Wolverhampton Detour

There’s nothing quite like chasing a violent thunderstorm halfway across England in June to make you feel like a charmed motorcyclist. Fifteen or twenty miles ahead, angry black clouds tower over the landscape, shooting pitchfork lightning and shaking the ground with thunder.

Meanwhile, just behind the passing storm front, you ride in a serene, sunlit world of blue skies, glorious rainbows, wet streets and villagers emerging from their homes to inspect the fallen branches and missing shingles.

My wife, Barbara, and I were riding a borrowed Suzuki GS650 from North Wales toward London and we’d been sweeping the storm southeast all afternoon. We’d been to the Isle of Man and were on our way home. The storm had passed over us at sea, rocking the ferry boat and sending more than a few people to the rail, and now it was leading us like an unwieldy, grumbling Star of the East (talk about your delusions of grandeur) in the general direction of Gatwick Airport.

Late in the afternoon it appeared we were catching the storm. Despite stops for scenery and tea, the Suzuki was simply making better time than the foul weather. Rather than creep timidly behind the front or ride straight into the wind and rain, we decided to stop for the night. It so happened this roadside decision was made directly in front of a large road sign that said WOLVERHAMPTON 5. An arrow pointed left off the main highway. The cathedral steeples and industrial chimneys of the city were just visible above the trees of the hilly countryside, so we set off in that direction. After riding around the factories, shops and charming old residential districts of Wolverhampton for half an hour, we finally found a nice hotel called the Goldthorne not far from the center of town. The well-dressed patrons in the lobby gazed at our mud-spattered Belstaff gear and appeared to be wondering whether it was we or they who had chosen the wrong hotel.

An hour later we were cleaned up, relatively presentable, and seated in the hotel dining room. After we ordered, I said to Barb, “Do you know where we are?”

She sensed a riddle but decided to play along. “Wolverhampton, England?”

“Exactly. Does it ring a bell?”

“No bell in particular. I read it on the highway signs.”

“Where else?”

“I give up.”

“On the owner's manual of our Norton Commando!” I effused.

“The one that blew up in Montana or the other one?” “Both. Wolverhampton is the last home of the late Norton factory of Norton-Villiers-Triumph. This is the city where Commandos were made. We are on Holy Ground.”

“I wondered why you wanted to stop here for the night. We could have gone another 20 miles.”

“It was the storm,” I said. “We were catching it.”

I sipped on a pint of nearly chilled ale and considered our past Nortons. We’d had two of them, a yellow 1971 750 Commando and a black and gold 1975 850 Interstate, which for all their small problems and peculiarities, remain in my mind as two of my favorite motorcycles. They were beautiful to look at and listen to, and they provided a sensation of thrilling power delivery and instantaneous torque that faster but smoother multis could not quite duplicate. They were British Twins of great charisma. Eventually, I sold them both to pay for the Japanese Fours I used in Box Stock road racing. Purity sacrificed to expedience.

Both Nortons came with owners manuals, and the home address of the company was stamped on the cover: Marston Road, Wolverhampton, England. I saw these words every time I consulted the owners manual, which was often, and always spoke the name of the city silently to myself. Wolverhampton. It was a perfect name. It sounded like the kind of place Nortons should come from; a word of antiquity and industrial quaintness with an undertone of ferocity.

When the young waitress brought our dinner I asked if she knew the whereabouts of the Norton factory.

“Sir?”

“The old Norton motorcycle factory. Norton-Villiers? I believe it was located in Wolverhampton.”

She bit her lip, thinking a moment, then shook her head. “I don't know of such a factory, sir. All of the motorbike garages in town sell Japanese machines—like Hondas or Kawasakis. My boyfriend,” she added brightly, “has a Kawasaki.”

I successfully resisted a strange temptation to leap from my chair and grab the poor woman by the throat. She meant well, but how could anyone live in Wolverhampton unaware of the fate or existence of the Norton company. She was like a Dubliner who didn’t know if James Joyce was dead or alive. Disgraceful.

In my mind’s eye, these many years, I had imagined Wolverhampton as a city whose very existence hinged on the success or failure of Norton motorcycles; a place where framed paintings of James Lansdowne Norton and speeding Commandos hung above the glittering rows of bottles in every pub, and workingmen toasted their memory; a town where mothers and children included Geoff Duke, Peter Williams and Bob Trigg in their bedtime prayers. Never mind that the factory had moved from Birmingham to Woolwich before landing here in 1969, amid the ceaseless turmoil of British corporate division and amalgamation, or that much of the final assembly was done at Woolwich. I had nevertheless expected to find Wolverhampton a solid Norton town, still mourning its loss. Instead I’d discovered a large, busy industrial city that could swallow a motorcycle factory whole without blinking, and a waitress who didn’t know Nortons from Maytags.

