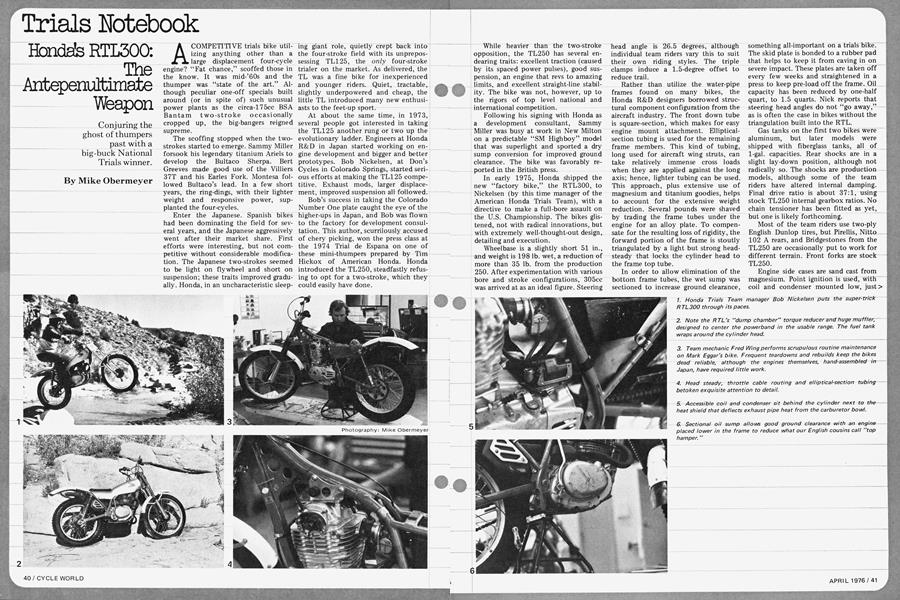

Trials Notebook

Honda's RTL300: The Antepenultimate Weapon

Conjuring the ghost of thumpers past with a big-buck National Trials winner.

Mike Obermeyer

A COMPETITIVE trials bike utilizing anything other than a large displacement four-cycle engine? “Fat chance,” scoffed those in the know. It was mid-’60s and the thumper was “state of the art.” Although peculiar one-off specials built around (or in spite of) such unusual power plants as the circa-175cc BSA Bantam two-stroke occasionally cropped up, the big-bangers reigned supreme.

The scoffing stopped when the twostrokes started to emerge. Sammy Miller forsook his legendary titanium Ariels to develop the Bultaco Sherpa. Bert Greeves made good use of the Villiers 37T and his Earles Fork. Montesa followed Bultaco’s lead. In a few short years, the ring-dings, with their lighter weight and responsive power, supplanted the four-cycles.

Enter the Japanese. Spanish bikes had been dominating the field for several years, and the Japanese aggressively went after their market share. First efforts were interesting, but not competitive without considerable modification. The Japanese two-strokes seemed to be light on flywheel and short on suspension; these traits improved gradually. Honda, in an uncharacteristic sleep-

ing giant role, quietly crept back into the four-stroke field with its unprepossessing TL125, the only four-stroke trialer on the market. As delivered, the TL was a fine bike for inexperienced and younger riders. Quiet, tractable, slightly underpowered and cheap, the little TL introduced many new enthusiasts to the feet-up sport.

At about the same time, in 1973, several people got interested in taking the TL125 another rung or two up the evolutionary ladder. Engineers at Honda R&D in Japan started working on engine development and bigger and better prototypes. Bob Nickelsen, at Don’s Cycles in Colorado Springs, started serious efforts at making the TL125 competitive. Exhaust mods, larger displacement, improved suspension all followed.

Bob’s success in taking the Colorado Number One plate caught the eye of the higher-ups in Japan, and Bob was flown to the factory for development consultation. This author, scurrilously accused of chery picking, won the press class at the 1974 Trial de España on one of these mini-thumpers prepared by Tim Hickox of American Honda. Honda introduced the TL250, steadfastly refusing to opt for a two-stroke, which they could easily have done.

