MIDNIGHT RUN

CRAZY ON THE CROTONA

JON F. THOMPSON

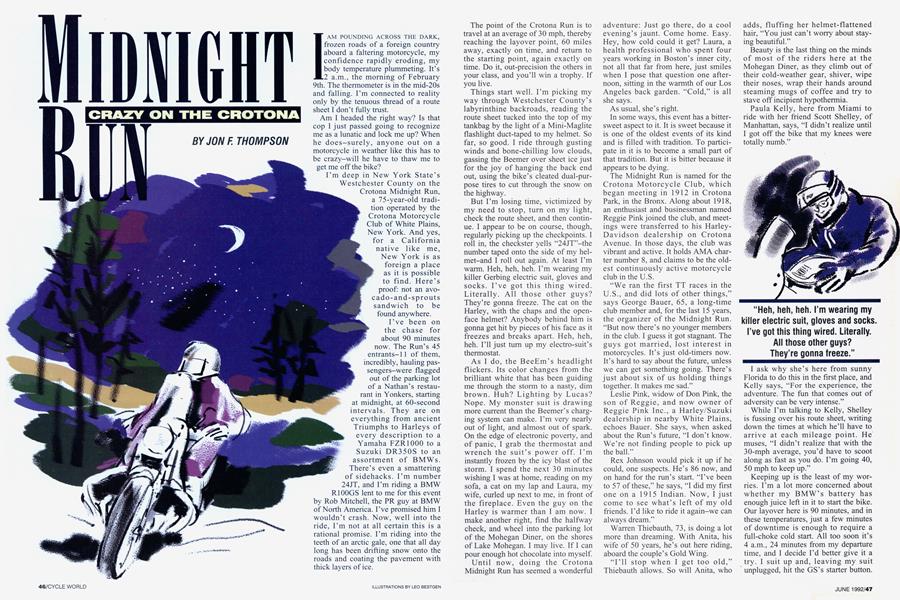

I AM POUNDING ACROSS THE DARK, frozen roads of a foreign country aboard a faltering motorcycle, my confidence rapidly eroding, my body temperature plummeting. It’s

2 a.m., the morning of February 9th. The thermometer is in the mid-20s and falling. I’m connected to reality only by the tenuous thread of a route sheet I don’t fully trust.

Am I headed the right way? Is that cop I just passed going to recognize me as a lunatic and lock me up? When he does-surely, anyone out on a motorcycle in weather like this has to be crazy-will he have to thaw me to get me off the bike?