I cleared my throat. “So you don’t know of the Norton factory?”

“No sir.”

A middle-aged waitress who was clearing the next table overheard our conversation and stopped in her tracks. She stared at the younger woman quizzically for a moment, then turned to us. “The Norton factory,” she said quietly, “is across the street.” She pointed out the restaurant window. “That wall is the back of the Norton works. The main gate is just around the corner, on Marston Road. The factory occupies most of that block. It’s been closed now for over five years.”

The woman left us staring out the window at a high red brick wall with wrought iron trim. “Amazing,” I said. “Across the street. Looks like we picked the right hotel.” It was nearly dark, so we put off exploration until the next day.

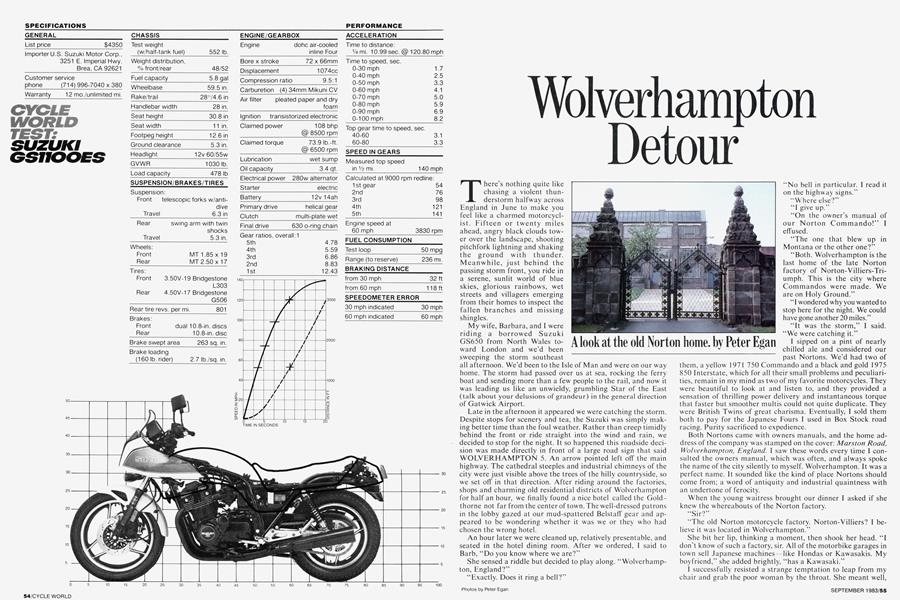

It was a sunny morning with Sunday church bells ringing when we stepped out of the hotel after breakfast. The streets were quiet and nearly empty, except for random couples and families out for morning walks in their church-going finery. We crossed the street and strolled up Marston Road, following the brick wall until we came to a pair of elaborate iron gates with the name Villiers fashoned in wrought iron. The gates were locked, but we could see an office building flanked by long brick assembly line structures with skylights and multi-pane windows. A large green lawn with a circular drive extended from the office building to the gates. The factory had a civilized, friendly look about it, as though it might have been the entrance to an old prep school or university.

We walked farther up the street, almost to the corner of the factory where Marston Road intersected with Villiers Street, and found an open gate. Beside the gate was a small time clock shed with many broken windows and the door swinging idly on its hinges. Inside, the floor was scattered with old Norton record books, technical bulletins, old teacups and magazines and industrial safety posters (Protect Your Eyes!, Safety is Everybody’s Business, etc.). A huge key closet was open, with keys marked Storeroom #4, Milling Tool Room, Paintshop Main Door, and so on, hanging on cup hooks. Rain had blown in the broken windows and dampened the record books scattered on the floor.

I picked up a large volume entitled Detail Occurence Book and began reading. Some typical entries, from October of 1974, written with a black ink pen in a florid hand: “2 engines running experimental tonight” and “Radiator in piston shop requires attention; leaking badly” and “All toilets in D Shop under canteen blocked except one” followed by “two engines still running experimental after weekend.” They had more nerve than I’d ever had, leaving their Norton engines running all weekend.

We walked outside and wandered around the factory buildings, most of which were gutted and empty. One, however, had all its windows intact and was filled with machine tools and parts bins. We walked around the corner and found a construction crew sitting against the building, taking a tea and cigarette break. They explained that several of the factory buildings had been leased to small industrial companies. Lawnmower engines being produced in this particular building, they said. Several more buildings would soon be fixed up, and these men were part of the renovation crew hired to put them in order. The wiring, they said, was a mess.

