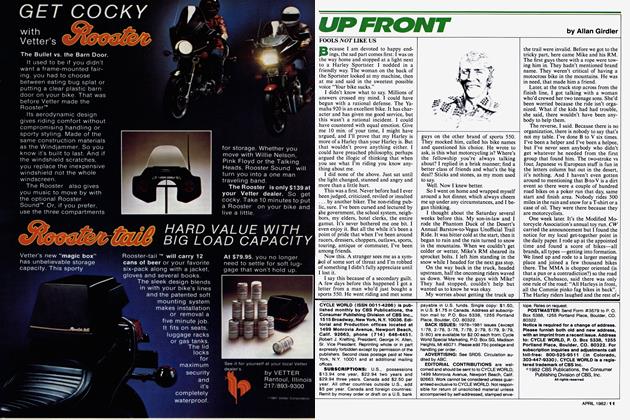

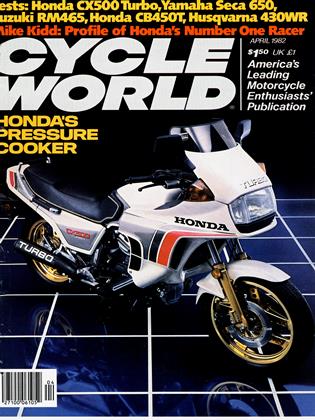

Mike Kidd

PROFILE

Proving That Nice Guys With a Good Program Can Finish First

Steve Kimball

"Show me a hero," said F. Scott Fitzgerald, "and I'll write you a tragedy." Most any writer would agree that it’s easier to create a hero if the subject has tackled great odds and ultimately failed because that just exaggerates the magnitude of the challenge. Maybe that’s why so little has been written about Mike Kidd, current AMA No. 1 plate holder, over the past 10 years of his professional racing career.

Kidd’s lack of notoriety is also due to his competition. Ten years ago Kidd became a rookie expert in the AMA’s Class C racing. Two other rookies that year were Kenny Roberts and Gary Scott. Even the previous year, when all three were junior riders, there was an extraordinary interest in this supposed duel between Scott and Roberts. Dick Mann had the Number One plate when Roberts and Scott and Kidd made Expert and there was some discussion on the circuit that Roberts or Scott might become the national champion in their rookie year.

It was easy to consider Roberts an instant threat, what with his Yamaha sponsorship. He didn’t look bad on a roadracer, either, and road racing was an important part of winning the Number One plate at that time.

Even if Scott hadn’t shown such enormous talent as a rider, it would have been easy to consider him a threat due to the intensity of his personality. He had made a name for himself on Southern California flat tracks where, without immediate factory support, he came up with good machines. And there was always that ferocious intensity from within.

Mike Kidd fit into this fast crowd as he would have fit into any year’s collection of fast new racers: He was fast enough to compete on even terms, but he didn’t start out in California at Ascot. After winning championships in quarter-midgets he began riding motorcycles in all kinds of competition, but he did it in Texas, usually at Ross Downs where his father was a race promoter. His location saw to it that he wasn’t compared with Roberts and Scott all the time, as those other two racers in the Class of ’72 were always compared. But his personality had even more to do with it.

rIt was impossible to meet Mike Kidd and imagine him competing head-to-head in one of the toughest and most daring

speed contests ever created. He was just too pleasant, too personable. Somehow skillful riding wasn’t expected from someone that nice. He should have been selling greeting cards or delivering singing telegrams or anything that nice, normal young men do.

In many ways Kidd has fooled observers of professional racing. Often his strengths have been hidden by other strengths. Because of his early short track racing experience, he was called a short track specialist when he began his Class C expert career. Yet he has still to win his first expert short track.

Kidd has also acquired a reputation as a promoter, a reputation earned as much by his U.S. Army sponsorship as anything else. Many of Kidd’s contemporaries spurn promoting themselves or the sport, feeling a racer should speak on the track with performance. In Kidd’s case, promoting himself, his sponsors and the Winston Pro circuit are all part of being a racer, a part that he enjoys. He has always been around race promotion, with his father promoting the races at his local track in Texas, so putting together a promotional

package about his racing has come easy to Mike and it resulted in the Army sponsorship two seasons ago. Surprisingly, for his abilities as a promoter, Kidd hasn’t raced for any factory team until this year’s ride for Honda. The closest he has come to a factory ride was a contract with Triumph in ’74 that was cancelled when Kidd was injured in a crash at the Santa Fe short track.

