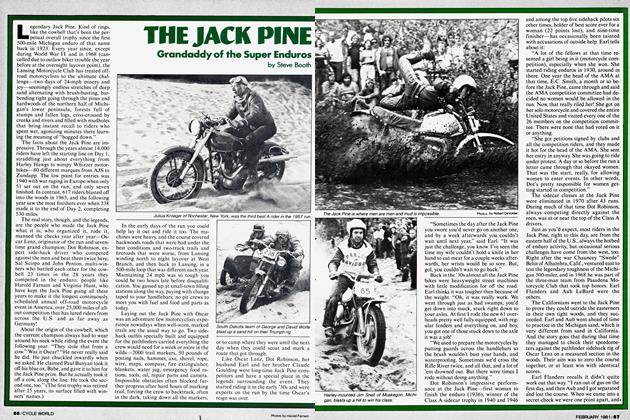

YOUR FIRST ENDURO

You won't win money and you won't thrill the crowd. Enduro riding is just a way to have fun.

Steve Booth

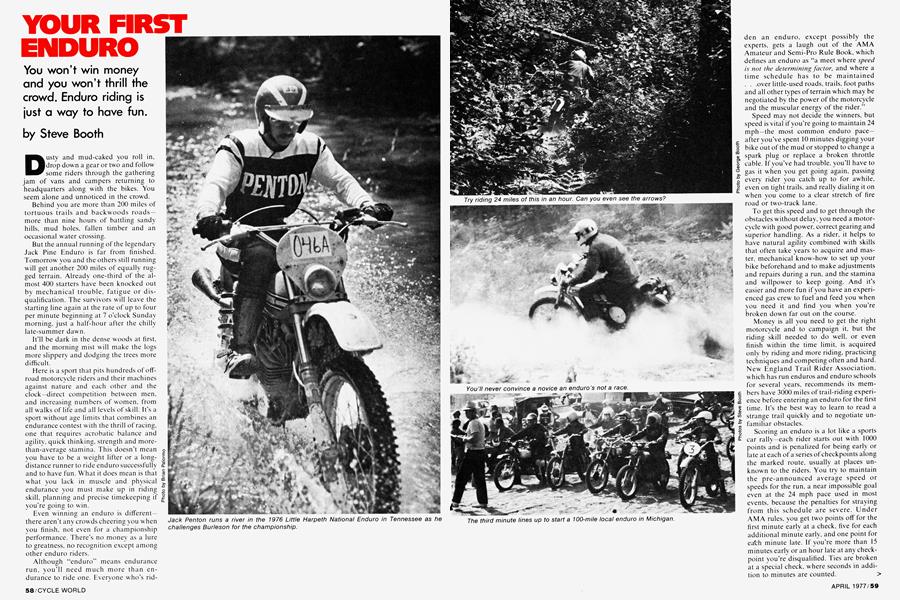

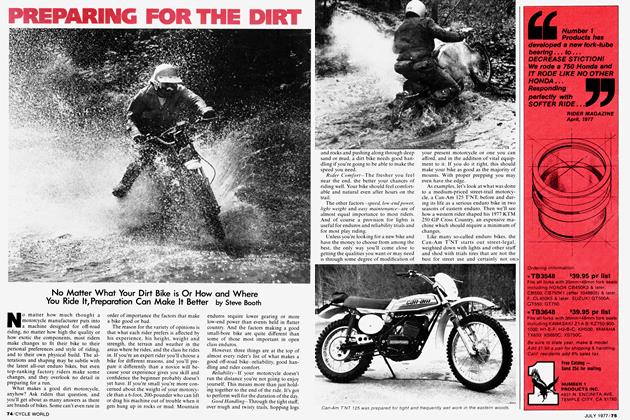

Dusty and mud-caked you roll in, drop down a gear or two and follow some riders through the gathering jam of vans and campers returning to headquarters along with the bikes. You seem alone and unnoticed in the crowd.

Behind you are more than 200 miles of tortuous trails and backwoods roads— more than nine hours of battling sandy hills, mud holes, fallen timber and an occasional water crossing.

But the annual running of the legendary Jack Pine Enduro is far from finished. Tomorrow you and the others still running will get another 200 miles of equally rugged terrain. Already one-third of the almost 400 starters have been knocked out by mechanical trouble, fatigue or disqualification. The survivors will leave the starting line again at the rate of up to four per minute beginning at 7 o’clock Sunday morning, just a half-hour after the chilly late-summer dawn.

It’ll be dark in the dense woods at first, and the morning mist will make the logs more slippery and dodging the trees more difficult.

Here is a sport that pits hundreds of offroad motorcycle riders and their machines against nature and each other and the clock—direct competition between men, and increasing numbers of women, from all walks of life and all levels of skill. It’s a sport without age limits that combines an endurance contest with the thrill of racing, one that requires acrobatic balance and agility, quick thinking, strength and morethan-average stamina. This doesn’t mean you have to be a weight lifter or a longdistance runner to ride enduro successfully and to have fun. What it does mean is that what you lack in muscle and physical endurance you must make up in riding skill, planning and precise timekeeping if you’re going to win.

Even winning an enduro is different— there aren’t any crowds cheering you when you finish, not even for a championship performance. There’s no money as a lure to greatness, no recognition except among other enduro riders.

Although “enduro” means endurance run, you’ll need much more than endurance to ride one. Everyone who’s ridden an enduro, except possibly the experts, gets a laugh out of the AMA Amateur and Semi-Pro Rule Book, which defines an enduro as “a meet where speed is not the determining factor, and where a time schedule has to be maintained . . .over little-used roads, trails, foot paths and all other types of terrain which may be negotiated by the power of the motorcycle and the muscular energy of the rider.”

Speed may not decide the winners, but speed is vital if you’re going to maintain 24 mph—the most common enduro paceafter you’ve spent 10 minutes digging your bike out of the mud or stopped to change a spark plug or replace a broken throttle cable. If you’ve had trouble, you’ll have to gas it when you get going again, passing every rider you catch up to for awhile, even on tight trails, and really dialing it on when you come to a clear stretch of fire road or two-track lane.

To get this speed and to get through the obstacles without delay, you need a motorcycle with good power, correct gearing and superior handling. As a rider, it helps to have natural agility combined with skills that often take years to acquire and master, mechanical know-how to set up your bike beforehand and to make adjustments and repairs during a run, and the stamina and willpower to keep going. And it’s easier and more fun if you have an experienced gas crew to fuel and feed you when you need it and find you when you’re broken down far out on the course.

Money is all you need to get the right motorcycle and to campaign it, but the riding skill needed to do well, or even finish within the time limit, is acquired only by riding and more riding, practicing techniques and competing often and hard. New England Trail Rider Association, which has run enduros and enduro schools for several years, recommends its members have 3000 miles of trail-riding experience before entering an enduro for the first time. It’s the best way to learn to read a strange trail quickly and to negotiate unfamiliar obstacles.

Scoring an enduro is a lot like a sports car rally—each rider starts out with 1000 points and is penalized for being early or late at each of a series of checkpoints along the marked route, usually at places unknown to the riders. You try to maintain the pre-announced average speed or speeds for the run, a near impossible goal even at the 24 mph pace used in most events, because the penalties for straying from this schedule are severe. Under AMA rules, you get two points off for the first minute early at a check, five for each additional minute early, and one point for ea'ch minute late. If you’re more than 15 minutes early or an hour late at any checkpoint you're disqualified. Ties are broken at a special check, where seconds in addition to minutes are counted. >

Hitting checkpoints accurately is no accident. Every serious rider has a resetable speedometer, one or two watches, a routeholder to display information about time and distance to each turn of the course. Some riders have specialized, more sophisticated devices designed to eliminate the need for making calculations while you’re riding at top speed on difficult trails.

The best motorcycle piloted by the best rider will not even finish an endurance run unless the bike is properly prepared beforehand and enough tools and spare parts are carried to make repairs in the field. An enduro is not only a test of your endurance, but that of your machine, and every run is laid out with both in mind. Butt-bruising bumps in endless succession, deep sand, mud and water, rocks, logs, tangled underbrush—all try to tear you and your motorcycle apart.

Knowing this, it’s surprising that unless you’re a beginner you’re not nervous as you line up at the start and wait for your minute to come up. You’ve prepared for this moment, and you’re looking forward to the ride. Breakdowns during previous enduros are far from your mind. Perhaps the nightmare of a giant bog or unclimbable hill may linger, but more likely you’re thinking of ways to get into the groove quickly, to keep your speed on the twisting, tree-lined trail.

By the time you reach noon gas, about halfway through the day’s run, both you and your motorcycle are sure to need refueling. As your pit crew tends to the bike, you down some Gatorade or water and take a few quick bites of high-energy food—maybe a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, candy or concentrated food sticks. If there’s a half-hour or one-hour layover and you’re not running late you can rest, but most riders find they have to hurry—they need those minutes to get back on schedule.

Not every rider makes it to the finish, even on a fairly easy run, no matter how well prepared. A lost gas crew can cause you to run out of fuel and leave you stranded miles from the nearest road. A thrown chain may spoil your day. A hidden stump or unyielding tree might send you to the hospital, even though serious injuries are pretty rare.

What is the lure of motorcycle enduro riding? What keeps all kinds of ordinary, intelligent, fun-loving people coming back for more of this seemingly senseless punishment where there’s hardly a handful of spectators to witness the toughest tests?

The challenge and fun, of difficult, endlessly different riding, and of playing an interesting and often thrilling motosport game. And think a minute—where else can anybody, male or female, young or old compete directly against the best in the country without first having to qualify or make a team ôr work up through eliminations?

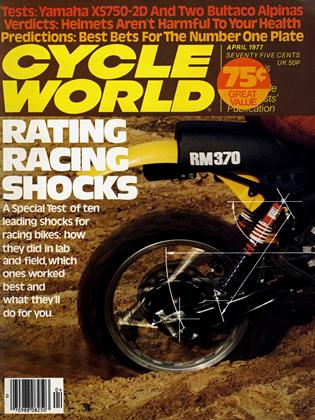

Any of us can challenge the top athletes in any sport. But unless we’ve already proved we’re in their league we'll never get the chance to meet them face to face at their own game. Yet anyone can challenge Dick Burleson, the Pentons, Bill Kain or any of the other champion enduro riders just by entering the same events. It’s one of a handful of sports where you get this chance.

Strangely, at the end of an enduro no cheers ring out: no one’s openly elated by victory or dejected in defeat. Those who make it are happy. Those who fail have new stories to tell and hopes of a better run next time. And if the weather’s been good almost everyone thinks it was fun.

It may be hours before the scores are tabulated and the winners known. By then the crowded campground will be thinning, and many of the riders and their crews— wives, friends and children—will be on the road home. The ones who stay late are the ones who think they have a chance of taking home some gold. Those who trophy get the best kind of applause—from the riders who fought hardest to keep them from winning.

Once you’ve got some trail-riding experience and a bike that wants to take you where you've never been before, you start looking for new and challenging places to go and new tests of your increasing skill and confidence. And if finding hassle-free riding areas is a problem and the idea of competition appeals to you, you’ll decide to try an enduro.

But how do you get started? Unless you've got friends in the sport, are a member of a trail-riding club or know an enduro-oriented motorcycle dealer, you may have a tough time learning how to go about it. In fact you’ll feel like you’re riding at night without a headlight—you won’t know what to expect.

