Mike the Bike

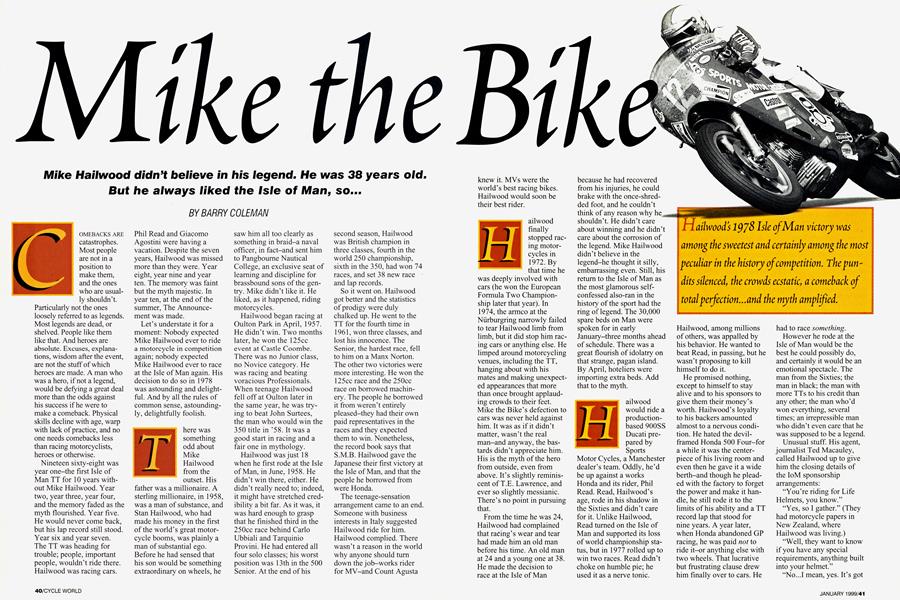

Mike Hailwood didn’t believe in his legend. He was 38 years old. But he always liked the Isle of Man, so...

BARRY COLEMAN

COMEBACKS ARE catastrophes. Most people are not in a position to make them, and the ones who are usually shouldn’t.

Particularly not the ones loosely referred to as legends. Most legends are dead, or shelved. People like them like that. And heroes are absolute. Excuses, explanations, wisdom after the event, are not the stuff of which heroes are made. A man who was a hero, if not a legend, would be defying a great deal more than the odds against his success if he were to make a comeback. Physical skills decline with age, warp with lack of practice, and no one needs comebacks less than racing motorcyclists, heroes or otherwise.

Nineteen sixty-eight was year one-the first Isle of Man TT for 10 years without Mike Hailwood. Year two, year three, year four, and the memory faded as the myth flourished. Year five. He would never come back, but his lap record still stood. Year six and year seven.

The TT was heading for trouble; people, important people, wouldn’t ride there. Hailwood was racing cars.

Phil Read and Giacomo Agostini were having a vacation. Despite the seven years, Hailwood was missed more than they were. Year eight, year nine and year ten. The memory was faint but the myth majestic. In year ten, at the end of the summer, The Announcement was made.

Let’s understate it for a moment: Nobody expected Mike Hailwood ever to ride a motorcycle in competition again; nobody expected Mike Hailwood ever to race at the Isle of Man again. His decision to do so in 1978 was astounding and delightful. And by all the rules of common sense, astoundingly, delightfully foolish.

here was something odd about Mike Hailwood from the outset. His father was a millionaire. A sterling millionaire, in 1958, was a man of substance, and Stan Hailwood, who had made his money in the first of the world’s great motorcycle booms, was plainly a man of substantial ego. Before he had sensed that his son would be something extraordinary on wheels, he saw him all too clearly as something in braid-a naval officer, in fact-and sent him to Pangboume Nautical College, an exclusive seat of learning and discipline for brassbound sons of the gentry. Mike didn’t like it. He liked, as it happened, riding motorcycles.

Hailwood began racing at Oulton Park in April, 1957. He didn’t win. Two months later, he won the 125cc event at Castle Coombe. There was no Junior class, no Novice category. He was racing and beating voracious Professionals. When teenage Hailwood fell off at Oulton later in the same year, he was trying to beat John Surtees, the man who would win the 350 title in ’58. It was a good start in racing and a fair one in mythology.

Hailwood was just 18 when he first rode at the Isle of Man, in June, 1958. He didn’t win there, either. He didn’t really need to; indeed, it might have stretched credibility a bit far. As it was, it was hard enough to grasp that he finished third in the 250cc race behind Carlo Ubbiali and Tarquinio Provini. He had entered all four solo classes; his worst position was 13th in the 500 Senior. At the end of his second season, Hailwood was British champion in three classes, fourth in the world 250 championship, sixth in the 350, had won 74 races, and set 38 new race and lap records.

