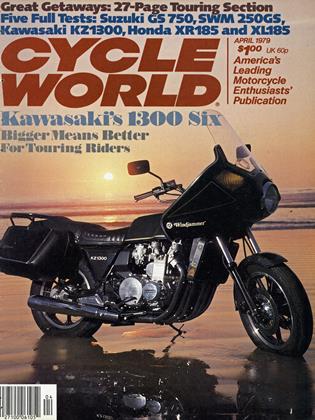

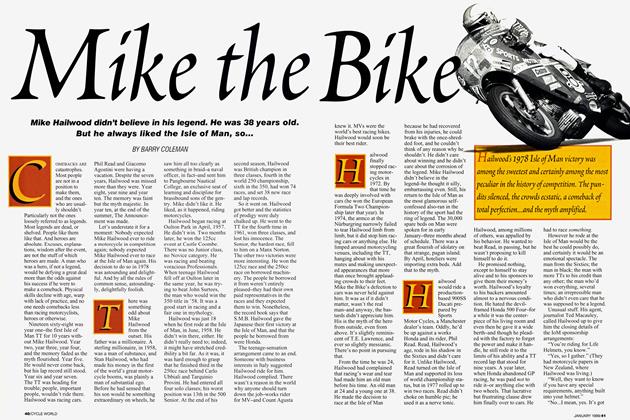

The Professional

Kenny Roberts Is Cool, Analytical, Confident, Friendly, and a Mean Bastard ... A Real World Champion

Barry Coleman

Becoming the world champion was an episode in the life of Kenny Roberts. It was no ambition of his to joust with the Europeans, to gird himself about and vanquish their champion on their turf. He isn't a romantic man. He went because Harleys bite better on dirt than the best-prepared Yamahas and he was wasting his time chasing round behind them. But notice the hidden assumption. it wasn't Roberts who couldn't beat the Americans: it was Yamaha who couldn't beat the Harleys. No one questioned it. Roberts felt the same way about the Euro peans. There wasn't one of them he hadn't beaten. He felt, as a fundamental of policy, that he would beat them again. The vari ables would be provided by Europe itself and Yamaha's ability to build a 500cc road racer.

Forced as it was, there was nothing hasty about Roberts's departure for Europe, but it did bear all the marks of a bad decision. Not for Roberts, because he had nothing to lose in Europe and nothing to win in America, but for Yamaha. Japanese mo torcycle manufacturers tend to have a touching, blinding faith in the machinery they build to win world championships. Yamaha probably thought it was okay to send Roberts to Europe because they he lieved in their new YZR, and thought that he would be able to ride it: and if not. there was always Johnny Cecotto. It was a bad decision. and how bad was underlined by the fact that the factory made only one YZR available to Roberts through Yamaha International. Two is the sensible mini mum, even for an outfit as lean as that of Roberts and Carruthers.

Yamaha has been racing long enough to know the basics. A world championship contender needs two bikes for two equall\ good reasons. First, because damage in flicted at a critical moment during practice may mean sitting out a race and throwing away a championship: second, because invaluable practice sessions are frittered away while the rider waits for wheel changes. suspension settings. carburetion adjustments. and all the other exertions of finesse that get a bike across the line first. But Roberts only had one bike. Perhaps the factory didn't expect it to matter, since they saw, with their customary mathemati cal clarity, what the odds were. At any rate. their attitude seemed to suggest that they had given very little thought to the ques tion of what they were asking of Kenny Roberts, whether it was reasonable, or even decent.

At the beginning of 1978. a lot of people should have considered Kenny Roberts a lot more carefully than apparently they did. No one seriously doubted his ability. though many did doubt its Usefulness in Europe. first time out. And it is undoubt edly true that Roberts's ability alone would not have won him the world cham pionship. What did win it for him was character. His, that of his opponents. and that of European road racing.

