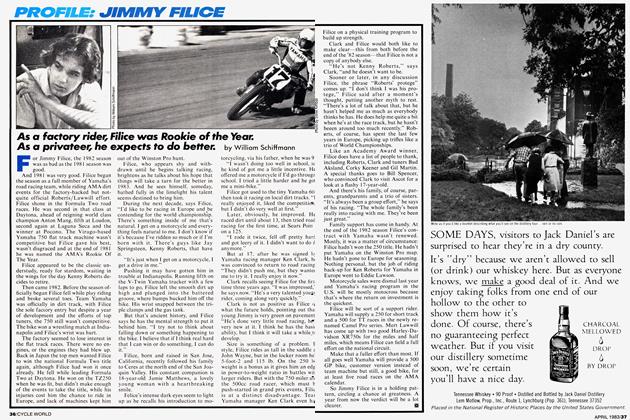

Project Ducati

Teaching an Old Duck New Tricks, as in Power! ...Speed! ...Performance!

John Ulrich

Big Twins have their appeal. There’s a comfort in their large, well-spaced power pulses, a de-

light in their exhaust cadence, a mystique in their ability to cruise quickly at low rpm.

Big Twins also have their limits. As sold for street use, Twins aren’t very quick, making less power and delivering less performance than smaller four-cylinder motorcycles.

The quickest and fastest stock Twin now available is the Harley-Davidson XR1000, which turns the quarter in 12.88 sec. at a terminal speed of 101.23 mph. The catch is that the XR1000 sells for about $7000.

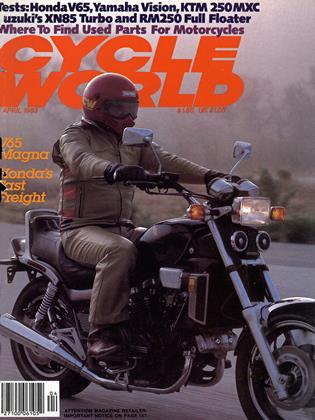

Which brings us to the 1975 Ducati GT860 I bought used for $1500. In stock condition, the bike was fun to ride, loud and slow—just as it was when new, judging by the 860 tested in the July 1975 issue of Cycle World. That 860 turned 13.49 sec. and 96.46 mph at the drag strip, and reached 109 mph in the half mile. For reference, the quickest and fastest Ducati tested by this magazine was a 900SD Darmah featured in the May 1978 issue, turning 12.98 and 101.23 mph in the quarter and reaching 11 1 mph in the half mile.

In last month’s issue, our experiments with a Seca 650 Four were a resounding success, resulting in dragstrip times of 12.18 sec. at 108.69 mph with stock exhaust and airbox, compared to the Seca’s as-new best of 12.78 sec. at 103.68 and the Seca’s post-5500-miles figures of 13.39 sec. at 98.90 mph.

All of which made us wonder if the Ducati could be similarly transformed, preferably without spending as much

money ($1116) as consumed by the Seca 650 project.

We started at the logical place displacement—with a $225 set of 87mm (stock bore is 86mm) forged street pistons from Bracken/Guest Racing, not exactly a well-known outfit. Kevin Bracken is an engineer by profession, commuting 80 mi. a day during the week on one of two Ducati street bikes, racing another Ducati on weekends. Bracken has won a couple of California club championships and was first in the Modified Production class in the AMA Battle Of The Twins (BOTT) race at Elkhart Lake in 1982. Tony Guest is a banker, former drag racer, club road racer, Ducati enthusiast and close friend to Bracken. The pair pooled their knowledge and resources to form Bracken/ Guest Racing, developing and selling a line of high-performance Ducati parts to help finance their racing.

Both receive help from Woods Motor Shop (525 W. Colorado St., Glendale, Calif. 91204, 213/956-0698), a Ducati/ Moto Guzzi/Laverda dealership specializing in high-performance modifications and run by Jim Woods. Woods retails the products developed by Bracken/ Guest Racing.

The street pistons we bought, derived from pistons developed in Bracken’s racebike, were tested in months of commuting in Bracken’s two street bikes. Bracken is quick to point out that much of the design work and testing evaluation for the racing and street pistons was done by C.R. Axtell, a noted tuner involved in the development of the XR750 HarleyDavidson.

Bracken says his most difficult task in developing the street piston was eliminating detonation when using readilyavailable pump gasoline. Changes in the piston dome radius finally solved the problem, allowing 10:1 c.r. (stock is 9:1) without detonation on either leaded or unleaded premium. Bracken used both types of fuel in his experiments over a two-year period, and encountered no valve seat problems when using unleaded.

Stock Ducati 860 pistons are forged in Italy by Borgo, weigh 352 grams each and yield 864cc. Bracken’s pistons are forged in the U.S. by TRW, weigh 350 grams and yield 884.6cc—we’ll call it 885cc.

Bracken’s pistons use standard Yamaha TT500 rings, including a threepiece oil control ring. The stock Ducati pistons have a one-piece oil scraper ring backed in the groove by a coil spring.

The pistons went with the Ducati cylinders to Vance & Hines Racing (14010 Marquardt, Santa Fe Springs, Calif. 90670, 213/921-7461) for cylinder boring. There, Ron Nelson did the boring and honed the bore to VHR’s characteristic 500-grit glossy finish. Byron Hines of VHR prefers a glossy cylinder finish to the more common, coarser 220 grit finish, saying that the finer finish improves ring seal and oil control, reduces ring wear, and provides a better bearing surface for the piston skirt. Hines says a coarser finish, examined under a microscope, reveals ridges and troughs in the cylinder wall, reducing the surface area contacted by a ring face and increasing the amount of oil and compression lost past the rings, as well as accelerating ring wear. (Hines admits that his finer finish increases ring break-in time required. Hines says coarser cylinder finishes were developed when piston rings were commonly out-of-round and irregular, and when substantial ring wear was required to produce an adequate seal.)