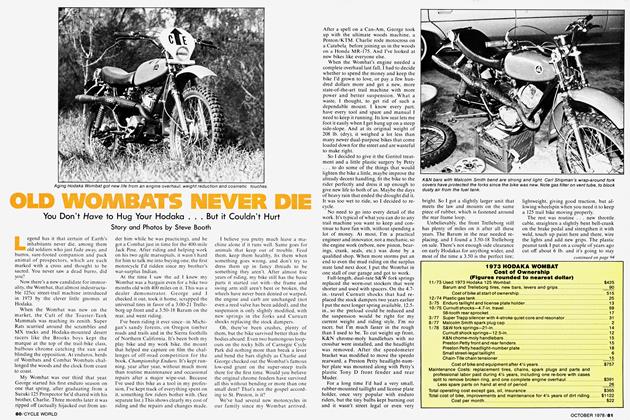

That’s the way it was a few years ago when my son George and I showed up one foggy morning for the Deford 100, his first enduro. I was there to gas him up during the run and to give him moral support along the way. We’d had a hard time finding this enduro, and when he signed up a little after 7 a.m. we were still in the dark. What’s the sheet with all the numbers on it? How do you know when you start? Where’s the starting line? Why do> you need a driver’s license if an enduro is run on trails? These are some of the questions every beginner asks.

There was a time, not too long ago, when almost anyone who showed up at an enduro with a bike could ride. Not any more. In response to pressure from law enforcement agencies, environmental groups and disturbed citizens, the AMA and many sponsoring clubs have tightened the requirements for entry.

To ride most enduros you’ll need a current AMA competition membership card and a valid driver’s license. In New England you’ll have to be a member of the New England Trail Rider Association to enter that organization’s endurance runs, and you’ll have to attend enduro school first if you’re a beginner. Your bike must be licensed for street use, and the plate should be mounted on the bike. Carry the registration with you during an event. The bike should also have a number plate, working headlight and taillight and a silencer-spark arrestor that meet AMA and U.S. Forestry Service requirements. Some enduros, particularly the nationals, even require a brake light, horn and rear-view mirror. In the west, a Forestry Servicelegal bike may be all you need. In any case, find out what you’ll need ahead of time and be prepared to comply or not run.

Before you get upset at all this red tape and weighty equipment you’d just as soon forget, take another look at the requirements—they all make sense. Part of the enduro may be run on public roads where operator and vehicle laws prevail, and much of the rest is in the boonies where fire is a real danger. And why should residents of those normally quiet lands be jarred by hundreds of noisy machines on trails they give permission to use? Unnecessary noise is a fast way to end the whole sport of trail and enduro riding.

What else do you need? Just some riding clothes, a few spare parts and tools and someone to run gas for you. And most important of all—the urge to finish!

For your first enduro, try to find one not too far away and not over 100 miles long. Check with dealers of enduro bikes in your area for the schedule of upcoming enduros. One of them is sure to know because he’ll have riders there.

Avoid national championship enduros at first. They’re tough. The whole atmosphere is more serious, and a lot of the fun is missing. What you really want is a wellestablished, well-run local enduro, one other riders recommend because they enjoyed the last event there.

Sign up the afternoon before if you can; you’ll have a chance to talk to other riders and look at their machines. And if you don’t understand something about the event you’ll find plenty of riders anxious to help you. If you’re a little nervous, check over your bike again or do what all the other nervous riders seem to do—take your bike out on some of the nearby trails to get the feel of them.

When you fill out the entry blank you’ll put the engine class of your bike and the letter ‘A’ or ‘B’ depending on your enduro expertise. ‘A’ is for experts, so as a beginner you’ll write kB’ unless there is also a ‘C’ classification. Then sign your name. Minors will also need the signature of a parent or guardian.

After you've completed the entry blank, you'll probably draw your riding number out of a box, and you'll receive a printed route sheet of mileages to each turn on the course. Often you'll also get a scorecard to wear around your neck or carry with you in a jacket pocket or container on your bike. This is used to keep track of your time and score on the run, and it’s your responsibility to keep it dry and legible and not to lose it. If you don’t get a scorecard, it means you’ll receive checks marked with your time as you pass through each checkpoint.

continued on page 100

continued from page 63

Enduro rules and the techniques of timekeeping will be very important later, although even beginners should have an idea of what they’re all about. Read the AMA Amateur Rule Book and talk to other riders. But on your first enduro the chances of getting ahead of schedule are very slight. You’ll have enough trouble keeping your bike going and trying not to be so late you’ll be disqualified.

The route sheet always consists of columns of letters designating turn directions—L for left, RR for a right followed immediately by a second right, etc.—and numbers indicating actual cumulative mileage to each turn on the course, and to gas stops, as measured by the organizer. Each turn is numbered consecutively and the turn arrows on the course will usually be identified with these numbers. This information is enough to keep you from getting lost if some arrows are missing, and it gives you an idea when to expect the next arrow. But the route sheet is not really complete without notations of the elapsed time at which you should reach each turn if you maintain the average speed or speeds announced as being used in the enduro. Occasionally these times are printed right on the route sheet, but most often you'll find only white space to the right of each column of mileages. Then it’s up to you to write in the times in minutes and seconds.

If you don’t have a time-distance table (you usually get one when you buy a route sheet holder) you'll have to do a lot of arithmetic to get the route times. It’s worth the price of a route sheet holder to get a table.

No need to write the time to every turn on the route sheet unless you want to—you probably won’t look at it very much while you're an enduro novice anyhow. But when writing in the elapsed times be sure to start from zero again after the noon gas stop if the mileage leaving there starts at zero, as it often does when the course is laid out in a morning and afternoon loop from headquarters.

continued on page 116

continued from page 101

Once you’ve written down the elapsed times, cut the sheet into strips and tape them end-to-end in sequence, then roll them into a route sheet holder fastened to the handlebars of your bike. If you don’t have a holder you can tape the route sheet to your gas tank, but unless you completely cover it with plastic sheet or clear tape don’t expect it to be readable very long, especially if the weather's wet or the trail is muddy.

The number you've drawn tells your starting position in minutes after key time, the start of the enduro. If key time is 10:00 a.m., the first riders, those with numbers like 1-A, 1-B. 1-C or 101. 201. 301. would leave the line at exactly 10:01. Numbering systems vary, but if you draw 15 or 215 or 15-B you'll start 15 minutes after key time with several other riders.

Confusing? You'd better believe it.

The morning of the event dress for the weather and try to eat a normal breakfast so you won't get hungry before noon gas. Fire up your bike and get it warm if you think that’s a good idea, and maybe ride it a bit to smooth it out. Then top it off with gas and make sure everything else is set. Line up well before the start so you won’t be late. This will give time to set your odometer to zero and let you set your watch accurately as the riders ahead of you leave. Set it so you’ll start at exactly 12:00 on your watch no matter what time it really is. Then it will correspond with the elapsed times you put on your route sheet and the key times posted at checkpoints.

At the signal to go, get away quickly. Often enduros begin with a dead-engine start, and this separates the riders a bit right away. There are seldom more than five of you on a minute, so it’s not much of a problem.

If there are riders right in front of you, you’ll have a tendency to follow them. Follow the arrows instead, and ride fast where you can. The reason for not follow\ ing other riders blindly is that you might pick up a group of trail-bikers not part of the enduro. It’s happened. Use your brain as well as riding skill when you encounter obstacles. There’s more than one way to get to the top of a sandy hill or reach the other side of a bog! Just don’t bypass any checkpoints.

continued on page 118

continued from page 117

If the riding’s easy for awhile and you have a free hand, roll your route sheet ahead and try to use it. Each turn arrow should be numbered and have the mileage to that point on it. If you lose the trail, backtrack to the last arrow and read the mileage, then reset your odometer to this figure and follow the route sheet carefully until you pick up arrows again.

Probably the most important thing for a beginner to remember is to keep moving and don’t lose the course. Seconds spent standing still are hard to get back. If you have trouble you'll have to gas it to get back on schedule or avoid disqualification—remember. you’re out if you’re more than an hour late at any timed checkpoint. Often you get a layover at noon gas, which you can use to make up lost time. But if you fall too far back you should also know when to drop out if mechanical trouble, injury or certain disqualification makes finishing next to impossible.

One reassuring thing: If you break down or are hurt back in the boonies somewhere, you’ll get help. Other riders and their crews will assist you if you’re injured, and if your bike won’t run the pick-up crew riding the course after the last rider will find you and get both you and your machine back to headquarters if you haven’t already found a ride with someone’s gas crew or the people who’ve been manning a nearby checkpoint and are headed home.

And don’t get uptight if the trophies elude you for a while. Even if you’re a good rider they’re hard to come by. I§]