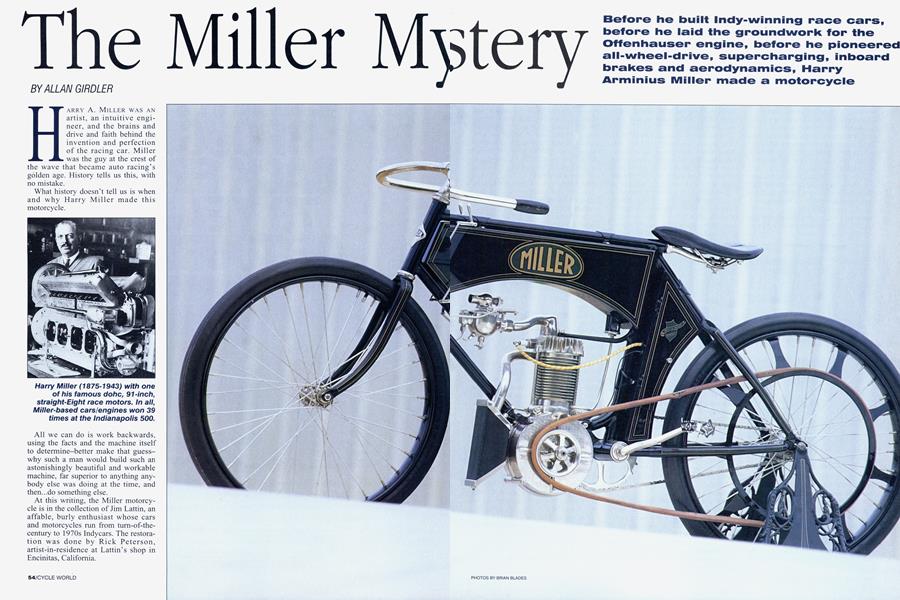

The Miller MYstery

ALLAN GIRDLER

HARRY A. MILLER WAS AN artist, an intuitive engineer, and the brains and drive and faith behind the invention and perfection of the racing car. Miller was the guy at the crest of the wave that became auto racing's golden age. History tells us this, with no mistake.

What history doesn't tell us is when and why Harry Miller made this motorcycle.

All we can do is work backwards, using the facts and the machine itself to determine-better make that guesswhy such a man would build such an astonishingly beautiful and workable machine, far superior to anything anybody else was doing at the time, and then...do something else. At this writing, the Miller motorcycle is in the collection of Jim Lattin, an affable, burly enthusiast whose cars and motorcycles run from tum-of-thecentury to 1970s Indycars. The restoration was done by Rick Peterson, artist-in-residence at Lattin’s shop in Encinitas, California.

Lattin got the Miller-looking not at all like it looks here-from a man named Guy Jones, who lives in Massachusetts, works in railroad construction and travels to the literal comers of the U.S. At one such comer, a wooden gas station in rural Maine several years ago, Jones spotted the remains of an obviously antique motorcycle. The guys at the station knew nothing about it, nor did they care. But on one happy and lucky day, Jones stopped by the station when the owners were getting ready to tear the place down and clear out all the junk. Yes. Including the old motorcycle.

Jones got it. Minus wheels, because somebody in the neighborhood had taken them off years before and put them on a garden cart, as in, heck, why not, the old cycle didn’t run anyway? But small towns are known for not much happening and for everybody knowing what everybody else is up to,

so a few dollars changed hands and, presto, the wheels came off the cart and were part of the deal.

Jones was happy to save the motorcycle. As rescued, its paint was intact, so the name and emblem could easily be read. Jones was surprised, as will most of us be, to get some hint that Harry Miller, best known for his supercharged 91-cubic-inch racing cars, the ones that lapped the board tracks at 140-plus in the 1920s and dominated at the Brickyard, had ever had anything to do with motorcycles.

Lattin’s collection includes a couple of Miller cars. He’s plugged into the subculture, so rumors led him to Jones, and in exchange for more money than he likes to discuss, Lattin got the weathered old Miller motorcycle. The major challenge, he says now, wasn’t matching the paint or making the parts. It was working out what Miller had in mind when he did what he did. And why. And when.

Facts: Harry Miller was born in Menomonie, Wisconsin, in 1875. His father was a schoolteacher and was understandably distressed when young Harry quit school at 13 and got a job in the town’s lone machine shop. He left home at 17 and two years later was in Los Angeles, at that time the hotbed of racing, as in bicycle racing. Miller became the Mike Velasco or Vance & Hines or Tom Sifton of his place and time, taking stock bicycles and making them into racing bicycles. He met a wonderful girl and soon as they were of age, they got married (it was a long and very happy marriage, one can’t resist adding here). In 1897, Harry took Edna back to Wisconsin to meet his family, and he took a job in Menomonie.

The date is important, because while there were no notes being taken, while the media wasn’t yet following Harry Miller around, author/historian Griff Borgeson was told by Edna Miller that in 1897 Harry needed to get to work and installed an engine on a bicycle, a project which if verified would makeq that machine just about the first motorcycle made in America.

Miller liked making money and spending it on his wife and his projects. He liked new ideas. What he wasn’t as keen on was doing the same thing over and over, even if he could profit from it. To illustrate that, Borgeson quotes from a 1937 newspaper story that in 1898, while still in Wisconsin, Miller built a four-cylinder engine, clamped it to a rowboat and went cruising around the lakes. It was the first gasoline-powered outboard motor. But that was all Miller did with it. Another machinist in the same shop built a twin-cylinder outboard motor shortly after Miller’s. His name-pause for dramatic effect-was Ole Evinrude, and the rest is history.

But Miller was too busy for that. In 1900, he and Edna moved to San Francisco where some time later-again quoting from recollections-he built another motorcycle to get around on. Miller was also learning more about casting and production. He was the first in the U.S. to make aluminum pistons, then he devised a new and better sparkplug, which he sold for a good sum. In 1905 he built his first car, then came up with a better carburetor and then an engine so good Ettore Bugatti-yes, that legend-acquired a Miller and happily copied Harry’s ideas for his own engines.

Miller went on to greater triumphs, while motorcycles disappear from his accounts and, presumably, his interests. But nearly a century later, we can look at the machine here and appreciate what Harry Miller did.

The first full stop surely must come from the sheer artistry displayed by the project. The Miller is in perfect balance and proportion. There are straight lines and there are curves, to blend and emphasize the unity of this motorcycle and the theme is carried as far as it can be. Witness the shape of the object in front of the crankcase: In case you didn’t guess, that’s the muffler.

Didn’t some philosopher say something about how the genius is in the details?

Look at the care taken with the details here: the classic taper of the shaft that carries the seat, the shape of the upper engine mount, the deft curve of the upper trailing frame tubes where they bifurcate from the top tube. The Miller emblem on the steering head is a casting, where the average maker then used a stamping, and this casting is near-on perfect.

As for the overall design, there’s no doubt Harry Miller made bicycles. There's equally no doubt that this machine never was one. This is no conversion; it must have been born a motorcycle, as in this frame was built and designed to hold this engine. That wasn't always so. In 1901, Oscar Hedstrom, who was also a racing bicy cle builder, constructed the prototype Indian. Hedstrom did the logical thing, especially as his sponsor, George Hendee, was a bicycle manufacturer who wanted to expand. Hedstrom built a bicycle, diamond-type frame with sprocket and pedals at the center of the frame's vee. Then he mounted the engine above that. It was a bicycle with engine added.

When Harley and Davidson unveiled their working prototype in 1902, they used a frame with a lower loop for the engine. The engine was better accom modated within the bicycle's frame. But this Miller's frame won't work unless it has an engine in it. This is what came to be called a Keystone frame, with the engine's cases bridging a gap in the tubes. This machine is not and never was a bicycle.

