UPHILL ALL THE WAY

RACE WATCH

Want to race to the top? Bring horsepower.

JON F. THOMPSON

YOU CAN TASTE THE TENSION: The rider, his front wheel aimed dead-on at a near-vertical hillside, hunches his shoulders, twists the throttle to middle revs—and then freezes, for just a few seconds, as he digs deep for that last bit of courage, that last shred of concentration. Then, in a split second, he brings his bike's engine to full rpm and dumps the clutch, lurching forward over the handlebar, hanging on and hoping.

This is the 1989 Invitational Hillclimb Nationals and the rider has just dropped the hammer on a 300-horsepower, nitromethane-fueled racebike pointed up a hill so steep that riders checking the course before the event couldn’t climb it without using their hands.

Riders have gathered here on the premises of the White Rose Motorcycle Club outside York, Pennsylvania, to see who’s the quickest up the hill, to see who’ll take home the most prize money. What they do can be reduced to a few salient numbers: 260 feet of track with a steepness of up to 65 degrees, assaulted by a motorcycle that, with luck, makes enough horsepower to blast up the incline in about six seconds. Simple. But it’s a simplicity which begets an event of ferocious complexity when timing equipment becomes part of the equation.

Hillclimbing, in its professional form, may just be one of racing’s oddest throwbacks. For instance, there’s a refreshing paucity of rules. With the exception of those governing engine size, it’s pretty much RunWhat-You-Brung. Those size classifications are 540 and 800cc, reflecting the maximum engine capacity after 500 and 750cc engines have been overbored. These beasts burn nitro, or maybe alcohol, if that’s the rider’s choice, and they put their power into the ground through huge rear tires—wearing monstrous traction chains—hung on the end of radically lengthened swingarms.

Hillclimb bikes reflect in their variety and construction the sport’s anything-goes attitude. While some riders run modern, high-tech machinery, 25-year-old BSA and Triumph > Twins, which cost about $3000 to build, remain as likely to take a win in either class as heavily modified, fuelinjected, Japanese Fours whose riders have invested upwards of $ 15,000 in their mounts.

No matter what they ride, though, a hillclimber’s skill level and courage are at least as important as his bike’s horsepower production.

Why courage? Because at the Invitational, getting to the top takes much more than merely pinning the throttle, loosing the clutch and training the front wheel towards the clouds. For this is, in effect, a straight-up, motocross-like drag race with no practice runs. The rider, who starts with his bike’s back wheel against a concrete-block wall 10 feet from the hill, sees from his vantage point a racing surface nearly as vertical as the mirror in which he shaves. On launch, the rear tire digs a trench deep enough to lay pipe in, and as the bike howls up the hill, its chassis yaws in vicious arcs around its steering stem as the whirling tire claws for bite, the wide-eyed rider hanging on for dear life.

Just to make things interesting, White Rose club members have built two huge berms, called “breakers,” across the hill, one at about 60 feet and the other at about 200 feet. It ain’t easy.

But, says Louis Gerencer, 58, a Harley-Davidson dealer from Elkhart, Indiana, here with a team of XR750-powered machines for himself and his riders, “It’s fun. Older guys can still do this,” a fact he proves by setting third-fastest time of the day behind two younger competitors.

If Gerencer and his high-powered team have a nemesis, it’s dapper Earl Bowlby, a tidy, gray-haired gentleman who looks as though he’s just stepped out of a Norman Rockwell painting. Bowlby, 55, is a nine-time national hillclimb champion, a man Professional Hillclimbers Association President Conley Newsome calls, “The king of hillclimbers, next to me.”

Incredibly, Bowlby’s championships were won aboard his aging BSA A65 Twin. Though horsepower is important, Bowlby notes there’s more to the hillclimb game than brute force: “You have to be a decent rider and you have to have a little luck on your side,” he says.

In the horsepower department, Bowlby is in a bit of trouble at the Invitational, his spotless Beesa developing 100-plus horsepower on nitromethane, a substance said to double the horsepower developed on gasoline. Other riders claim dyno figures of up to 300 for their Japanese-engined racebikes.

