OLD WOMBATS NEVER DIE

You Don’t Have to Hug Your Hodaka . . . But it Couldn’t Hurt

Story and Photos by Steve Booth

Legend has it that certain of Earth’s inhabitants never die, among them old soldiers who just fade away, and burros, sure-footed companion and pack animal of prospectors, which are each marked with a cross and thought to be sacred. You never saw a dead burro, did you?

Now there’s a new candidate for immorality, the Wombat, that almost indestructable 125cc street-trail machine introduced in 1973 by the clever little gnomes at Hodaka.

When the Wombat was new on the market, the Cult of the Toaster-Tank Mammals was reaching its zenith. Super Rats scurried around the scrambles and MX tracks and Hodaka-mounted desert racers like the Brooks boys kept the marque at the top of the trail-bike class, bulbous chrome catching the sun and blinding the opposition. At enduros, herds of Wombats and Combat Wombats challenged the woods and the clock from coast to coast.

My Wombat was our third that year. George started his first enduro season on one that spring, after graduating from a Suzuki 125 Prospector he’d shared with his brother, Charlie. Three months later it was ripped ofif (actually hijacked out from under him while he was practicing), and he got a Combat just in time for the 400-mile Jack Pine. After riding and helping work on his two agile marsupials, it wasn’t hard for him to talk me into buying one, the first motorcycle I'd ridden since my brother’s war-surplus Indian.

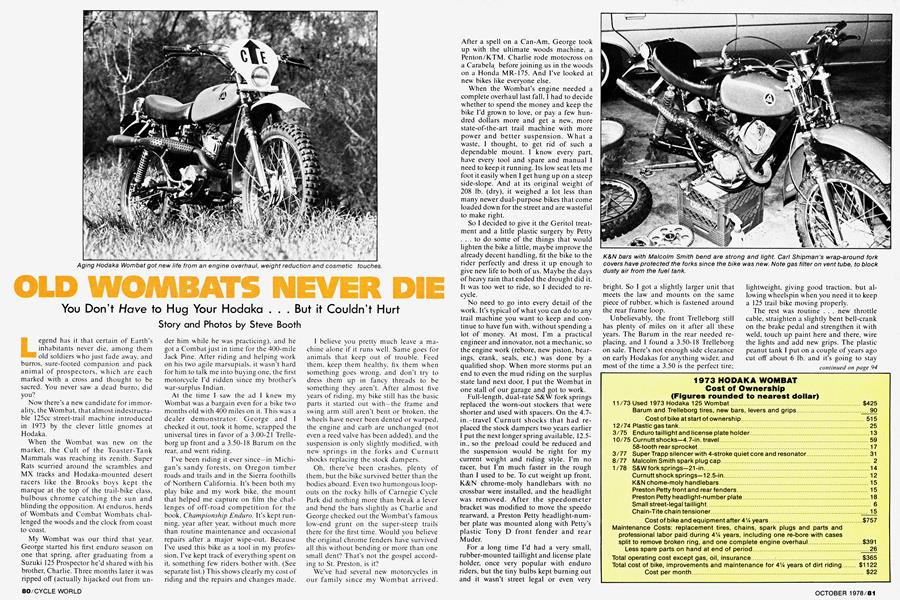

At the time I sawthe ad I knew my Wombat was a bargain even for a bike two months old with 400 miles on it. This was a dealer demonstrator. George and I checked it out, took it home, scrapped the universal tires in favor of a 3.00-21 Trelleborg up front and a 3.50-18 Barum on the rear, and went riding.

I’ve been riding it ever since—in Michigan’s sandy forests, on Oregon timber roads and trails and in the Sierra foothills of Northern California. It’s been both my play bike and my work bike, the mount that helped me capture on film the challenges of off-road competition for the book. Championship Enduro. It’s kept running, year after year, without much more than routine maintenance and occasional repairs after a major wipe-out. Because I’ve used this bike as a tool in my profession, I’ve kept track of everything spent on it, something few riders bother with. (See separate list.) This shows clearly my cost of riding and the repairs and changes made. I believe you pretty much leave a machine alone if it runs well. Same goes for animals that keep out of trouble. Feed them, keep them healthy, fix them when something goes wrong, and don't try to dress them up in fancy threads to be something they aren’t. After almost five years of riding, my bike still has the basic parts it started out with—the frame and swing arm still aren’t bent or broken, the wheels have never been dented or warped, the engine and carb are unchanged (not even a reed valve has been added), and the suspension is only slightly modified, with new springs in the forks and Curnutt shocks replacing the stock dampers.

Oh, there’ve been crashes, plenty of them, but the bike survived better than the bodies aboard. Even two humongous loopouts on the rocky hills of Carnegie Cycle Park did nothing more than break a lever and bend the bars slightly as Charlie and George checked out the Wombat’s famous low-end grunt on the super-steep trails there for the first time. Would you believe the original chrome fenders have survived all this without bending or more than one small dent? That’s not the gospel according to St. Preston, is it?

We’ve had several new motorcycles in our family since my Wombat arrived. After a spell on a Can-Am, George took up with the ultimate woods machine, a Penton/KTM. Charlie rode motocross on a Carabela before joining us in the woods on a Honda MR-175. And I’ve looked at new bikes like everyone else.

When the Wombat’s engine needed a complete overhaul last fall, I had to decide whether to spend the money and keep the bike I’d grown to love, or pay a few hundred dollars more and get a new, more state-of-the-art trail machine with more power and better suspension. What a waste, I thought, to get rid of such a dependable mount. I know every part, have every tool and spare and manual I need to keep it running. Its low seat lets me foot it easily when I get hung up on a steep side-slope. And at its original weight of 208 lb. (dry), it weighed a lot less than many newer dual-purpose bikes that come loaded down for the street and are wasteful to make right.

