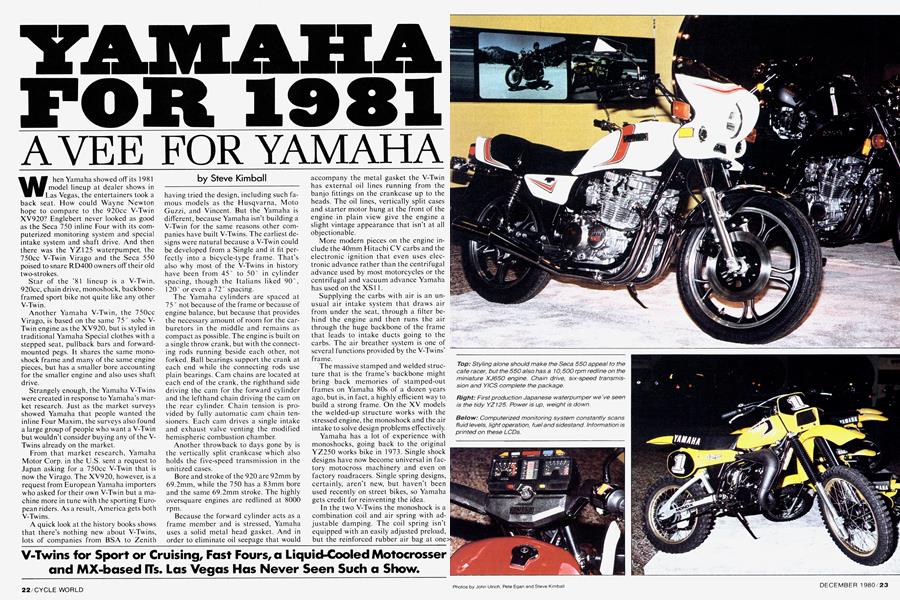

YAMAHA FOR 1981

A VEE FOR YAMAHA

Steve Kimball

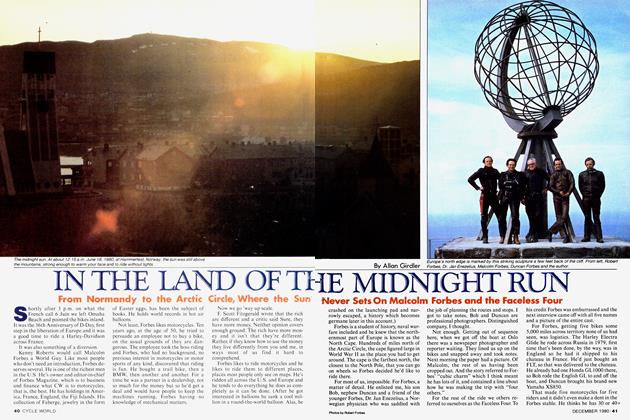

when Yamaha showed off its 1981 model lineup at dealer shows in Las Vegas, the entertainers took a back seat. How could Wayne Newton hope to compare to the 920cc V-Twin XV920? Englebert never looked as good as the Seca 750 inline Four with its computerized monitoring system and special intake system and shaft drive. And then there was the YZ125 waterpumper, the 750cc V-Twin Virago and the Seca 550 poised to snare RD400 owners off their old two-strokes.

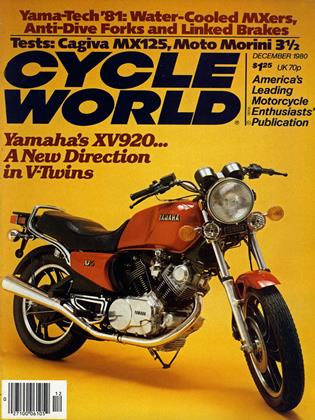

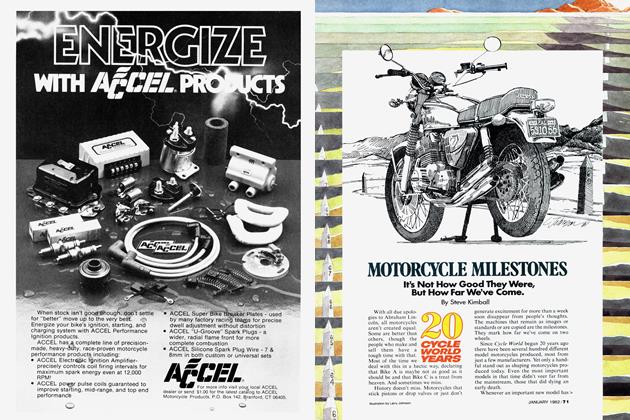

Star of the ’81 lineup is a V-Twin, 920cc, chain drive, monoshock, backboneframed sport bike not quite like any other V-Twin.

Another Yamaha V-Twin, the 750cc Virago, is based on the same 75° sohc VTwin engine as the XV920, but is styled in traditional Yamaha Special clothes with a stepped seat, pullback bars and forwardmounted pegs. It shares the same monoshock frame and many of the same engine pieces, but has a smaller bore accounting for the smaller engine and also uses shaft drive.

Strangely enough, the Yamaha V-Twins were created in response to Yamaha’s market research. Just as the market surveys showed Yamaha that people wanted the inline Four Maxim, the surveys also found a large group of people who want a V-Twin but wouldn’t consider buying any of the VTwins already on the market.

From that market research, Yamaha Motor Corp. in the U.S. sent a request to Japan asking for a 750cc V-Twin that is now the Virago. The XV920, however, is a request from European Yamaha importers who asked for their own V-Twin but a machine more in tune with the sporting European riders. As a result, America gets both V-Twins.

A quick look at the history books shows that there’s nothing new about V-Twins, lots of companies from BSA to Zenith having tried the design, including such famous models as the Husqvarna, Moto Guzzi, and Vincent. But the Yamaha is different, because Yamaha isn’t building a V-Twin for the same reasons other companies have built V-Twins. The earliest designs were natural because a V-Twin could be developed from a Single and it fit perfectly into a bicycle-type frame. That’s also why most of the V-Twins in history have been from 45° to 50° in cylinder spacing, though the Italians liked 90°, 120° or even a 12° spacing.

V-Twins for Sport or Cruising, Fast Fours, a Liquid-Cooled Motocrosser and MX-based ITs. Las Vegas Has Never Seen Such a Show.

The Yamaha cylinders are spaced at 75 ° not because of the frame or because of engine balance, but because that provides the necessary amount of room for the carburetors in the middle and remains as compact as possible. The engine is built on a single throw crank, but with the connecting rods running beside each other, not forked. Ball bearings support the crank at each end while the connecting rods use plain bearings. Cam chains are located at each end of the crank, the righthand side driving the cam for the forward cylinder and the lefthand chain driving the cam on the rear cylinder. Chain tension is provided by fully automatic cam chain tensioners. Each cam drives a single intake and exhaust valve venting the modified hemispheric combustion chamber.

Another throwback to days gone by is the vertically split crankcase which also holds the five-speed transmission in the unitized cases.

Bore and stroke of the 920 are 92mm by 69.2mm, while the 750 has a 83mm bore and the same 69.2mm stroke. The highly oversquare engines are redlined at 8000 rpm.

Because the forward cylinder acts as a frame member and is stressed, Yamaha uses a solid metal head gasket. And in order to eliminate oil seepage that would accompany the metal gasket the V-Twin has external oil lines running from the banjo fittings on the crankcase up to the heads. The oil lines, vertically split cases and starter motor hung at the front of the engine in plain view give the engine a slight vintage appearance that isn’t at all objectionable.

More modern pieces on the engine include the 40mm Hitachi CV carbs and the electronic ignition that even uses electronic advance rather than the centrifugal advance used by most motorcycles or the centrifugal and vacuum advance Yamaha has used on the XS1 1.

Supplying the carbs with air is an unusual air intake system that draws air from under the seat, through a filter behind the engine and then runs the air through the huge backbone of the frame that leads to intake ducts going to the carbs. The air breather system is one of several functions provided by the V-Twins’ frame.

The massive stamped and welded structure that is the frame’s backbone might bring back memories of stamped-out frames on Yamaha 80s of a dozen years ago, but is, in fact, a highly efficient way to build a strong frame. On the XV models the welded-up structure works with the stressed engine, the monoshock and the air intake to solve design problems effectively.

Yamaha has a lot of experience with monoshocks, going back to the original YZ250 works bike in 1973. Single shock designs have now become universal in factory motocross machinery and even on factory roadracers. Single spring designs, certainly, aren’t new, but haven’t been used recently on street bikes, so Yamaha gets credit for reinventing the idea.

In the two V-Twins the monoshock is a combination coil and air spring with adjustable damping. The coil spring isn’t equipped with an easily adjusted preload, but the reinforced rubber air bag at one> end of the suspension unit takes care of suspension stiffness. Pressure range of the air spring goes from a minimum of 7 psi to a maximum of 57 psi, a greater range than is normal for air forks, for instance.

Damping is adjustable to 20 positions. However the remote adjustment knob only provides six adjustment positions. By resetting the remote cable different groups of six adjustments can be provided by the remote adjustment knob, but there is no easy way to have all 20 positions available without moving the cable.

To keep the damping adjustment constant at all temperatures, the damping adjustment is actually controlled by a tapered magnesium rod that screws in or out as the damping knob is turned. Because the magnesium rod expands and contracts with temperature changes, the damping hole becomes smaller at higher temperatures, retaining damping power even when the monoshock heats up with use. The damping control knob and air valve for the air spring are located on the righthand side of the bike below the seat where they are easily accessible.

Neither the 750 nor 920 has a conventional chain drive system. The 750 uses a shaft drive much like that of the XJ650 Maxim, while the 920 has a fully enclosed drive chain running in a grease bath.

At each end of the chain a cast aluminum cover shrouds the sprocket. In between the shrouds are flexible heavy rubber tubes with bellows ends and inner rails molded into the tubes to act as chain guides. The rubber, Yamaha says, is specially formulated to resist wear and work well with the heat and grease that lubricates the non-O-ring 630 chain. Chain adjustment is made by tightening the chain adjusters to a given torque and backing off a prescribed number of turns.

Styling deserves special mention on the pair of Twins. The 750 Virago (do you suppose Yamaha looked the word up in a dictionary?) is typical Yamaha Special. Only on the long, low Virago the clean teardrop tank and pull-back bars and short mufflers and stepped seat seem to fit better than on any of the other Specials. Even sitting on the bike the bars aren’t out of place and a rider isn’t cramped, because the bike suits the style.

On the XV920 the styling isn’t exactly a copy of anything. Some people say the tank looks like a BMW tank because it’s tall and narrow, but then the seat begins crawling up the back of the tank like a caterpiller. The sidecovers had already been changed from an earlier design to the present models with their little air scoops, but the strangest part of the bike is the rear end where the fender mounts to the swing arm and goes up and down with the wheel, like a front fender. Behind the seat there is a small storage box, tail lamp and license plate holder, but there were rumors of more changes occurring to the final 920 before it’s unleashed on the public some time in February.

Next down the excitement scale is the Seca 750 that has about every whiz-bang exciting feature Yamaha or anybody could come up with. At the front there are anti-dive forks linked with the double disc brakes. At the back there’s shaft drive. In the middle is a bigger version of the Maxim’s dohc inline Four, enlarged to 748cc and equipped with a novel secondary intake tract. On top is what Yamaha calls its Computerized Monitoring System (CMS) that consists of liquid crystal displays warning if the oil level, fuel level, battery level, brake fluid level, headlight, tail light or sidestand are posing a problem. All that and it has a refreshing sportstype styling, too.

Beginning with the engine, the 750 has a larger bore and stroke than the 650, 65mm by 56.4mm. Compression ratio stays at 9.2:1 and the carburetors are the same size at 32mm, but the 750 uses Mikuni CV carbs instead of the Hitachi carbs used on the 650. Like the 650 it has the ignition and alternator mounted behind the engine to keep engine width down. And like the 650 the 750 is supposed to be fast, Yamaha people claiming that the Seca is the fastest 750 yet.

An interesting bit of technical magic is the Yamaha Induction Control System (YICS) on the 750 and new 550 Yamaha Fours. Beginning with a little theory, the incoming fuel-air mixture burns best when it’s well mixed and that can be encouraged by high velocities in the intake port and a swirl effect in the combustion chamber. At full throttle the normal intake ports provide good mixture and fill the combustion chamber evenly, but at small throttle openings the velocity falls off and the mixture isn’t evenly distributed through the combustion chamber.

To solve the problem, Yamaha has come up with a system of sub intake ports connected by a manifold. The sub-intake ports are separate from the normal intake ports, but enter the main intake ports just above the intake valve. At small throttle openings each cylinder receives its incoming mixture solely from the sub-inlet port—the main ports being closed by butterfly valves. Because the sub-inlet port is about a quarter as large as the normal intake port, the incoming mixture comes in at great velocity and because the port is angled into the cylinder, the mixture swirls into the cylinder, improving distribution of the mixture. By linking the sub-inlet ports the variation in intake vacuum is reduced.

What all this is designed to do is improve fuel economy 10 percent and increase low and mid-range power. Some Japanese car companies have tried to do the same thing with a third intake valve and two-stage intake manifolds have been designed by several American companies, but the Yamaha system looks like a simpler system than anyone has come up with yet.