So it went on. Hailwood got better and the statistics of prodigy were duly chalked up. He went to the TT for the fourth time in 1961, won three classes, and lost his innocence. The Senior, the hardest race, fell to him on a Manx Norton. The other two victories were more interesting. He won the 125cc race and the 250cc race on borrowed machinery. The people he borrowed it from weren’t entirely pleased-they had their own paid representatives in the races and they expected them to win. Nonetheless, the record book says that S.M.B. Hailwood gave the Japanese their first victory at the Isle of Man, and that the people he borrowed from were Honda.

The teenage-sensation arrangement came to an end. Someone with business interests in Italy suggested Hailwood ride for him. Hailwood complied. There wasn’t a reason in the world why anyone should turn down the job-works rider for MV-and Count Agusta knew it. MVs were the world’s best racing bikes. Hailwood would soon be their best rider.

ailwood finally stopped racing motorcycles in 1972. By that time he was deeply involved with cars (he won the European Formula Two Championship later that year). In 1974, the armco at the Nürburgring narrowly failed to tear Hailwood limb from limb, but it did stop him racing cars or anything else. He limped around motorcycling venues, including the TT, hanging about with his mates and making unexpected appearances that more than once brought applauding crowds to their feet. Mike the Bike’s defection to cars was never held against him. It was as if it didn’t matter, wasn’t the real man-and anyway, the bastards didn’t appreciate him. His is the myth of the hero from outside, even from above. It’s slightly reminiscent of T.E. Lawrence, and ever so slightly messianic. There’s no point in pursuing that.

From the time he was 24, Hailwood had complained that racing’s wear and tear had made him an old man before his time. An old man at 24 and a young one at 38. He made the decision to race at the Isle of Man because he had recovered from his injuries, he could brake with the once-shredded foot, and he couldn’t think of any reason why he shouldn’t. He didn’t care about winning and he didn’t care about the corrosion of the legend. Mike Hailwood didn’t believe in the legend-he thought it silly, embarrassing even. Still, his return to the Isle of Man as the most glamorous selfconfessed also-ran in the history of the sport had the ring of legend. The 30,000 spare beds on Man were spoken for in early January-three months ahead of schedule. There was a great flourish of idolatry on that strange, pagan island. By April, hoteliers were importing extra beds. Add that to the myth.

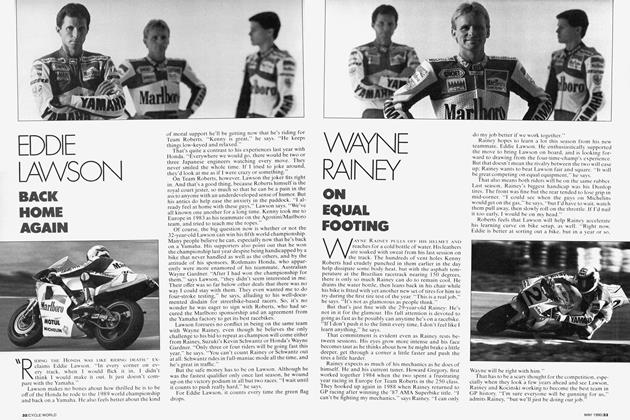

ailwood would ride a productionbased 900SS Ducati prepared by Sports Motor Cycles, a Manchester dealer’s team. Oddly, he’d be up against a works Honda and its rider, Phil Read. Read, Hailwood’s age, rode in his shadow in the Sixties and didn’t care for it. Unlike Hailwood, Read turned on the Isle of Man and supported its loss of world championship status, but in 1977 rolled up to win two races. Read didn’t choke on humble pie; he used it as a nerve tonic.

Hailwood, among millions of others, was appalled by his behavior. He wanted to beat Read, in passing, but he wasn't proposing to kill himself to do it.

He promised nothing, except to himself to stay alive and to his sponsors to give them their money's worth. Hailwood's loyalty to his backers amounted almost to a nervous condi tion. He hated the devilframed Honda 500 Four-for a while it was the center piece of his living room and even then he gave it a wide berth-and though he plead ed with the factory to forget the power and make it han dle, he still rode it to the limits of his ability and a TT record lap that stood for nine years. A year later, when Honda abandoned GP racing, he was paid not to ride it-or anything else with two wheels. That lucrative but frustrating clause drew him finally over to cars. He had to race something.

However he rode at the Isle of Man would be the best he could possibly do, and certainly it would be an emotional spectacle. The man from the Sixties; the man in black; the man with more TTs to his credit than any other; the man who'd won everything, several times; an irrepressible man who didn't even care that he was supposed to be a legend. Unusual stuff. His agent, journalist Ted Macauley, called Hailwood up to give him the closing details of the loM sponsorship arrangements:

"You're riding for Life Helmets, you know."

"Yes, so I gather." (They had motorcycle papers in New Zealand, where Hailwood was living.)

"Well, they want to know if you have any special requirements, anything built into your helmet."

mean, yes. It's got to have a hole in the front.’ Still not much of a technical man.

ailwood probably never thought of changing his mind. Nonetheless, what he had bitten off began to be hard to chew. The Isle of Man was overloaded, oversubscribed. More people than ever before had shelled out to see motorcycle racing, to see Hailwood. Hailwood took it seriously, more so than he had originally intended.