Boring and honing the two Ducati cylinders to match the pistons cost $52, and the cylinders were ready. I Vi weeks after they were delivered to VHR.

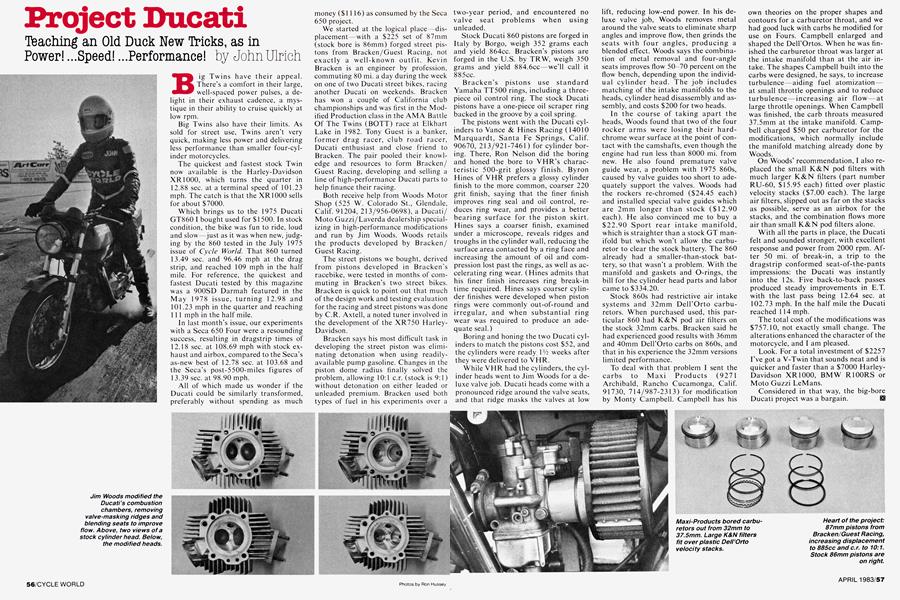

While VHR had the cylinders, the cylinder heads went to Jim Woods for a deluxe valve job. Ducati heads come with a pronounced ridge around the valve seats, and that ridge masks the valves at low lift, reducing low-end power. In his deluxe valve job, Woods removes metal around the valve seats to eliminate sharp angles and improve flow, then grinds the seats with four angles, producing a blended effect. Woods says the combination of metal removal and four-angle seats improves flow 50-70 percent on the flow bench, depending upon the individual cylinder head. The job includes matching of the intake manifolds to the heads, cylinder head disassembly and assembly, and costs $200 for two heads.

In the course of taking apart the heads, Woods found that two of the four rocker arms were losing their hardchrome wear surface at the point of contact with the camshafts, even though the engine had run less than 8000 mi. from new. He also found premature valve guide wear, a problem with 1975 860s, caused by valve guides too short to adequately support the valves. Woods had the rockers re-chromed ($24.45 each) and installed special valve guides which are 2mm longer than stock ($12.90 each). He also convinced me to buy a $22.90 Sport rear intake manifold, which is straighter than a stock GT manifold but which won’t allow the carburetor to clear the stock battery. The 860 already had a smaller-than-stock battery, so that wasn’t a problem. With the manifold and gaskets and O-rings, the bill for the cylinder head parts and labor came to $334.20.

Stock 860s had restrictive air intake systems and 32mm Dell’Orto carburetors. When purchased used, this particular 860 had K&N pod air filters on the stock 32mm carbs. Bracken said he had experienced good results with 36mm and 40mm Dell’Orto carbs on 860s, and that in his experience the 32mm versions limited performance.

To deal with that problem I sent the carbs to Maxi Products (9271 Archibald, Rancho Cucamonga, Calif. 91730, 714/987-2313) for modification by Monty Campbell. Campbell has his own theories on the proper shapes and contours for a carburetor throat, and we had good luck with carbs he modified for use on Fours. Campbell enlarged and shaped the Dell’Ortos. When he was finished the carburetor throat was larger at the intake manifold than at the air intake. The shapes Campbell built into the carbs were designed, he says, to increase turbulence—aiding fuel atomization— at small throttle openings and to reduce turbulence—increasing air flow—at large throttle openings. When Campbell was finished, the carb throats measured 37.5mm at the intake manifold. Campbell charged $50 per carburetor for the modifications, which normally include the manifold matching already done by Woods.

On Woods’ recommendation, I also replaced the small K&N pod filters with much larger K&N filters (part number RU-60, $15.95 each) fitted over plastic velocity stacks ($7.00 each). The large air filters, slipped out as far on the stacks as possible, serve as an airbox for the stacks, and the combination flows more air than small K&N pod filters alone.

With all the parts in place, the Ducati felt and sounded stronger, with excellent response and power from 2000 rpm. After 50 mi. of break-in, a trip to the dragstrip conformed seat-of-the-pants impressions: the Ducati was instantly into the 12s. Five back-to-back passes produced steady improvements in E.T. with the last pass being 12.64 sec. at 102.73 mph. In the half mile the Ducati reached 1 14 mph.

The total cost of the modifications was $757.10, not exactly small change. The alterations enhanced the character of the motorcycle, and I am pleased.

Look. For a total investment of $2257 I’ve got a V-Twin that sounds neat and is quicker and faster than a $7000 HarleyDavidson XR1000, BMW R100RS or Moto Guzzi LeMans.

Considered in that way, the big-bore Ducati project was a bargain. E8