Crashing is also one of those secret parts of Mike Kidd’s racing life, one of those areas in which the common knowledge and the facts don’t mesh. Class C racing is rough and dangerous and the racers do get hurt. Mike has been broken by the track more than most, though. That accident in 1974 put him out for most of a season while several broken bones in his left leg healed. Before his first race after that accident he broke that leg again.

Last year, the year he won the national championship, Mike called his wife from the hospital three times after race crashes broke more bones. What doesn’t fit is the personality, which is a common theme with Mike Kidd.

Riders who crash are supposed to be> wild and crazy guys. Dave Aldana was called Rubber Ball because his wild riding, along with his wild way of doing just about anything a person can do, meant he spent a lot of time bouncing. Yvon DuHamel’s crashes on the old Kawasaki roadracers were almost legend. Photographers knew exactly where to stand at particular racetracks to watch him unload, just as he had done before. People who crash seem to be riding out of control or just over their heads. And no one has ever thought of Mike Kidd being out of control.

That may be the underlying strength of Kidd, that he is more in control of himself and his situation than the competition and why, in a season intended for development of the Yamaha flat tracker and sidetracked by injuries, Mike was able to win the national championship. He did it because he was in control.

For the last 10 years Kidd has been learning control and racing. He’s learned how to read his competition and he’s learned the tracks so that he knows how to race everyone on the circuit on each of the tracks. He’s also learned the importance of a “program.” A program is the truck that hauls your bikes to the races, the mechanic who sets up the bikes and keeps them together, it’s the money that can buy a set of intermediate tires at the end of the season or can afford a spare engine or a spare bike. A program is also what Mike hasn’t had during most of his racing career. When those other rookies from the Class of ’72 were on factory teams, Kidd was riding a Triumph or a Bultaco or a Harley that someone would loan him. But it wasn’t until he signed up the Army that he really had a program. It was better last year on the Roberts/Lawwill racing team,

anything a factory effort.

Last year was a freak for the Winston Pro Series with the Number One plate being won with a Harley-Davidson for a team sponsored by Yamaha. Before the season was over some people on the circuit were wearing bright orange T-shirts saying: “Harley-Davidson, the Number One Choice of the Yamaha Racing Team.” It wasn’t supposed to work out that way, but Mert Lawwill’s old Harley race bike was too fast, Kidd won too many points early on and the Yamaha support kept things far enough afloat for things to fall together.

Not even the Number One plate could keep things together.

Having won the championship, Kidd was out of a ride. Yamaha wanted more results for its effort and has enough money to support one rider on the circuit this year. Rookie of the year Jim Filice got that ride because Yamaha believes he will be more useful for a longer period of time. Filice is expected to be the successor to Kenny Roberts on the world road racing scene somewhere down the road and the WPS makes for a good prep school.

In typical Mike Kidd style this became an opportunity, not a loss. The opportunity came from Honda.

Honda did not have a good year on the WPS last year. Before the first flag dropped Honda appeared to have as good a shot at the title as anyone. Honda had Freddie Spencer, good short track machinery, proven TT winners and newly developed machines for the half-miles and miles, plus the benefit of competitive road racing equipment for a rider with road racing talent. None of it quite worked. Freddie always looked like he was trying.

but the dirt tracks were not kind to Hondas.

To anyone who watched Honda’s CX500-based miler follow the pack in any of its heat races last year, the magnitude of Kidd’s opportunity may be questionable. Yet Kidd is optimistic about his chances to retain the crown. He believes Honda is committed to AMA Class C racing, and he thinks that’s good for the sport. He also has a two-year contract with the wealthiest motorcycle racing team, an important consideration to a racer who’s spent 10 years putting together a program.

Near the end of last season Ted Boody raced one of the Honda NS750s at the San Jose Mile. In practice he looked good and fast and in control. In his heat race Boody passed Kidd and was leading the heat when an oil leak put the bike out. At least Honda’s miler could go fast, even if it hadn’t done so all year. In the Junior invitational at San Jose Bill Herndon won the race on another NS750, the first time he had ridden the bike. The potential was there.

Mike Kidd is convinced Honda wants to win the title and can win the title. He has raced and won on Honda’s TT bike. He knows Honda has good short track machines and he believes the mile and halfmile bikes are better than their record. Shortly after signing with Honda he got to ride the NS750. He was surprised to find the ungainly-looking NS750 felt better than he expected. “It feels pretty close,” he said, explaining that the Honda already turns better than the Yamaha flat tracker did. He expects fine tuning of the suspension will result in a winning machine.

Honda’s dirt track effort is being expanded this year. Joining Kidd on the team will be Bill Herndon, the rookie who won that Junior race in San Jose aboard an NS750. Herndon has come from the same background as Kidd, racing at Ross Downs near his home in Dallas. He also has something of the same quiet, likeable personality.

Each rider will have his own mechanic, with Jerry Griffiths becoming the team manager. Griffiths will continue frame development and Jerry Branch will continue engine work. The team will race only the dirt track events, says Kidd, because the time needed to compete in road races would hurt the effort, rather than help it.

Mike knows about road racing. He went to Daytona last year and spent several days practicing with Kenny Roberts on one of Yamaha’s TZ750s. He says he learned a lot from the experience, got so he could tour the course in a competitive time and then he crashed, breaking his back, in practice. His next effort was at Laconia where he again got up to speed quickly, was feeling good and fast, and then had the throttles of his TZ750 stick as he crested a hill at the end of a long straight. Another crash sidelined him for a while longer with another back injury. By the time he came to Laguna Seca the season was well along, he had enough points to be in the hunt for Number One and he wasn’t going to break anything, so he rode around slowly. After the season he said he probably shouldn’t even have been riding at Laguna Seca. This was not the first year Kidd has ever been on a roadracer. His Junior year he had considerable success racing the lightweight machines, winning several races. The decision not to compete in roadraces on the AMA circuit this year is based on the time and effort road races take, nothing else, he says.

Few people picked Mike Kidd to win the championship last year. Most likely would have been Jay Springsteen, or Hank Scott, or Gary Scott, or Randy Goss or maybe Freddie Spencer as an outside pick if the Honda had worked right. Even now, after winning the title, after several years of good finishes and with the biggest name in motorcycling behind him, Mike Kidd is still no better than an even-money pick to repeat.

Whether he can win the title again depends both on the success of the Hondas and on the success of the competition. Harley-Davidson considered dropping out of the Winston Pro circuit but pressure from the dealers forced H-D to continue the team with Jay Springsteen and Randy Goss, probably the strongest team on the circuit. Springsteen is still the most talented rider racing and if his health holds up he would be a likely pick. Goss, the Scott brothers, and Kidd are the next most likely picks, but there are another halfdozen riders easily capable of winning.

On Kidd’s side there is his unquenchable spirit. Some riders lose spirit after injuries and others seem not to be affected. Kidd, if anything, has gone faster after coming back from the hospital. All those years and all those races and all those hundreds of thousands of miles between the races have not slowed Kidd. He is a better racer today and a faster rider now than he was as a rookie. All the ups and all the downs have made him faster, not slower.

How he will respond to this much success can only be answered on the track. Considering the Kidd program, it doesn’t appear that he’s backing off any. Before the season started he was in California testing the Honda NS750, working on all those adjustments needed to make it win. The potential is there, Kidd says, for the NS750 to become superior to the Harleys. The Harleys are, after all, well developed and making as much power as they can and still hold together. There may be more secrets yet to uncover within the XR750, but there aren’t as many left as there once were. The Honda is at the beginning of its development. It has already put out noticeably more power on the dyno than the Harleys and the effort is now in tuning the machine to use the power. By the second half of the season the Hondas should be superior, Kidd says.

Listening to Mike Kidd explain this, it all sounds very real. Kidd doesn’t brag and he doesn’t complain. He knows the other racers are fast and tough, but he doesn’t have a harsh word for any of them. Maybe the Harley guys gave him an intermediate tire for the last race of the season at Ascot and Kidd appreciates that, but he wasn’t out to beat Gary Scott. He was out there to win the championship. Kidd knows his competitors, he knows what they will do on the track and what they will do off the track. Some people on the circuit wanted Kidd to beat Gary Scott for the title because they didn’t want Scott to win. Kidd doesn’t have any problems with Scott, saying that he’s never been surprised by Gary. The things Scott has done that make him unpopular with the Harley team, for instance, haven’t affected Kidd or surprised him and as a result he has no quarrel with Scott or the Harley team or anyone else.

How Mike Kidd gets along with everybody he works with or meets cannot be simply explained. The normal approach is to say he is such a nice guy, but that’s far too simplistic to explain Kidd. Nice guys, everybody knows, finish last and Kidd definitely doesn’t finish last. Certainly he does not have an abrasive personality and he is considerate and very much a gentleman. Mike’s personality goes beyond this lack of offense, though. There is a quiet charisma to him that isn’t expected from someone who can ride a motorcycle that hard. It may not come through a PA system well, but one-to-one there is a genuine friendliness that makes people who have met him, like him.

continued on page 170

continued from page 81

By now Kidd is clearly a veteran of the AMA wars. How much longer he can keep on with this level of racing even he doesn’t know. Although he thinks about working in promotion or public relations for motorcycle racing in three or four years, he says that three or four years ago he would have expected to be through racing by now. Obviously it is still fun, especially with the Number One plate on the front of his motorcycle this year.

What’s the most fun race of the year? Indianapolis mile. That’s one of three races Kidd says will be special this year. The first is Houston, where both the short track and TT will be held. It’s the closest track to Kidd’s home on the outskirts of Dallas, the closest thing to a home track to Kidd. It also kicks off the season. Indianapolis is right in the middle of the season, it’s in the middle of the country and it’s in the middle of Kidd’s plans for the season. It’s also a cushion track, the kind of mile track Kidd has been particularly successful on. Better still, there will be three races held at Indianapolis’ mile.

One key to Kidd’s season will be the second half. That’s when some of the privateers may be running out of money and effort and when the Honda program should be of most importance. Kidd also expects the first half of the season to involve considerable adjustment on the bikes. After that he expects the Honda milers and half milers to be more than competitive. It’s a large if, but it’s easy to believe Kidd.

Those mile and half-mile tracks will be the second key, particularly with the last six races being either miles or halfmiles. The way the championship has been going the last several years, Kidd expects the final races at San Jose and Ascot to decide the season. That’s why he’d like to see those two races switched in the schedule, so more fans could see the final race of the season and so it could be televised. It’s that final mile race at San Jose that Kidd lists as his third important race. If the season is decided before the San Jose mile it will surprise everyone, including Kidd.

How well the NS750 develops will be the last key to the season. This year’s

Winston Pro Series of 26 races includes nine miles and seven half-miles. Without high point finishes in these it will be impossible to retain the Number One plate. There are only two short tracks, four TTs and four roadraces on the schedule, adding enough points for a good allaround rider to benefit.

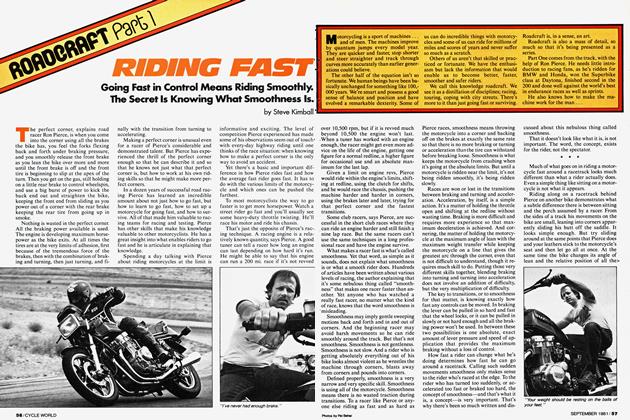

Watching Mike at the last mile race of last year was a good place to see what he is made of. In third place in points for the season, behind Gary Scott and Goss, Kidd had to get points. He had just gotten back in the saddle after being injured at Syracuse. San Jose is a groove track, and drafting is vital to success there. In practice he was doing okay, good enough to make the main in his heat, but not outstanding. In another heat race Randy Goss was black-flagged for an oil leak, putting him out of the points for the race and a long-shot for the title. What Kidd had to do was beat Gary Scott and place well enough to gain points. In the main Kidd didn’t get hooked up with the lead pack at the start of the race and was stuck in the middle of the pack. Any mile demands drafting and San Jose may demand more than most. So Kidd spent half the race scrambling to get away from the pack and trying to catch the draft of the leaders. Every lap he tried another pass, another foot into the turns before backing off, not making up enough distance. It looked as if he wouldn’t catch Gary Scott or gain enough points. To those of us standing on the inside of Turn One, watching every rider slide past barely under control, Kidd’s chances appeared gone.

That’s where all those races and years and the occasional crash come into play.

He has never had a championship to lose, and never lost hope. He didn’t quit at San Jose, either, but kept pressing, until he caught a draft and started flying. It was the last half of the last mile of the season and Kidd never looked better or faster. He was picking off riders every lap, leaving Gary Scott far behind and gaining points as he raced. He didn’t win, not having enough laps to pick off everyone, but he gained enough points with a 3rd place finish to be tied for the lead going into the last race.

The final race at Ascot should have been even more of a thriller, but somehow the finish was almost expected. Goss won but didn’t get enough points, Kidd was ahead of Scott all the way and finished 2nd, winning the championship. Gary Scott was again 2nd for the year with 4th in the race.

Was it the motorcycle, or the tire or the track that made the difference? All, or perhaps none of the above. Maybe, just maybe, it was that indefatigable spirit thaï wouldn’t let Mike lose. 13

View Full Issue

View Full Issue