While heavier than the two-stroke opposition, the TL250 has several endearing traits: excellent traction (caused by its spaced power pulses), good suspension, an engine that revs to amazing limits, and excellent straight-line stability. The bike was not, however, up to the rigors of top level national and international competition.

Following his signing with Honda as a development consultant, Sammy Miller was busy at work in New Milton on a predictable “SM Highboy” model that was superlight and sported a dry sump conversion for improved ground clearance. The bike was favorably reported in the British press. -

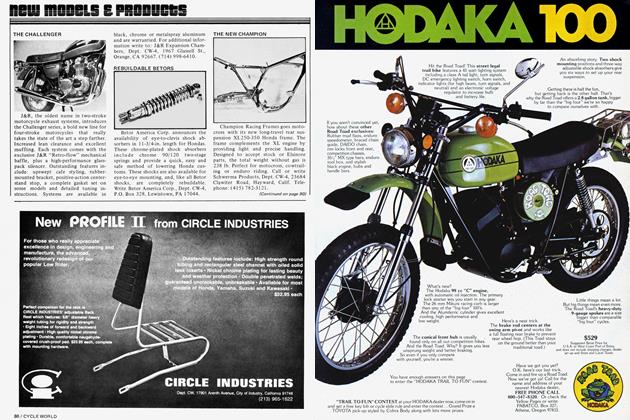

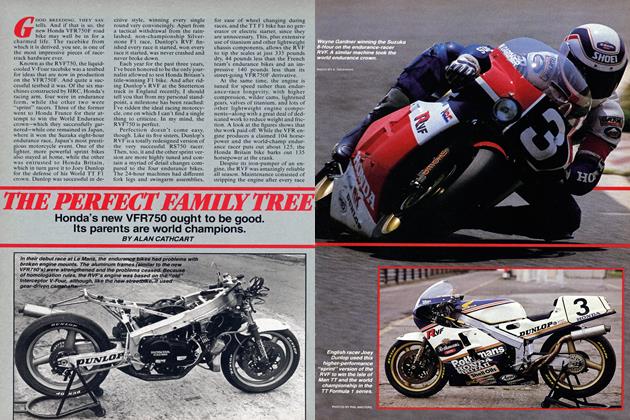

In early 1975, Honda shipped the new “factory bike,” the RTL300, to Nickelsen (by this time manager of the American Honda Trials Team), with a directive to make a full-bore assault on the U.S. Championship. The bikes glistened, not with radical innovations, but with extremely well-thought-out design, detailing and execution.

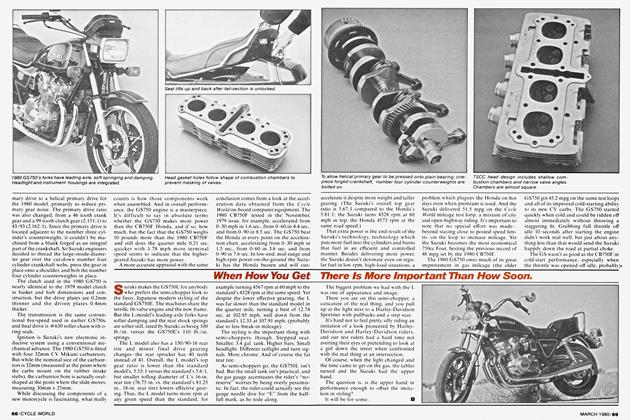

Wheelbase is a slightly short 51 in., and weight is 198 lb. wet, a reduction of more than 35 lb. from the production 250. After experimentation with various bore and stroke configurations, 305cc was arrived at as an ideal figure. Steering head angle is 26.5 degrees, although individual team riders vary this to suit their own riding styles. The triple clamps induce a 1.5-degree offset to reduce trail.