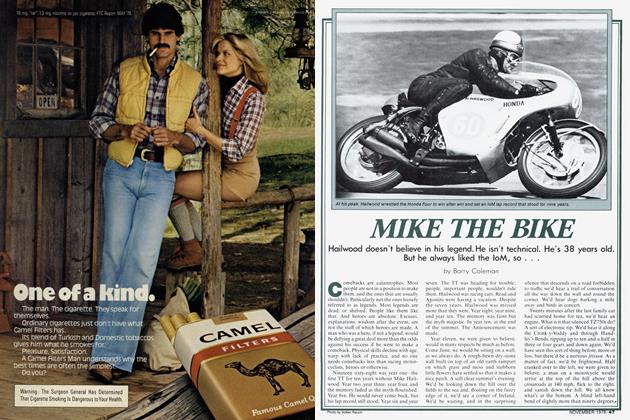

Jr many ways. Kenny Roberts makes a very poor hero. His ability is close to miraculous, and his achievement in win ning the world championship made him not only the most accomplished motorcy clist ever, but one of the world's truly outstanding sportsmen. But people have ridden slower, achieved less, and seemed more marvelous. Some great performers make poor heroes because they have minor personalities, because they are at a loss to explain themselves. Kenny Roberts. on the other hand has a big league personality and he never ceases to describe and ex plain, and he does it with a seasoned flair for the nicely-timed, nicety-turned ex pression. Some performers are poor heroes because they are cool, obsessed. aloof. That's not Roberts. He's warm. easy. corn municative.

Roberts is a poor hero because heroism is no part of his business. He de-mystifies riding a motorcycle fast in order to ride it faster. He avoids festoonIng himself with myth and sporting fancy because, in every sense, he needs to see where he’s going. His business is very concrete. He needs to know all he can about his surroundings and how they relate to him. Whether, for example, he is faster, his bike is faster, or his tires grip better; or which combination of all three. His business is very concrete indeed. Not only does he stand to lose if his judgment starts to mist up: he stands to get hurt. For all these reasons, Kenny Roberts’s view of himself is sharp, simple, clear. The realities of American racing, good advice, timely experience and his own common sense made him that wa>. In Europe, meanwhile, things had taken a different turn.

In Europe, when Roberts arrived, personality, rather than character, and rather even than ability, dominated road racing. There was a seedy corruption, a kind of overblown pomposity about it that produced both illusions and fatal weaknesses. Roberts didn’t directly concern himself w ith that. He just rode his motorcycle. He rode it faster, rode it better, and knew what he was doing. Only Pat Hennen was able to match the clarity of his approach and between them they dominated the early part of the season. Ability apart, Roberts won in Europe for two reasons. First because his character was far better adapted to his work than that of his opponents; second, because Europe attemped to see him in its own terms, fed him through its personality process and came up not merely with a blank, but with a distortion. Life was in fact easier for Roberts because he was so thoroughly misunderstood.

Europe is a wonderful place for mak ing up stories; there’s a rich tradition. For example, a few years ago, a British journalist with a sense of humor penned a goodnatured satire and illustrated it with droll cartoons. One day, the story ran, an Australian sheep farmer was out in the bush when, sitting in the middle of now here, he came upon a small, sandy-haired child. Upon inquiry, it turned out that the child had come from space. Furthermore, he possessed the traditional powers; he could do anything. This, of course, gave the farmer much food for thought. What could he best do with the cosmic prodigy? He took him home and began to think it over. Finally, after deep pondering, he decided. The farmer had always had a feeling that motorcycle racing would be a lot of fun, so why not set the kid at that? Australia, however, was hardly the place for it. So off they went to where the action was: to California. As the kid grew, he became really, really good, as you’d expect. He w'on a lot of races. And he had a nice name. What the farmer called him was Lenny Robot.

Last year, in Amsterdam, a small, blondhaired boy rode a bicycle round the corner of a building, and standing on his pedals as he straightened up, accelerated down a brief concrete strip. He went for a left between two motorhomes, missed the turn, crossed up the bicycle, and slammed sideways into the rear of the second vehicle. The bicycle fell on top of him. Briefly, he considered his position; he picked up the bicycle and rode it away.

Kenny Roberts explains himself in terms of his small, tough son. “I w'as like that,” he says. “Just like that. As a matter of fact, I was a mean bastard. Really mean. That’s all there is to it.”

Europe was expecting something of the sort, Britain in particular. When Kenny Roberts first appeared there, with the Transatlantic Trophy match race team in 1974. he won three races, came second in the other three, and set new lap records on all three circuits. To do that, you have to be some kind of bastard. At the time. Roberts was the AMA Number One. a dirt track racer. It became known that he had ridden in fewer than 30 road races, and that made it serious. What it meant was that certainly reputations, and probably institutions, could be kicked into the guardrail by some little sod who wasn’t even a proper road racer. The British were impressed by Kenny Roberts but they didn’t take kindly to what he implied. And right away, they began to make up stories.

