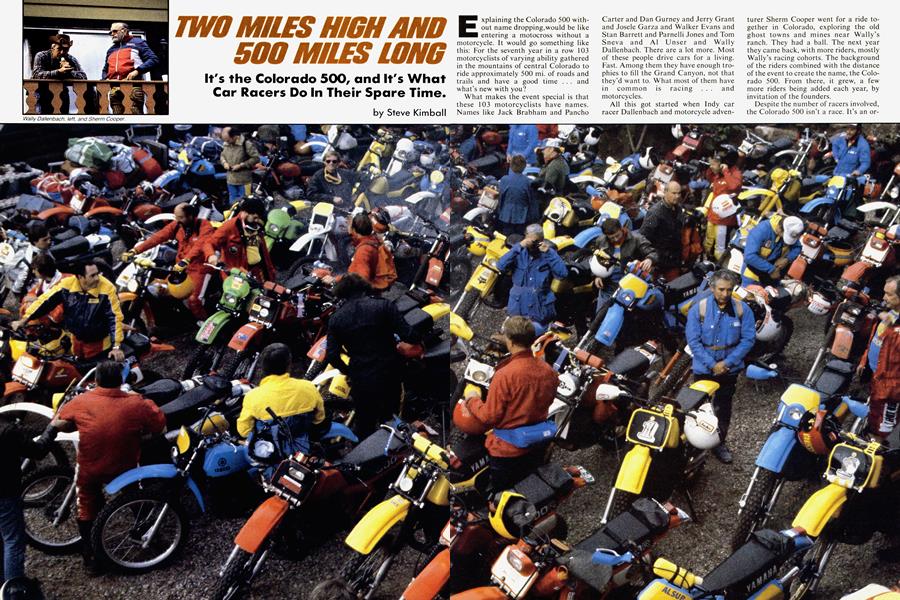

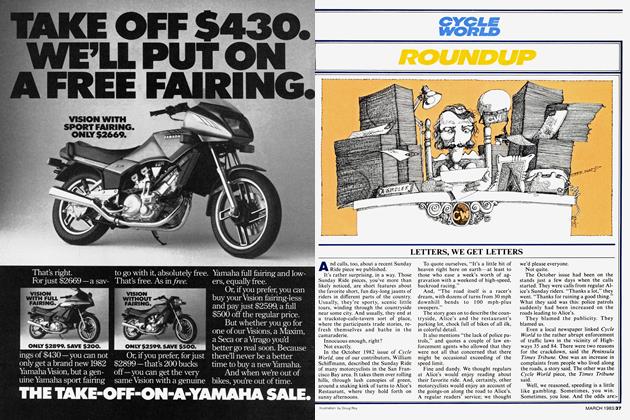

TWO MILES HIGH AND 500 MILES LONG

It's the Colorado 500, and It's What Car Racers Do In Their Spare Time.

Steve Kimball

Explaining the Colorado 500 without name dropping, would be like entering a motocross without a motorcycle. It would go something like this: For the seventh year in a row 103 motorcyclists of varying ability gathered in the mountains of central Colorado to ride approximately 500 mi. of roads and trails and have a good time . . . and what’s new with you?

What makes the event special is that these 103 motorcyclists have names. Names like Jack Brabham and Pancho Carter and Dan Gurney and Jerry Grant and Josele Garza and Walker Evans and Stan Barrett and Parnelli Jones and Tom Sneva and Al Unser and Wally Dallenbach. There are a lot more. Most of these people drive cars for a living. Fast. Among them they have enough trophies to fill the Grand Canyon, not that they’d want to. What most of them have in common is racing . . . and motorcycles.

All this got started when Indy car racer Dallenbach and motorcycle adventurer Sherm Cooper went for a ride together in Colorado, exploring the old ghost towns and mines near Wally’s ranch. They had a ball. The next year they came back, with more riders, mostly Wally’s racing cohorts. The background of the riders combined with the distance of the event to create the name, the Colorado 500. From there, it grew, a few more riders being added each year, by invitation of the founders.

Despite the number of racers involved, the Colorado 500 isn’t a race. It’s an organized trail ride. Riders show up at Wally’s ranch outside Basalt, Colorado with their motorcycles and gear. Only invited riders show up. How magazine reporters get invited has something to do with Jerry Grant and Champion spark plugs, but nobody explained it. At the sign-in riders get maps, instructions and lots of stickers. Leave your bike unattended for a few minutes and someone will plaster it with decals.

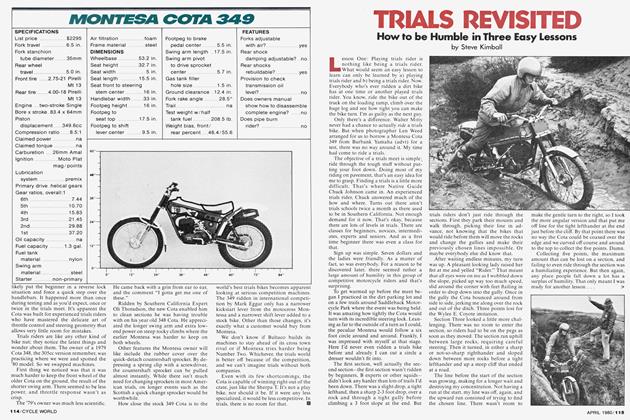

Monday is arrival day and tuning time. Dallenbach’s ranch is somewhere over 6000 ft. above sea level. That’s the lowest point on the ride. Several mountain passes will be over 13,000 ft. in elevation. This makes jetting changes important and a continual subject of concern for some riders. The bikes are mostly Honda XR500s and Yamaha YZ and IT465s and 490s. There are a handful of Huskys, a couple of KTMs, a couple of Kawasakis, a Maico and not much else. The bikes smaller than 400cc could all be loaded on one truck, or maybe a pickup and a trailer. The extreme elevation, according to Jerry Grant, makes the biggest motorcycle available just adequate.

To this collection of stars riding giant motorcycles, I brought a Cagiva 200, spiritual heir to the Harley-Davidson made in Italy. I also brought one Harley T-shirt for every day of the week, but nobody noticed. The motorcycle didn’t go unnoticed. What kind of bike is that, where’s it made, how big is it and why’d you bring that thing? Those were everybody’s questions. Most felt an uncontrollable urge to comment.

“That thing’s never going to make it over the passes around here,” laughed Grant. He offered to provide tow services for the steep passes, so he could haul it up behind his YZ490. His comments were typical. The consensus was that a 200cc anything was in trouble and a 200cc Italian motorcycle that’s never seen the inside of an American dealership and had no parts available anywhere would be hopelessly out paced.

My preparation amounted to bolting on a license plate, reducing the main jet by three sizes and moving the needle clip up a notch. With those changes the bike ran fine and felt good.

Not everyone believes the old adage, if it works don’t fix it. All manner of tinkering was apparent. Many of the Honda four-strokes had custom frames, but AÍ Unser’s even had a giant steel tube frame around the over-size headlight. He had a pack tied to the frame. It looked like a terrible place to add weight, but it made his red motorcycle stand out from the other red motorcycles. Dan Gurney has always been famous for trying things. When he raced he could fix a car so well it took the mechanics the whole night to return it to stock condition for the race. He’s chopped a street bike up and put the motor behind the rider for a lower center of gravity. His All American Eagle race cars have tried various new ideas and some of them work. His is an inventive mind. His YZ490 looked like the other 490 Yamahas, but his had a five-speed transmission. He also stops along the trail half a dozen times to make suspension adjustments. Perfection is hard to find.

While some of the riders couldn’t leave their bikes alone, others had surprisingly little mechanical skill. After the first day of riding at elevations up to and over 13,000 ft., Tom Sneva knew his YZ490 wasn’t running as well as it should, mostly at low and medium engine speeds. Someone told him the needle should be moved down a notch. The only problem was that he didn’t know exactly what the needle was or how to move it. Before he raced Indy cars for a living, Sneva taught school. He seems too cheerful to have ever been a school teacher. With a little help he had the carburetor apart and the needle moved.

Shared traits are uncommon is this group. The youngest riders were teenagers, like Wally’s son or Jack Brabham’s sons. The oldest riders were retirement-age grandfathers. Some were soft spoken and uncomfortable making speeches, like Al Unser who was called on to present one of the donations made by the group to local schools. Others, like Ak Miller, come alive with an audience and like to perform. Though these men, because of their skills, have become public figures, they haven’t set out to become celebrities. They are comfortable among their friends, courteous to fans, and intensely knowledgeable in their specialties.

George Heneghan, a successful architect and one of the Hawaii contingent, commented that the riders of the Colorado 500 were men who could do anything in the world they wanted to do. Once a year they come to Colorado and ride dirt bikes because of the satisfaction they get from the experience. Their outside activities are participant sports and they love engines. About half the people I talked to don’t just race cars and ride motorcycles, but fly airplanes, ski and travel extensively.

Sherm Cooper, who organizes the ride with Wally, has ridden motorcycles across Africa six times. That’s not the only continent he’s explored, but he finds it fascinating. On his last trip through Africa he met Patrick Hsu, a retired shipping magnate and invited him on the Colorado 500. Hsu went back to his home on Hawaii, learned how to ride a dirt bike and joined the group a year ago. This year he was back with more skill and a new bike.

Something is shared by all these people, besides the enjoyment of motorcycling. Call it a hunger for competition. Jerry Grant demonstrated it wneu he rode along the flat, smooth, twisting dirt road out of Ouray. He started off riding his YZ easily enough, but that didn’t last long. He saw someone in front and had to go a little faster and pass. Then there was another rider and a little more speed and before long he was sliding off the road on a corner, killing his engine. A few minutes later here he came again, sliding off corners again. By the first stop Grant was in front, not as a result of skill or machinery, he just couldn’t follow anyone. He couldn’t be second. That’s what made him the first man to drive 200 mph at Indy, and it made him ride the knobs off his YZ in Colorado.

