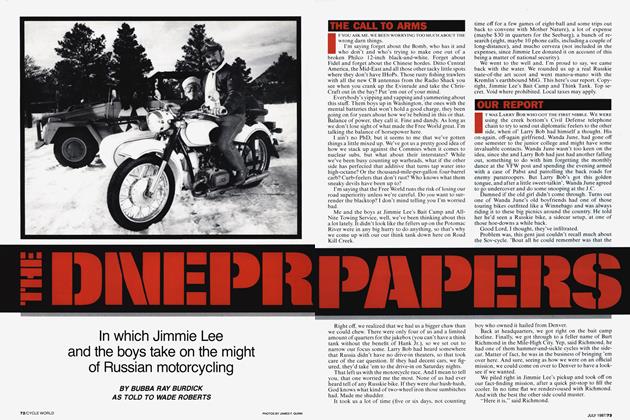

Breaking The Rules

FEATURES

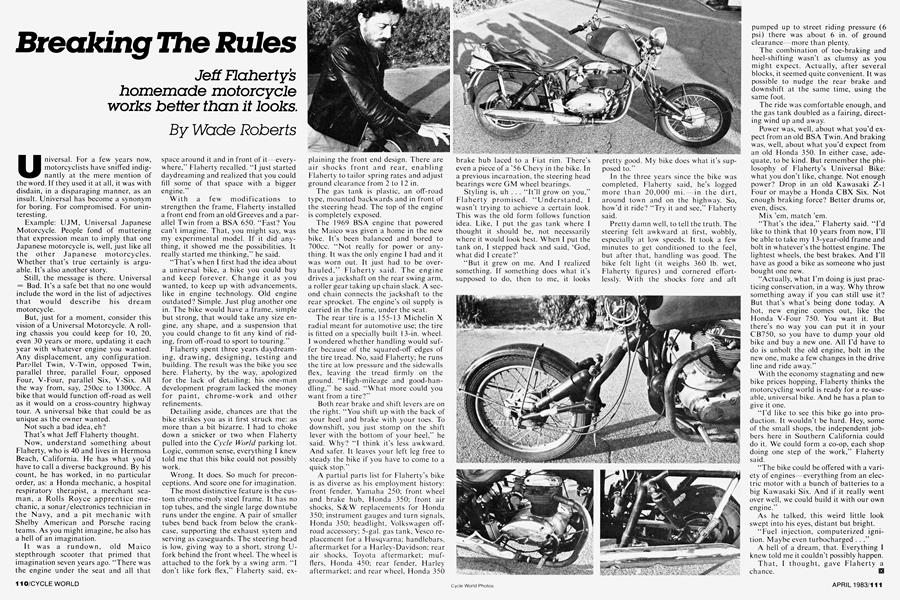

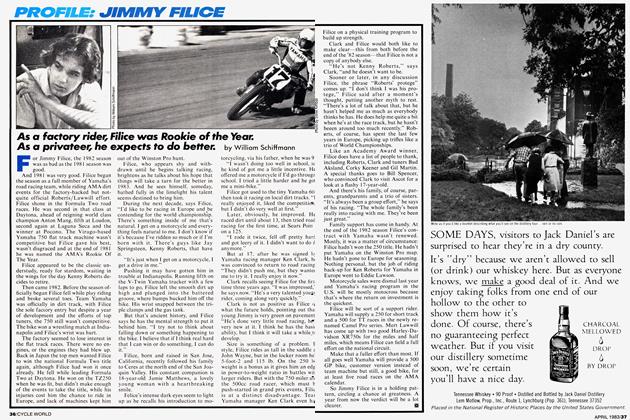

Jeff Flaherty’s homemade motorcycle works better than it looks.

Wade Roberts

Universal. For a few years now, motorcyclists have sniffed indignantly at the mere mention of the word. If they used it at all, it was with disdain, in a disparaging manner, as an insult. Universal has become a synonym for boring. For compromised. For uninteresting.

Example: UJM, Universal Japanese Motorcycle. People fond of muttering that expression mean to imply that one Japanese motorcycle is, well, just like all the other Japanese motorcycles. Whether that's true certainly is arguable. It’s also another story.

Still, the message is there. Universal = Bad. It’s a safe bet that no one would include the word in the list of adjectives that would describe his dream motorcycle.