The engine: The design is classic turn-of-the-century. It's a four-stroke Single displacing 23.80 cubic inches (3 90cc), with the valves and sparkplug sharing a chamber to one side of the cylinder and piston, a textbook exampie of Intake Over Exhaust, or IOE. This was the design DeDion used in France, which was imported to the U.S. and adopted and adapted by Harley and Indian and countless others.

The Miller's intake system is also of the pioneer era in that the intake valve is opened by atmospheric pressure on the intake stroke and closed by pressure in the cylinder on the compression stroke. It wasn't that the engineers then didn't know about intake cams, they reasoned that air pressure would provide-wait for it!-variable valve timing. Which it did, at the rev limits of the day, which were in the high three figures.

The carburetor is from Schebler, a famous name back then, and the patent claims list 1901. That date may be very important, as we'll see.

Ignition is points, housed under the cylindrical cover on the engine's right, just below the cylinder and outboard of the crankshaft. A constant-loss battery and the coil are in the fabricated box behind the engine and mounted to the frame's central downtube.

We've met the muffler. Note that the handlebar grips are there only for gripping. No controls, Glenn Curtiss not having invented the twistgrip by 1897 or 1903, whichever year this Miller was built. There are only two controls, those shaped and polished levers on the frame backbone. The left is to set the throttle, the right the spark timing.

The engine cases are cast iron, beauti fully cast and polished. Where there is plating, it's nickel, chrome also not having been invented yet. The cast iron is a clue, by the way. Miller was, as mentioned, one of the early users of aluminum alloy. But just about all the firms casting engines had switched from iron to aluminum by 1900, so if this engine was cast in, say, 1902 or ’03, it would have been behind the times.

Drive is direct and fully locked, another feature more suited to 1897 than to 1903. There’s a pulley on the engine and a pulley on the rear wheel. They are joined by a leather belt. The belt is always tight, so when the engine revolves, so does the rear wheel, and vice versa. Pedal away, the engine spins and-when things are right-fires up and takes over the job of propelling the machine, with the rider proceeding at a set pace from one stop to the next, adjusting the throttle and spark levers to suit, oh, a hill or a curve.

The pedals would freewheel, sort of, because there’s a coaster brake in the rear hub. Not just any brake, either, but one of Miller’s own design and construction. The brake works well, now that Lattin has figured out how it works and how to rebuild it.

Even so, the locked drive is awkward. This was a drawback, obvious even back in pioneer days. Harley and Davidson fitted a tensioner so the belt could be slacked and the engine kept running when the bike was stopped. Indian used a lifter, so the exhaust valve could be held open until the rider had pedalled the machine to fire-up speed. You’d think Miller would have incorporated some sort of clutch or tensioner or something in 1903. On the other hand, Mrs. Miller recalled that when he built his first car, in 1905, it had a dog clutch, in or out, so the engine couldn’t revolve unless the car was moving. Made for interesting starts and stops, she said years later, but it could simply mean starting and stopping didn’t interest Miller nearly as much as going did.

You say that at least 90 years have passed since this machine was built, and while we search for clues and/or proof of this theory or that, we have to keep in mind that there could have been changes in the specification?

Lattin says no, or at least that he can find no evidence. If that post-1900 Schebler carburetor was installed as an upgrade, there’s no sign, no reworking of the intake manifold or linkage or fuel supply, no place where a bracket seems to have been removed or relocated.

Oh, yeah. This motorcycle was ridden. It did its job. Lattin says that while he was doing the research on the parts, it was obvious that the muffler needed to be replaced because it had been cycled through countless periods of heat, as in the engine was running, and cold, when the engine was off. The cylinder bore, the valves and the piston were used up rather than rusted out. And the bearing races were worn, as they’d be if the wheels had turned mile after mile. How the Miller got to that gas station in rural Maine is still a mystery, but whoever got hold of this Miller rode it.

