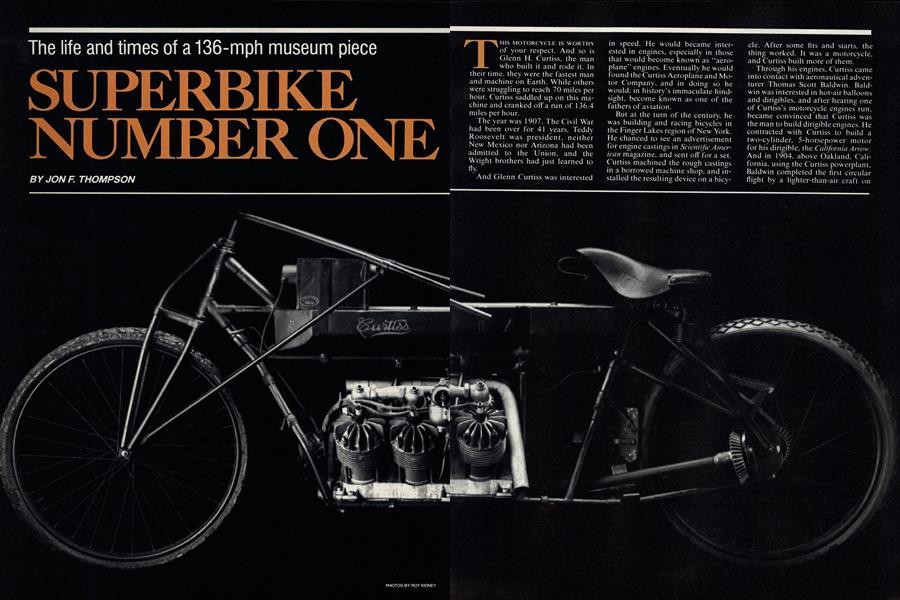

SUPERBIKE NUMBER ONE

The life and times of a 136-mph museum piece

JON F. THOMPSON

THIS MOTORCYCLE IS WORTHY of your respect. And so is Glenn H. Curtiss. the man who built it and rode it. In their time, they were the fastest man and machine on Earth. While others were struggling to reach 70 miles per hour, Curtiss saddled up on this machine and cranked off a run of 136.4 miles per hour.

The year was 1907. The Civil War had been over for 41 years, Teddy Roosevelt was president, neither New Mexico nor Arizona had been admitted to the Union, and the Wright brothers had just learned to fly.

And Glenn Curtiss was interested in speed. He would became interested in engines, especially in those that would become known as “aeroplane” engines. Eventually he would found the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company, and in doing so he would, in history’s immaculate hindsight, become known as one of the fathers of aviation.

But at the turn of the century, he was building and racing bicycles in the Finger Lakes region of New York. He chanced to see an advertisement for engine castings in Scientific American magazine, and sent off for a set. Curtiss machined the rough castings in a borrowed machine shop, and installed the resulting device on a bicycle. After some fits and starts, the thing worked. It was a motorcycle, and Curtiss built more of them.

Through his engines, Curtiss came into contact with aeronautical adventurer Thomas Scott Baldwin. Baldwin was interested in hot-air balloons and dirigibles, and after hearing one of Curtiss’s motorcycle engines run, became convinced that Curtiss was the man to build dirigible engines. He contracted with Curtiss to build a two-cylinder, 5-horsepower motor for his dirigible, the California Arrow. And in 1904, above Oakland, California, using the Curtiss powerplant, Baldwin completed the first circular flight by a lighter-than-air craft on the North American continent.

Asked what had made his flight a success, Thomas is reported to have replied, “It was the motor.”

But if Baldwin was pleased with the California Arrow's engine, he was thrilled with the engine Curtiss built for a subsequent dirigible. The City of Los Angeles. This was a V-Eight which produced 1 8 horsepower, and was so successful that in 1906, Baldwin commissioned another V-Eight, one which ultimately would pump out 40 horsepower.

And all this time, Curtiss, by all accounts a withdrawn, sober man. remained as consumed with racing as he was with building aircraft engines. At the 1906 Syracuse State Fair, he established, according to biographers Robert Scharff and Walter S. Taylor, a world motorcycle record when he thundered around a mile flat-track in 6 1 seconds.