That same spirit for Mike Chandler means he can’t ride street bikes. On his YZ he looks at ease, wheelying at will, sliding it around corners, looking like someone who has spent years racing motocross bikes, which he has. He also races Indy cars for Gurney. He wants to win the Indy 500 and the Indy car championship. But the only time he rode his dad’s breathed-on CBX up a mountain road, he found that the only way he has ever ridden a motorcycle is with the throttle wide open and that’s the only way he will ride. He can’t back off on a street bike any more than Grant can on a motocrosser, and instead of scaring people on the street, he has decided to limit his thrills to dirt bikes and race cars.

A number of old motorcycle racers— make that racers of old motorcycles— are in the group. Jim Hunter rode BSAs in AMA racing a generation ago. Ernie Beckman was the last man to win an AMA National on an Indian. He was a member of the Indian wrecking crew that gave Harley-Davidson such a struggle just before Indian folded. Bill Bell is here, too, being introduced as Mike Bell’s dad. His own racing and bikebuilding talents aren’t as significant as his son’s achievements now. Jack Brabham is still introduced as Jack Brabham, three times world driving champion. He’s accompanied by two of his sons, including current racer Geoff Brabham. He may not have many more years of his own fame, the way his son is racing.

Three generations of racers make the riders. On the last night of the ride there’s one final event, an awards banquet. Trophies are given out for such things as most improved rider (Patrick Hsu), most helpful rider (John Russell), rider of the year (Dennis Agajanian). Dallenbach and Cooper pass out the awards and Dallenbach introduces Ak Miller.

Ak was building V-Eight powered hot rods to race against Ferraris back in the Fifties. He was also sticking American engines in little foreign cars to race at Pike’s Peak, and sticking jet motors on wheels to race at Bonneville. Dallenbach tells us that Miller was his hero when he was in high school reading about cars and racing. Who was Miller’s hero back in the Thirties? And were Josele Garza and Chandler inspired by Dallenbach or Grant? Will the kids who read about Garza and Chandler and Geoff Brabham become motorheads and produce their own heros?

Getting to the dinner that night brought some of this home. Between Crested Butte and Aspen are many roads and trails. The easy way, according to Wally, is through Schofield Pass. A slightly hard route was listed on the route sheet and then there was something labeled “Hardest but quickest. (May God have mercy on your body) South on Rt. 135 to Rd. 738 to left fork up and across Pearl Pass. (Ugh! Ouch! Ohhh!) down across snowfield to rock pile trail (say your prayers).”

All the emphasis seemed exaggerated as the trail left the road, wound through fields, forded a couple of rivers, only one of which was deep enough for swimming.

I started out in a small group of three, but found myself alone by the time the trail turned to shale and boulders and the cows were blocking the rock pile. By that time the elevation was something around 1 2,000 ft. or so, the air was cool and the breathing hard.

Another mile and the trail got tough. The boulders were big enough and the trail steep enough that the Cagiva only wanted to spin the rear tire when it was spun so fast it had enough power. I got off the bike and ran it up the rock pile about 50 yards, until all the lessons about density altitude had made themselves painfully clear. It was time for a rest. There were no trees at this elevation. Just a few hundred yards up the trail was the peak, over 13,000 ft. above sea level. After a 10 min. rest it was time for another run beside the bike and around the biggest boulders of the steepest part of the trail, then another rest. Down in the valley were bikes heading up the trail, sending their rumbling noise up to the peak as some kind of warning. When they got in sight my questions about making it over the peak disappeared. I fired up the Cagiva, held the throttle open and popped the clutch in and out, in and out, keeping the rear wheel under control and the bike moving while the pack of big red and yellow bikes got closer. One bike gets around before the peak and I pull over at the top and let the next rider past. It’s Gurney.

Just as Wally Dallenbach’s hero was Ak Miller, Dan Gurney was the racer I’ve always followed. It was the 1963 Indianapolis 500 when he and Jimmy Clark raced the first back motor Lotus Fords that racing became exciting for me. Gurney got seventh, I think, and Clark second. Gurney went on to win formula I races and USAC races and all kinds of other races. He’s become a car builder of note, the All-American Eagles being the cars to beat for a while.

Other racers have been as exciting. Dick Mann was like that. Whatever he did was just more exciting than when somebody else did the same. It was never because Mann or Gurney were more talented than other racers. Gurney probably never was the driver that Jimmy Clark was, but he brought something to his racing, a cleverness, a perseverence, that made him seem like the kind of person I could be.

Going down Pearl Pass, I followed Gurney for a while. He was going just a little slower than I wanted to go. He didn’t want to lace. Neither did I. Until he looked back and moved over, I was content to follow him. I was still rooting for him, wanting him in front. When someone else came up from the rear, I passed and went on down the hill.

On the freeway back to California early that Saturday morning someone came up from behind, flashed the headlights, and pulled around to pass. It was Gurney. He waved as he went past, a big grin on his face.

How nice it is when the heroes you chose 20 years ago turn out to be worth it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue