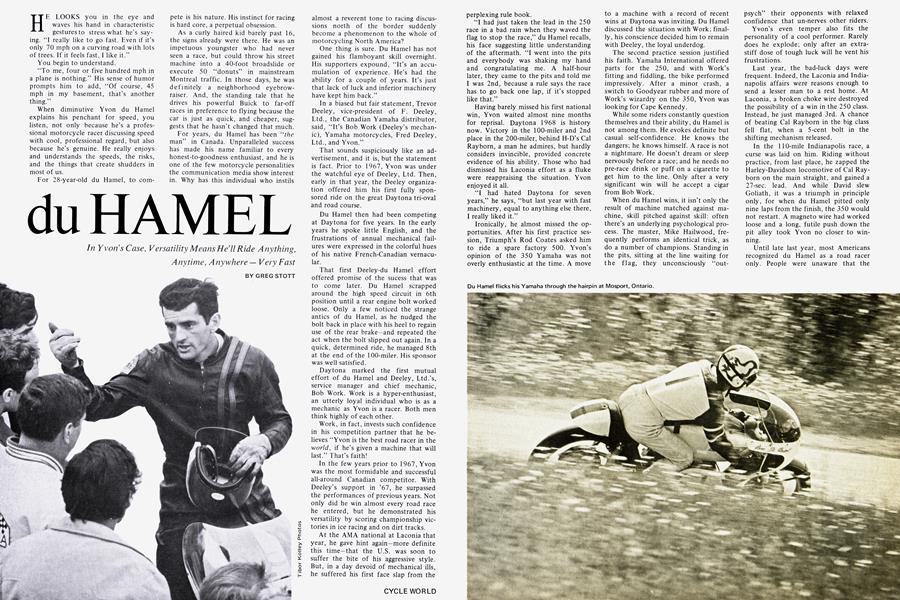

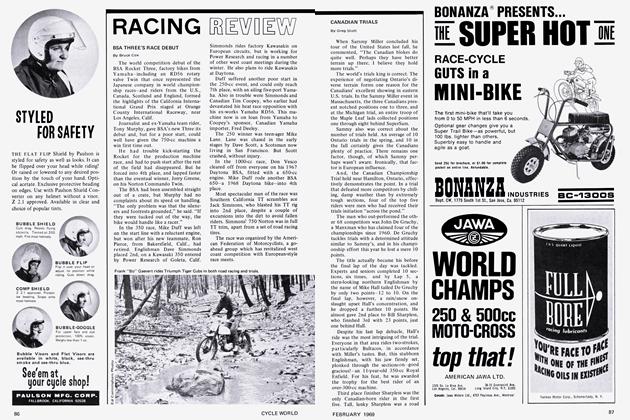

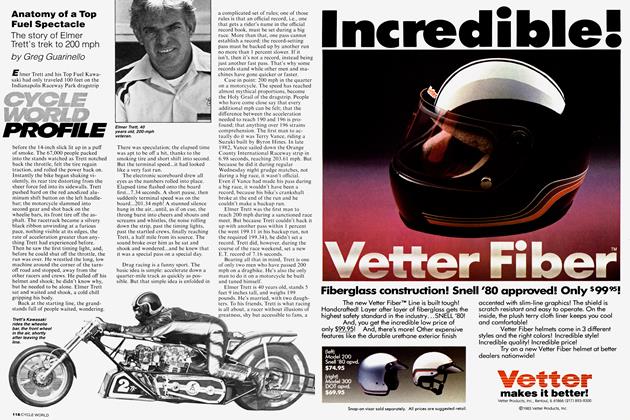

du HAMEL

In Yvon's Case, Versatility Means He'll Ride Anything, Anytime, Anywhere - Very Fast

GREG STOTT

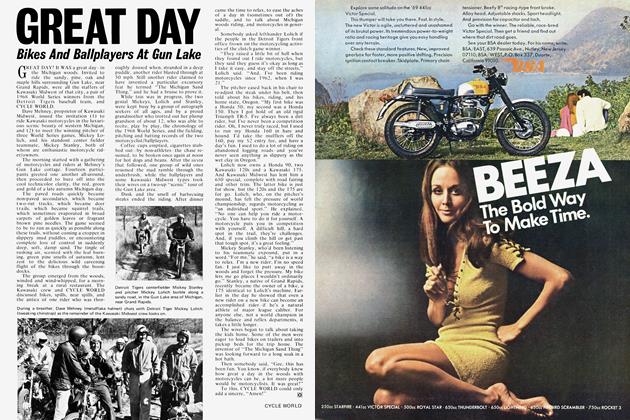

HE LOOKS you in the eye and waves his hand in characteristic gestures to stress what he's saying. "I really like to go fast. Even if it's only 70 mph on a curving road with lots of trees. If it feels fast, I like it."

You begin to understand.

“To me, four or five hundred mph in a plane is nothing.” His sense of humor prompts him to add, “Of course, 45 mph in my basement, that’s another thing.”

When diminutive Yvon du Hamel explains his penchant for speed, you listen, not only because he’s a professional motorcycle racer discussing speed with cool, professional regard, but also because he’s genuine. He really enjoys and understands the speeds, the risks, and the things that create shudders in most of us.

For 28-year-old du Hamel, to com-

pete is his nature. His instinct for racing is hard core, a perpetual obsession.

As a curly haired kid barely past 16, the signs already were there. He was an impetuous youngster who had never seen a race, but could throw his street machine into a 40-foot broadslide or execute 50 “donuts” in mainstream Montreal traffic. In those days, he was definitely a neighborhood eyebrowraiser. And, the standing tale that he drives his powerful Buick to far-off races in preference to flying because the car is just as quick, and cheaper, suggests that he hasn’t changed that much.

For years, du Hamel has been “the man” in Canada. Unparalleled success has made his name familiar to every honest-to-goodness enthusiast, and he is one of the few motorcycle personalities the communication media show interest in. Why has this individual who instils almost a reverent tone to racing discussions north of the border suddenly become a phenomenon to the whole of motorcycling North America?

One thing is sure. Du Hamel has not gained his flamboyant skill overnight. His supporters expound, “It’s an accumulation of experience. He’s had the ability for a couple of years. It’s just that lack of luck and inferior machinery have kept him back.”

In a biased but fair statement, Trevor Deeley, vice-president of F. Deeley, Ltd., the Canadian Yamaha distributor, said, “It’s Bob Work (Deeley’s mechanic), Yamaha motorcycles, Fred Deeley, Ltd., and Yvon.”

That sounds suspiciously like an advertisement, and it is, but the statement is fact. Prior to 1967, Yvon was under the watchful eye of Deeley, Ltd. Then, early in that year, the Deeley organization offered him his first fully sponsored ride on the great Daytona tri-oval and road course.

Du Hamel then had been competing at Daytona for five years. In the early years he spoke little English, and the frustrations of annual mechanical failures were expressed in the colorful hues of his native French-Canadian vernacular.

That first Deeley-du Hamel effort offered promise of the sucess that was to come later. Du Hamel scrapped around the high speed circuit in 6th position until a rear engine bolt worked loose. Only a few noticed the strange antics of du Hamel, as he nudged the bolt back in place with his heel to regain use of the rear brake-and repeated the act when the bolt slipped out again. In a quick, determined ride, he managed 8th at the end of the 100-miler. His sponsor was well satisfied.

Daytona marked the first mutual effort of du Hamel and Deeley, Ltd.’s, service manager and chief mechanic, Bob Work. Work is a hyper-enthusiast, an utterly loyal individual who is as a mechanic as Yvon is a racer. Both men think highly of each other.

Work, in fact, invests such confidence in his competition partner that he believes “Yvon is the best road racer in the world, if he’s given a machine that will last.” That’s faith!

In the few years prior to 1967, Yvon was the most formidable and successful all-around Canadian competitor. With Deeley’s support in ’67, he surpassed the performances of previous years. Not only did he win almost every road race he entered, but he demonstrated his versatility by scoring championship victories in ice racing and on dirt tracks.

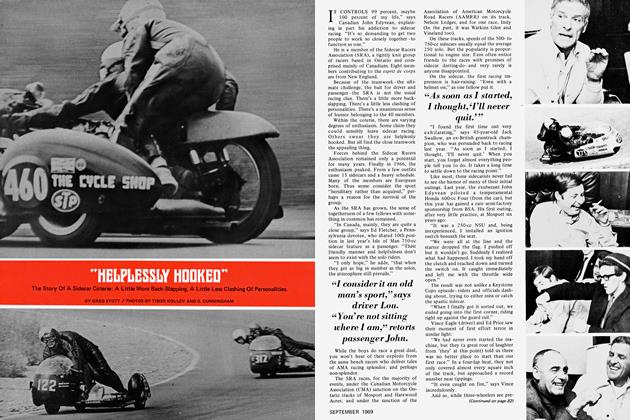

At the AMA national at Laconia that year, he gave hint again-more definite this time—that the U.S. was soon to suffer the bite of his aggressive style. But, in a day devoid of mechanical ills, he suffered his first face slap from the perplexing rule book.

“I had just taken the lead in the 250 race in a bad rain when they waved the flag to stop the race,” du Hamel recalls, his face suggesting little understanding of the aftermath. “I went into the pits and everybody was shaking my hand and congratulating me. A half-hour later, they came to the pits and told me I was 2nd, because a rule says the race has to go back one lap, if it’s stopped like that.”

Having barely missed his first national win, Yvon waited almost nine months for reprisal. Daytona 1968 is history now. Victory in the 100-miler and 2nd place in the 200-miler, behind H-D’s Cal Rayborn, a man he admires, but hardly considers invincible, provided concrete evidence of his ability. Those who had dismissed his Laconia effort as a fluke were reappraising the situation. Yvon enjoyed it all.

“I had hated Daytona for seven years,” he says, “but last year with fast machinery, equal to anything else there, I really liked it.”

Ironically, he almost missed the opportunities. After his first practice session, Triumph’s Rod Coates asked him to ride a spare factory 500. Yvon’s opinion of the 350 Yamaha was not overly enthusiastic at the time. A move to a machine with a record of recent wins at Daytona was inviting. Du Hamel discussed the situation with Work; finally, his conscience decided him to remain with Deeley, the loyal underdog.

The second practice session justified his faith. Yamaha International offered parts for the 250, and with Work’s fitting and fiddling, the bike performed impressively. After a minor crash, a switch to Goodyear rubber and more of Work’s wizardry on the 350, Yvon was looking for Cape Kennedy.

While some riders constantly question themselves and their ability, du Hamel is not among them. He evokes definite but casual self-confidence. He knows the dangers; he knows himself. A race is not a nightmare. He doesn’t dream or sleep nervously before a race; and he needs no pre-race drink or puff on a cigarette to get him to the line. Only after a very significant win will he accept a cigar from Bob Work.

When du Hamel wins, it isn’t only the result of machine matched against machine, skill pitched against skill: often there’s an underlying psychological process. The master, Mike Hailwood, frequently performs an identical trick, as do a number of champions. Standing in the pits, sitting at the line waiting for the flag, they unconsciously “outpsych” their opponents with relaxed confidence that un-nerves other riders.

Yvon’s even temper also fits the personality of a cool performer. Rarely does he explode; only after an extrastiff dose of tough luck will he vent his frustrations.

Last year, the bad-luck days were frequent. Indeed, the Laconia and Indianapolis affairs were reasons enough to send a lesser man to a rest home. At Laconia, a broken choke wire destroyed the possibility of a win in the 250 class. Instead, he just managed 3rd. A chance of beating Cal Rayborn in the big class fell flat, when a 5-cent bolt in the shifting mechanism released.

In the 110-mile Indianapolis race, a curse was laid on him. Riding without practice, from last place, he zapped the Harley-Davidson locomotive of Cal Rayborn on the main straight, and gained a 27-sec. lead. And while David slew Goliath, it was a triumph in principle only, for when du Hamel pitted only nine laps from the finish, the 350 would not restart. A magneto wire had worked loose and a long, futile push down the pit alley took Yvon no closer to winning.

Until late last year, most Americans recognized du Hamel as a road racer only. People were unaware that the Canadian’s background covers almost all popular branches of the sport. Du Hamel, in fact, first met with competition on a dirt track, in 1958.

“I borrowed a helmet from one fellow, a jacket from another, boots from somebody else, and went out and raced.” He finished 2nd. “After my second race a few weeks later. I wanted to quit. My throttle stuck open, and 1 hit another rider and went down hard.”

Three weeks later, however, he was back in competition.

Road racing did not enter his career until 1961, at Ontario’s airport circuit, Harewood Acres.

“I rode a Harley-Davidson to the track, and raced a Gold Star. It was almost stock, but it had clip-ons—something uncommon at that time.” On the BSA, he won every junior race.

One man who helped du Hamel in those years preceding his association with the Deeley setup was George Davis, himself a veteran racer. The relationship between the two men is paternal, rather than that of sponsor and rider. George has used his position with Skoda and Jawa Motors in Canada to arrange many rides for Yvon, but just as often he has gone to his own expense to find machines. Even today, George sees that his “son” has the best CZ scrambles machinery available.

In addition to a string of victories on dirt tracks, in the peculiar sport of ice racing, and in road racing, du Hamel has scored impressively over the rough, winning many scrambles for the Canadian Challenge team. In 1965, he placed 2nd in the Canadian National Championship Trial—in more than two years, his first effort at the art of balance.

“I enjoy scrambling, but you have to be in top physical condition to do well. Sometimes I get out of shape and pay the penalty.” This happened at the Pepperell International Motocross last October, and he admitted to tiring quickly on the rough course.

And that is du Hamel—telling it like it is. No blame falls unnecessarily on the machine, the mechanic, or the course. He knows that No. 1 position isn’t earned by kidding himself.

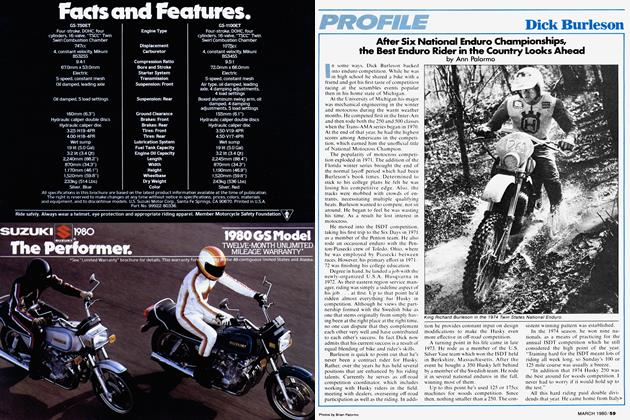

In addition to being champion in all branches of Canadian motorcycling—a goal he barely missed in 1967—Yvon’s ambitions incline toward professional AMA racing. His sense of achievement in Canadian events certainly has dwindled since he joined forces with Yamaha. So, this year, du Hamel will compete on Yamahas on half-mile, mile, TT, and short tracks, and in road racing—in fact in any kind of racing that puts National points up for grabs.

“We’re out to get the No. 1 plate in 1969,” he said frankly, as 1968 came to a close.

His outlook, disconcerting to some, is very necessary and very real. National champion Gary Nixon proved the point in 1967 and 1968. And, since Nixon very likely will wish to emphasize his determination this year, the No. 1 plate will not easily be captured.

With the purpose of studying the riders, machines, and tracks, in readiness for this year, Yvon and Bob Work attended three of the 1968 dirt track races—at Sacramento, Oklahoma, and Ascot. The debut was not earth-shattering, but impressive and a very real omen.

At the great Sacramento mile, Yvon rode so fiercely that fans shook their heads as though Racquel Welch had strolled past. Confusion about dirt track start signals sent him off in last place, but he quickly soared up to 2nd. In the end, he managed 6th place, with an almost-seized rear chain. And that was his first mile race for more than five years.

Both Oklahoma and Ascot were disappointments. The former instilled in Deeley and du Hamel further reluctance to respect rules simply because they are allowed print. After being involved in a crash—through no fault of his own—his battered Yamaha was rushed to the pits for replacement of the front wheel, and repairs to the seat and a fender.

Over the public address system came the announcement, “We are sorry, but Yvon du Hamel will not be able to ride because his machine was fixed in the pits.” After verifying the statement with officials, du Hamel and Work sat in the pits contemplating a rule that, for no obvious reason, deprived a large crowd of seeing a star rider in a race they had paid liberally to attend.

Hopes for a win at Ascot were dashed when the bike seized, for the first time ever.

The disappointments have taught Yvon that, despite his efforts, there are many circumstances beyond his control. Yvon’s sense of humor helps him to accept the bad with the good. His mannerisms, the excitement in his voice and his droll, witty perspective often create audiences for his many humorous racing tales.

One of his nicknames is Super-Frog— Frog being a rather crude tag applied by certain English-speaking Canadians to French Canadians. Typical of his sense of humor was an incident a few years ago when he was asked if he would enjoy the prospect of competing in Europe. “I’d rather be a big Frog in a little pond,” he replied, poker faced, “than a little Frog in a big pond.”

Yvon’s incomplete understanding of the English language also has provided some hilarious times. He began to speak English only six years ago, and uses the language fluently now. But, occasionally, a point of grammar will confuse him. Until recently he asked for “one eggs and bacon” when ordering breakfast.

When Yvon travels, it is, as often as possible, with his wife, Linda. Of Italian descent, she is the woman behind the man. There’s a unique understanding between them. Like the majority of the wives of motorcycle and automobile racers, she worries, but she always gives support. And one can sense that Yvon appreciates this.

Mario, the eldest of their three children, often joins the troop, too. Of the children, he is the reflection of his father. At age 2, he was riding a minibike and now, at 6, he rides a miniaturized Yamaha 80 with cool abandon and skill. The broadslides and donuts papa exhibited at 16, little Mario will learn before he’s 7.

Other than the very tough goal of the AMA No. 1 plate, du Hamel’s plans for the future are flexible. He has been offered rides in racing cars, but motorcycling offers too much for him to leave two wheels. He considers the present 10-year investment of time and money too much to sacrifice.

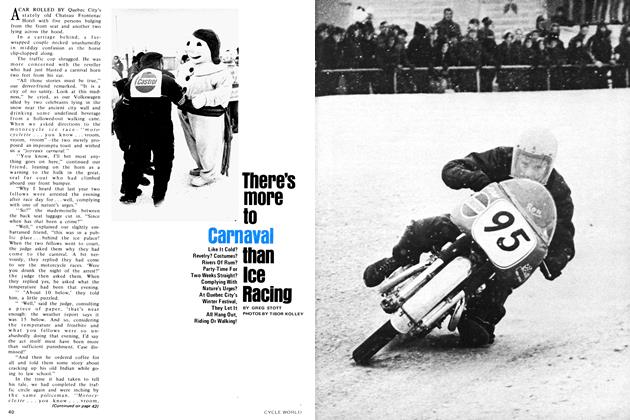

Snowmobile racing provides winter fitness for a number of Quebec’s motorcycle competitors, and this winter Yvon is combining this new sport with ice racing, on bikes, as a conditioner for the coming season.

With his brother, Rehaume, he operates a thriving four-stable service station not far from his home in Montreal, the capital of Canada’s bilingual province, Quebec.

And what about the day when the track game is over? Ask Yvon, and he glances at that understanding wife and says with half a smile, “When racing is over? You mean in 15 or 20 years?” She catches the half smile, but still her face suggests a hint of exasperation. She knows almost anything is possible. She knows Yvon du Hamel is a racer by instinct.