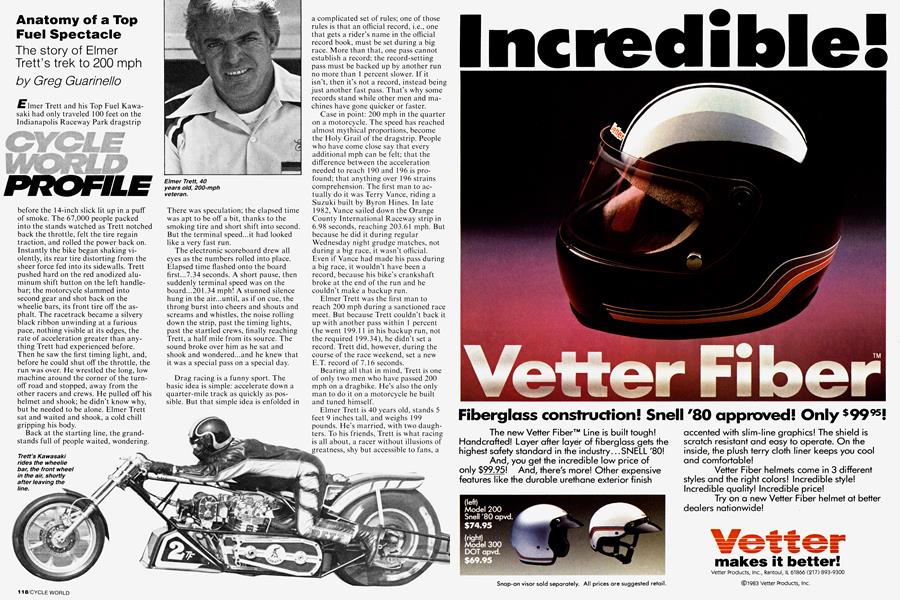

Anatomy of a Top Fuel Spectacle

PROFILE

The story of Elmer Trett’s trek to 200 mph

Greg Guarinello

Elmer Trett and his Top Fuel Kawasaki had only traveled 100 feet on the Indianapolis Raceway Park dragstrip

before the 14-inch slick lit up in a puff of smoke. The 67,000 people packed into the stands watched as Trett notched back the throttle, felt the tire regain traction, and rolled the power back on. Instantly the bike began shaking violently, its rear tire distorting from the sheer force fed into its sidewalls. Trett pushed hard on the red anodized aluminum shift button on the left handlebar; the motorcycle slammed into second gear and shot back on the wheelie bars, its front tire off the asphalt. The racetrack became a silvery black ribbon unwinding at a furious pace, nothing visible at its edges, the rate of acceleration greater than anything Trett had experienced before. Then he saw the first timing light, and, before he could shut off the throttle, the run was over. He wrestled the long, low machine around the corner of the turn-off road and stopped, away from the other racers and crews. He pulled off his helmet and shook; he didn’t know why, but he needed to be alone. Elmer Trett sat and waited and shook, a cold chill gripping his body.

Back at the starting line, the grandstands full of people waited, wondering.

There was speculation; the elapsed time was apt to be off a bit, thanks to the smoking tire and short shift into second. But the terminal speed...it had looked like a very fast run.

The electronic scoreboard drew all eyes as the numbers rolled into place. Elapsed time flashed onto the board first...7.34 seconds. A short pause, then suddenly terminal speed was on the board...201.34 mph! A stunned silence hung in the air...until, as if on cue, the throng burst into cheers and shouts and screams and whistles, the noise rolling down the strip, past the timing lights, past the startled crews, finally reaching Trett, a half mile from its source. The sound broke over him as he sat and shook and wondered...and he knew that it was a special pass on a special day.

Drag racing is a funny sport. The basic idea is simple: accelerate down a quarter-mile track as quickly as possible. But that simple idea is enfolded in a complicated set of rules; one of those rules is that an official record, i.e., one that gets a rider’s name in the official record book, must be set during a big race. More than that, one pass cannot establish a record; the record-setting pass must be backed up by another run no more than 1 percent slower. If it isn’t, then it’s not a record, instead being just another fast pass. That’s why some records stand while other men and machines have gone quicker or faster.

Case in point: 200 mph in the quarter on a motorcycle. The speed has reached almost mythical proportions, become the Holy Grail of the dragstrip. People who have come close say that every additional mph can be felt; that the difference between the acceleration needed to reach 190 and 196 is profound; that anything over 196 strains comprehension. The first man to actually do it was Terry Vance, riding a Suzuki built by Byron Hines. In late 1982, Vance sailed down the Orange County International Raceway strip in 6.98 seconds, reaching 203.61 mph. But because he did it during regular Wednesday night grudge matches, not during a big race, it wasn't official. Even if Vance had made his pass during a big race, it wouldn’t have been a record, because his bike’s crankshaft broke at the end of the run and he couldn’t make a backup run. Elmer Trett was the first man to reach 200 mph during a sanctioned race meet. But because Trett couldn’t back it up with another pass within 1 percent (he went 199.11 in his backup run, not the required 199.34), he didn’t set a record. Trett did, however, during the course of the race weekend, set a new E.T. record of 7.1 6 seconds. Bearing all that in mind, Trett is one of only two men who have passed 200 mph on a dragbike. He’s also the only man to do it on a motorcycle he built and tuned himself.