America prepared Roberts for Europe, just as it prepared him for two AMA titles, but not, as the Europeans were to believe, because in some peculiar American way it had made him mean. All sorts of people are mean. Asked, Roberts describes himself as “normal,” and he says he always has been.

Life was in fact easier for Roberts because ' - thon ighly misunderstood.

As a kid he was a normal cowboy, he wore a cow boy hat and sometimes rode his horse to school though mainly he rode a normal bicycle like everyone else. He was small though, and because he was a cowboy, it seemed that he would become a jockey. Evenings and weekends he helped a farmer train Tennessee walking horses, schooldays he fought, didn’t learn much, slid rulers up the girls' butts and did all the normal kind of stuff. He says he was a ruffian. When he got involved with motorcycles, of which he was initially afraid, he used them to conduct water skiing sessions by towing the victims along the canal; and then he began racing them, tw?o years before leaving the school he was supposed to have been going to. Just the normal stuff.

Kenny Roberts had a hard upbringing. Of course he describes it as normal, and so it was in the sense that he understood it perfectly and it did nothing but make him tough and straightforward. There were some plain ethics and plain remedies in the Roberts household. Kenny, for example, fought with his older brother and his mother grew tired of it. “She would send us out in the yard with straps and make us fight,” he recalled, as well he might. “And then, when we had finished, she would strap both of us.” You don't do what Kenny Roberts does without having some forceful influences behind you. When he gets out on the track with a view to riding faster than anyone else and the pace gets to the point where he starts to slide his tires through the fast bends and begins to race " on what he calls the “aggressive” line, he is every inch a mean bastard. And back in his motorhome, he is, as he says, ordinary. Sort of.

When Kenny appeared in 1974, the European press gave very little thought to the critical question of what kind of man -he was. But, in Britain in particular, they quickly formed an impression that had a lot to do with convenient American stereotypes and nothing to do with the real American traditions of which Roberts was a part. To his ultimate advantage, he was entirely misunderstood. The question of, character not only decided the 500cc world championship that Kenny Roberts won in 1978; to some extent it decided it in advance. What Roberts had been in 1974 and what he had become in 1978 were marvelously unrelated to what most Europeans, from press to public to leading competitors, had constructed during those long winter evenings. Lenny Robot was the least of their misapprehensions. They could probably have dealt much better with a robot than with what actually turned up with Farmer Carruthers at the start of the season.

The impact of Roberts on Europe, and of Europe on Roberts, can only be seen against the background of what was there when he arrived. It wasn’t just a question of the quality of the racing. For years, mythology of all kinds, a lot of unclear thinking, and a lot of unstraight talking had confused not only the issues but the participants. An uncritical press had made it worse. There was, to take what turned 4 out to be a supremely relevant example, the question of Barry Sheene’s starting. Sheene, in winning two consecutive world championships, had consistently asserted that his factory machines were little or no different from those of the privateers. He had made a lot of mediocre starts over the " last couple of years, and in coming steadily through the field in race after race had somehow impressed upon Europe the superiority of his skills and the ordinariness of his bikes as being part and parcel of the same thing.

Roberts, from another theater of racing.^ was not like the Europeans. But what set him apart was not his accent; it was simply, and decisively, that he saw them much more clearly than they saw him. He knew, for example, that factories do not send senior riders after world championships on ordinary bikes; and he knew that riders , going for world championships on ordinary bikes, should they start badly, w hich they try most earnestly to avoid, do noti catch up. He also knew who could, and who ce-uld not. start a motorcycle. In short, he knew, though he said nothing, that Europe was suffering from bullshit. When Sheene had to race against Roberts, he started like lightning.

The second coming of Roberts was worse, from the public relations point of view, than the first. The European press had decided in the first place what kind of man he was and the flying drubbings he dished out annually had done nothing to change their mind: he was a cool, secretive man who messed things up for deserving Europeans. It went back to his first appearance, when Roberts had said modest and reasonable things about his riding to w'hich the murderous efficiency of his performances had apparently given the lie. Roberts seemed to be hiding something, if it w'as only a still greater excess of natural ability. He w'as too brash, too confident, arrogant maybe, yes, arrogant, and probably (all being well) he w'as a flash in the pan. In 1978, it was much the same, not only because of what they saw as his personality but because Europe believes a lot of sanctimonious things about what you have to do. be, and say, to count yourself among the greats of road racing, and Roberts was a dirt tracker.

