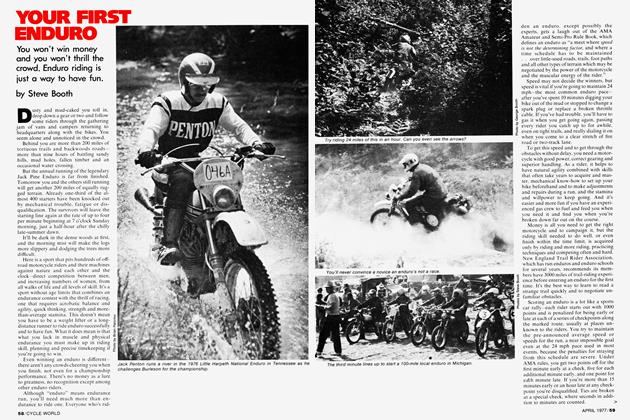

THE JACK PINE

Grandaddy of the Super Enduros

Steve Booth

Legendary Jack Pine. Kind of rings, like the cowbell that's been the per-petual overall trophy since the first 500-mile Michigan enduro of that name back in 1923. Every year since, except during World War II and in 1968 (cancelled due to outlaw biker trouble the year before at the overnight layover point), the Lansing Motorcycle Club has treated off-road motorcyclists to the ultimate challenge—two days of 24-mph misery and joy—seemingly endless stretches of deep sand alternating with brush-busting, bar-bending tight going through the pines and hardwoods of the northern half of Michigan’s lower peninsula, forests full of stumps and fallen logs, criss-crossed by creeks and rivers and filled with mudholes that bring instant recall to riders who spent wet, agonizing minutes there learning the meaning of "bogged down."

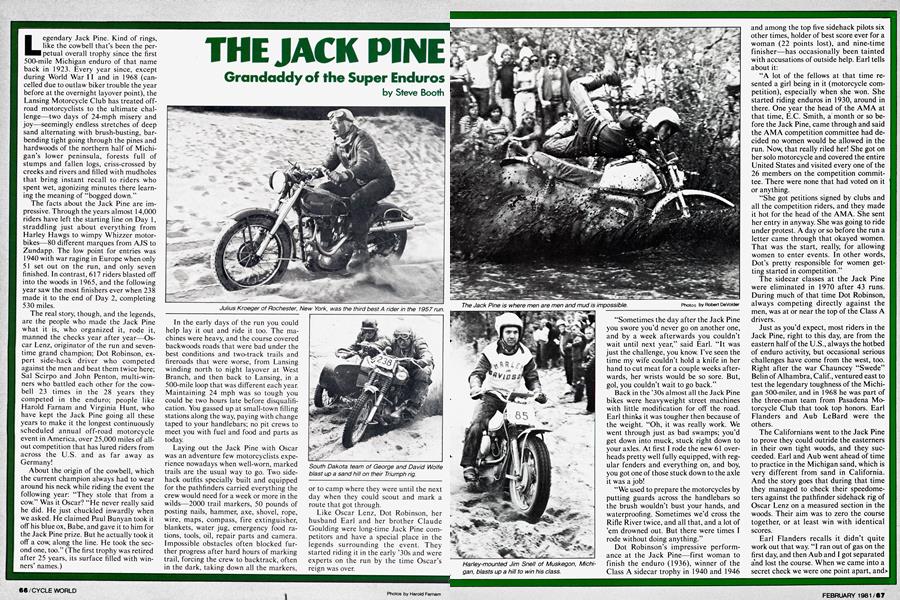

The facts about the Jack Pine are impressive. Through the years almost 14,000 riders have left the starting line on Day 1, straddling just about everything from Harley Hawgs to wimpy Whizzer motorbikes—80 different marques from AJS to Zundapp. The low point for entries was 1940 with war raging in Europe when only 51 set out on the run, and only seven finished. In contrast, 617 riders blasted off into the woods in 1965, and the following year saw the most finishers ever when 238 made it to the end of Day 2, completing 530 miles.

