The Crash Of The Big Green Wave

Sam Moses

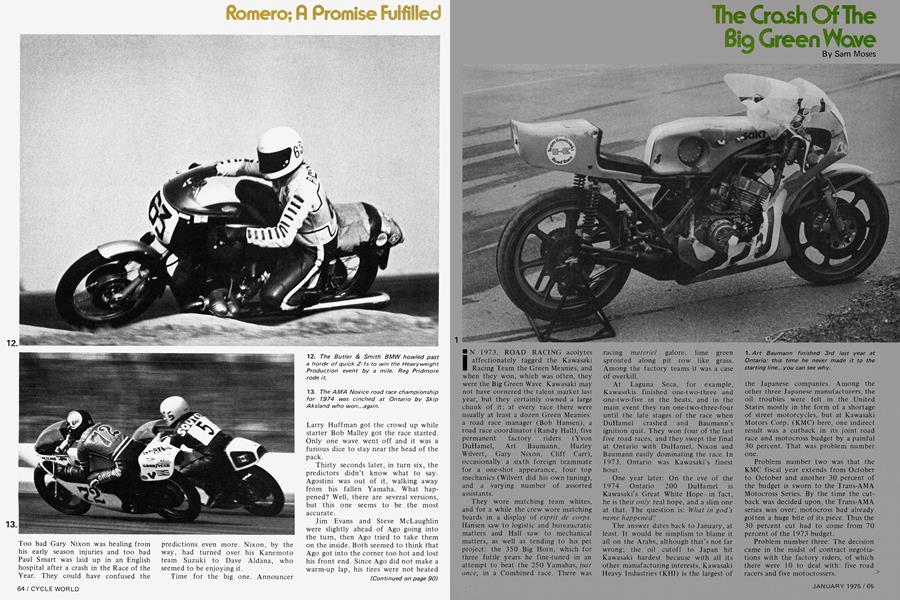

IN 1973, ROAD RACING acolytes affectionately tagged the Kawasaki Racing Team the Green Meanies, and when they won, which was often, they were the Big Green Wave. Kawasaki may not have cornered the talent market last year, but they certainly owned a large chunk of it; at every race there were usually at least a dozen Green Meanies: a road race manager (Bob Hansen), a road race coordinator (Randy Hall), five permanent factory riders (Yvon DuHamel, Art Baumann, Hurley Wilvert, Gary Nixon, Cliff Carr), occasionally a sixth foreign teammate for a one-shot appearance, four top mechanics (Wilvert did his own tuning), and a varying number of assorted assistants.

They wore matching team whites, and for a while the crew wore matching beards in a display of esprit de corps. Hansen saw to logistic and bureaucratic matters and Hall saw to mechanical matters, as well as tending to his pet project; the 350 Big Horn, which for three futile years he fine-tuned in an attempt to beat the 250 Yamahas, just once, in a Combined race. There was racing materiel galore; lime green sprouted along pit row like grass. Among the factory teams it was a case of overkill.

At Laguna Seca, for example, Kawasakis finished one-two-three and one-two-five in the heats, and in the main event they ran one-two-three-four until the late stages of the race when DuHamel crashed and Baumann's ignition quit. They won four of the last five road races, and they swept the final at Ontario with DuHamel, Nixon and Baumann easily dominating the race. In 1973, Ontario was Kawasaki’s finest hour.

One year later: On the eve of the 1974 Ontario 200 DuHamel is Kawasaki's Great White Hope--in fact, he is their oiilj' real hope, and a slim one at that. The question is: What in god's name hap pened'

The answer dates back to January, at least. It would be simplism to blame it all on the Arabs, although that’s not far wrong; the oil cutoff to Japan hit Kawasaki hardest because with all its other manufacturing interests, Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI) is the largest of

the Japanese companies. Among the other three Japanese manufacturers, the oil troubles were felt in the United States mostly in the form of a shortage of street motorcycles, but at Kawasaki Motors Corp. (KMC) here, one indirect result was a cutback in its joint road race and motocross budget by a painful 30 percent. That was problem number one.

Problem number two was that the KMC fiscal year extends from October to October and another 30 percent of the budget is sworn to the Trans-AM A Motocross Series. By the time the cutback was decided upon, the Trans-AMA series was over; motocross had already gotten a huge bite of its piece. Thus the 30 percent cut had to come from 70 percent of the I 973 budget.

Problem number three: The decision came in the midst of contract negotiations with the factory riders, of which there were 10 to deal with: five road racers and five motocrossers.

Number four; DuHamel was asking for a raise (as was motocross star Jim Weinert), and had a 1973 win at Ontario as ammunition for his case. He figured he was worth about $10,000 a race for the six National road races in 1974. Kawasaki agreed with him.

The exact figures of the racing budget are a closely-guarded secret, but the cut has been officially estimated at an easy $100,000; at 30 percent, that would make the original budget in the neighborhood of a third of a million dollars. So take $330,000, more or less, subtract $100,000 for the Trans-AMA, $100,000 for the budget cut, and $60,000 or so for DuHamel. That leaves about $70,000. Figure most of that to Weinert, and that barely leaves gas money with which to operate two teams for an entire season, including salaries and traveling expenses.

Then take the Yamaha TZ700 and the new Suzuki 750 road racers, and the problem compounds. Add the near-zero development of the Kawasaki 750 H2R over the winter, and what you have is one horsepower-obsolescent road race machine ridden by a rider with no team of any consequence to support him, a combination that virtually guarantees a no-show in Victory Circle. From a royal flush in 1973 to an ace-high nothing in 1974. For starters, that’s what in god’s name happened.

But Kawasaki was smart enough to realize the obvious potential disaster in

such a situation; so now for the solutions, which unfortunately were far fewer than the problems. One: The bikes and spare parts come free from KHI, so the expense to KMC there was zero.

Two: Bob Hansen. Although he

knew he was on the way out as a victim of the low-budget shuffle, because he had worked for three years to put Kawasaki where it had been after Ontario last year he wasn’t going to sit idle and passively watch the crash. So he got in a couple of lame-duck licks, namely convincing Kawasaki that they needed Baumann and Wilvert.

Baumann got the exact financial deal he had had in 1973. and Wilvert got sort of a factory ride: a bike and parts. No salary, no start money, no mechanic. (On the motocross side they dropped all but Weinert, who rewarded them with an Open-Class National Championship). Already KMC was on its way to matching the 1973 budget, and by the end of the season they were over it. It had become a budget cut that never was, and in the final analysis it amounted to no more than a personnel cut.

Now, with Nixon and Carr gone to Suzuki, and Hansen and three of the four tuners also gone, the Ontario Kawasaki contingent consisted of riders DuHamel, Baumann and Wilvert; coordinator Hall and Baumann’s new tuner Jeff Shetler. Tim Smith, who had been racing manager for the motocross team

in 1973, assumed Hansen’s responsibilities, as well, for 1974. But because of his admitted inexperience in road racing (before Daytona Smith had seen only two road races in his life, and they were by accident, at tracks where a motocross was being held simultaneously), he voluntarily remains low-key, which for the most part leaves the show to Hall.

Each person on the team sees the fall of Kawasaki a bit differently. Shetler, the new member, can’t compare it to the previous year but he can compare it to the other teams.

“Aren't our motorcycles horrible?” he asks in frustration. “We have to use all this old stuff from last year,” he continues wistfully, rubbing his fingers over a dented gas tank with the paint scraped off. “Look at the equipment on the Yamaha team. It’s embarrassing to be in the garage next to them.”

“Our bikes are faster than last year,” says Hall defensively, “but only a little bit. Everyone else is a lot faster. But in some ways it’s a better team this year because we're smaller, which makes us more close-knit.”

Few people on the team will agree with Hall’s evaluation of it as being close-knit, but then maybe he's not counting Wilvert. Wilvert, inured to riding on the “B Team”—a term Nixon sardonically attached to his own second-string status last year—is himself stoic about his position; however Wilvert’s tuner George Vukmonovich, whom Wilvert pays out of his own pocket, is more outspoken in his assessment of their deal.

“Randy doesn’t even consider Hurley a part of the team, not even after Daytona when Hurley got 3rd after Randy’s bikes broke,” says Vukmonovich bitterly. “We’ve had to steal and fight for every part we’ve gotten this year. It’s a constant hassle. Hurley has a contract saying he’s entitled to all the same parts as Yvon and Art, but that doesn’t mean anything to Randy.”

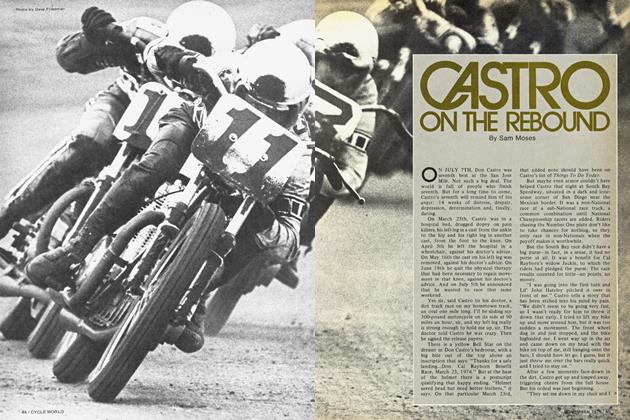

So the team that once owned Ontario was reduced to a bickering, battered, broken also-ran. This year Wilvert rode with his left wrist in a cast, the result of a crash at Talladega; his gallant pain-filled effort netted him a 12th and 9th in the two 100-mile legs, for 9th overall. As at Daytona, his was the only finishing American factory Kawasaki.

Baumann went home before the weekend’s first race. In Friday’s opening practice session he crashed and suffered a concussion, his third of the year. Baumann has crashed no more than •anyone else on the Kawasaki team this season, but his unfortunate habit of landing on his head makes headlines, as well as giving him chronic Blue Devils and creeping gray hair.

