away at the engine bay as I rode away.

In Jennings, I stopped and bought a couple of pounds of boudin at Ellis Cormier’s place. Boudin is a wonderfully spicy Cajun sausage made from rice, pork, pork liver and a lot of cayenne pepper. Ellis, a short, round, jolly man, is known around these parts as the Boudin King. In a good week, he sells 4000 pounds of boudin. “Eat a pound, have a soft drink, and you have a whole meal,” Ellis told me. “I could eat it three times a day.”

“Could?” I asked.

“Fm on a diet,” he sighed. “Not eatin’ much of anything anymore.”

The journey ended on a Saturday morning in Mamou. Two fiddles, a guitar, a squeezebox and a triangle were already making sweet chanky-chank when I pushed through the door of Fred Tete’s lounge. This was the weekly live radio broadcast of the Mamou Cajun Hour. Although it was still shy of 10 a.m., the lounge was dense with people. They drank and groped and sweated and danced, laughed in the humidity, driven by the old music that four stooped, slow-moving old men were playing.

“Laissez le bon temps rouler,” they shouted between songs. Let the good times roll.

Later, as he packed his fiddle, I asked Sadie Courville what it was about his music that made people so happy.

“Memories,” Sadie said. “They listen and they hear memories.”

Almost midnight, 1500 melancholy miles later, still three hours from the California state line, I sat in a truckstop trying to chain-drink enough coffee to fuel me back to my apartment. I was trying to make some sense of where I’d been.

Pouring another cup, the waitress looked at me closely. “What’s the matter, son?” she asked. “You look like you’re running away from home.”

I shot a glance out the window, at the road-grimy Harley. All of a sudden, it came to me. I felt contented.

“No ma'am,” I said. “I’m not running away from home. This time, I’m taking it with me.”

Butch had been wrong. Home wasn’t where the heart was. The heart, that’s where home was. All I had to do, was listen to the memories.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

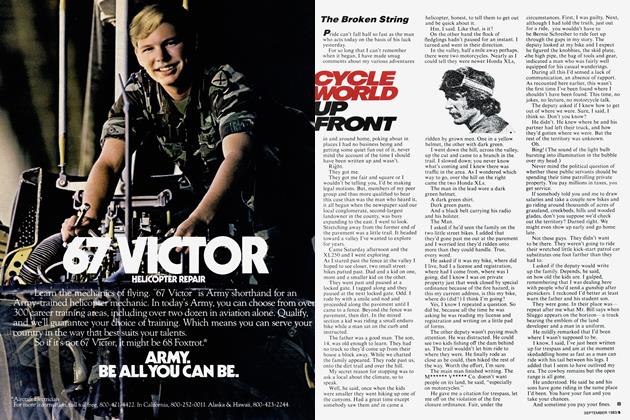

Up Front

Up FrontThe Broken String

September 1983 -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

September 1983 -

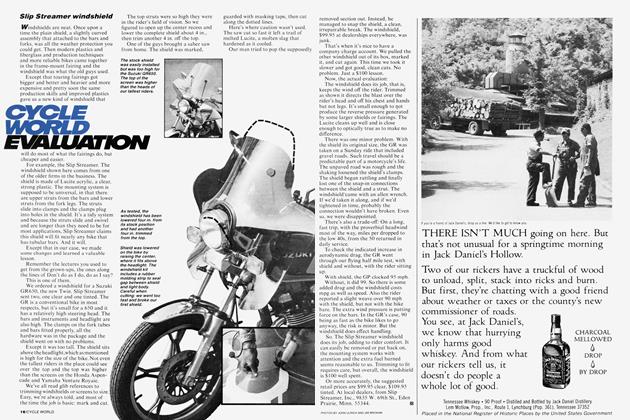

Cycle World Evaluation

Cycle World EvaluationSlip Streamer Windshield

September 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Book Reviews

September 1983 By John Ulrich -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

September 1983 -

Features

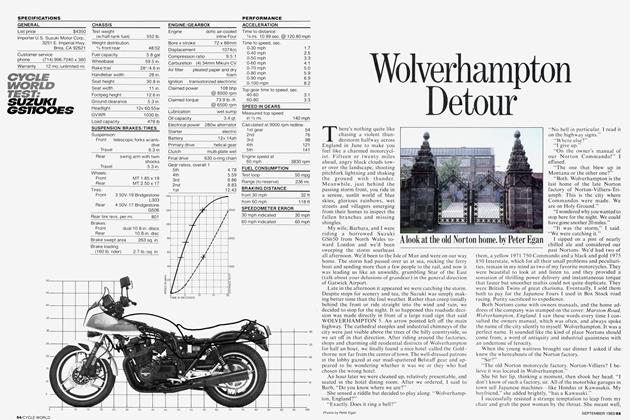

FeaturesWolverhampton Detour

September 1983