But, just for a moment, consider this vision of a Universal Motorcycle. A rolling chassis you could keep for 10, 20, even 30 years or more, updating it each year with whatever engine you wanted. Any displacement, any configuration. Parallel Twin, V-Twin, opposed Twin, parallel three, parallel Four, opposed Four, V-Four, parallel Six, V-Six. All the way from, say, 250cc to 1 300cc. A bike that would function off-road as well as it would on a cross-country highway tour. A universal bike that could be as unique as the owner wanted.

Not such a bad idea, eh?

That’s what Jeff Flaherty thought. Now, understand something about Flaherty, who is 40 and lives in Hermosa Beach, California. He has what you’d have to call a diverse background. By his count, he has worked, in no particular order, as: a Honda mechanic, a hospital respiratory therapist, a merchant seaman, a Rolls Royce apprentice mechanic, a sonar/electronics technician in the Navy, and a pit mechanic with Shelby American and Porsche racing teams. As you might imagine, he also has a hell of an imagination.

It was a rundown, old Maico stepthrough scooter that primed that imagination seven years ago. “There was the engine under the seat and all that space around it and in front of it everywhere,” Flaherty recalled. “I just started daydreaming and realized that you could fill some of that space with a bigger engine.”

With a few modifications to strengthen the frame, Flaherty installed a front end from an old Greeves and a parallel Twin from a BSA 650. “Fast? You can’t imagine. That, you might say, was my experimental model. If it did anything, it showed me the possibilities. It really started me thinking,” he said.

“That’s when I first had the idea about a universal bike, a bike you could buy and keep forever. Change it as you wanted, to keep up with advancements, like in engine technology. Old engine outdated? Simple. Just plug another one in. The bike would have a frame, simple but strong, that would take any size engine, any shape, and a suspension that you could change to fit any kind of riding, from off-road to sport to touring.”

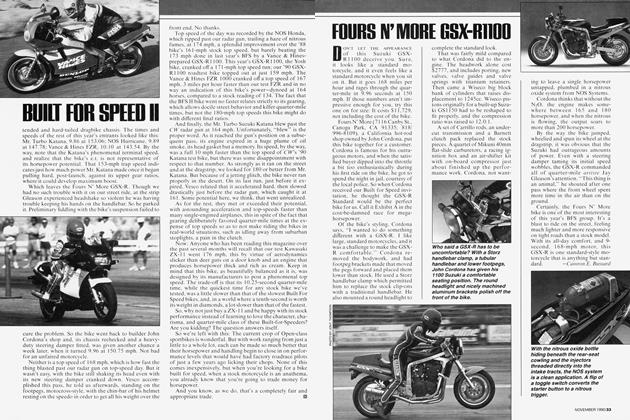

Flaherty spent three years daydreaming, drawing, designing, testing and building. The result was the bike you see here. Flaherty, by the way, apologized for the lack of detailing; his one-man development program lacked the money for paint, chrome-work and other refinements.

Detailing aside, chances are that the bike strikes you as it first struck me: as more than a bit bizarre. I had to choke down a snicker or two when Flaherty pulled into the Cycle World parking lot. Logic, common sense, everything I knew told me that this bike could not possibly work.

Wrong. It does. So much for preconceptions. And score one for imagination.

The most distinctive feature is the custom chrome-moly steel frame. It has no top tubes, and the single large downtube runs under the engine. A pair of smaller tubes bend back from below the crankcase, supporting the exhaust sytem and serving as caseguards. The steering head is low, giving way to a short, strong Ufork behind the front wheel. The wheel is attached to the fork by a swing arm. “I don't like fork flex,” Flaherty said, explaining the front end design. There are air shocks front and rear, enabling Flaherty to tailor spring rates and adjust ground clearance from 2 to 1 2 in.

The gas tank is plastic, an off-road type, mounted backwards and in front of the steering head. The top of the engine is completely exposed.

The 1969 BSA engine that powered the Maico was given a home in the new bike. It’s been balanced and bored to 700cc. “Not really for power or anything. It was the only engine I had and it was worn out. It just had to be overhauled,” Flaherty said. The engine drives a jackshaft on the rear swing arm, a roller gear taking up chain slack. A second chain connects the jackshaft to the rear sprocket. The engine’s oil supply is carried in the frame, under the seat.

The rear tire is a 155-13 Michelin X radial meant for automotive use; the tire is fitted on a specially built 13-in. wheel.