All of Kawasaki’s hopes had rested with DuHamel, the sole surviving rider still healthy and in one piece. His H2R should have been so lucky. It was two seconds per lap off the pace in the first heat, which worked out to minus one minute after the 35 laps, in 6th place. The second heat was even worse. DuHamel was holding down 8th when his Kawasaki literally stopped dead⭧. As if it were refusing to continue with the humiliation for one more foot, it locked its rear wheel and threw DuHamel off.

As the Yamahas rolled into Victory Circle and replaced the Kawasakis that had been there last year, Hall was in the Kawasaki garage unbolting the cylinder heads from DuHamel’s engine and peering down the barrels with a flashlight. He wasn’t really sure what he was looking for, but he knew it wouldn’t be horsepower he might find in there. Or money.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

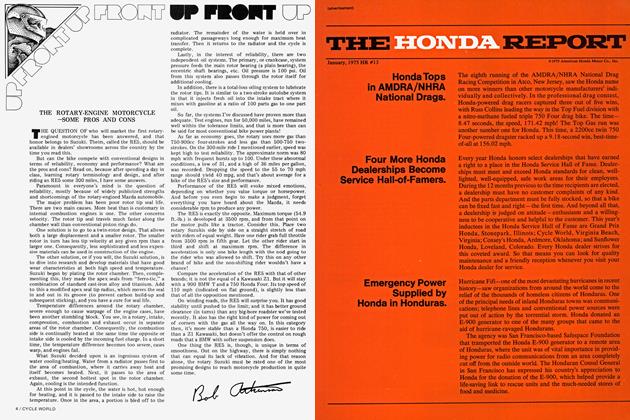

Up FrontThe Rotary-Engine Motorcycle—Some Pros And Cons

January 1975 -

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1975 -

Departments

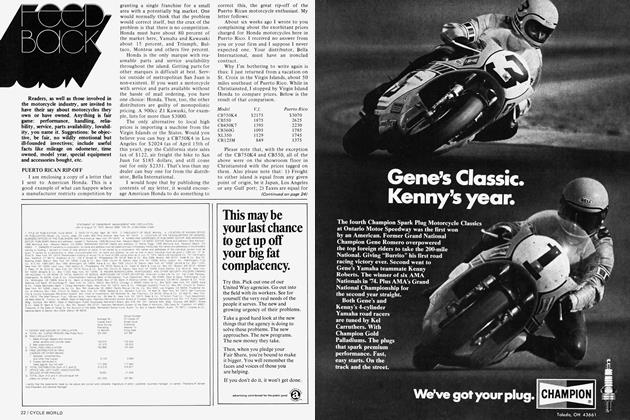

DepartmentsFeed Back

January 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

January 1975 By Joe Parkhurst -

Competition

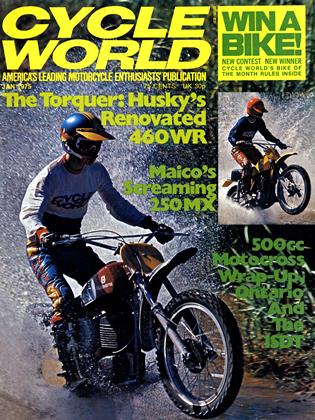

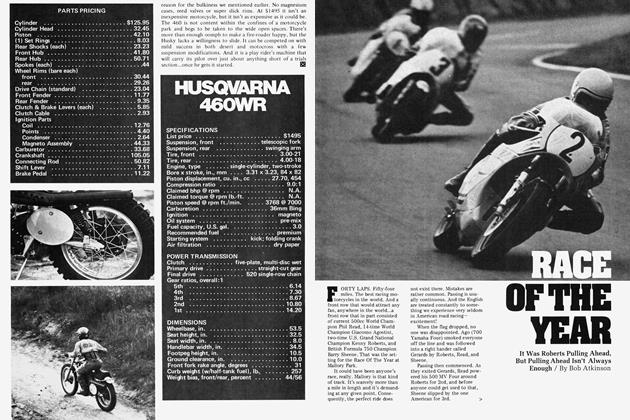

CompetitionRace of the Year

January 1975 By Bob Atkinson -

Competition

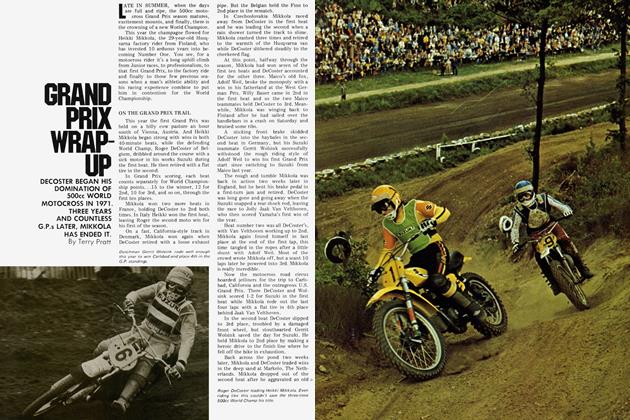

CompetitionGrand Prix Wrap-Up

January 1975 By Terry Pratt