A more complicated device on the Seca 750 is the anti-dive front suspension. Like* the anti-dive suspensions used on some road racing machines, pressure on the front brake lever increases compression damping in the fork, keeping the front end from diving and reducing weight transfer during braking. Yamaha’s system has a relief valve in the damping reduction valve that enables the forks to absorb large jolts even when the brakes are applied. And because the front springs don’t have to be strong enough to keep the front end from compressing fully during braking, the springs can be made softer, giving a softer ride.

Air caps are used on the 750’s forks to adjust overall spring rate. The brakes are conventional double discs in front (slotted) and a drum in back. Rear suspension consists of dual adjustable damping shocks on the conventional swing arm.

A third novelty on the 750 Seca is the monitoring system. Between the speedometer and tachometer is a row of LCDs. The top LCD lights up when the sidestand is down, the next if the brake fluid level is low, the next if the oil level is low and the next if the battery level is low. Two others light up if the headlight or tail light don’t work and a final LCD lights if the fuel supply is low. At the bottom of the panel is a four-segment LCD indicating fuel level. With a quarter of a tank left, just one segment lights. If there’s a half tank two light up, three for three-quarters and four if the tank is full. At the top of the panel is a bright red warning light. It flashes if any of the LCDs go on while the motorcycle is in operation. All of the LCDs light up when the motorcycle is first turned on as a check that they work. There’s also a yellow check button that can be pushed to check the system. Finally, there’s a red reset button. If, for instance, the red warning light is flashing on because the fuel supply is low, the rider can push the reset button once and the red light glows continuously. If the reset is pushed twice the red warning light goes out.

The Computerized Monitoring System is integrated into a stylish rectangular instrument pod with the usual lights for signal lights, high beam and neutral and having rectangular-shaped faces for the speedometer and tachometer. The rectangular shapes tie together with the rectangular quartz headlight and rectangular fog light. Yep, there’s two lights on the front of the Seca 750. Other styling touches include moving the brake master cylinder under the gas tank, a la BMW, and having the master cylinder linked to the lever via cable. The 750’s moderately short handlebars are covered in a foam padding, too.

Just as the XJ650 was expanded into the larger 750, the same basic engine design has been used on a pair of smaller bikes, too. There’s the Seca 550 and Maxim 550, the Maxim styled like the> Maxim 650 and the Seca sporting all-new body work that looks like a factory cafe racer Both 550s use the YICS intake system for improved economy and mid-range performance, but should be real screamers with a 10,500 rpm redline on the compact engine.

Engine dimensions are 57 by 51.8mm bore and stroke, 9.5:1 compression ratio and four 28mm Mikuni CV carbs mounted to the dohc inline Four. Unlike the larger XJ Yamahas, the 550s both have chain drive instead of the shaft, and use six-speed transmissions. Suspension is standard forks and swing arms, no adjustable damping or air caps. The Seca 550, however, has a small quarter fairing and additional instruments: a gas gauge and voltmeter. Both are electric start only, use transistorized ignitions, have a single disc front brake and drum rear brake. Weight of the Seca 550 is a claimed 401 lb. dry, making it sound like a potential threat in the 550 roadracing class.

Smallest new Yamaha street bike is the Exciter 1 85, a shrunken version of the successful Exciter I 250cc. The 185, like its big brother gets a stressed engine with counterbalancer shaft, electric start and electronic ignition. The larger Exciter gets a sidestand and this year, making it more convenient for commuters.

It's not a new bike, but the XS1 100 Midnight Special is noteworthy because it gets an integrated brake system for 1981. Similar to the Moto Guzzi system, the Yamaha system operates the left front disc and rear disc when the foot brake is pushed. The hand brake operates the right front disc. What makes Yamaha's system different is a proportioning valve in the pedal-operated brake system. Step lightly on the pedal and both brakes receive the same pressure through the hydraulic system. But push hard on the brake pedal and the proportioning valve reduces rear brake line pressure to keep the rear brake from locking up. Yamaha engineers claim under normal road conditions the rear brake can’t be made to lock because of the proportioning valve.

Other Yamaha street bike notes: the 850 and 1 100 will only be offered as Specials or fully equipped with fairings and saddlebags. There won’t be any standard 850s or 1 100s. There is a new Maxim 650 Midnight Special, dressed in black chrome and gold like the 850 and 1 100 Midnight Specials.

Yamaha’s off-road news for 1 981 can be summed up as a water-cooled 125 motocrosser, motocross-based ITs, improvements to the larger mxers and a new miniminimotocrosser, a 50cc YZinger.

