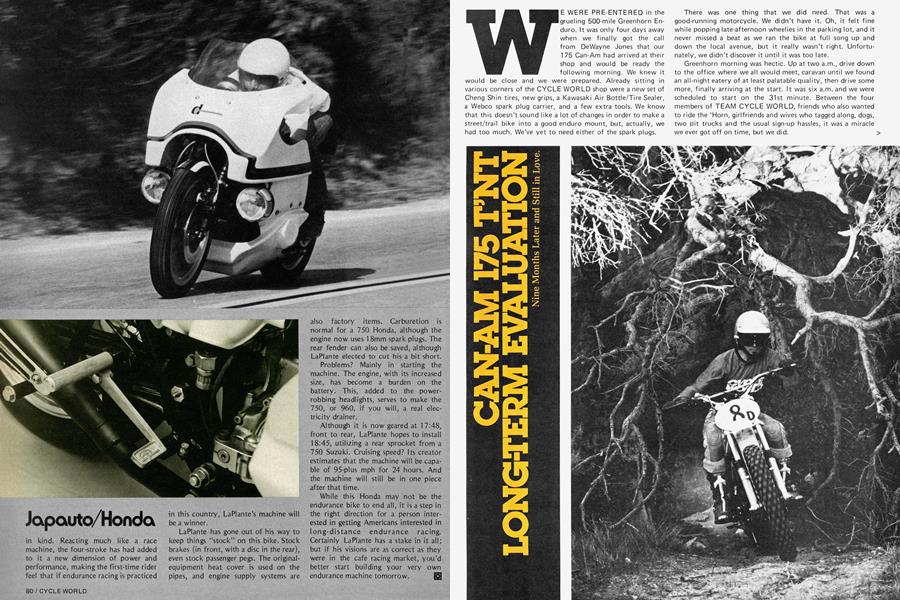

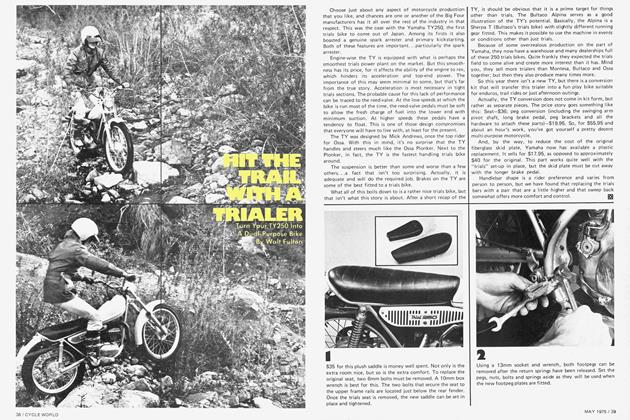

CAN-AM 175 TNT LONG-TERM EVALUATION

Nine Months Later and Still in Love.

WE WERE PRE-ENTERED in the grueling 500-mile Greenhorn Enduro. It was only four days away when we finally got the call from DeWayne Jones that our 175 Can-Am had arrived at their shop and would be ready the following morning. We knew it would be close and we were prepared. Already sitting in various corners of the CYCLE WORLD shop were a new set of Cheng Shin tires, new grips, a Kawasaki Air Bottle/Tire Sealer, a Webco spark plug carrier, and a few extra tools. We know that this doesn't sound like a lot of changes in order to make a street/trail bike into a good enduro mount, but, actually, we had too much. We've yet to need either of the spark plugs.

There was one thing that we did need. That was a good-running motorcycle. We didn't have it. Oh, it felt fine while popping late-afternoon wheelies in the parking lot, and it never missed a beat as we ran the bike at full song up and down the local avenue, but it really wasn't right. Unfortu nately, we didn't discover it until it was too late.

Greenhorn morning was hectic. Up at two a.m., drive down to the office where we all would meet, caravan until we found an all-night eatery of at least palatable quality, then drive some more, finally arriving at the start. It was six a.m. and we were scheduled to start on the 31st minute. Between the four members of TEAM CYCLE WORLD, friends who also wanted to ride the `Horn, girlfriends and wives who tagged along, dogs, two pit trucks and the usual sign-up hassles, it was a miracle we ever got off on time, but we did.