I wondered whether handling would suffer because of the squared-off edges of the tire tread. No, said Flaherty; he runs the tire at low pressure and the sidewalls flex, leaving the tread firmly on the ground. “High-mileage and good-handling,” he said. “What more could you want from a tire?”

Both rear brake and shift levers are on the right. “You shift up with the back of your heel and brake with your toes. To downshift, you just stomp on the shift lever with the bottom of your heel,” he said. Why? “I think it’s less awkward. And safer. It leaves your left leg free to steady the bike if you have to come to a quick stop.”

A partial parts list for Flaherty’s bike is as diverse as his employment history: front fender, Yamaha 250; front wheel and brake hub, Honda 350; front air shocks, S&W replacements for Honda 350; instrument gauges and turn signals, Honda 350; headlight, Volkswagen offroad accessory; 5-gal. gas tank, Vesco replacement for a Husqvarna; handlebars, aftermarket for a Harley-Davidson; rear air shocks, Toyota aftermarket; mufflers, Honda 450; rear fender, Harley aftermarket; and rear wheel, Honda 350 brake hub laced to a Fiat rim. There’s even a piece of a ’56 Chevy in the bike. In a previous incarnation, the steering head bearings were GM wheel bearings.

Styling is, uh . . . “It’ll grow on you,” Flaherty promised. “Understand, I wasn’t trying to achieve a certain look. This was the old form follows function idea. Like, I put the gas tank where I thought it should be, not necessarily where it would look best. When I put the tank on, I stepped back and said, ‘God, what did I create?’

“But it grew on me. And I realized something. If something does what it’s supposed to do, then to me, it looks In the three years since the bike was completed, Flaherty said, he’s logged more than 20,000 mi. in the dirt, around town and on the highway. So, how’d it ride? “Try it and see,” Flaherty said.

Pretty damn well, to tell the truth. The steering felt awkward at first, wobbly, especially at low speeds. It took a few minutes to get conditioned to the feel, but after that, handling was good. The bike felt light (it weighs 360 lb. wet, Flaherty figures) and cornered effortlessly. With the shocks fore and aft pumped up to street riding pressure (6 psi) there was about 6 in. of ground clearance more than plenty.

The combination of toe-braking and heel-shifting wasn’t as clumsy as you might expect. Actually, after several blocks, it seemed quite convenient. It was possible to nudge the rear brake and downshift at the same time, using the same foot.

The ride was comfortable enough, and the gas tank doubled as a fairing, directing wind up and away.

Power was, well, about what you’d expect from an old BSA Twin. And braking was, well, about what you’d expect from an old Honda 350. In either case, adequate, to be kind. But remember the philosophy of Flaherty’s Universal Bike: what you don't like, change. Not enough power? Drop in an old Kawasaki Z-l Four or maybe a Honda CBX Six. Not enough braking force? Better drums or, even, discs.

Mix ’em, match ’em.

“That’s the idea,” Flaherty said. “I’d like to think that 10 years from now, I’ll be able to take my 13-year-old frame and bolt in whatever’s the hottest engine. The lightest wheels, the best brakes. And I’ll have as good a bike as someone who just bought one new.

“Actually, what I’m doing is just practicing conservation, in a way. Why throw something away if you can still use it? But that’s what’s being done today. A hot, new engine comes out, like the Honda V-Four 750. You want it. But there’s no way you can put it in your CB750, so you have to dump your old bike and buy a new one. All I’d have to do is unbolt the old engine, bolt in the new one, make a few changes in the drive line and ride away.”

With the economy stagnating and new bike prices hopping, Flaherty thinks the motorcycling world is ready for a re-useable, universal bike. And he has a plan to give it one.

“I’d like to see this bike go into production. It wouldn’t be hard. Hey, some of the small shops, the independent jobbers here in Southern California could do it. We could form a co-op, each shop doing one step of the work,” Flaherty said.

“The bike could be offered with a variety of engines—everything from an electric motor with a bunch of batteries to a big Kawasaki Six. And if it really went over well, we could build it with our own engine.”

As he talked, this weird little look swept into his eyes, distant but bright.

“Fuel injection, computerized ignition. Maybe even turbocharged . .

A hell of a dream, that. Everything I knew told me it couldn’t possibly happen.

That, I thought, gave Flaherty a chance.