Beginning with the YZ125, the liquidcooled rumor is true. Yamaha thus becomes the first of the major manufacturers to introduce a liquid cooled motocrosser, though the others could be close behind Remember the photos of the works Honda watcrpumper? Well, the YZ125 doesn't look anywhere near as cobby. The small aluminum radiator is mounted in front of the steering head, protected by a grill in the front numberplate. Keeping the bike clean and simple, the frame is used as part of the bike’s plumbing, reducing the number of water lines on the bike. Engine coolant (really a 50-50 mix of water and antifreeze) leaves the radiator and runs through the bottom triple clamp, goes through part of the steering head and down the single downtube of the frame where it enters a short hose that goes to the engine’s high volume water pump. Return water runs up a separate hose and through the steering head, top triple clamp and finally into the tiny radiator.

About the only part of the bike that carries over from 1980 is the carburetor. The forks are new and use larger diameter 38mm stanchion tubes. The reservoir for the monoshock is larger, helping keep the shock fluid cool. The chrome-moly frame is modified to fit the new even smallercased motor and overall weight of the YZ125 is even less this year with the liquid cooled model.

Water cooling is used on the motocrossers to keep power from dropping off as engine temperature rises during long races. According to charts prepared by Yamaha, a normal 1 25 motocrosser only produces about 80 percent of its full power once it warms up. while the liquid-cooled MXer can produce about 90 percent of full power. The objections to liquid cooling have been additional weight, complexity and cost for what should be an inexpensive class of racing. As Yamaha has done it, the liquid cooling has resulted in less weight, little complexity and it may even reduce required maintenance on the engine. As far as cost is concerned, no figures were available, though Yamaha officials expected the 125 to remain less expensive than the air-cooled 250 motocrosser.

Other improvements to the YZ125 are a 1 in. longer swing arm, more monoshock damping adjustments (30 rather than 22), folding gearshift lever, stronger rear wheel spokes, and straight-pull throttle. Suspension travel is 11.8 in. at both ends.

Larger Yamaha motocrossers have gone through minor improvements after being all-new last year. Both the 250 and 465 have lighter frames with improved monoshocks. Damping adjustments on the monoshocks have increased from 22 to 30 positions and the reservoirs have been enlarged to reduce fade. Fork stanchion tube diameter has increased to a whopping 43mm for more precise steering control. Wheel travel is 1 1.8 in. front and 12.2 in. rear.

Other changes for 1981 250 and 465 motocrossers include a folding OW-type shift pedal, straight-pull throttle, improved clutch, redesigned air filter and larger rear brakes.

Beyond the details, the YZ250 has a new intake system it shares with the IT250. Called Yamaha Energy Induction System ( YE1S), it consists of a small plastic canister linked to the intake tube by a rubber hose. That’s all. No moving parts and less than a pound of weight. What these simple pieces do is relieve the intake pulsing at low engine speeds that reduces torque and interferes with clean jetting. Yamaha claims that flow' through carburetor pulses back and forth at low engine speeds as the reed valve opens and closes and this causes the drop in torque and power at certain low engine speeds. The chamber added to the intake tract absorbs the incoming mixture when the reed valve is closed and then dispenses its mixture back to the intake tract when the reed valve is open, improving flow through the carburetor at low and medium speeds. Besides improving power, Yamaha said the YEIS improves fuel economy, too. The system was tried on the smaller bikes but wasn’t as effective as it was on the 250s.

A new semi-motocrosser Yamaha will introduce for 1981 is the YZinger, a motocross-styled kiddie bike with a restricted 49cc two-stroke engine, shaft drive and a 19.1 in. seat height. It has telescopic forks in front, dual shocks in back, three-spoked stamped wheels, automatic clutch and a removable engine speed limiter.

More competition oriented are the new ITs, now painted a bright white instead of the old IT’s blue. Last year the IT1 75 was based on the YZ1 25 motocrosser and this year the IT250 and IT465 are also sharing the motocross frames and engines. They aren’t, however, motocrossers with lights. Though they have the 30-position damping adjustments on the remote reservoir monoshocks, just like the YZ250 and YZ465, the wheel travel is shorter for the IT’s; 10.6 in. at both ends of the IT250, 10.6 in. in front for the 465 and 1 1.0 in. at the rear of the 465. Also, the forks use 38mm stanchion tubes, rather than the larger 43mm units of the motocrossers. Engine size is the same on the MXers and ITs, but the IT250 uses a six-speed gearbox and smaller 36mm Mikuni carb, while the YZ250 has a five-speed and 38mm carb like the 465s. Both have a 3.4 gal. gas tank, straight-pull throttle and aluminum swing arm.