But the trick is getting that horsepower to the ground, and that’s why getting the launch just right is important. Riders want wheelspin because too much hookup brings the front

end off the ground and spoils the launch. And since on this hill the first 60 feet are the most important ones, if the launch is spoiled, the run is spoiled. But you can overdo the launch: Too much power means you get air over the first breaker, and getting air means going slow.

“I been running this hill for 25 years and I still don’t do that first jump right," laments Gerencer.

Indeed, most riders could learn from Earl Bowlby when it comes to technique. His first run this day is very smooth, his take-off perfect, his rear wheel never leaving the ground over the first breaker, and with use of body English that would do a motocrosser proud, he and his bike reach the top in 6.3 seconds, two-tenths of a second behind Gerencer’s first run aboard his hyper Harley. These are the two fast times so far in the 800cc class.

Then the clouds open, wetting the hill. But the deluge doesn’t seem to distract XR750-mounted Tom Reiser of Columbus, Ohio, who cranks off fast time of the day in the rain, a 6.02, to claim the $ lOOO first prize. Bowlby is out of luck as his engine begins to seize at the beginning of his second run. Also out of luck is Bowlby-tutored Tim Frazier, who with his 540cc BSA Twin took a firstin-class here in 1988 but this year can do no better than third, with a 6.89. “The big Multis put out twice as much horsepower as I do,” he explained before his runs. “Fve gotta do a perfect ride, straight as I can get it and keep the rear wheel on the ground. But even this bike comes off

the line so hard and carries so much speed you hardly know the bumps are there.”

But today the power of Frazier’s BSA is not enough; and though old timers give motocross-derived hillclimb bikes little chance, it’s Paul Pinsonnault, from Springfield, Massachussets, with the top time in the 540cc class, posting a 6.72second run aboard a greatly lengthened Honda CR500. His time would have been good enough for sixth place in the 800cc class.

The fans, who’ve sat on the huge lawn in front of the hill to watch the fun, protected by catch nets from the dirt and rocks thrown up by the traction chains, don’t really seem to care who wins. They just came to watch and cheer, happy to be out to observe this most basic of competitions. It may be uphill all the way for the racers, but for the fans, it’s just good fun. And that’s reason enough for watching. Isl

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

November 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

November 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

November 1989 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

November 1989 -

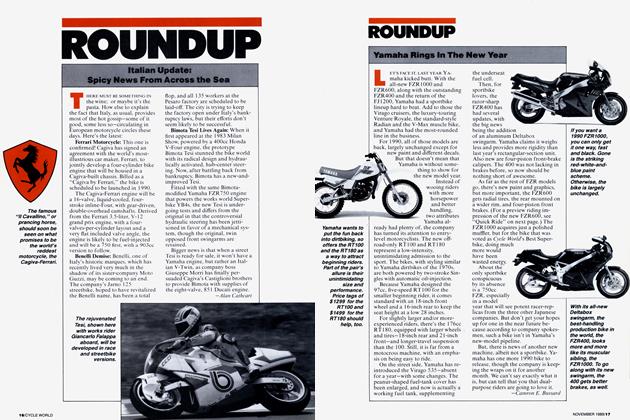

Roundup

RoundupItalian Update: Spicy News From Across the Sea

November 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

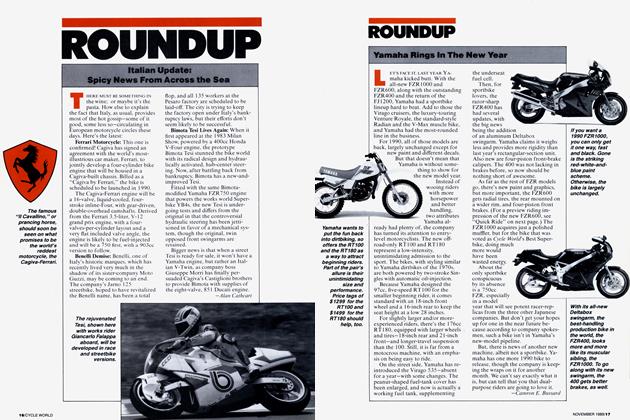

Roundup

RoundupYamaha Rings In the New Year

November 1989 By Camron E. Bussard