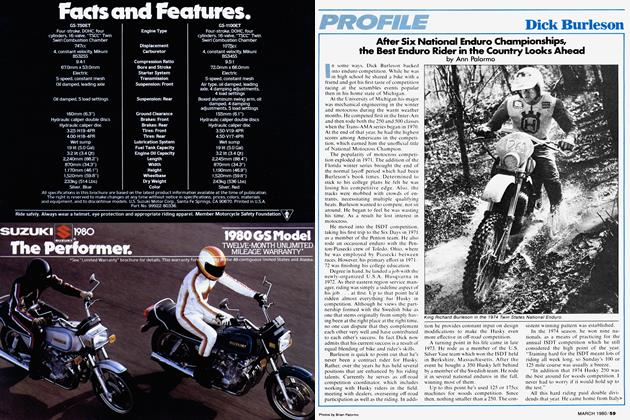

Bert Munro

Senior Citizen of Speed

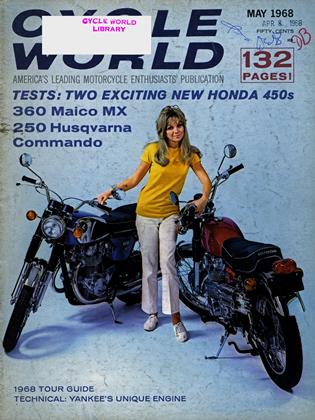

"OH, THAT FOOLISH BOY! When will he stop riding that motorcycle?" Those are mother's words, familiar words to members of the motorcycling fraternity. What makes these phrases unusual in this case is that they were spoken eight years ago of a "foolish boy," then aged 60 years, by his "Mum," whose lifetime spanned a mere 84 summers.

The boy’s foolishness involved leaping from a Velocette road racer when a high speed wobble threatened a severe crash at something over 110 mph.

Bert Munro, now 68 years of age, hasn’t yet stopped riding “that motorcycle.” (Mum now is 92.) At age 12 or 13, Bert drove automobiles in his native New Zealand. But he was 28 before riding his first motorbike in 1915. “Since I got on that motorcycle, I’ve never wanted to be on anything else,” Bert said. Of course, he has been forced by circumstance to operate four-wheeled vehicles — the circumstance his nine excursions from Kiwiland to the glittering salt of Bonneville, Utah, in quest of ultimate speed with an Indian motorcycle nearly as ancient as he.

When Bert talks about speed, his years fall away. Brilliant blue eyes snap and thick-fingered machinist’s hands become animated as Bert draws engine parts in the air. The smile becomes broader. His listeners realize Bert lives for one thing, his single-minded devotion to speed. Dedication is the word that most succinctly describes Bert Munro’s life, a life which is a concerted assault on 200 mph across the North American salt, a hillclimb record in New Zealand, a road race or beach sand mark or, perhaps, a shot at a motorcycle e.t. in quarter-mile drag racing, a sport just now catching on “down under.” Record books are dotted here and there with the name Munro. Ten years ago he garnered the New Zealand under 750-cc speed record and the country’s beach sand open class record as well. And, Bert has grabbed the N. Z. unlimited standing quarter-mile mark at 12.31 seconds, on gasoline, with his 491-cc Velocette.

In 1962, Bert first earned a line of type in the AMA tabulation of Bonneville land speed records. Munro, his streamliner three-finned in those days, with 51 cu. in. established the S-A Class record at 178.971. Bonneville observers said he could have topped this if he hadn’t shut off early by reason of unfamiliarity with the American timing system.

In 1963, Bert’s machine was traveling an estimated 195 mph or more when a connecting rod disintegrated, ending the New Zealander’s hopes for that year.

In 1964, Munro was able to achieve one run and 184.00 mph, fastest of speed week, but could not run for records, prevented from so doing by a combination of wheel bearing failure, poor salt conditions, and excessive wind velocities.

The year 1965 was a 7-week 000.000 year for Bert, but he came back in 1966 with his enlarged displacement engine (56 cu. in.) to establish the S-A-1000 record at 168.066 mph.