But there was more to come. Curt iss's passion for motorcycle speed and for promoting his company led him in January of 1907 to Ormond Beach, Florida, for the Florida Speed Carnival, the spiritual progenitor of today’s Daytona Beach Speed Week.

According to another Curtiss biographer. C.R. Roseberry, Curtiss was there because he wondered what the 40-horsepower V-Eight destined for one of Baldwin’s airships would do if bolted into a motorcycle frame. So he called for the construction of a chassis that would carry the engine, and the result was the spindly creation you see on these pages.

Now in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum, the chassis is more than 84 inches long. Because of the wide splay of the engine’s cylinder banks, the beast was given a handlebar long enough to enable Curtiss to sit at the bike’s rear, behind that massive motor, and still steer it.

Ed Marshall, museum specialist in charge of the collection, and a fan of classic bikes, says the frame appears to be sweated and brazed together in the manner of vintage Indians and others. “It is very stout,” he says.

Somewhat less stout was the finaldrive arrangement, a shaft from the crankshaft to a pair of exposed bevel gears which drove the rear wheel. This set-up was said to have been rendered unusable after the machine’s record run along the beach. The rear wheel carried an automobile tire, while a heavy-duty motorcycle wheel and tire were used at the front.

The only brake evident on the machine is a crude, lever-action affair which exerts pressure on the tread of the rear tire.

But Curtiss intended the machine to go, not to stop, and after several passes on smaller bikes, he rolled out the V-Eight-powered brute and gofa push-start from his helpers. Reports note that he began his 3-mile run wearing a leather jacket and helmet, but no goggles, and, getting up to speed, he blasted between the pilings of a pier, reflexively pulling in his elbows as he did so, before rocketing onto the measured mile.

The run was over soon enough. Timers had caught his single pass at an incredible 136.4 miles per hour. Roseberry’s book quotes Curtiss as saying of his run, “It satisfied my speed-craving.”

By all reports, Curtiss never again rode the record-breaking machine. Its engine was removed and delivered to Baldwin, and was replaced with the pistonless, rodless, dummy the bike’s frame now carries.

The Smithsonian’s Ed Marshall is unsure about the bike’s middle history, and Curtiss’ biographers, who dwell upon the man’s engineering and aeronautic achievements, don’t shed much light on the subject. Roseberry reports that Curtiss kept the machine first at his home, and then, for a time, displayed it in the lobby of a Curtiss-owned aircraft plant, but little else is known. Marshall, whose specialty is display and restoration of equipment, is unsure how the machine came into the Smithsonian’s collection. And he says because it is a land vehicle in an aeronautical museum, it’s unlikely the big Curtiss ever will be displayed on its own, though it could be used in a collateral display of other Curtiss artifacts. But Marshall adds, “If anyone wanted to see it, they’d surely have a right to see it.”

And Marshall would know just where to find it. An enthusiastic owner/restorer of Indian and Matchless motorcycles, Marshall keeps the Curtiss right by his desk, in the Smithsonian’s Garber Storage Facility in Maryland. He has, he says, offered to do a restoration of the machine, which he says would not be a full restoration, but would maintain original paint and decals where possible. But that’s at least a couple years down the road, and may never come to pass, he admits.

And perhaps that’s for the best, as the thought of restoration seems almost sacrilegious. This is an honest artifact of a simple time when a visionary went onto a beach to push the limits of the performance envelope— not justof motorcycles, but of all wheeled vehicles. Though the famous Blitzen-Benz racing car went a few miles per hour faster in 191 l, no motorcycle went faster until 1930, when one Joe Wright, mounted upon an OEC-Temple, went 137.23 miles per hour at Arpajon, France.

Preserve the Curtiss V-Eight in its current form? By all means. It is, after all, an original, just as was its builder and rider. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

April 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

April 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

April 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupMichelin Pulls Out of U.S. Bike-Tire Market

April 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupWhite Power Reinvents the Fork

April 1990 By Alan Cathcart