So I decided to give it the Geritol treatment and a little plastic surgery by Petty ... to do some of the things that would lighten the bike a little, maybe improve the already decent handling, fit the bike to the rider perfectly and dress it up enough to give new life to both of us. Maybe the days of heavy rain that ended the drought did it. It was too wet to ride, so I decided to recycle.

No need to go into every detail of the work. It’s typical of what you can do to any trail machine you want to keep and continue to have fun with, without spending a lot of money. At most, I’m a practical engineer and innovator, not a mechanic, so the engine work (rebore, new piston, bearings, crank, seals, etc.) was done by a qualified shop. When more storms put an end to even the mud riding on the surplus state land next door, I put the Wombat in one stall of our garage and got to work.

Full-length, dual-rate S&W fork springs replaced the worn-out stockers that were shorter and used with spacers. On the 4.7in.-travel Curnutt shocks that had replaced the stock dampers two years earlier I put the next longer spring available, 12.5in., so the preload could be reduced and the suspension would be right for my current weight and riding style. I’m no racer, but I’m much faster in the rough than I used to be. To cut weight up front, K&N chrome-moly handlebars with no crossbar were installed, and the headlight was removed. After the speedometer bracket was modified to move the speedo rearward, a Preston Petty headlight-number plate was mounted along with Petty’s plastic Tony D front fender and rear Muder.

For a long time I’d had a very small, rubber-mounted taillight and license plate holder, once very popular with enduro riders, but the tiny bulbs kept burning out and it wasn’t street legal or even very bright. So I got a slightly larger unit that meets the law and mounts on the same piece of rubber, which is fastened around the rear frame loop.

Unbelievably, the front Trelleborg still has plenty of miles on it after all these years. The Barum in the rear needed replacing, and I found a 3.50-18 Trelleborg on sale. There’s not enough side clearance on early Hodakas for anything wider, and most of the time a 3.50 is the perfect tire;

lightweight, giving good traction, but allowing wheelspin when you need it to keep a 125 trail bike moving properly.

The rest was routine . . . new throttle cable, straighten a slightly bent bell-crank on the brake pedal and strengthen it with weld, touch up paint here and there, wire the lights and add new grips. The plastic peanut tank I put on a couple of years ago cut off about 6 lb. and it’s going to stay there unless I need a larger gas tank to extend my range. Because the bike uses premix, on long rides I carry a small plastic measuring bottle of 2-stroke oil so I can fill up at any gas station.

continued on page 94

$425

continued from page 81

I've used the same Uni unbreakable plastic clutch and front brake levers for a long time. They still survive and will remain right where they are. There's a Malcolm Smith spark plug cap instead of the original, to keep the engine firing when in water, since the Wombat already has a high-breathing air intake to its foam filter. A Chain-Tite tensioner ends the need for adjustments during a ride.

When I finished all this the Wombat looked leaner, and it is. Dry weight is just 199 lb. with battery and a complete set of tools, 9 lb. less than its weight when new, and 38.4 lb. less than the latest Hodaka Wombat. Ready to ride, with a full tank of gas. it weighs 215 lb. Not bad for a motorcycle with a steel frame and steel wheels.

What makes all this so unusual? Nothing much, except the challenge and fun of making a good, reliable trail bike a little better, making it run as far as you want to go for as long as you want to keep it. The basic Hodaka Wombat has a few jumps on other trail bikes to start. Not only is it an easy bike for the amateur mechanic to work on, the owner's manual has a complete illustrated parts list so finding what you need is easy. With the correct Hodaka part numbers you can even order by phone. The drawings help during reassembly, too. when you aren’t sure which part goes where.

And Pabatco is a friendly company, started by trail riders who answer questions and send you tips and technical specs whenever you ask. There’s a shop manual available to owners who want to do their own work and of course there’s that constant flow of good humor that helped build and hold the loyalty of Hodaka riders, even those who’ve gone on to more exotic machinery. Looking for accessory and racerelated items? Hodaka itself has lots more of them than most manufacturers, and there’s Tiger Distributing, 653 W. Broadway. Glendale, Calif. 91204, which carries Works Performance shocks, Swenco swing arms and other special parts for Hodakas. Charles Curnutt, 75992 Baseline, Twentynine Palms, Calif. 92277, has Curnutt shocks to fit.

But all this can't overshadow the fact that the original Wombat—even without the longer-travel suspension and other advanced features of the latest model—is fun to ride and ride and ride! And it gets you there. Remember big Frank Wheeler, who rode one 10,000 miles around the continent of Australia back in ’73? 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontYou Can't Take the Harley Out of the Boy

October 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Departments

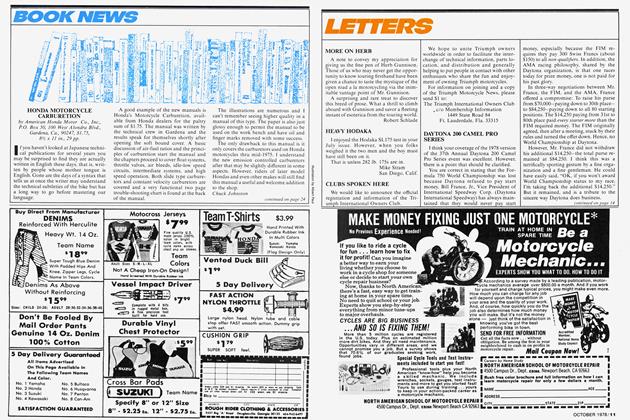

DepartmentsBook News

October 1978 By A.G., Chuck Johnston, Michael M. Griffin -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

October 1978 -

Short Strokes

October 1978 By Tim Barela -

Technical

TechnicalYamaha It250/400 Steering Fix

October 1978 By Len Vucci