Last year, 1967, Bert took another shot at the S-A-1000 mark, this time with the Indian at 58 cu. in., and scored a bull’seye. He qualified at 190.070 at the salt, then pushed his aging Munro Special, with its homemade Indian engine, to a two-way average speed of 183.586 mph, to shatter his previous class record.

All three records were set on straight methanol, without the boost of nitromethane or other additives. Not the special casings of the “experts,” Bert’s tires are simply Dunlop road racing units with the tread ground off. So much for the nitro tippers and the experts.

A summary of his activitiy on American salt includes three records and three fast times. Of those marks, Bert said, “It was something to go home with, now wasn’t it?” His grin assured that it was, indeed, something.

Going home and coming to the U. S. for Speed Week is a matter of 10,400 miles one way. The journey starts in Invercargill, N. Z., the most southerly city in the world, where Bert lives in a stone “shed” with his tools for manufacture of motorcycle parts that seem better suited for the interior of a Swiss watch. Bert must journey almost 1100 miles northward from his almost antarctic home town to his embarkation point. A steamship voyage takes him to Vancouver, British Columbia, then southward to his port of debarkation, Seattle or San Francisco. Each trip has cost Bert $850, more or less ($200 extra if the bike returns to New Zealand), out of his own pocket. Friends in the U. S., some of them members of the completely unofficial “Bert Munro Racing Team,” aid Bert here and there with parts, a place to stay, and a panel truck in which to sleep and to tow his trailered Indian streamliner.

Once, his successes at Bonneville, and his great good humor, earned him “Sportsman of the Year” honors and other awards which amounted to $1400 in cash. “I put it in the bank and used it for my trip the next year,” Bert related.

Sometimes the $850 round trip steamship fare has come hard for Bert, now subsisting on a government pension. Dedication? “Sometimes I’ve gone hungry to get here,” he admitted. “That’s part of the game, isn’t it?” Bert likes a fried chicken dinner as well as anyone else, but his need to satisfy his hungering for speed supersedes his requirements for bodily sustenance. Lodging is a bunk in his machine shop-shed or a steel cot in the rear of his donated 1952 Chevrolet van.

Sometimes the elderly Indian travels to and from New Zealand with Bert. Other times, Bert takes only the engine home with him. If Speed Week is one week, then it follows that Bert spends the other 51 in a given year working on the overage Indian engine. By his own count, he has spent as much as 4000 hours of labor in a year perfecting his LSR powerplant.

Bert bought the Indian new in 1920, and since, has rebuilt it innumerable times.

As a standard machine, the Indian achieved 54 mph in 1926. And, Bert added, “I’ve got it going faster every year since.” From that 54 mph, top speed of the much modified Indian has been raised to near 200 mph. But, Bert complained, “I’ve never had what you would call a good run yet.”

The New Zealand record road strip has been closed to motorcycle speed record attempts by reason of increased automobile traffic. The beach that was used for speed runs is fast disappearing to the tides. “Bonneville is the only place I can run now. But at Bonneville, you can get the long runs. You can get your gears and your line with those long runs. Now, if I could get the perfect run there, I’d never come back.”

He’ll be back, health permitting, because Bert’s dedication is aimed squarely at that round figure of 200 mph. His burning wish is to achieve this mark. “Approximately 200 mph” or guesses won’t do. Bert won’t give up until he has in his cluttered wallet that certified timer’s card with a registered average two-way speed run of the double ton — or more.

Bert’s look became serious, intense. “One day I may do it,” he said, “but I’ve never said I would do it — never in my life.” He doesn’t say he can reach the 200-mph mark, but somehow he creates a firm impression that he will.

Of course, the machine that will take him over the two-ton hurdle is that 1920 Indian Scout that started life as a 596-cc V-twin that now displaces 950-cc.

That V-twin has been converted from side valve to ohv configuration. The single cam was replaced by a four-cam lashup of Bert’s own design. Triple chain drive was installed. Flywheel, pistons, cylinder barrels, connecting rods, cams and cam followers, bushings and lubrication system, all have been replaced again and again — replacement parts hand made with hacksaw, file, lathe and grinder in Bert’s shed shop. Much modified parts that are fitted to the Indian are a 1924 vintage carburetor, a 1933 oil pump, and gears from the year 1916. Bert has built a 17-plate, 1000lb. pressure clutch for the machine. He also has turned the original Indian crankpin down from 0.875 in. to 0.750 in., then sleeved it for a 1-in. total diameter.