There was barely suppressed panic among those who had most to lose, most clearly expressed by Barry Sheene. Sheene's column in Motor Cycle News was his platform and he began to explain Roberts to Europe in familiar terms. Well, said Sheene, Kenny is really quite a good rider, but he isn’t a threat. You see, Kenny's problem is that he doesn’t know' the circuits, he doesn't know the ropes (the holy mysteries) of the grands prix, he won’t like the travel, the changes of food, the changes of currency, the changes of language, and he will find the competition much hotter than he did w'hen he popped over for the occasional 750 race. Maybe in a couple of years, w'hen he has served his apprenticeship. he wäll be more of a problem. But right now, the pressure is all on him. After all. look what happened to Steve Baker.

More generally, there was a mild social apprehension about how Roberts would fit into the cosmopolitan but relatively cozy grand prix paddock community. Steve Baker had certainly assimilated nicely, pleasant and unobtrusive, but Roberts, it had occurred to some people, was not the same sort of man as Baker. Broadly speaking, Roberts was expected to be aloof, isolated, insanely dedicated and as hostile after hours as he would no doubt be on the track.

There were all sorts of other questions. Would the new works Yamahas be faster than the 1977 models that had sunk Baker and would they be as fast as the new' Suzukis? If they w'ere, would Roberts be able to ride them hard enough? Would Cecotto ride faster? Would Pat Hennen give Roberts more trouble than Sheene? Was Roberts crazy to ride in three classes? They were the kind of questions to which road racing gives short and simple answers. The season began.

The first few races w'ere relatively reassuring. Roberts won at Daytona, which was all right because Daytona w'as in America, wasn’t even part of the world 750 series and he was supposed to have won it years ago. Even Venezuela wasn’t too bad. It w'as a grand prix, but it wasn’t in Europe and it was a strange, indeed a stupid place to hold such a race. True, Roberts won the 250 race and held world championship points and true his 500 fried after a couple of laps but Sheene won the big race and everything was in order. The match races came and went, and Imola, and Paul Ricard, and they too were fairly comforting. Pat Hennen and Johnny Cecotto kept Roberts in line. See? You can’t just come over to Europe and start throwing your weight about. Maybe it wouldn't be so bad after all.

The fatal misapprehension of Kenny Roberts was fully blown at the match races. Pat Hennen scored more points and there was considerable excitement over Roberts’ evident vulnerability. The strain, it seemed, as predicted by Sheene. wras telling. Interest in w'hat Roberts had to say was characteristically minimal. He w'ould, no doubt, have been misunderstood in any case, but what he said pointed all too clearly to what he w'as about to do. “Could you have beaten Pat?” he was asked after the second race at Mallory. “No,” he replied.

“Why not?”'

“Because he w'as going too fast.”

Kenny Roberts walks across the paddock with his arms hitched up a little at the armpits and swinging mildly in time to the walk as if his leathers were a touch too tight. He’s always walked like that, ever since he was a cowboy. It's true, it looks a little like a gunfighter's w'alk. but faster, more cheerful. People have various ways of approaching their motorcycles. Some of the Italians slope moodily over; Sheene's is an intense, slightly hurried affair. Roberts, like Agostini (though much less beautifully). lends to his arrival a sense of occasion: he looks as if he’s going to win. For the spectator, it’s good value. If. on the . other hand, you have something Roberts w'ants. like the w'orld championship, it can’t be very reassuring to walk behind him as he makes his way to the grid. Worse. * maybe, because he smiles amiably all the way to his bike.

When Kenny arrives for one of the social functions spawned by racing, he usually wears the uniform provided by his sponsor. His hair is tidy, he looks neat, and he stands politely about waiting to fall into conversation with someone. He has an amused, slightly unreliable look in his blue eyes (as if only he is aware that the main speaker’s suspenders are saw'n halfthrough but everyone will know it when his pants fall dowm) until he begins to talk about racing. Kenny Roberts can get pretty -» loud. His voice, in any case, like his appearance, has a firm, if not sharp edge, and when the time comes to raise it, he raises it. But when he begins to talk about his racing, his work, his voice softens, and his eyes harden, just a shade. He will concentrate, and talk, for hours, and w'hat he says ^ is often very vivid, and very complex.

When he rides his motorcycle, w hen he does his work, it seems that the process intensifies. Photographs show his eyes, narrowed, expressing nothing. Eyes are for seeing, and used to the limits of their purpose, carry no messages. And there are presumably no voices inside the Roberts helmet; just fast and silent calculation.