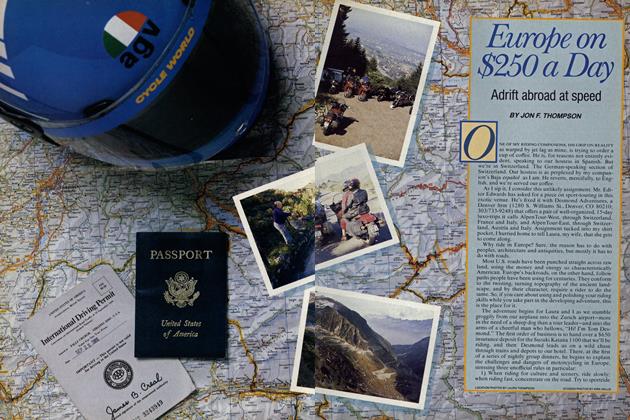

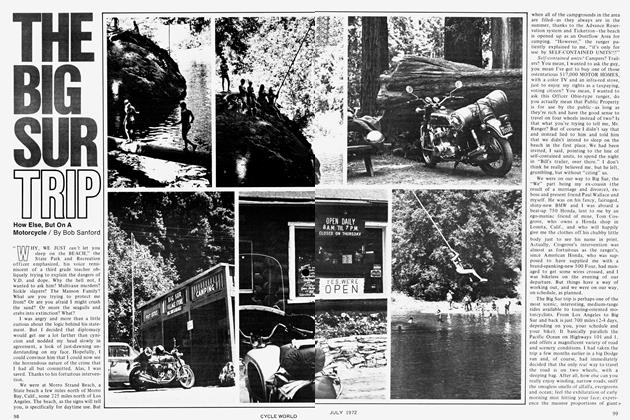

I’m deep in New York State’s Westchester County on the Crotona Midnight Run, a 75-year-old tradition operated by the Crotona Motorcycle Club of White Plains, New York. And yes, for a California native like me, New York is as foreign a place as it is possible to find. Here’s proof: not an avocado-and-sprouts sandwich to be found anywhere. I’ve been on the chase for about 90 minutes now. The Run’s 45 entrants-11 of them, incredibly, hauling passengers-were flagged out of the parking lot of a Nathan’s restaurant in Yonkers, starting at midnight, at 60-second intervals. They are on everything from ancient Triumphs to Harleys of every description to a Yamaha FZR1000 to a Suzuki DR350S to an assortment of BMWs. There’s even a smattering of sidehacks. I’m number 24JT, and I’m riding a BMW R100GS lent to me for this event by Rob Mitchell, the PR guy at BMW of North America. I’ve promised him I wouldn’t crash. Now, well into the ride, I’m not at all certain this is a rational promise. I’m riding into the teeth of an arctic gale, one that all day long has been drifting snow onto the roads and coating the pavement with thick layers of ice.

The point of the Crotona Run is to travel at an average of 30 mph, thereby reaching the layover point, 60 miles away, exactly on time, and return to the starting point, again exactly on time. Do it, out-precision the others in your class, and you’ll win a trophy. If you live.

Things start well. I’m picking my way through Westchester County’s labyrinthine backroads, reading the route sheet tucked into the top of my tankbag by the light of a Mini-Maglite flashlight duct-taped to my helmet. So far, so good. I ride through gusting winds and bone-chilling low clouds, gassing the Beemer over sheet ice just for the joy of hanging the back end out, using the bike’s cleated dual-purpose tires to cut through the snow on the highway.

But I’m losing time, victimized by my need to stop, turn on my light, check the route sheet, and then continue. I appear to be on course, though, regularly picking up the checkpoints. I roll in, the checkster yells “24JT”-the number taped onto the side of my helmet-and I roll out again. At least I’m warm. Heh, heh, heh. I’m wearing my killer Gerbing electric suit, gloves and socks. I’ve got this thing wired. Literally. All those other guys? They’re gonna freeze. The cat on the Harley, with the chaps and the openface helmet? Anybody behind him is gonna get hit by pieces of his face as it freezes and breaks apart. Heh, heh, heh. I’ll just turn up my electro-suit’s thermostat.

As I do, the BeeEm’s headlight flickers. Its color changes from the brilliant white that has been guiding me through the storm to a nasty, dim brown. Huh? Lighting by Lucas? Nope. My monster suit is drawing more current than the Beemer’s charging system can make. I’m very nearly out of light, and almost out of spark. On the edge of electronic poverty, and of panic, I grab the thermostat and wrench the suit’s power off. I’m instantly frozen by the icy blast of the storm. I spend the next 30 minutes wishing I was at home, reading on my sofa, a cat on my lap and Laura, my wife, curled up next to me, in front of the fireplace. Even the guy on the Harley is warmer than I am now. I make another right, find the halfway check, and wheel into the parking lot of the Mohegan Diner, on the shores of Lake Mohegan. I may live. If I can pour enough hot chocolate into myself.

Until now, doing the Crotona Midnight Run has seemed a wonderful adventure: Just go there, do a cool evening’s jaunt. Come home. Easy. Hey, how cold could it get? Laura, a health professional who spent four years working in Boston’s inner city, not all that far from here, just smiles when I pose that question one afternoon, sitting in the warmth of our Los Angeles back garden. “Cold,” is all she says.

