In Search of the Cowbell

Or, A Million Beavers Certainly Can Be Wrong

Steve Kimball

An hour after chasing Ron out the starting gate at the 54th Annual Jack Pine Enduro I knew what I would be doing for the next eight or nine hours.

Eating trees.

That is not what we expected. Both Ron Griewe and I, being California motorcyclists, knew what Eastern enduros would be like. Eastern, meaning on the other side of the desert. We expected mud and creek crossings and logs across the trail. We expected humid weather and man-eating mosquitos. We also expected to do well because we knew what it would be like and we were prepared.

Instead, we ate trees. Lots of trees. All flavors of trees. We ate trees on the left side of the trail and trees on the right side of the trail and trees above the trail. We

ate trees, not because we wanted to or needed to. We ate trees like a drowning sailor drinks sea water, because he gets so tired he can’t keep his mouth closed tight enough to keep it out. We were swimming, no, we were drowning in trees.

These trees were hardly big enough to be called trees, actually. Like anything owned by the last entrant in a liar’s contest, like how fast I went around Kissyourassgoodbye Corner, and like anything from Texas, California trees are somewhat larger than Michigan trees. I mean, we drive full-size cars through the cracks in the base of our redwood trees and in Michigan you just run right over some poor sapling.

But just as 30 trillion Chinese can scare the socks off much bigger and better armed Russians, 30 trillion wimpy little

trees can do a real number on a rider. Perhaps each one of those little bushes wasn’t planted in an exact spot just to trap an innocent motorcyclist, but there is no evidence to the contrary. Cut your handlebars down to 30 in., we were told. What we weren’t told is that the trees are carefully planted 28 in. apart.

What enabled us to survive the first hour was the good fortune of having a late starting number. That, itself, takes a bit of getting used to. Enduros elsewhere are most easily run if no one is ahead of you to slow you down in the rough sections. The guys at the end get to plow through mud holes and muddy creeks churned into 80w contact cement by the first couple of hundred riders. That, we were told, wouldn’t be a problem at the Jack Pine.

Lucky riders get to start an hour or so after the first riders begin sacrificing their bodies to the war effort. Low number guys charge the wall of green flesh without so much as a wallaboreebee, clearing the path. Starting on the 61st minute, with numbers 361 and 461, saved some pain. But not, ouch, enough.

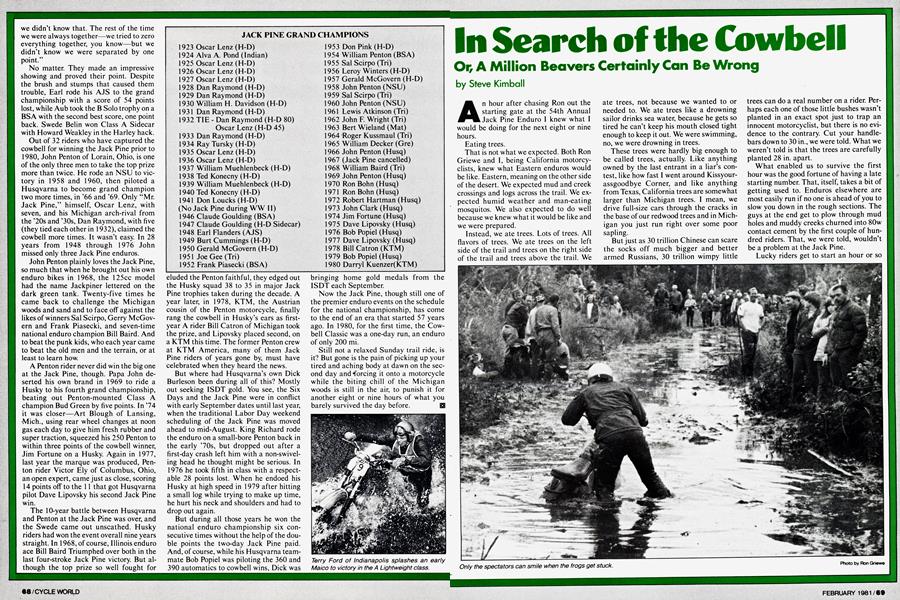

Ron Gnewe

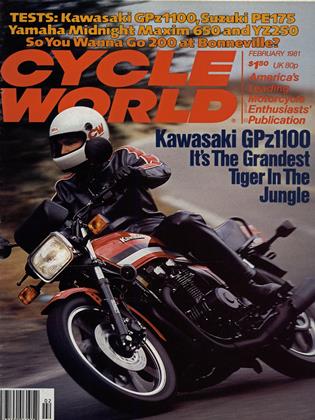

Only the spectators can smile when the frogs get stuck.