Continued on page 167

continued from page 88

he Spanish Grand Prix, at Jarania. , near Madrid. in April. was the first European round and Roberts began at once to do what he had come to do. He led the 500cc race in Spain until his throttles began to stick, and in the end he came second. He led the 250cc race until his tires began to ball up and in the end he came second in that too. The results in Spain were certainly' interesting, both because Roberts had found that his YZR Yamaha was as fast as the works Suzukis of Sheene nd Hennen and because he had found that he could ride it fast very much sooner than he had expected to. He already knew how to ride the 750s and 250s. The 500s ere another matter. Of course, he could get on it and ride it fast; he knew that. But world championships are won in a narrow jealm well beyond what we would think of as fast. Roberts had to find out, above all else, how much throttle would produce how much drift in a variety of situations. fter Jarama, with its violently quick suc cession of bends, give or take a little, he knew. He was surprised, and encouraged. Spain emphasized that technology, not ability, was going to be his problem. And character, the element that decided the title, was going to be a problem for the others.

Something significant happened before Kenny Roberts took part in his first Euro pean grand prix: he was refused an entry. There are a number of possible explana tions for what at first sight appears to be an outburst of conventional and entirely charaderistic stupidity. It may be (though you will doubt it) that the organizers had never heard of Kenny Roberts. (They said that whoever he was, he had no world championship points from the previous year and wasn*t entitled to rideS) More likely is that they knew perfectly well who he was, that they didn~t like the sound of him, and that they wanted to assert their authority over him, to put him down, before it was too late. That is the sort of thing that happens to European riders all the time. It tends to make them, slightly hut markedly, nervous and abject. In that frame of mind, two things happen to them. First, they don't ride as well as they should. Second. they are the usually silent, mostly willing victims of one of the most appall ing sporting scandals of all time.

Kenny Roberts hadn4t been in Europe long before he realized in full what con fronted grand prix riders. Because they need points, they ride in the FIM's races. The races attract anything up to 130,000 spectators. who will pay say $12 each. The riders are usually paid the FIN'l minimum. Several times last year Kenny Roberts rode for $200 and very rarely did he ride in a grand prix for much more. “I hate this.” he said at once, “But it isn’t so bad for me, because I’m being paid by Yamaha. But what about the privateers? It's disgusting. These organizers are bastards.”

Roberts hadn’t declared himself at the time of the Spanish rebuff, but the collective unconscious instinct of Spain, of Europe, was right. By the end of the season he was talking lawyers, and the European riders had begun to look to him for encouragement, if not leadership. He is a very straightforward man. He did not react to the refusal of his entry by the Spanish organizers as a European might. He went out on their track and set a newlap record on it; four months later, he had won their world championship.

Spain saw’ Kenny take to the social life of the paddock. Socially, there are two kinds of riders, the ones who live in the paddock in trailers, and those who live in fancy hotels and commute to the paddock in fancy cars. Roberts, with his rather grand motorhome, which he drove all over Europe (“It wasn’t far,” he would say of a 2000 mi., six-country journey) was a paddock-dweller. One of the lads, just the normal stuff. While his team worked on his machinery. Roberts was off to meet his workmates.

They didnt know what to make of it. Europe knew that Kenny Roberts was a cool. spikey operator. The little guy from the fancy motorhome. on the other hand. had an easy. friendly manner and a sur prisingly innocent-looking grin. The initial explanation was simple: he was psyching people out, all this calling across the paddock, asking people how they were doin’. It didn't fool the old hands. They’d seen it at? before. Psyching tactics. But everyone? 125 riders; 50 riders; psyching out the whole paddock? Wasn’t that overdoing it, even, for an American?

What set him apart was not his accent; it was simply, and de cisively, that he saw them much more clearly than they saw him.

The truth soon dawned, and the truth. for some, was awful. Kenny Roberts was just plain friendly. Norma!. What it meant was that Roberts, far from being perplexed by his strange new environment, was at his ease in it. enjoying it. Far from feeling the predicted pressure of being away from home, being in foreign countries with all their peculiar little differences, Roberts thought it was fun. By the end of th~ season he was feeling awkward about not being able to do the ordinary things like golf and tennis at the ordinary times but in the meantime he didn't give a damn about~ the food, and the travel and the currencies, and all the stuff that was supposed to bring him down. He was, as he said. ordinan~ Just an ordinary friendly American in the ordinary American tradition. "The trouble with me," he remarked. on noticing how much time he spent shooting the breeze,' is that 1 like everyone."

But that wasift trouble. Composed, amiable and at home in a multi-lingual, multi-cultural, multi-everything traveling circus, he was twice as dangerous as the Lenny Robot Europe had been expecting.

While Roberts was settling down, the defending champion was becoming more and more disconcerted. In terms of his ability, Kenny Roberts is not by any means ordinary but he should not have won the 500cc world championship in 1978: Barry Sheene should have won it. Sheene, however, having mis-read Roberts in the first place, compounded his error. Had he said in his column that he would wear Roberts down because Goodyear knew next-tonothing about racing motorcycles in Europe and nothing at all about what would happen to the best of their tires when Roberts put them on a 500, and had he pointed out that, of all the mind-bogglingly stupid things, Roberts had only one YZR500, he would have been on to something. Something, furthermore, with which Roberts would have been forced to agree. Then, for good measure, he could have added the difficulties of learning a dozen new tracks in a few laps of training apiece. Those were Roberts’s real problems, and they almost overcame him.

Roberts didn’t have to race directly against Sheene until the Dutch TT in June. Hennen and Cecotto were consistently beating Sheene, and Roberts, in winning in Austria. France and Italy, left him a long way behind. Sheene felt called upon to explain himself, but he didn't favor the terms used by Roberts. It was never a question, according to Sheene, of other people going faster.

Sheene said he was ill, suffering from something nasty he had collected in Venezuela. Paddock skeptics with a medical bent pointed out that two or three hundred other people had been to Venezuela and come home unscathed. The virus may have affected Sheene’s temper as well as his stamina (the virus allowed him to come third, but not to wan) since he began to be short w ith journalists, refusing to speak to some and falling out with others who ventured opinions different from his own. He began a long and obviously debilitating campaign against those elements of the media that refused to get in line. His problem lay largely with the non-specialist media. The enthusiast press continued to repeat his point of view without question or comment. The result was that most enthusiasts in Britain and Europe were offered a strong impression of Sheene as a suffering, if not wronged, hero while their impression of Roberts as a clinical hatchetman was undisturbed. Meanwhile, Sheene apparently continued to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Roberts apart. The Yamahas, he said, were 20 mph faster than his Suzuki; his Michelin tires weren't as good as Roberts's magic Goodyears and anyway, he wasn’t feeling well. The paddock wits did nothing to calm him down. That’s right, they said, Sheene’s got a virus. But it doesn’t come from Venezuela. It comes from California, and it’s carried by Goodyear tires. Far from home as he was, it wasn’t Kenny Roberts who was going to pieces.

like Agostini, tends to I a sense o.f occasion.

Roberts was inclined to view all this with detachment. He saw no reason to comment on Sheene’s psychological readiness, but he remembered that Barry had written him off at the beginning of the season. “That was a dumb thing to do,” he opined. “It’s okay saying I’m no good, but if I’m no good and I beat him. what does that make him?” He saw it as a matter of ill-judged tactics, and it had no discernible effect on him. “In Camel-Pro, we just don't have that kind of crap. We go out there on our motorcycles and race them. The winner is the one who comes in first and that's that. And we don’t have anything to say about it, except maybe to wish we’d damn well gone faster.”

After the Dutch TT Roberts led the 250cc class as well as the 500. and wasn’t far behind Cecotto in the 750 running. (The F750 championship was run at different venues, at different times.) It seemed that he might win three world championships at one sitting, his first. After Holland, however, things began to fly apart.

The 250 was the first to go, in Belgium. The start at Francorchamps is downhill into a left-and-right kink followed by a sharp climb. The losing end of the field was halfway up the hill when Roberts finally stopped running and started riding. He looked a bit silly, and it’s fair to assume he was angry. At the end of the lap, he pulled in. He handed his bike to Trevor Tilbury, vaulted the pit wall, and strode into the paddock. It’s traditional in Europe to remonstrate when mechanical failure costs you a world championship, to look at the bike, to look under, to slice the air with anguished gestures, to be seen, to be aggrieved. Roberts didn’t give the bike a second glance. Over a cup of tea, he thought about the 500. Emotionally, intellectually, the racer Roberts is very spare? very efficient indeed. ,

Roberts didn’t like most of what he encountered in European racing, and saUi so. Belgium encapsulated not only w hat he didn't like, but how' he dealt w'ith it. Kenny Roberts doesn’t race a motorcycle because racing is death-defying; he races because he is good at it. He wishes very much that it were not inclined to hurt, let alone to kill. Some Europeans, some British in particular, cherish brutal, if not sadistic assumptions about the nature of road racing. To, reasoned propositions to improve safety they will eventually say: “Next, you wiff want the circuit lined wûth foam rubber.” They imply softness, cowardice. Kenny* Roberts at this point will say: “Listen. 1 don’t want the circuit lined in foam rubber. 1 want the circuit lined in cotton wool, and if I could race on a soft rubber surface instead of a hard road, I’d want that too* Though arguing is popular in motorcycle racing, no one has yet called Roberts acoward.