As usual, she’s right.

In some ways, this event has a bittersweet aspect to it. It is sweet because it is one of the oldest events of its kind and is filled with tradition. To participate in it is to become a small part of that tradition. But it is bitter because it appears to be dying.

The Midnight Run is named for the Crotona Motorcycle Club, which began meeting in 1912 in Crotona Park, in the Bronx. Along about 1918, an enthusiast and businessman named Reggie Pink joined the club, and meetings were transferred to his HarleyDavidson dealership on Crotona Avenue. In those days, the club was vibrant and active. It holds AMA charter number 8, and claims to be the oldest continuously active motorcycle club in the U.S.

“We ran the first TT races in the U.S., and did lots of other things,” says George Bauer, 65, a long-time club member and, for the last 15 years, the organizer of the Midnight Run. “But now there’s no younger members in the club. I guess it got stagnant. The guys got married, lost interest in motorcycles. It’s just old-timers now. It’s hard to say about the future, unless we can get something going. There’s just about six of us holding things together. It makes me sad.”

Leslie Pink, widow of Don Pink, the son of Reggie, and now owner of Reggie Pink Inc., a Harley/Suzuki dealership in nearby White Plains, echoes Bauer. She says, when asked about the Run’s future, “I don’t know. We’re not finding people to pick up the ball.”

Rex Johnson would pick it up if he could, one suspects. He’s 86 now, and on hand for the run’s start. “I’ve been to 57 of these,” he says, “I did my first one on a 1915 Indian. Now, I just come to see what’s left of my old friends. I’d like to ride it again-we can always dream.”

Warren Thiebauth, 73, is doing a lot more than dreaming. With Anita, his wife of 50 years, he’s out here riding, aboard the couple’s Gold Wing.

“I’ll stop when I get too old,” Thiebauth allows. So will Anita, who

adds, fluffing her helmet-flattened hair, “You just can’t worry about staying beautiful.”

Beauty is the last thing on the minds of most of the riders here at the Mohegan Diner, as they climb out of their cold-weather gear, shiver, wipe their noses, wrap their hands around steaming mugs of coffee and try to stave off incipient hypothermia.

Paula Kelly, here from Miami to ride with her friend Scott Shelley, of Manhattan, says, “I didn’t realize until I got off the bike that my knees were totally numb.”

I ask why she’s here from sunny Florida to do this in the first place, and Kelly says, “For the experience, the adventure. The fun that comes out of adversity can be very intense.”

While I’m talking to Kelly, Shelley is fussing over his route sheet, writing down the times at which he’ll have to arrive at each mileage point. He muses, “I didn’t realize that with the 30-mph average, you’d have to scoot along as fast as you do. I’m going 40, 50 mph to keep up.”

Keeping up is the least of my worries. I’m a lot more concerned about whether my BMW’s battery has enough juice left in it to start the bike. Our layover here is 90 minutes, and in these temperatures, just a few minutes of downtime is enough to require a full-choke cold start. All too soon it’s 4 a.m., 24 minutes from my departure time, and I decide I’d better give it a try. I suit up and, leaving my suit unplugged, hit the GS’s starter button.

It cranks once, stops, cranks again, and fires. Outstanding! I let it run for a minute on full-choke, and then knock it back to half-choke. It immediately sputters and dies. I try again, and am greeted only by a reluctant clatter from the bike’s starter solenoid. I try a bump-start on the frozen parking lot pavement. No dice. I try again. Again, no dice. With help from one of the starters, I try yet again. Still no fire.

Shelly and Kelly, loading up, see that I’m in trouble. He hands me a set of mini jumper cables, of all things, and says, “Here, I’ll get ’em back from you at the end of this.”

I’m saved! I cadge a jump from an onlooker’s van, get the BeeEm fired, keep the revs up and the choke on, and take my start at 4:24 sharp. I’m going to make this, or freeze to death trying.

It’s colder now. The storm clouds have blown on eastward into Connecticut and the Long Island Sound, revealing a heaven filled with stars that glitter against the universe’s black depths like chunks of radioactive party ice. The clouds have held in at least a bit of residual warmth, and with them gone, the temperature rockets downward. My fingers no longer are numb. Now, they ache, right down to the bone. They feel frozen solid. If I move them will they shatter like icicles?

Then I remember. This bike has electrically heated handgrips. Bless BMW! I flip the rocker switch to Full Nuke and within minutes feel the warmth flow into my fingers. Hah! Piece of cake.

But not for everybody. Far out in the dark countryside, I come upon a pair of Gold Wings pulled to the side of the road. I stop and yell, “Everyone okay?”

“We’re okay,” comes the answer, “we’ve just got generator problems, so we’re gonna swap stators and see if that helps. Thanks for stopping.” Good. The last thing I want to do is shut my bike off to assist in the repairs, since I’ve got my own brand of electrical problems. So I gas it, feeling only a little guilty.

Once again into the rhythm of the event, I find that I’ve relaxed enough to find a perverse pleasure in cruising through this bitterly cold night, past darkened homes, through hardwood forests overseen by the ghosts of Algonquin and Iroquois warriors, through countryside trapped and later farmed since the area was colonized as New Netherland by the Dutch West India Company in 1621.

Even the route sheet has become my friend. I began this ride by seeing it as a sly trickster, filled with traps waiting to get me lost in this historic and honorable countryside. But now I settle in and see it for what it is: a benevolent helper willing to guide me all the way to the event’s conclusion. All I’ve got to do is pay attention and do what it says. Soon, even with the stops I make to check directions, I find I’ve caught up with another rider. I recognize him as a Gold Wing pilot flagged off just ahead of me. I’m ahead of schedule. I roll out, concentrate on staying a minute behind him and on my directions.

My sheet reads, “33.2, left Route 35, traffic light; 35.2, right Route 124; 35.6, right Route 124,” and I’m so intent on my navigation, and on the fading light from my flashlight, that it takes me a while to notice a mild glow from the east. It’s-no, it can’t be, not already. But it is. The first hint of the coming dawn. As I execute the final few instructions over the Bronx River Parkway and from there, onto Central Park Avenue, dawn becomes day. With the first rays of thin, watery sunlight, I realize that I’m nearly at the end of the 75th Crotona Midnight Run.

I work my way through the last few traffic lights and make a left into the Nathan’s parking lot, keyed up, yet exhausted.

“It’s 24JT,” sings the timekeeper, as his assistant writes down my number and arrival time.

And now, celebration? Nope. It’ll take a week to calculate results, Bauer tells me. Those results ultimately reveal that Piet Booanstra was the cleverest timekeeper, and has won the event with 995 points out of a possible 1000. Me? I’m out of it. I finished seventh, with 992 points. Meanwhile, the digital temperature sign on a nearby gas station reads 13 degrees. Everyone is too cold, and too tired, to celebrate. They check in and head for home. And that’s what I do, caring more about grabbing a hot bath than about who finished where in this event, completely forgetting that I’ve still got Scott Shelley’s jumper cables in my tankbag. I remember this, finally, back in my hotel parking lot. I stash the bike, grab the keys to my U-Wreck-It, and head back, all the time berating the car heater for not being more powerful. Too late. I’ve missed Shelley. I’m in time only to see the sweep truck arrive, long after the final rider has checked in and gone home. I owe you one, Scott. In fact, I owe you two.

I also owe Paula for her observation about the intensity of the fun that comes from adversity. Because she’s right. The Crotona Midnight Run may have been cold, and it may have been intense, but it also was a whole lot of fun.

There’s just one thing, Scott: To collect, you’ve gotta come to California. I’m not coming anywhere near New York. Not while it’s still winter. Not even with an electric suit. m