Back to the puzzle. If Harry Miller made this motorcycle in 1902 or ’03, why did he use out-of-date cast iron for the cases and not bother with some sort of free-engine device? And why would a prototype or testbed or demonstrator built by a man in business in San Francisco be labelled as a Wisconsin product?

Equally, when Mrs. Miller said Harry put an engine in a bicycle, did she mean he built a bicycle around an engine? Or (more likely) did the difference not concern her? And how’d that 1901 carb get on an 1897 engine?

And does it matter?

If all this history, so unlikely and romantic it must be true, will allow one more lucky fact, what we see here is America’s first working motorcycle. If this is, in fact, the second Miller motorcycle-and because Harry Miller guided Ole Evinrude and there’s legend that Ole did the same for Harley and Davidson-this machine is the work of the American motorcycle’s godfather.

Either way and best of all, thanks to sharp eyes, dumb luck and equal amounts of work and enthusiasm, that which was lost, has been found. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

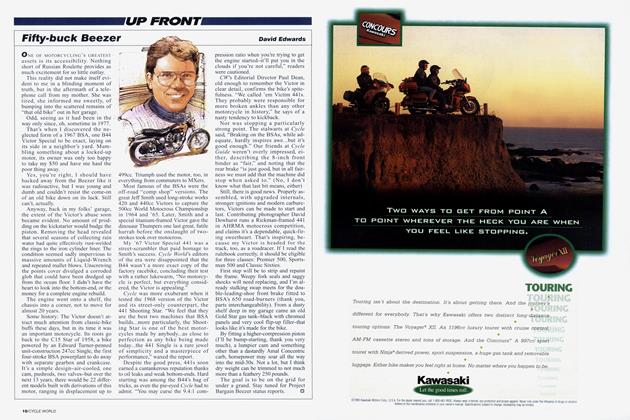

Up FrontFifty-Buck Beezer

March 1996 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOur Brother's Keeper

March 1996 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTorque Shows

March 1996 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1996 -

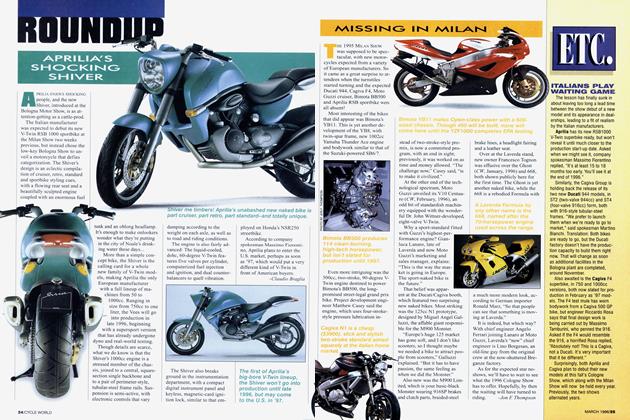

Roundup

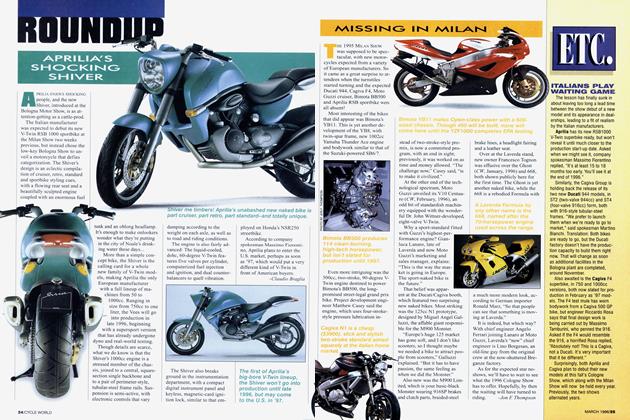

RoundupAprilia's Shocking Shiver

March 1996 By Claudio Braglia -

Roundup

RoundupMissing In Milan

March 1996 By Jon F. Thompson