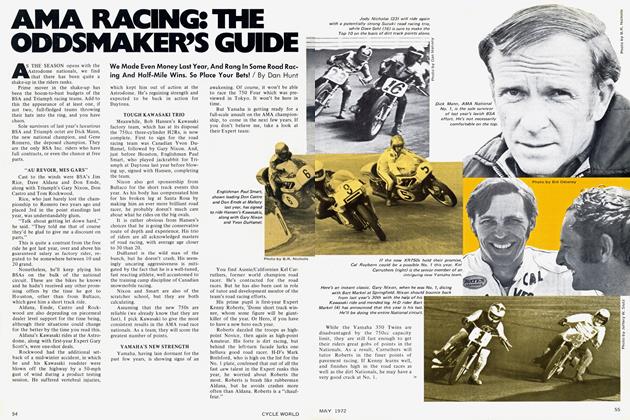

Bob Popiel takes his second Jack Pine championship on the Husqvarna 390 automatic.

Occasionally in the 200 mi. of twisting trail there are what the natives call twotracks. Being sandy roads, these are wonderful for catching up on time and feeling the numbing pain all over your body.

Half-way through the route there’s a lunch stop. Only that time was necessary to catch up with my minute, which I hadn't seen since beginning the enduro. A short section half way through the run was on a paved county road, where sheriffs deputies were checking all the riders for driver’s license and registration. All the bikes entered had to be licensed, but I didn't think of carrying a driver's license along and couldn't use the straight road to catch up. Instead I had to ride beside the pavement on a trail, after losing 10 min. talking with the deputy.

A lot of rumored obstacles weren't in the last Jack Pine, and others were no longer major problems with modern motorcycles.

Those old-time photos showing sidecars being winched through the Rifle River are all history. The state conservation agency won’t allow the enduro to run through any water, so the motorcycle clubs have to build log bridges over creeks and rivers that used to slow the riders down. That famous Jack Pine sand was actually the least of our problems. In the forests it’s a loamy kind of sand that’s a wonderful riding surface until it turns to whoops. Even the loose sand and a few sand hills weren’t noticeably different from blow sand in the California desert. But what I missed most were hills. By mountain state standards, there weren’t any. Riders in California can tell you the time they stopped half way up a mountain to help a Big Horn Sheep with a bloody nose, or how they look down at airplanes on trans-continental flights from some mountaintops. Only in Michigan the sand can’t be stacked up into a steep mountain, so the only elevation changes are little sand hills the course runs over. And the only thing that Ron and I do better than climb hills is talk about how good we are climbing hills.

This doesn’t mean that the Jack Pine is easy, even though there are riders capable of burning some checks. What it means is that the Jack Pine tested and required skills that we hadn’t developed riding in the mountains and deserts of California. We didn’t need to be able to cross 4-ft. deep creeks or climb mountains that Spyderman can’t climb. What is needed for the Jack Pine is experience in dense trees.

Riding between the trees of northern Michigan requires its own special technique. It’s a technique that can’t be learned elsewhere, which is one reason the Jack Pine has been such a challenging course for riders outside Michigan. The technique enables a motorcycle with 30 in. wide handlebars to zip between trees only 28 in. apart. And if everyone timmed the handlebars down to 28 in. the trees would be 26 in. apart. That’s the way the Jack Pine works.

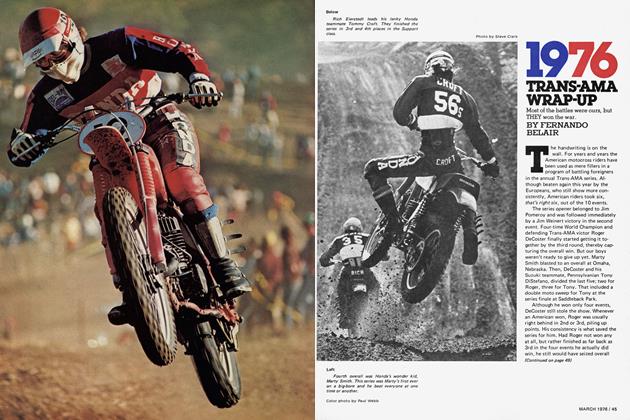

And some of our troubles, we brought with us. Literally. Back home on the wide open spaces Ron has few equals. He’s an A-class desert and enduro man there and he rides the perfect machine for highspeed events; an enduro-ized Yamaha YZ465. Geared up for more speed, if you can believe that.

We’d been told about the woods but we’ve got woods in our mountains. Ron went out and practiced. Cut the bars down, he thought, and while the YZ might weigh more than a smaller enduro bike, surely the extra power would make it all worth while.

Nor were we discouraged when the experienced woodsmen asked what the big yellow bike was. A YZ465, huh? Read about them in the magazines, these guys said, but nobody had ever tried to run between trees at speed with that high and heavy a mount. We’ll find out, we decided, and anyway, we hauled the YZ this far, so we’ll run what we brung.

My Can-Am 250 Qualifier was suited to the woods, and I wouldn’t have minded maybe a 175. Ron wasn’t so lucky. When I rode into the first gas check I felt like a 10pin in a bowling alley. Ron was lying beside his bike. He looked worse than I felt and he felt worse than he looked.

He’d been mugged by gangs of vicious trees. The YZ took to the Jack Pine like a size 12 foot takes to a size nine boot. Ron wasn’t used to not keeping pace so he rode with the experienced, crashed hard, got up and caught up, crashed harder. The only part of his body that didn’t ache was his right arm. It had gone numb. He decided, wisely, that as soon as he could get up he’d find a nice road and ride back to the starting area, keeping as far from the trees as he possibly could.

After the first gas stop the course got tougher. The whoops, at least for a high number rider, were worse. The whoops were steeper and higher than the hills, or what passed for hills.

continued oii page 157

continued from page 70

Of course the trail that leads into the woods from the Lansing Motorcycle Club’s starting area is plenty wide. And Jack Pine veterans have explained that the first check will come after some wide open two-track, so we didn’t take advantage of the relatively wide trail at the beginning of the course and get ahead. And because the trails gradually narrow, there’s a false hope that your motorcycle will fit between the trees, because, after all, you’ve been threading the machine between trees that look too close together, yet aren’t. But at some point half way to the first gas stop there are two trees just a little closer together than your handlebars are wide. You can either hit the tree on the left or the tree on the right or you can get lucky and hit both trees at the same time and have the brake and clutch levers pinch off your fingers before you fly over the handlebars and crash into a third tree.

This is where the Michigan riders clean up because they know the secret to riding between the trees. It’s not a secret you can learn from another rider or read about. And even if I told you the secret, you couldn’t learn it without riding at least a hundred miles through the Michigan trees. That’s because the Jack Pine is the traditional school of hard knocks and there’s a time and a place in the event at which a rider can learn how to ride through the trees. But first one must crash into trees and fall down and become exhausted and then ride some more. By the first gas stop I hadn’t learned it. By the second I wondered if there was a secret. By the third stop I knew other riders had the secret and by the finish I had seen the secret and had even practiced it.

It involves a quick twitch of the handlebars so the front end slides and the handlebars are turned so that the distance across the bars is reduced.

Of course by the time I had the technique figured out the stumps and trees were moving in front of me and I kept hearing riders behind me yell at me to move over. Only when I moved over, no one was there.

At the finish of the Jack Pine I felt strangely triumphant, even though I finished about an hour late, nowhere near the top of my class. The Jack Pine wasn’t over yet, though. That night I continually dreamt of crashing into trees and having the edges of my mouth raked open with a branch across the trail. And I kept hearing the voices. I still hear the voices occasionally.

They’re telling me to go back and run the Jack Pine again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue