Seeking Pavement Thrills On a Budget

Box Stock Road Racing Delivers High Thrills Per Dollar

John Ulrich

We meet them every time we set up a photo shoot on a winding road. They see the camera, the photographer, the bike, the rider. They're street racers, canyon flyers, kids and not-so-kids with street bikes set up as ersatz road racers, with rearsets and clubman bars and half fairings and everything in between. Some imitate form, but forget function, like the teenager with tucked-in-for-ground-clearance pipes on his RD400, the stock footpeg mounts looping out anyway.

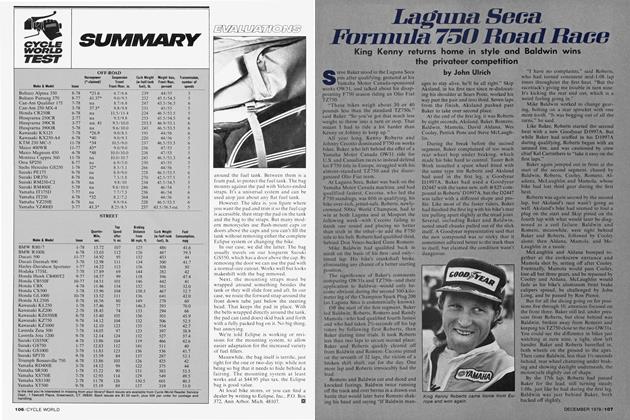

The conversations run the same every time. They tell us about the time they and so-and-so really had a great race down the canyon. We tell them it doesn’t mean a thing, that street racing is 99 percent madness and 1 percent skill and machinery, that the place to really find out how good you are is the racetrack. There are problems. New leather racing suits cost a lot of money. Not everybody has the cash for extensive performance modifications and racing tires. The bike a person owns may not be the motorcycle dominating the applicable class. But there are solutions as well. ABC Leathers (9802 S. Atlantic Ave.. Southgate. Calif. 90280) sells a basic custom-fitted AMA-approved Dupont Cordura nylon road racing suit for $150 (compared to $215 for an unlined ABC leather suit). Luja Enterprises (850 E. San Carlos Ave.. San Carlos, Calif. 94070) retails Cordura suits complete with padding and colored strips for about $150. Many leather repair shops, such as Rister Leather Works (134 Second St., Upland. Calif. 91786) typically sell used leather road racing suits for $35 to $90.

And there are classes for riders who either don’t want to spend—or don't have— the money for hopping up their street bike and fitting wider rims and slicks and double discs and on and on. In California, they call it Box Stock, although the class is actually closer to what organizations in other states call Production. According to the rules used by both the American Federation of Motorcyclists (AFM) and the American Road Racing Association (ARRA). Box Stock racebikes can be fitted with accessory shocks, different handlebars (as long as they use the stock mounts) and any DOT-approved street tires. Gearing changes are allowed. Mirrors. stands and turn signals must be removed and oil drain plugs must be safetywired. No engine modifications are allowed. The stock airbox, air filter and exhaust system must be used. Footpegs may be modified to fold, but must use stock mounts.

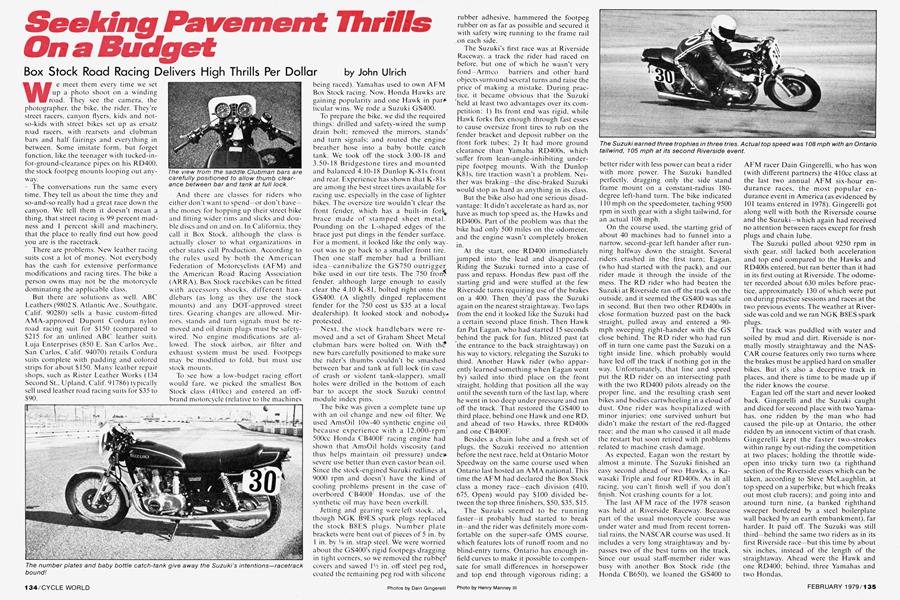

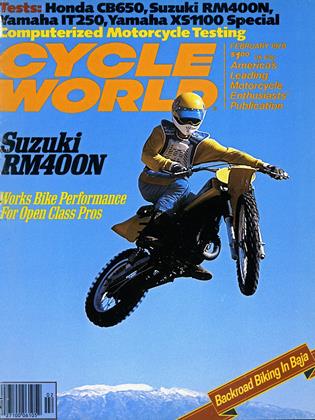

To see how a low-budget racing effort would fare, we picked the smallest Box Stock class (410cc) and entered an offbrand motorcycle (relative to the machines being raced). Yamahas used to own AFM Box Stock racing. Now. Honda Hawks are gaining popularity and one Hawk in par«* ticular wins. We rode a Suzuki GS400. To prepare the bike, we did the required things: drilled and safety-wired the sump drain bolt; removed the mirrors, stands" and turn signals; and routed the engine breather hose into a baby bottle catch tank. We took off’ the stock 3.00-18 and 3.50-18 Bridgestone tires and mounted and balanced 4.10-18 Dunlop K-81s front and rear. Experience has shown that K-81s are among the best street tires available for racing use. especially in the case of lighter bikes. The oversize tire wouldn't clear the front fender, which has a built-in forl^t brace made of stamped sheet metal. Pounding on the L-shaped edges of the brace just put dings in the fender surface. For a moment, it looked like the only wayout was to go back to a smaller front tire. Then one staff member had a brilliant idea—cannibalize the GS750 outrigger bike used in our tire tests. The 750 froni fender, although large enough to easily clear the 4.10 K-81, bolted right onto the GS400. (A slightly dinged replacement fender for the 750 cost us $35 at a local dealership). It looked stock and nobody^* protested.

Next, the stock handlebars were removed and a set of Graham Sheet Metal clubman bars were bolted on. With the new bars carefully positioned to make sure the rider’s thumbs couldn’t be smashed between bar and tank at full lock (in case of crash or violent tank-slapper). small holes were drilled in the bottom of each bar to accept the stock Suzuki control module index pins.

The bike was given a complete tune up with an oil change and new oil filter. We used AmsOil 10w-40 synthetic engine oil because experience with a 12,000-rpm 500cc Honda CB400F racing engine had shown that AmsOil holds viscosity (and thus helps maintain oil pressure) unde» severe use better than even castor bean oil. Since the stock-engined Suzuki redlines at 9000 rpm and doesn't have the kind of cooling problems present in the case of' overbored CB400F Hondas, use of the synthetic oil may have been overkill.

Jetting and gearing were left stock, al% though NGK B9FS spark plugs replaced the stock B8ES plugs. Number plate brackets were bent out of pieces of 5 in. by 1 in. by V» in. strap steel. We were worried about the GS400’s rigid footpegs dragging in tight corners, so we removed the rubber' covers and sawed V/i in. off steel peg rod.^ coated the remaining peg rod with silicone rubber adhesive, hammered the footpeg rubber on as far as possible and secured it with safety wirç running to the frame rail on each side.

The Suzuki’s first race was at Riverside Raceway, a track the rider had raced on before, but one of which he wasn’t very fond—Armco barriers and other hard objects surround several turns and raise the price of making a mistake. During practice, it became obvious that the Suzuki held at least two advantages over its competition: 1) Its front end was rigid, while Hawk forks flex enough through fast esses to cause oversize front tires to rub on the fender bracket and deposit rubber on the front fork tubes; 2) It had more ground clearance than Yamaha RD400s, which suffer from lean-angle-inhibiting underpipe footpeg mounts. With the Dunlop K81s, tire traction wasn’t a problem. Neither was braking—the disc-braked Suzuki would stop as hard as anything in its class.

But the bike also had one serious disadvantage: It didn’t accelerate as hard as, nor have as much top speed as, the Hawks and RD400s. Part of the problem was that the bike had only 500 miles on the odometer, and the engine wasn't completely broken in.

At the start, one RD400 immediately jumped into the lead and disappeared. Riding the Suzuki turned into a case of pass and repass. Hondas flew past off the starting grid and were stuffed at the few Riverside turns requiring use of the brakes on a 400. Then they’d pass the Suzuki again on the nearest straightaway. Two laps from the end it looked like the Suzuki had a certain second place finish. Then Hawk fan Pat Eagan, w ho had started 15 seconds behind the pack for fun, blitzed past (at the entrance to the back straightaway) on his way to victory, relegating the Suzuki to third. Another Hawk rider (who apparently learned something when Eagan went by) sailed into third place on the front straight, holding that position all the way until the seventh turn of the last lap. where he went in too deep under pressure and ran off the track. That restored the GS400 to third place, behind one Hawk and one RD, and ahead of two Hawks, three RD400s and one CB400F.

Besides a chain lube and a fresh set of plugs, the Suzuki received no attention before the next race, held at Ontario Motor Speedway on the same course used when Ontario last hosted an AMA national. This time the AFM had declared the Box Stock class a money race—each division (410, 675, Open) would pay $100 divided between the top three finishers, $50, $35, $15.

The Suzuki seemed to be running faster—it probably had started to break in—and the rider was definitely more comfortable on the super-safe OMS course, which features lots of runoff room and no blind-entry turns. Ontario has enough infield curves to make it possible to compensate for small differences in horsepower and top end through vigorous riding; a better rider with less power can beat a rider with more power. The Suzuki handled perfectly, dragging only the side stand frame mount on a constant-radius 180degree left-hand turn. The bike indicated 1 10 mph on the speedometer, taching 9500 rpm in sixth gear with a slight tailwind, for an actual 108 mph.

On the course used, the starting grid of about 40 machines had to funnel into a narrow, second-gear left hander after running halfway down the straight. Several riders crashed in the first turn; Eagan, (who had started with the pack), and our rider made it through the inside of the mess. The RD rider who had beaten the Suzuki at Riverside ran off the track on the outside, and it seemed the GS400 was safe in second. But then two other RD400s in close formation buzzed past on the back straight, pulled away and entered a 90mph sweeping right-hander with the GS close behind. The RD rider who had run off in turn one came past the Suzuki on a tight inside line, which probably would have led oft' the track if nothing got in the way. Unfortunately, that line and speed put the RD rider on an intersecting path with the two RD400 pilots already on the proper line, and the resulting crash sent bikes and bodies cartwheeling in a cloud of dust. One rider was hospitalized with minor injuries; one survived unhurt but didn’t make the restart of the red-flagged race; and the man who caused it all made the restart but soon retired with problems related to machine crash damage.

As expected. Eagan won the restart by almost a minute. The Suzuki finished an easy second ahead of two Hawks, a Kawasaki Triple and four RD400s. As in all racing, you can’t finish well if you don’t finish. Not crashing counts for a lot.

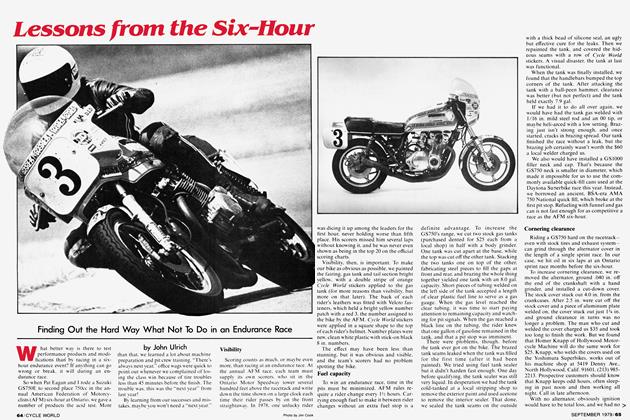

The last AFM race of the 1978 season was held at Riverside Raceway. Because part of the usual motorcycle course was under water and mud from recent torrential rains, the NASCAR course was used. It includes a very long straightaway and bypasses two of the best turns on the track. Since our usual staff-member rider was busy with another Box Stock ride (the Honda CB650), we loaned the GS400 to AFM racer Dain Gingerelli, who has won (with different partners) the 410cc class at the last two annual AFM six-hour endurance races, the most popular endurance event in America (as evidenced by 101 teams entered in 1978). Gingerelli got along well with both the Riverside course and the Suzuki—which again had received no attention between races except for fresh plugs and chain lube.