The real story, though, and the legends, are the people who made the Jack Pine what it is, who organized it, rode it, manned the checks year after year—Oscar Lenz, originator of the run and seventime grand champion; Dot Robinson, expert side-hack driver who competed against the men and beat them twice here; Sal Scirpo and John Penton, multi-winners who battled each other for the cowbell 23 times in the 28 years they competed in the enduro; people like Harold Farnam and Virginia Hunt, who have kept the Jack Pine going all these years to make it the longest continuously scheduled annual off-road motorcycle event in America, over 25,000 miles of allout competition that has lured riders from across the U.S. and as far away as Germany!

About the origin of the cowbell, which the current champion always had to wear around his neck while riding the event the following year: “They stole that from a cow.” Was it Oscar? “He never really said he did. He just chuckled inwardly when we asked. He claimed Paul Bunyan took it off his blue ox, Babe, and gave it to him for the Jack Pine prize. But he actually took it off a cow, along the line. He took the second one, too.” (The first trophy was retired after 25 years, its surface filled with winners’ names.)

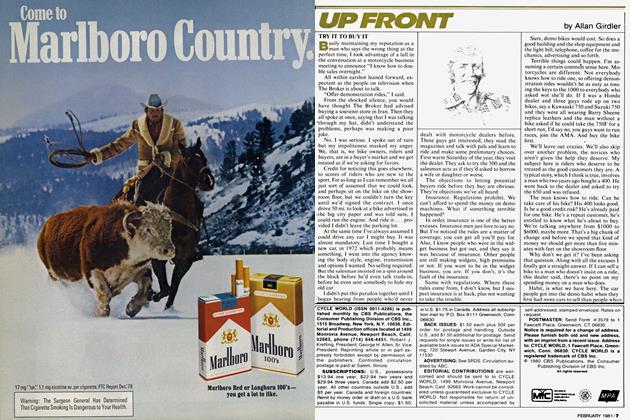

In the early days of the run you could help lay it out and ride it too. The machines were heavy, and the course covered backwoods roads that were bad under the best conditions and two-track trails and fireroads that were worse, from Lansing winding north to night layover at West Branch, and then back to Lansing, in a 500-mile loop that was different each year. Maintaining 24 mph was so tough you could be two hours late before disqualification. You gassed up at small-town filling stations along the way, paying with change taped to your handlebars; no pit crews to meet you with fuel and food and parts as today.

Laying out the Jack Pine with Oscar was an adventure few motorcyclists experience nowadays when well-worn, marked trails are the usual way to go. Two sidehack outfits specially built and equipped for the pathfinders carried everything the crew would need for a week or more in the wilds—2000 trail markers, 50 pounds of posting nails, hammer, axe, shovel, rope, wire, maps, compass, fire extinguisher, blankets, water jug, emergency food rations, tools, oil, repair parts and camera. Impossible obstacles often blocked further progress after hard hours of marking trail, forcing the crew to backtrack, often in the dark, taking down all the markers,

or to camp where they were until the next day when they could scout and mark a route that got through.

Like Oscar Lenz, Dot Robinson, her husband Earl and her brother Claude Goulding were long-time Jack Pine competitors and have a special place in the legends surrounding the event. They started riding it in the early ’30s and were experts on the run by the time Oscar’s reign was over.

“Sometimes the day after the Jack Pine you swore you’d never go on another one, and by a week afterwards you couldn’t wait until next year,” said Earl. “It was just the challenge, you know. I’ve seen the time my wife couldn’t hold a knife in her hand to cut meat for a couple weeks afterwards, her wrists would be so sore. But, gol, you couldn’t wait to go back.”

Back in the ’30s almost all the Jack Pine bikes were heavyweight street machines with little modification for off the road. Earl thinks it was tougher then because of the weight. “Oh, it was really work. We went through just as bad swamps; you’d get down into muck, stuck right down to your axles. At first I rode the new 61 overheads pretty well fully equipped, with regular fenders and everything on, and boy, you got one of those stuck down to the axle it was a job!