At his first pre-IoM test session, at Oulton Park one sodden day not long after dawn, he looked old, scraggy, peculiar. His hair, such as it was, was wet, lank. He didn’t look convincing. No one who didn’t know about the myth would have believed that anything of any importance could be pinned on this polite, unlikely, rainsuited figure.

There was, it must be said, a general feeling that it would be nice just to see Hailwood ride around the Island. In the unbaffled euphoria following The Announcement, people had been ready to predict that Hailwood would win. As the event came closer, there was a certain amount of backing off. That he would win became a much more privately held possibility. Sensibly speaking, it didn’t really seem much of a likelihood. The motorcycle papers made pre-race predictions. The best Hailwood was offered by one of them was sixth in the F-l class. Honda Britain, meanwhile, defending the F-l title, announced to the accompaniment of a stinging denial that they had turned Hailwood down. What they said was that Hailwood was a certain loser, a oncegreat rider who had no hope of meeting current standards. They might have lent him a bike for a demonstration lap, they remarked with impressive condescension, but that was all. One way and another, the scene of sincere consolation was being discretely set.

On the first night of official practice, Hailwood took the Sports Ducati out and broke the F-l lap record. Confidence in Hailwood took a boost. But while he was gaining speed on the Ducati, several others went faster still. One of them was Phil Read. On Thursday, he lapped at over 109 mph. F-l was essentially a silhouette class. Frames were a freefor-all and engine modifications were almost unrestricted. If Read’s works Honda wasn’t a faster bike, it should have been. A dealer-entered V-Twin started and finished as the mechanical underdog, and Read’s time seemed decisive. Hailwood was 6 mph slower and there was a ripple of indignation that the great man should be put at such a disadvantage. But that was Thursday.

On Friday, Hailwood did something sensational. He rode around the TT course at more than 111 mph on what amounted to a beefed-up streetbike. Not only was it 2 mph faster than Read; it was just over 1 mph short of the absolute IoM record. But that record was held by the fastest one-off racer the Kawasaki factory knew how to make. The Island was astonished, and Read was stung. Finally, just one last time, Mike Hailwood had set Phil Read’s nerves clattering. It was a masterpiece of destructive psychology, and Hailwood was plainly pleased with it.

ame the race and Hailwood won. By that time, because of the way the week had developed, there was no outstanding theoretical reason why he shouldn’t. There was a credibility lag. All of what was happening seemed too corny to be true.

At Allacraine on the first lap, Hailwood was 4 seconds up on Tommy Herron, a strong contender aboard a Mocheck/Y oshimura Honda. Hailwood held his lead, but Herron hung on a few seconds behind until, leaping the brow at Rhencullen, he broke his frame. Next man down, and well down, was Read, riding the bike that was too good for Hailwood. Read had started 50 seconds ahead. Halfway through the third lap, Hailwood caught him on the road. They raced through Ramsey together, over the Mountain and into the pits for the required refueling stop. Read and Hailwood. It was an eerie moment, a mass fantasy made dangerous reality because too much wishing had made it so.

Courtesy of his car injuries, Hailwood pushstarted with a limp and while Read hustled away, the refueled Ducati was slow to fire. But Hailwood had caught up by Ballacraine and this time he was ready to go past. He said later that it was no trouble. Read, in reply, gave the Honda its all-and blew it up. “I had to,” he said later in the bar, and no doubt he was right.

Hailwood’s victory was among the sweetest, and certainly among the most peculiar, in the history of competition. The pundits silenced, Honda crushed, the crowds ecstatic, a comeback of total perfection...and the myth amplified. Even when he stood on the rostrum the apparent facts strained credulity. It was a ripping yam, a damn good bedtime story for the reasonably imaginative infant, but not the sort of stuff you serve up for adults. But they gave Hailwood the garland, and he walked away with tears in his eyes.

ailwood’s early Isle of Man glory aboard the SS Ducati was followed by a week of disappointment on Yamaha two-strokes, which confounded him with a balky steering damper (TZ500), a peaky powerband (TZ250) and a broken crank (TZ750). Hailwood, in conversation in the hotel bar, was asked once too often, once too incoherently, for his autograph. He declined the preferred ballpoint and looked into the distance, claiming anonymity.

“But you’re him...you’re Hailwood.” Drunk and puzzled.

“No, sir. Though I am often mistaken for him.”

“But you’re Mike the Bike.” Losing confidence. “Aren’t you?”

“No, sir. Though I must say I wish I was. Yes, I wish I was.”

Mike Hailwood, 38, marine-engine concessionaire of Christchurch, New Zealand, was married with two children. His hobbies included swimming, music and motorcycling. □

This story was excerpted from an article that ran in the November, 1978, issue of Cycle World. Tragically, Hailwood and his daughter Michelle died three years later in an automobile accident. Mike the Bike is missed still.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGeneral Stupidity

January 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsPaperweights of the Gods

January 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCHot Oil Massage

January 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1999 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley Hot-Rods the Dyna Glide

January 1999 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupKtm Unveils Ultralightweight Thumper

January 1999 By Jimmy Lewis