The Suzuki pulled about 9250 rpm in sixth gear, still lacked both acceleration and top end compared to the Hawks and RD400s entered, but ran better than it had in its first outing at Riverside. The odometer recorded about 630 miles before practice, approximately 130 of which were put on during practice sessions and races at the two previous events. The weather at Riverside was cold and we ran NG K B8ES spark plugs.

The track was puddled with water and soiled by mud and dirt. Riverside is normally mostly straightaway and the NASCAR course features only two turns where the brakes must be applied hard on smaller bikes. But it’s also a deceptive track in places, and there is time to be made up if the rider knows the course.

Eagan led off the start and never looked back. Gingerelli and the Suzuki caught and diced for second place with two Yamahas, one ridden by the man who had caused the pile-up at Ontario, the other ridden by an innocent victim of that crash. Gingerelli kept the faster two-strokes within range by out-riding the competition at two places; holding the throttle wideopen into tricky turn two (a righthand section of the Riverside esses which can be taken, according to Steve McFaughlin, at top speed on a superbike, but which freaks out most club racers); and going into and around turn nine, (a banked righthand sweeper bordered by a steel boilerplate wall backed by an earth embankment), far harder. It paid off. The Suzuki was still third—behind the same two riders as in its first Riverside race—but this time by about six inches, instead of the length of the straightaway. Ahead were the Hawk and one RD400; behind, three Yamahas and two Hondas.

The budget race effort wasn’t cheap. There was no crash damage to repair, no broken or worn-out parts to replace, yet the bill for three races—not counting racing licenses, protective riding gear, initial motorcycle purchase price and the expenses of transportation to the track—came to $230.49. Deducting winnings of $35. the net cost of three races—and more than 190 racetrack miles—came to $195.49. On the other hand, the tires weren't worn out. and probably would have lasted another six or seven races (the bike could have been raced on the stock tires, with restraint). The cost included 15 gallons of gas even though the bike didn't use that much racing—we bought a fresh five-gallon can of gas each race day. and poured the left-over into the van used to carry the bike to the track.

Box Stock racing, although less expensive than competing in many other classes, is not inexpensive. But nothing on the street matches the rush of heading into the first turn with 30 or 40 other guys. Measured in thrill per dollars. Box Stock racing is hard to beat. 151

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWhy the Future Isn't My Secret

February 1979 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1979 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound-Up

February 1979 -

Short Strokes

February 1979 By Tim Barela -

Technical

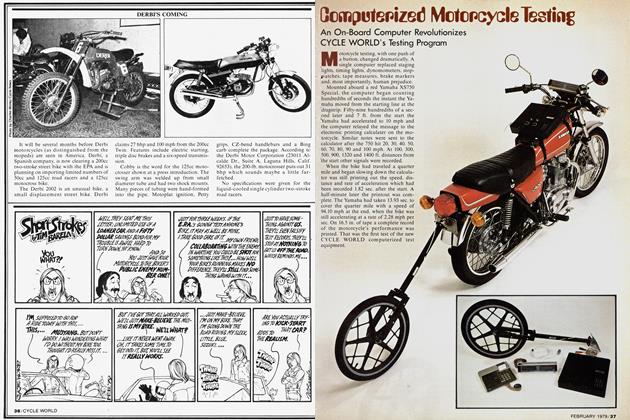

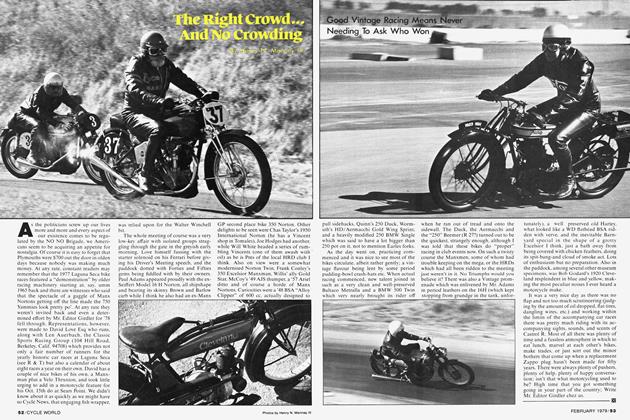

TechnicalComputerized Motorcycle Testing

February 1979 -

Features

FeaturesThe Right Crowd... And No Crowding

February 1979 By Henry N. Manney III