The tall, robust New Zealander boomed a laugh. “I’ve put more work in on that bike than I have making a living!”

Bert explained: “Pistons? I make ’em myself.” To cast the alloy billets for his pistons, Bert once used holes in the ground for molds. More sophisticated nowadays, he employs dies he fabricated from a piece of tractor axle steel he found beside a road. For metal, he uses scrapped aluminum pistons — British Ford pistons are his favorite. He melts the scrap pistons down with “a blowlamp (blowtorch), a five-gallon can filled with coke, and a wee iron pot. That’s how I cast my pistons — and I can turn out a pretty fair piston. I try to get the metal as hard as possible.” Bert uses no metallurgical test equipment, just experienced eyeball technique. “I can tell when I have a good piston,” he stated flatly.

When the piston blanks are cast, Bert said, he turns them on his “wee lathe.” The machine is a 20-year-old British-built, 3.5-inch Myford unit. The pistons then are finished on a homemade grinder.

“It used to take me a week to make a piston. Now I can make one in 24 hours,” Bert said. He has made pistons — and other components such as camshafts — for other competitors, but only when parts were not obtainable from other sources. He is always too busy with his old, newly rebuilt Indian to make a practice of supplying parts for others.

His connecting rods, carried half across the Earth in a rawhide suitcase, are literally hand-carved from the high tensile steel of a Caterpillar tractor axle. Bert tempers and hardens these handmade rods to the point of 143-tons tensile strength.

For his battle with the elusive 200 mph mark, Bert brings his jewel-like parts to the U. S., installs them carefully in the extended, expanded, once Indian streamliner frame, then encloses engine and frame within a hand-formed fiberglass shell, sort of a small, wingless, single-seat fighter aircraft with a rudimentary vertical stabilizer at the rear.

Initially, Bert spent five years constructing a streamlined enclosure entirely of aluminum. The handcrafted shell, eight hammered aluminum sections fitted to steel — later aluminum — stringers with self-tapping sheet metal screws, was started in 1955 and completed in 1960. Bert made one speed run in New Zealand with this semi-monocoque aluminum body — and went better than 161 mph. However, he determined that fiberglass would prove both lighter and stronger, thus better suited to his purpose. He took a splash off the aluminum shell, a hand layup process with glass cloth and resin, that required 91 days. This year, before his assault on the salt, Bert built a new shell, again of fiberglass, using the previous glass envelope for a mold.

On-again-off-again retardation parachute regulations caused Bert some wasted time, as he installed a cone housing at the rear for a drogue chute before the ruling was changed, and no parachute brakes were required on two-wheeled equipment at Bonneville. The entire process, including fitting of a lead nose weight and bobbing the tailfin, required 52 days. The new shell carries an air intake forward, Bert said, for better breathing by the driver and better cooling of the engine.

Even with as many years as Bert has behind him in the chase for speed, he becomes nervous in anticipation of a runfor-the-record attempt. “I have enough butterflies in me stomach to start a dairy farm, if they’d give milk,” he grinned. “Once I’m in the run, though, I relax.”

Youthful features, accented by a prominent hook nose, and receding blond hair, only slightly gray at the temples, belie Bert’s 68 years. Grandfather of 21, the 200-mph speed seeker has only one worry. A crash? Certainly not. Bert’s had many of those and survived. He puts his personal fear this way: “One of my grandsons is almost 19 years old, and he’s chasing this little girl fair hot and heavy. What I’m really afraid of is that he’ll get married and have a kid. Then I’d be a great grandfather. And, if they find out I’m a great grandfather, they wouldn’t let me ride, would they?”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

May 1968 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

May 1968 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1968 -

The Scene

May 1968 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Ruin To Record

Ruin To RecordOut of the Rubble of World War Ii Came the Nsu Twin of Wilhelm Herz — the First Motorcycle To Break 200

May 1968 By Richard C. Renstrom -

Fiction

FictionThe Pickup

May 1968 By Robert Ricci