First a little tour through the foothill streets of Pasadena, where we managed to get lost twice in two miles, then up into the hills. Five miles out, problems.

The Can-Am started running rich. At first it began as a slight blubbering on the top end, but very slowly, as the miles piled on, it began getting worse. Anger seems to be instinctive when something goes wrong with your bike and we were mad, but we kept trying to figure out what it was as we rode along. Maybe we overdid it when it was new and scored the piston a little. Or maybe the rings were seating in and, with blow-by diminishing, the mixture was burning richer. Whatever it was, the bike was still running, so we weren't going to screw around with it until it got really serious. Besides, it just might clear itself up.

After one gas stop, we hit the first check some 83 miles out. Perfect. We zeroed it. But the Can-Am had been getting progressively worse. We stopped to change the jetting. The Bing carburetor is pretty easy to change jets on, but you have to really be careful as you work around a hot engine. Five jetting changes later, still no improvement. We put the stock jet back in and fired up the bike. First kick, just like always, it fired. As we pulled away from that first check, the bike and rider were 57 minutes behind schedule. But the schedule was an easy one on this part of the 'Horn and the next check was more than 60 miles away.

By now, the Can-Am could only be run at one-quarter throttle. The engine would eventually get up to maximum revs in each gear, though acceleration lacked its usual briskness.

Opening the throttle any more than one-quarter would start the engine blubbering. Eighty mph indicated was finally coaxed out of the 175 as it and the rider flew through a small mountain town, elevation 8000 ft. The sign said Speed Limit: 35 mph, but the local gendarme was not to be seen, and no one complained. Rider after rider was passed on the highway before the course markings indicated a dirt trail to be followed.

Riding the faltering bike on the trail was a chore. The concentration needed to maintain the exact throttle opening while bounding over the terrain—upshifting, downshifting, cornering and braking—was tiring. But, by the second check, 47 of those late minutes had been made up.

Later on the first day, the schedules tightened up, and the machine could no longer be coaxed into performing well. Just a little more than 210 miles from the start, way behind schedule, the rider and machine retired. There's no doubt that they could have finished the first day, but it would have been futile since they would have been eliminated for being over an hour late at the final check. Still, the engine would run.

After the 'Horn, we discovered what the problem with the engine was. One of the engine seals was defective. All day long it had been seeping transmission oil into the lower end. The incredible thing was, that the engine didn't seize or even show signs of impending seizure. It was running in the area of 9000 rpm for 10 minutes straight at times and it showed no signs of sticking. Not only would the small throttle opening cause it to run lean, but the mixing of Torco two-stroke oil and gear lube from the transmission would certainly have caused problems. But the engine proved itself nearly bulletproof. And it continues to prove it every time we race it.

Once the problem had been corrected (under warranty), the bike ran like a champ. The spark plug has been removed several times for cleaning, but to this day, it is still running on the same Champion N-57G that it came with.

We were warned that Can-Am shift levers break readily, so we obtained a spare and gray-taped it to the handlebars. By now, the rust has probably welded it there. The original lever is still on the Can-Am, having been bent and rebent so many times that you wonder if it isn't really made of rubber. The brake and clutch levers do break easily, though. Of course, each time we break one, it's our fault. They don't break if you don't fall, yet it would be nice if they had more give.

Since the initial run in the Greenhorn, the T'NT has seen action in countless enduros, several motocrosses, and even a grinding two-hour GP. TEAM CYCLE WORLD has trophied on the Can-Am in each category. And when we didn't, it was the rider's fault.

The Can-Am's reputation is built mostly on its engine. A 175cc mill that produces in excess of 22 bhp, yet retains one of the broadest powerbands around, is quite a feat. But the handling deserves some praise, as well. Considering the fact that the bike is traditionally suspended in a world of forward-mounted everything, it performed adequately when new. But it wasn't long before the S&W shocks wore out from sheer abuse and the fork springs began to collapse. We replaced the shocks with Konis. They were worse than the worn S&Ws. So we took them apart and discovered badly scored pistons in the shocks. After replacing the pistons, the dampers came up to par. You expect a lot when you buy Konis and we were disappointed in the condition of our new shocks. Once repaired, all was forgiven, as control returned to the rear of the machine.