Francorchamps is a circuit made up <Jf public roads and is the fastest in the w'orld, with a lap record of 137.15 mph. Roberts didn't like it; not because of the speed, or even because of the houses, walls, trees, and telegraph poles snuggling so inti-^ mately up to the trackside. He didn’t like it because of the surface. Roberts rides w i his brain rather than his backside, but he needs precise, reliable and predictable feedback from his tires. He likes to slide them, but he likes to know how far they are sliding, and wffiy. A public road surface, dosed as it is with fuel. oil. and rubber, is too well, and too patchily, lubricated.t Roberts won’t slide his tires on such a ..................—........................... ' '...........-“TT surface and that puts him back on a trac-"' tion level with the Europeans, who won’t ^ slide them at all.

The truth SOOfl: dawiwd, and the truthq. for s(Hne, was awfuL.

Belgium had the common background of the grands prix. The facilities were bad. the paddock dangerously small and crowded. the organizers w'ere unhelpful and Roberts, like everyone else, was being* ripped off. But he had to race on the track. First, it rained during practice, then both " his 500 and his 250 seized, and he only go4t in a couple of laps on each. (It shows probably better than anything he did all season how good he is that he qualified fifth-fastest, using Cecotto’s spare bike./ Then, it rained during the race.

Belgium represented in frightening"4 measure everything that might reasonably have stopped Roberts. Wil Hartog (who became Barry Sheene’s teammate after Pat Hennen’s crash at the Isle of Man) won in Belgium. Kenny Roberts came seconds ahead of Barry Sheene. It was an astonishing performance. Roberts wasn’t prepared J to follow1 Hartog through puddles on roads of that kind at 170 mph. so he eased off a liiile, to maybe 166 or so. But he beat Sheene, who was not only the world champion. but the lap record holder. Hartog was on intermediate tires; Roberts was on dryiîsue slicks.

continued on page 189

continued from page 170

Roberts led the 500cc series fairly comfortably from Sheene when he set off for tl^ two Scandinavian rounds, and led it by the skin of his teeth when he came back. The twin evils of a heavy tire-testing schedule and having only one bike, which had menaced the project from the outset, caught Roberts squarely in Sweden and F>egan, finally, to work him over. Riding too fast on a new tire, trying to slide it hard enough to retain a useful impression from one practice session to the next put Roberts in the hospital. Still concussed, he finished seventh in the race while Sheene, shadowed by Hartog, won. Since Hennen’s ■crash, Sheene had become the statistical problem. He and Roberts faced each other oti the points table, but they rarely met on the track. They both broke down in Finland, and they arrived in England with yiree points separating them.

Composure was critical to the two remaining rounds. Roberts narrowly led the championship but Sheene was riding at h*'»me. In media terms, he was very much at home. In a radio interview the day before the race he condemned the entire sport, complaining that it was “full of hypocrites,” and said that the press would typund him into taking up a career as a Formula One car driver. He said of the „race that now he was not expected to win, the pressure was all on Roberts. Kenny, meanwhile, said nothing except that he \^as pleased to be back on a real race track and glad to have, at last, a second bike to ease the pressure during practice periods. Silverstone was to produce a special test of ^elf-possession and it was Sheene, at home, and not Roberts, the stranger, who Vas to fail it.

Roberts didn't like most of what he encountered in European racing, and said so.

The British Grand Prix was a mess. Roberts won, after fearsome rain had caused a mid-race tire change. Sheene rode faster after the change to rain tires, èut Carruthers changed Roberts’s wheels much faster. Sheene was third, behind -Steve Manship, a British rider who had chosen to start on intermediate tires and \$as able to stay out on the track.

Amid confusion, there were disgraceful scenes on the victory rostrum. The presenter was among those who wasn't sure what had happened and chose the middle of the American anthem to ask Sheene for his version. While the Star Spangled Banker played and Roberts, who takes the matter of being his country’s representative seriously, held his trophy aloft, Sheene declared to a striking musical accompaniment that he had been told that Steve Manship or Marco Lucehinelli had won. but that it definitely wasn’t Roberts. The anthem was faded out. As Roberts left the rostrum, he said he would be in his motorhome and when they had figured out who had w'on, he would be grateful if they would let him know'.

The crow d, which was robbed of a spectacle both by the weather and by indecisive management, was hostile to Roberts, whom they saw as the culprit rather than as another victim (he took the points, but he had wanted the race stopped). But then, British enthusiasts have been led to believe all manner of things about Kenny Roberts. He didn’t care to be booed, but he was unaffected. “No, I don’t like it.” he said. “But for years 1 have been an outsider in America. They never liked me racing Yamahas on the dirt against all those Harleys, and they used to boo me once in a while. They used to throw beer cans at me at Louisville. When you’ve been to Louisville to race against the Harleys, you can take a little booing.” It had never occurred to Europe that Kenny Roberts had been an outsider all his professional life, just as it had never registered that he had done more traveling per year in the States than he would do in Europe in two seasons. Roberts’s reaction to hostile crowds was again in stark contrast to Sheene’s attitude. Sheene, in his public pronouncements, seemed mesmerized by what he called “the knockers.” In fact, there was little or no evidence of his being knocked and crowds everywhere were warmly receptive w henever he rode, win or lose. None of the things that Sheene actually pointed to as the cause of his dow nfall were substantial. The one solid problem he had was Kenny Roberts, and Kenny Roberts was none of the things Sheene had said he would be.

It had never occurred to Europe that Kenny Roberts had been an outsider all his professIonal life.

At the final round, at the Nurburgring, in Germany, two weeks after Silverstone, Roberts still hadn’t gone to pieces. He faced learning 14 miles of the world’s most infamously dangerous racing circuit and he broke the lap record in unofficial practice and came third in the race by forcing himself to go slowly on an over-jetted bike. Sheene came fourth. Roberts w'as the world champion. At the presentation that evening, the first people he thanked were the privateers, for putting up with so much to make the racing possible. He wouldn't, he said, be thanking the organizers, because they got enough thanks as it was.

In winning the 500cc world championship. having twice been AMA champion. Kenny Roberts became perhaps the first real world champion. His ability to ride a motorcycle, finally, defies analysis. Roberts, who has an analytical turn of mind as well as a lot of patience, will try to explain it, to describe it, certainly to de-mystify it, every way he knows how. How he balances, how he slides, how he accelerates, how he brakes, how he uses line. In the end, he often tails off, slightly confused. Because in the end, he doesn't quite understand it either. What he says, what he said an hour after he'd won the world title, is that he’s just an ordinary rider.

What we know is that he rides a motorcycle faster and harder than anyone else in the world. Further, he knows precisely when and where to do it, and when to ease off. We can measure his ability in terms of the world championship he shouldn't have won. Racing a kind of motorcycle he had never seen before, using tires that were new to him, on tracks he had never seen, with inadequate practice time, with no spare machine and no previous experience of a strange and complicated way of life, he took the title from a man with three factory bikes and almost 10 years’ experience of grand prix racing. It was the work, by and large, of a mean bastard.

It was also the work of a man determined to be normal. Being what he calls normal is more for Kenny Roberts than a statement about how he happens to be. It's a professional priority. Since in many ways it isn't true, it's a device, a psychological ploy. At the end of the day, it's a way of beating people.

What Roberts did last year, he will probably do again this year, because his character won’t change and his skill will develop rather than diminish.

Not that it’s a deception. Roberts, given the nagging fact that he is the best in the world at what he happens to do, is indeed a straightforward and unaffected man. But neither is it an accident. There are a lot of other ways to be, and well Roberts knows it; but mental and emotional sleight of hand, self delusion, don't help a world class motorcyclist for long. It isn't puritanism; it's policy. Kenny Roberts doesn't have to worry about keeping his feet on the ground. It’s nothing to do with what Grandma had to tell him. What he has to keep on the ground are his wheels.

What Roberts did last year, he will probably do again this year, because his character won't change and his skill will develop rather than diminish. Last year was an episode; this year will be another. And what he did to the Europeans, he would probably do, given machinery, to the Americans. Perhaps because he's normal. And perhaps because he's a mean bastard. Really mean. And perhaps that’s all there is to it.