“We used to prepare the motorcycles by putting guards across the handlebars so the brush wouldn’t bust your hands, and waterproofing. Sometimes we’d cross the Rifle River twice, and all that, and a lot of ’em drowned out. But there were times I rode without doing anything.”

Dot Robinson’s impressive performance at the Jack Pine—first woman to finish the enduro (1936), winner of the Class A sidecar trophy in 1940 and 1946 and among the top five sidehack pilots six other times, holder of best score ever for a woman (22 points lost), and nine-time finisher—has occasionally been tainted with accusations of outside help. Earl tells about it:

“A lot of the fellows at that time resented a girl being in it (motorcycle competition), especially when she won. She started riding enduros in 1930, around in there. One year the head of the AMA at that time, EC. Smith, a month or so before the Jack Pine, came through and said the AMA competition committee had decided no women would be allowed in the run. Now, that really riled her! She got on her solo motorcycle and covered the entire United States and visited every one of the 26 members on the competition committee. There were none that had voted on it or anything.

“She got petitions signed by clubs and all the competition riders, and they made it hot for the head of the AMA. She sent her entry in anyway. She was going to ride under protest. A day or so before the run a letter came through that okayed women. That was the start, really, for allowing women to enter events. In other words, Dot’s pretty responsible for women getting started in competition.”

The sidecar classes at the Jack Pine were eliminated in 1970 after 43 runs. During much of that time Dot Robinson, always competing directly against the men, was at or near the top of the Class A drivers.

Just as you’d expect, most riders in the Jack Pine, right to this day, are from the eastern half of the U.S., always the hotbed of enduro activity, but occasional serious challenges have come from the west, too. Right after the war Chauncey “Swede” Belin of Alhambra, Calif., ventured east to test the legendary toughness of the Michigan 500-miler, and in 1968 he was part of the three-man team from Pasadena Motorcycle Club that took top honors. Earl Flanders and Aub LeBard were the others.

The Californians went to the Jack Pine to prove they could outride the easterners in their own tight woods, and they succeeded. Earl and Aub went ahead of time to practice in the Michigan sand, which is very different from sand in California. And the story goes that during that time they managed to check their speedometers against the pathfinder sidehack rig of Oscar Lenz on a measured section in the woods. Their aim was to zero the course together, or at least win with identical scores.

Earl Flanders recalls it didn’t quite work out that way. “I ran out of gas on the first day, and then Aub and I got separated a*nd lost the course. When we came into a secret check we were one point apart, and> we didn’t know that. The rest of the time we were always together-—we tried to zero everything together, you know—but we didn’t know we were separated by one point.”

No matter. They made an impressive showing and proved their point. Despite the brush and stumps that caused them trouble, Earl rode his AJS to the grand championship with a score of 54 points lost, while Aub took the B Solo trophy on a BSA with the second best score, one point back. Swede Belin won Class A Sidecar with Howard Weakley in the Harley hack.

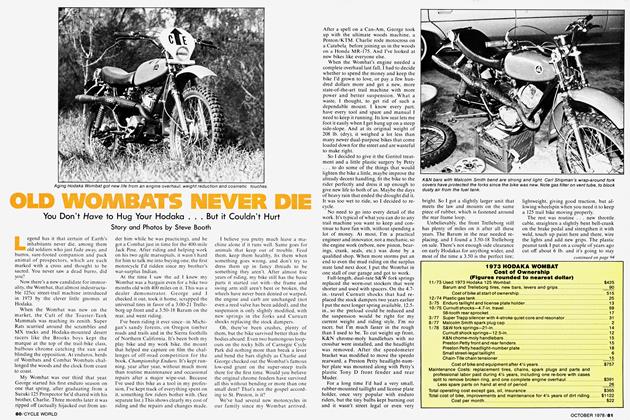

Out of 32 riders who have captured the cowbell for winning the Jack Pine prior to 1980, John Penton of Lorain, Ohio, is one of the only three men to take the top prize more than twice. He rode an NSU to victory in 1958 and 1960, then piloted a Husqvarna to become grand champion two more times, in ’66 and ’69. Only “Mr. Jack Pine,” himself, Oscar Lenz, with seven, and his Michigan arch-rival from the ’20s and ’30s, Dan Raymond, with five (they tied each other in 1932), claimed the cowbell more times. It wasn’t easy. In 28 years from 1948 through 1976 John missed only three Jack Pine enduros.

John Penton plainly loves the Jack Pine, so much that when he brought out his own enduro bikes in 1968, the 125cc model had the name Jackpiner lettered on the dark green tank. Twenty-five times he came back to challenge the Michigan woods and sand and to face off against the likes of winners Sal Scirpo, Gerry McGovern and Frank Piasecki, and seven-time national enduro champion Bill Baird. And to beat the punk kids, who each year came to beat the old men and the terrain, or at least to learn how.

A Penton rider never did win the big one at the Jack Pine, though. Papa John deserted his own brand in 1969 to ride a Husky to his fourth grand championship, beating out Penton-mounted Class A champion Bud Green by five points. In ’74 it was closer—Art Blough of Lansing, Mich., using rear wheel changes at noon gas each day to give him fresh rubber and super traction, squeezed his 250 Penton to within three points of the cowbell winner, Jim Fortune on a Husky. Again in 1977, last year the marque was produced, Penton rider Victor Ely of Columbus, Ohio, an open expert, came just as close, scoring 14 points off to the 11 that got Husqvarna pilot Dave Lipovsky his second Jack Pine win.

The 10-year battle between Husqvarna and Penton at the Jack Pine was over, and the Swede came out unscathed. Husky riders had won the event overall nine years straight. In 1968, of course, Illinois enduro ace Bill Baird Triumphed over both in the last four-stroke Jack Pine victory. But although the top prize so well fought for

eluded the Penton faithful, they edged out the Husky squad 38 to 35 in major Jack Pine trophies taken during the decade. A year later, in 1978, KTM, the Austrian cousin of the Penton motorcycle, finally rang the cowbell in Husky’s ears as firstyear A rider Bill Catron of Michigan took the prize, and Lipovsky placed second, on a KTM this time. The former Penton crew at KTM America, many of them Jack Pine riders of years gone by, must have celebrated when they heard the news.

But where had Husqvarna’s own Dick Burleson been during all of this? Mostly out seeking ISDT gold. You see, the Six Days and the Jack Pine were in conflict with early September dates until last year, when the traditional Labor Day weekend scheduling of the Jack Pine was moved ahead to mid-August. King Richard rode the enduro on a small-bore Penton back in the early ’70s, but dropped out after a first-day crash left him with a non-swiveling head he thought might be serious. In 1976 he took fifth in class with a respectable 28 points lost. When he endoed his Husky at high speed in 1979 after hitting a small log while trying to make up time, he hurt his neck and shoulders and had to drop out again.

But during all those years he won the national enduro championship six consecutive times without the help of the double points the two-day Jack Pine paid. And, of course, while his Husqvarna teammate Bob Popiel was piloting the 360 and 390 automatics to cowbell wins, Dick was bringing home gold medals from the ISDT each September.

Now the Jack Pine, though still one of the premier enduro events on the schedule for the national championship, has come to the end of an era that started 57 years ago. In 1980, for the first time, the Cowbell Classic was a one-day run, an enduro of only 200 mi.

Still not a relaxed Sunday trail ride, is it? But gone is the pain of picking up your tired and aching body at dawn on the second day and forcing it onto a motorcycle while the biting chill of the Michigan woods is still in the air, to punish it for another eight or nine hours of what you barely survived the day before. SI

View Full Issue

View Full Issue