As we walked back toward the gate, a dump truck rumbled in and backed up to another of the buildings. Several workmen jumped out and began shoveling a pile of debris from a loading dock into the open truck. The old factory was getting to be a lively place on a Sunday morning.

We passed the time clock shed and started out the gate, but I turned around and went back into the shed. I came out carrying a water-soaked Detail Occurrence Book. Usually I’m not much on looting and souvenir hunting, but I thought at least one momento should be saved from the scoop shovel and the dump truck. We went back to the hotel and I stuffed the book into the Suzuki’s tank bag. I later dried its pages back into wrinkled parchment on a hotel radiator in London, lightening our luggage by about five pounds.

We checked out of the hotel, climbed on the Suzuki and slowly circled the block. Adjacent to the Norton-Villiers plant were other buildings representing the great industrial names of England: Fafner, Spicer and Lucas, as well as several metal plating and aluminum casting companies. The Norton people didn’t have to walk far for their bearings, electrics and other specialized components. We completed our circle of the block and found that a large plywood realty sign had been nailed over the Norton-Villiers name at every corner of the factory.

I tried to ride away from the Norton

plant with a minimum of self-inflicted wistfulness and irony, but there was no denying that those peaceful brick buildings on that warm Sunday morning were inhabited by their share of ghosts. Just beyond vision and barely above the aural range of the human ear, the place was probably alive with the clamor of industrial production; it was possible to imagine cartloads of 750 Combat engines being hauled in gleaming rows from the assembly plant, or triangular timing gear covers with the lovely Norton emblem being buffed to a high luster in the metal finishing shop, or Peter Williams walking through the gates to look at his new Isle of Man ride.

Battlefields, historic racing circuits, famous movie locations and the homes of poets and artists surround themselves with a similar aura. They continue to ring with the presence of great endeavor long after the principal characters have left the scene. They become, if not sanctified, at least Certified Important Places on Earth. Nortons had been great motorcycles, in their own English way, and greatness does not desert a place just because bank managers and financiers decide the game is over. Nailing a realty sign over the Norton-Villiers could now have little effect on the place. The Norton name, peeking out from behind, was simply more powerful than the realtor’s.

(In fact, I worried for the health of the man who nailed it up there; risky business, like messing around with a pharoah’s tomb.)

I liked to imagine that it was just a matter of time until all this was put right. Sometime after the turn of the next century people would realize that the Norton factory was a part of the national heritage. They’d return with painters, carpenters and bricklayers and a large bundle of historical photographs and reconstruct everything just as it was in. 1975. The Norton works would take its place beside Ann Hathaway’s cottage and the Bronte homestead on the roster of historical landmarks. Tour guides in 1975 period costumes (bellbottoms, etc.) would say things like, “It was at this drawing board that Bob Trigg designed the Isolastic engine mounts,’’ or “This is where they put the gold pinstriping on the gas tanks.”

It would take a while for us to realize that our loveliest industrial designs were as great a contribution to Art as the poetry, painting and sculpture of the 20th Century. In the mean ime, the romance of an old British bike factory, like the call of motorcycling itself, was as selective in its appeal as a silent dog whistle. You had to have owned a Norton or have wanted to own one very badlyin order to hear it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Broken String

September 1983 -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

September 1983 -

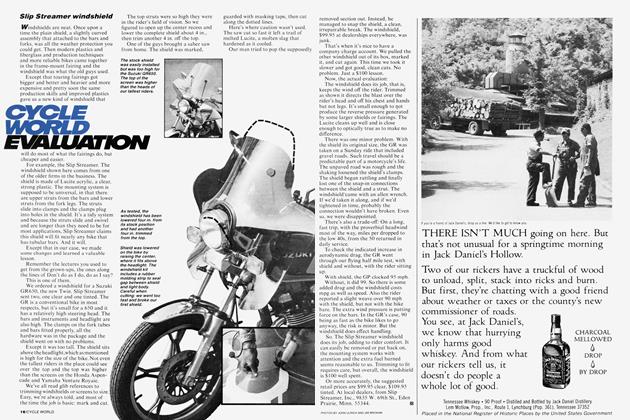

Cycle World Evaluation

Cycle World EvaluationSlip Streamer Windshield

September 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Book Reviews

September 1983 By John Ulrich -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

September 1983 -

Features

FeaturesHeartfelt Highways

September 1983 By Wade Roberts