Rather than utilize the water-pipe frames found on many bikes, the Honda R&D designers borrowed structural component configuration from the aircraft industry. The front down tube is square-section, which makes for easy engine mount attachment. Ellipticalsection tubing is used for the remaining frame members. This kind of tubing, long used for aircraft wing struts, can take relatively immense cross loads when they are applied against the long axis; hence, lighter tubing can be used. This approach, plus extensive use of magnesium and titanium goodies, helps to account for the extensive weight reduction. Several pounds were shaved by trading the frame tubes under the engine for an alloy plate. To compensate for the resulting loss of rigidity, the forward portion of the frame is stoutly triangulated by a light but strong headsteady that locks the cylinder head to the frame top tube.

In order to allow elimination of the bottom frame tubes, the wet sump was sectioned to increase ground clearance, something all-important on a trials bike. The skid plate is bonded to a rubber pad that helps to keep it from caving in on severe impact. These plates are taken off every few weeks and straightened in a press to keep pre-load off the frame. Oil capacity has been reduced by one-half quart, to 1.5 quarts. Nick reports that steering head angles do not “go away,” as is often the case in bikes without the triangulation built into the RTL.

Gas tanks on the first two bikes were aluminum, but later models were shipped with fiberglass tanks, all of 1-gal. capacities. Rear shocks are in a slight lay-down position, although not radically so. The shocks are production models, although some of the team riders have altered internal damping. Final drive ratio is about 37:1, using stock TL250 internal gearbox ratios. No chain tensioner has been fitted as yet, but one is likely forthcoming.

Most of the team riders use two-ply English Dunlop tires, but Pirellis, Nitto 102 A rears, and Bridgestones from the TL250 are occasionally put to work for different terrain. Front forks are stock TL250.

Engine side cases are sand cast from magnesium. Point ignition is used, with coil and condenser mounted low, just> behind the cylinder. Flywheel weight has been increased to compensate for the higher displacement. Renthal bars are mounted, and can usually incur four or five months of heavy practice.

Carburetion has been the only real problem on the RTLs. Current choke size is 20mm, to avoid the “spit-back” problem encountered with large fourstrokes. This size is obviously somewhat restrictive of potential top-end performance, although no one who has seen one of these red and white tigers scream up a hill would worry about it too much. Nick talks guardedly about progressive carburetion, but this is still in the “dream” stage. Any R&D facility that can produce a hydraulically driven trials prototype presumably will not blanch at actually building one when it appears needful.

Heat from the tucked-in exhaust system was a problem early in the ’75 season, but an alloy heat-sink-cumshield devised by mechanic Fred Wing has totally alleviated such problems; carburetor boiling is now non-existent.

Riding the RTL is an experience. It is quite strong and quick, and definitely does not drive itself. It is designed to be ridden by experts, and can do amazing things in the hands of a top-notch rider. It will get a turkey in trouble. Compression braking is especially noticeable on throttle roll-off in first gear. Second! gear lessens the problem, and seems to be a more comfortable gear for the average rider. Torque, even in second, is tractor-like, and the bike’s extreme rev range makes hillclimbing a breeze.

When Nick turned me loose on it for a half-hour of rock-picking, he left me very relaxed: “Go ahead and push it. Don’t worry, it’s one of only six in existence. . . ”

The next production bike? Nick can’t, or won’t, say. In response to my query, he took me into the store room in Gardena and pulled out his first TL250 prototype, reported here some months back, and set it side by side with a current production TL250. Differences were almost negligible. “You figure it out,” he smiled.___

The inference seems clear. When Honda sends a prototype or prototypes for testing and development, taking the U.S. Championship and three places in the, top five in the process, they are unlikely to market a production version substantially different from the proven winner.

The RTL300 may not be the ultimate weapon; obviously nothing ever is. But Honda has produced a formidable challenger for top honors among trials bike manufacturers. If you can ever talk your way into a ride on one, do it! I guarantee it’ll blow you away! Otherwise, wait like the rest of us, with ’bated breath, for the arrival of the production bikes. Zowie! EB