Control returned, but the rear end is still troublesome in one respect. It iacks the travel we have become accustomed to after riding several of the long-travel '75 models. Can-Am is working on this and has supplied an improved swinging arm set-up for our evaluations. See the accompanying sidebar for details.

The forks were much more trouble. Since there were no stock springs available from any of the Can-Am dealers near us, we obtained a pair of 20-in. 20-lb. springs from Webco. They said that these springs were a perfect fit in a pair of Betor forks like the Stockers on the T'NT. But they were far too stiff. We spoke with the Can-Am people and they said that the spring rate was correct, but that we should try 19-in. springs. These were much better. At least now we were back where we started. We had good fork action and control at the rear. And the engine was still churning merrily mile after mile.

We were getting ready for the Barstow-to-Vegas desert classic when, on the night before the race, we discovered that we were out of Torco oil. Since it was well past closing time at the local cycle shops, all we could do was fill up the rest of the injection tank with Klotz. Normally we wouldn't have done this, but after our experience in the Greenhorn, we knew that the engine probably wouldn't know the difference. It didn't.

Barstow-to-Vegas was the bike's only DNF. Trying to play follow-the-leader in dust as thick as soup, the Can-Am hit a rock that flattened the rear tire, not to mention the rim. But the engine continued to run.

The T'NT Can-Am models come with a 2.5-gal. tank, stock. On our 175, this was good for about 70 miles of enduro riding. The least mileage we ever got was 63 miles before going on reserve. The most was 80-plus riding on the street. Considering the performance, we'd say the mileage was average. In all of the events we've ridden, we've yet to run out of gas. Even in the problem-plagued Greenhorn. And you can almost forget about the oil. The main frame backbone doubles as an oil reservoir tank for the injection system. It holds 2.3-qt. of lubricant, enough for at least three, and sometimes four, tanks of gasoline.

Another advantage of the Can-Am is its adjustable steering angle. Our bike came set at one degree from maximum rake (30 degrees) which was pretty good. The front end pushed in the corners, but the extra rake gave us the high-speed stability we need for some of those California desert enduros.

The rear brake has been excellent since the first day. The front one didn't seat in completely until after some 300 miles had been put on the bike, although it did improve steadily until that point. Now, after more than 2000 miles of competition, they are nearly worn and will soon need replacing. Darn good mileage considering the elements. And they're virtually waterproof.

The engine is the same way. No amount of moisture seems able to seep in and disturb either the carburetor or the ignition. We've never had to set the timing and yet the bike has > never failed to start. We can't testify as to whether the kickstarter can absorb more than one tromp at a time, because we never had to give it more than that.

The present condition of our Can-Am is as follows. The rear rim still bears the scar of the encounter with the rock, although most of the damage has been hammered into submission. The neat Can-Am logo is almost gone from the tank, having been rubbed off by numerous pairs of racing leathers. The 3.50-21 Cheng Shin is still on the front wheel, although it should have been replaced a couple hundred miles ago. We've gone through four rear tires, the latest being a Dunlop 4.10-18 that has started to chunk badly. The best tire we found for the bike was a 4.25-18 Barum six-ply. It's a bit much for deep sand, but anywhere else it's perfect. We sheared one footpeg off, but a new one bolted right into place.

The ends of both levers are broken, but the levers are operable. A small leak has developed on the shift-shaft seal. A half hour and a couple of bucks should have that fixed. All three original cables—throttle, brake and clutch—are still on the bike and haven't frayed. The seat foam has lost some of its cushion, but the seat hasn't torn despite numerous get-offs.

As you can see, after our early troubles were diagnosed and remedied, our problems with the Can-Am have been few and minute. At the same time, the adventures we've had on the bike have been many, with lots more still to come. It has impressed all of us tremendously. So much, in fact, that one of our editors purchased the very same test bike. A stronger testimonial is hard to come by. ra

View Full Issue

View Full Issue