Elmer Trett is 40 years old, stands 5 feet 9 inches tall, and weighs 199 pounds. He’s married, with two daughters. To his friends, Trett is what racing is all about, a racer without illusions of , shy but accessible to fans, a man who can be taken at face value. For years Trett campaigned Harley-Davidsons, culminating in a double-engined Harley Fueler. His wife Jackie and daughter Gina (now 21 ) worked as his pit crew, helping at the track and assisting with rebuilds and maintenance between races. Kelly, now 9, offered moral support. Long after others gave up running Harleys against the impossiblyquicker Japanese Fuelers, Trett kept the faith, working out of his shop, Trett

Speed and Custom, in Millville, Ohio. A sign painted on the window read, “Harleys Only.”

The time came, though, when Trett couldn’t continue to race and lose on his own. His competition included Vance’s Suzuki-sponsored effort; other racers received parts and contingency money from Yamaha and Kawasaki. Trett occasionally received parts from Harley, but no money, and his bike wasn’t fast enough.

In a last-ditch effort to bring in factory support for a competitive Harley, Trett sent a proposal to Milwaukee. Included was his design for a new engine using Harley-Davidson cylinder heads only (Top Fuel rules require use of stock heads; other parts may be changed.) The barrels were angled at 60° and offset to allow the use of a cutdown Chevrolet 454 crankshaft, each connecting rod having its own throw. The design would eliminate the weakest point of the Harley engine, the forkand-blade connecting rod big ends. The crankcases were to be carved from billet, the pistons and aluminum rods would come from a V-Eight.

The deal didn’t go through and Trett sat out nearly one full season as he pondered what to do. The solution seemed simple, but was a difficult one for Trett, a Harley loyalist who had raced only Harleys, whose business was based on Harleys.

He decided to build and race a Kawasaki.

Not just any Kawasaki, but one built with Trett’s own imprint, like no other. The biggest problem with Top Fuel machines is making them stay together. Broken crankshafts and cases and burnt cylinder heads and melted pistons are standard fare. (Byron Hines refers to pistons as “soldiers” and fills his truck with “armies” before each foray to the racetrack.).

Trett didn’t have the budget to keep his Fueler running on a diet of soldiers; instead, he set out to build a bulletproof engine. He started by buying a set of crankcase molds designed by John Dixon, who abandoned a Top Fuel project to build a jet bike. Trett modified the molds and designed a forged, one-piece, six-main-bearing crankshaft to accept aluminum rods; the crank and the rods came from a company specializing in making parts for fourwheel dragsters. MTC made special pistons for the 1260cc engine.

Trett fitted MTC barrels to the cases, topping them off with a reversed cylinder head. A Magnuson supercharger mounted in front of the head, with a two-speed Funny Car transmission behind the short cases. Karata Enterprises belt drives and motor plates linked all the parts and held them in a frame built by Bonnie Truett. Trett fitted Performance Machine wheels and brakes and headed to a local dragstrip, making pass after pass adjusting and sorting out the new machine. Trett burned more nitromethane testing than he’d normally use in an entire season of racing, but it paid off. In 1982, his first season with the new bike, Trett earned the Number Two plate in all three drag racing organizations: NMRA, IDBA and AMA/Dragbike.

To give it a name, 1983 was The Year of Trett. He entered five NMRA races and won every one. He was named NMRA Professional Rider of the Year. Jackie and Gina were named NMRA > Professional Mechanics of the Year.

The Tretts were named I DBA Family of the Year. He broke no parts, fried no engines, burned no soldiers.

The pass began like any other. Elmer Trett pushed his bike past the fence that isolated a small group of motorcycles from nearly 1000 race cars. He snaked his Kawasaki through a sea of four wheelers and wide-eyed spectators, part of a huge crowd gathered for a Labor Day weekend of racing.

Trett’s machine stood out, the cylinder head reversed, a compact supercharger with an open velocity stack facing forward. The exhaust ran under the seat and curved upward, exiting through the rear fender, just behind the seat. The rear slick measured 14 inches across, so wide that Trett’s bike remained upright without a stand.

Trett strapped on his helmet and pulled on his gloves, and sat on the bike. He reached down and plugged in the remote electric starter, then grabbed the bars as Gina held the starter handles and spun the engine. The dull sound of the engine turning over became a slapping BRAP! BRAP! the instant Trett switched on the ignition, and Gina leapt back with the starter.

Bystanders plugged their ears with their fingers as Trett edged the machine forward, around the puddled water in the burnout area; Gina and Jackie both pushed hard to roll the 720 pounds combined weight of bike and rider back into the water, then stood clear. Trett shifted his weight back, pushed the button to engage second gear, pulled on the throttle and released the brakes, the Kawasaki shooting forward, passing the starting line on a contrail of gray and white smoke, the thundering noise beating against the crowd. Jackie and Gina reappeared and heaved husband and father and machine back to the starting line, all the while looking for loose lines or leaks or problems. Trett punched the transmission into first gear.

He was alone, inching forward, pushing with his legs, staging, first the prestaged light blinking to life, then, slowly, ever so slowly, the staged light glowing. Trett concentrated, unblinking. In the other lane, Bo O’Brochta was overanxious and left early, red-lighting, but Trett didn’t notice. All his energy was focused on the row of lights that controlled his destiny on this pass. He rolled on the throttle when he sensed the yellow light in his lane; as the green shone, Trett was on his way.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue